Coaching is confidence. One decision after another, from team formation to practice design to in-game tactical maneuvers, a relentless and rapid express of yes this but not that, if X then Y and not Z, here we stop and there we go. And each of these decisions must be made with boldness and faith in the rightness of that choice—sure, coaches perpetually adjust on the fly, but even those course corrections are not an act of doubt but a demonstration of resolve.

Each successive decision about that which we will do simultaneously requires us to reject that which we will not. “Reject” seems like a harsh word, but in a choppy sea of it depends, unwavering absolutes are a means by which we can project certainty and vision: we never Olympic lift, we never play a zone against that formation, we never train in sand. To inspire trust in those we’re charged to lead, our coaching egos drive us to put a proverbial boot to the throat of each exercise, drill, tool, process, or option we’ve cast away—starving those alternatives of oxygen makes our own choices appear that much more robust.

Starving alternative exercises, tools, and processes of oxygen makes our own choices appear that much more robust, says @CoachsVision. Share on XSo we watch our coaching peers and make sweeping judgments: I may not know everything, but at least I know not to do what THAT Bozo’s doing.

That moment is bracing—a win. We know none of the why, none of the context, nothing about the past-present-future of the athletes involved, nothing but the immediate display of what we’ve deemed useless—and we grind down our boot heel and flex.

Warm-ups, Rituals, and the Lure of Low-Hanging Fruit

Nearly a decade ago, when I began coaching youth soccer and softball, I always knew what was wrong the moment I saw it. Indecision is paralyzing, and without relevant hands-on experience of my own, how else could I move forward absolutely certain that what I was doing was right?

In particular, watching other teams warm up, my judgment was a nail-pointed shiv.

The static stretching circle of players who’ve learned that if they just count to 10 REALLY LOUD during each variation, they won’t have to move a muscle for the next 10 minutes? The straggling jogathon laps around the goal posts before practice? The rote dynamic routine or Tom House arm care exercises, each performed like the obligatory Macarena at your uncool cousin’s way too hot outdoor wedding?

Trash.

As ready as I was to puncture those bloated and wasteful warm-ups, nothing got my blade out faster than watching elementary school-aged softball players come bouncing up to the practice field and, before anything else, be forced to take a knee across from a partner down the right field foul line for the sport’s pervasive, penitent, form throwing warm-up. Kids who’ve sat through a long school day showing up for a sport played out in the dirt, and on minute one, they’re immobilized in the outfield grass, wrist-flicking balls back and forth until allowed to stop and move on.

If I saw your players doing this, in that split second, I knew you didn’t get it. Didn’t get coaching, didn’t get kids, didn’t get athlete development, none of it.

Back in the day, I learned to throw the way you learned to throw—by throwing stuff. I threw rocks at light poles and street signs. I threw pinecones at the trunks and branches of the trees they’d fallen out of. I threw footballs, dodgeballs, tennis balls, baseballs. If something could be crumpled, wadded, and thrown at another kid’s head, I crumpled it, wadded it, and took aim.

When she was four, my older daughter, Riley, invented a game she called “Balls, Balls, the Incredible Balls Game.” This involved taking a bucket with every ball she owned out to the sidewalk—rubber bouncy balls from preschool parties and pizza parlor vending machines, baseballs, racquet balls, whiffle balls, tennis balls, golf balls—and then one after another, she would chuck every ball in the bucket as hard and as far as she could while I tried to catch each on one hop.

During the early stages of my softball coaching career, Deb Hartwig, then a director of coaching for USA Softball and an assistant coach for SDSU, led a half-day coaching course in San Diego in which she eviscerated the knee-down throwing warm-up, shredding the ritual in a merciless comedic diatribe. Validation! I was right all along! Just throw the damn ball!!!

The thing about low-hanging fruit, though, is those qualities—easy, ripe, sweet—are also things that don’t last, says @CoachsVision. Share on XThe static stretching circle, the pre-practice lap, the technique throwing warm-up, these rituals are low-hanging fruit. Dangling right in front of your face, ripe for the picking. Sweet. Grab it, fix it, and make a day-one difference. The thing about low-hanging fruit, though, is those qualities—easy, ripe, sweet—are also things that don’t last.

What Do Agility Ladders Have to Do With Any of This?

