Back when I was in college and studying physical education, I learned a lot about the various forms of locomotion and movement patterns and how to use these patterns to develop movement coordination and capacity. One of the movement patterns was backpedaling. Recently, there has been more discussion about backpedaling, but a lot is getting left on the table, so I want to show you where the gold in backpedaling really lies.

There are three areas I would like to cover in this article. The first is how to train backpedaling in the sagittal plane, or in a straight linear process. The second area consists of adding a transverse or rotational component to going and coming out of the backpedal. The third and final area is how we can redirect or change directions from a backpedal into a forward propulsive or acceleration gait.

Sagittal Backpedal Techniques

I’d like to start off by listing many of the areas that backpedaling improves through its unique biomechanical qualities. While doing so, let me share with you the different strategies of using backpedaling. The first two techniques fall under the sagittal, or linear, backpedal methods.

Compact Backpedal

The compact backpedal is most used in the sport of American football, especially by defensive backs. I call these compact backpedals because the athlete compresses the body downward to lower their center of mass and shorten and quicken their stride pattern in order to redirect the body in an instant.

When an athlete uses a compact-style backpedal, where the hips are low and hinged back, the spine pitches forward so the shoulders and head are over the feet, and the knees and ankles are in a very flexed state, the loading for motion is quite different than forward propulsion.

Video 1. A simple way to see efficient backpedaling is by looking at the feet. Observe how the heel cycles behind the athlete.

This position creates a unique communication of the quadriceps with the Achilles-ankle joint complex. You see, as the knees flex, they force themselves to travel sagittal over the toes, and this requires the ankle to also flex a considerable amount. Okay, stay with me here. Because the athlete is moving backward, the uniqueness of how the backpedal gait organizes itself requires the quads to push the front leg knee into extension (not so different from forward acceleration yet), therefore moving the athlete’s body backward.

The difference in forward propulsion and backward propulsion is in the design of the human leg. When moving forward, the shin angle can push down and back while the knee stays in front of the shin based on the direction of travel. Not so in the backpedal…

When the athlete pushes off with the front leg, because the shin points backward at the start, there is actually more of a pulling action until the shin becomes vertical and all the way through the knee extension as the foot travels in front of the body to finish the push off. It is the quads that are highly active in this pull-to-push action during the compact backpedal.

Video 2. Looking from straight on the torso and head give clues to coaches. Focus on how the athlete is able to balance their body as they travel backward.

So why do I say the quads communicate so well with the ankle and Achilles complex? Well, when the back leg—the one moving behind the body in the direction of travel—goes behind the hips, the ball of the foot touches down, forcing a high degree of ankle dorsiflexion as the body rolls over that foot. The quads are very active in eccentrically and somewhat isometrically controlling the flexion of the knee, so the athlete doesn’t collapse their weight down onto the back foot. This interplay of the ankle being so dorsiflexed and the knee being very flexed creates a big support system of the quads and ankle complex working together. The Achilles senses all of this stress and gives valuable feedback to the CNS on how to stabilize this action.

There is a different communication between the muscle and joint complexes with the other style of backpedal. Let me explain.

Extended Backpedal

The second style of backpedal is what I call the extended backpedal. Its name comes from the fact the athlete stands in a tall posture and, therefore, has more extended joints. Although rarely practiced by coaches other than in backward sprinting, the extended backpedal deserves respect for what it can offer the athlete in critical sporting moments.

Although rarely practiced by coaches other than in backward sprinting, the extended backpedal deserves respect for what it can offer the athlete in critical sporting moments, says @leetaft. Share on XFirst, let’s review the mechanics of the extended backpedal.

The athlete starts in a much taller posture, therefore using much longer strides in the gait cycle. Coaches mostly only train this technique as a way to improve posterior chain loading for sprinting, as the action of the hip extension loads the lumbar, glutes, and hamstrings in a unique way. But in reality, athletes often use this tall extended backpedal as a strategy in sporting events.

When an athlete transitions from offense to defense, they immediately change ends of the court or field. If they are one of the first defenders back, they typically take a couple forward acceleration steps to get their momentum started and be in good defensive positioning so the opponent’s fast break doesn’t beat them. Once they know they do not have to sprint to chase the opponent down, they typically perform a 180 and continue moving backward with a tall extended pedal. This strategy allows them to gain valuable information on what their opponents are doing and where they may need to shift their position in order to defend more effectively. Staying tall allows for more speed and keeps their eyesight focused much higher to read the opponent.

Regarding the technique of this tall extended backpedal, there is one very important aspect that athletes must honor to be safe and effective during this backpedal. It is what I call “staying in front of the vertical axis.” So, what does this mean?

Video 3. A natural head is one that looks like it’s part of the entire body and is in concert with the hips. Good mechanics look clean and coordinated, with nothing forced or robotic.

When we backpedal, we do more than just move backward. We rely on our ability to modify our normal running gait mechanics, which is a challenge in and of itself. We create an environment where body awareness and spatial awareness are heightened. And we put our vestibular system on check to keep us oriented in a functional position because we can’t see what’s behind us.

In order to maintain balance while moving, and while possibly accelerating backward, we need to keep our head and shoulders in front of the vertical axis running from the ground up through our body and out to the sky. If we allow our upper body to tilt backward behind this vertical axis line in the direction of the backpedal, we have a difficult time orienting our balance. But if we can keep our head and shoulders slightly in front of the this vertical axis and lead more with our hips—kind of like the compact backpedal does but just not quite as much—we can avoid the feeling of falling backward and maintain our focus on the play in front of us. Also, by keeping our head and shoulders slightly oriented in front of the vertical axis line, we can have better lower body mechanics while striding backward.

When I talk about how the quads and Achilles ankle complex communicate during the compact backpedal, well, the anterior hip and gastrocnemius like to communicate during the taller extended style of backpedal.

If