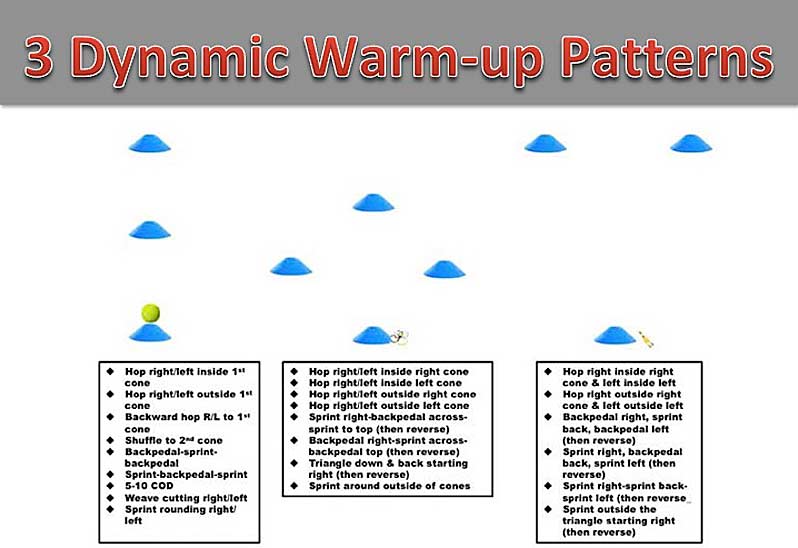

My soccer players don’t jog in practice. No lap around the goal posts, no patterns where the purpose is to accumulate running volume from point A to point B, no box-to-box gassers or suicides. In warm-ups, we focus on the first three steps of acceleration, COD variations, and short relays with and without the ball. We regularly sprint 30s. And for “conditioning,” we play a range of small-sided transition games that involve repeat, sub-max sprints with limited rest between reps.

This is partly a function of scheduling—I have at most two 90-minute practices a week, and jogging is slow and time-consuming. (I encourage my players to jog on their own as a self-directed activity and believe a basic KPI for any player over age 10 is the ability to knock out a 5K without keeling over.)

The absence of jogging is also partly due to my own playing experience. In high school, my varsity practices began with a “grass lap”: a 3/4-mile loop around the entire high school field complex. For capricious and arbitrary reasons, our coach would routinely interrupt each practice with multiple grass laps meted out as a group punishment for failures of execution or attitude—and then we concluded each practice with another 2–3 grass laps for “fitness.”

Every practice began and ended with a punishment, sandwiched around more in the middle.

Not long ago, however, I heard a very accomplished coach refer to the pre-practice laps as one of his most cherished moments in all of soccer. The lads roll out from the locker room, and this is their time—transitioning from the cares of their day to the joy, camaraderie, and demands of the pitch. The athletes run at a pace of their own choosing, banter and bond, and have a known constant before moving on to the ever-changing variations of training.

Same lap, different purpose.

The low-hanging fruit I’ve seized on in the past—what if we replaced that worthless jog with my focused series of hops, jumps, backpedaling, and sprint variations?—may appear obvious based on my own biased perspective, but what if that warm-up lap is serving a legitimate purpose?

I realized that an activity that seemed worthless based on my own biased perspective was actually deliberately applied by that coach and served a legitimate purpose, says @CoachsVision. Share on XSure, some pre-practice field jogs are nothing more than a diversion while a punctuality-challenged coach hurriedly cones off their pitch, just as some static stretching circles have no deeper purpose than being the way they’ve always done it. But those rituals can also be deliberately applied as a focused transition from the individual to the collective, as exercises in self-organization, as a culture-building routine by a coach creating the environment in which they believe their team will thrive.

The dreaded form throwing warm-up? What I used to zealously knife I now regard as something I just prefer not to do. The players I’ve coached through the years have strong, accurate throwing arms, and we come out to the field and let it fly. I also know a large number of players with strong, accurate throwing arms who’ve spent years starting every practice on one knee tossing the ball back and forth.

My starting point is the energy and intent to fire the ball around, and from there we teach and cue how to do that with the proper form and technique. Other coaches choose to begin with the proper form and technique, and from there they teach and cue the energy and intent to do so at game speed.

Different mindset, different tools, different process—same destination.

No, Seriously, What Do Agility Ladders Have to Do With Any of This?

The ladder is one of those ingenious products that can be summed up in two words: portable hopscotch.

Take a group of coaches out to watch kids playing hopscotch on a playground and they’ll pipe in with all the foundational athletic qualities they see being developed: coordination, balance, rhythm, jump and landing variations, proprioception, and the crucial kinesthetic awareness needed in team sports where players must control their bodies in concert with lines, zones, bases, balls, opponents, and other external factors.

Have that same group of coaches watch a 15-second clip of an athlete doing ladder drills on Instagram or Twitter, and it’s an attack-dog frenzy. Because, at some point, someone in marketing decided to call this simple tool a “speed ladder.”

I coach speed, chief…and that ladder, that ain’t it.

Low-hanging fruit. Easy picking. Knowing none of the why, none of the context, nothing about the past-present-future of the athletes involved, nothing but the immediate sight of that which has been deemed useless—post on social media your athletes using an agility ladder and RIP your mentions.

Knowing none of the why, none of the context, nothing but the immediate sight of that which has been deemed useless—post on social media your athletes using an agility ladder and RIP your mentions. Share on XTrue story: seven years ago, after a softball tournament in central San Diego, an agility ladder materialized in my rolling cart with our buckets, balls, nets, and catching gear. Maybe another coach mistook my cart for their own, maybe they’d just seen a viral video of a trainer throwing their ladder in the trash and felt compelled to surreptitiously ditch theirs.

Whatever the case, depending on the age and experience of my players, I now bring that ladder out to the soccer field as often as every 6-8 weeks and as rarely as every six months.

- Higher frequency with young players who are first learning 1v1 skill moves. Just as a player who cannot yet balance on one leg cannot strike a ball with power, a player who cannot adjust their cadence cannot manipulate the ball with a 1v1 move on the dribble. The constraint of the ladder brings players to the front third of their feet and targets their approach to space, both keys to ball skills from sole-rollovers to scissors to stepovers. Moving from ladder patterns without the ball into skill moves on the ball makes a seamless and fun progression for a process that can otherwise feel like “work.”

- Lower frequency with older players, though ladders can be useful during those growth spurts where spatial relationships change and what took five steps a few weeks ago now suddenly takes four. Mostly, though, ladder warm-ups add variety—particularly when combined with mini-hurdles, poles, and other obstacles. High knees, bunny hops, in/out patterns, the Icky Shuffle, 180 and 360 jumps, the players get their heart rates up, apply multiple takeoffs and landings, and do so with enthusiasm and intent.

A useful tool—and no, no one has gotten any faster with it.

Videos 1 & 2. Ladder drills promote the postures and foot positions common with many 1v1 moves in soccer.

With older and elite athletes, Tony Villani at XPE Sports uses ladders as a principal element of his Game Speed method. These are used to train foot placement and change of direction angles to create separation or close space, essential elements of invasion games.

“We always use the ladder, not for footwork or even agility,” Villani explains, “but rather to learn one aspect of change of direction…which is FOOT PLACEMENT.”

Villani describes having a great change of direction as:

- Being able to recognize or anticipate a COD as soon as possible.

- Controlling your speed or being able to decelerate into a controlled speed to COD.

- Then what FOOT PLACEMENT and body position numbers 1 and 2 help create.

- Then a COD can happen. Depending on 1–3, that dictates what best COD can be used.

Video 3. Tony Villani demonstrates how he uses a ladder in four ways to attack COD: 1) Find force to stop; 2) Attack 45; 3) Roll 90; and 4) Sit inside and come down on your inside foot.

The 10-yard down marker is always 10 yards. The bases on a softball field are always 60 feet apart. The 18-yard box is always 18 yards from the goal line. And the ladder’s squares are fixed. Over time, players grow and adapt to how to reach these landmarks. When coaches verbally (or literally) trash ladders…it is like throwing away a perfectly good pancake flipper because it’s not so good for turning over hot dogs on a grill.

Semantics (or, Judging the What Without the Why)

Like many, I commonly refer to “speed ladders” as “agility ladders,” which I know is also a misnomer. No, ladders do not, in fact, train agility—there’s no decision-making or dynamic, reactive component. And while perhaps a cousin to closed COD drills, this tool for “portable hopscotch” is really about developing foot placement, coordination, spatial awareness, and body control.

What you call something only matters if changing the terminology changes the purpose.

What you call something only matters if changing the terminology changes the purpose, says @CoachsVision. Share on XYears ago, I worked with a sports scientist who viewed the term “muscle memory” with the same disdain I held for the form throwing warm-up: please, muscles are bundles of fibers; they have no capacity whatsoever “to remember.” We were talking about the identical phenomenon—consistently repeated movement patterns governed by the central nervous system—but that conversation about outcomes in training went off the rails over a debate between a layman’s shorthand and scientific literalism.

Different tools, same destination.

Yes, words matter…they matter because they are pliable, malleable, and powerful tools for human communication. When we use those tools to jockey for status, when we use them as a shiv, we have ceased to communicate.

Asserting semantic dominance—being the one to body up and impose our will over what a word must mean—flashes temptingly in front of our face; it’s that low-hanging fruit—ripe, easy. There’s no such thing as *mental toughness;* there’s only prepared or not prepared. A *sub-max sprint* is, by definition, not a sprint. *Aerobic base*…do you even know what either of those words means in the first place?

Now we’re not communicating.

Words are not numbers. I can’t say seven to effectively mean six or eight. But if I say agility ladder, and you understand that I mean a tool for portable hopscotch, we don’t need to argue the sports science definition of “agility”: the words have served their purpose. Then, we can rationally discuss whether portable hopscotch is a valuable way to spend ten minutes of practice time or whether perhaps another tool/method could produce an even better result with those same ten minutes.

It doesn’t matter if what you call mental toughness I call resilience and another coach calls grit—we mean the same thing, and what’s important is how we go about developing it with the players we have.

I don’t have to like a warm-up or implement it—I just have to be willing to respect WHY you choose to do it. From there, we are on common ground, says @CoachsVision. Share on XIn my days attacking the form throwing warm-up, one thing I never did was stick around and connect that warm-up to how that coach’s team actually played the game. I don’t have to like it or implement it—I just have to be willing to respect why you’re choosing to do it. From there, we are on common ground.

And when starting on common ground, we can begin to make progress.

Since you’re here…

…we have a small favor to ask. More people are reading SimpliFaster than ever, and each week we bring you compelling content from coaches, sport scientists, and physiotherapists who are devoted to building better athletes. Please take a moment to share the articles on social media, engage the authors with questions and comments below, and link to articles when appropriate if you have a blog or participate on forums of related topics. — SF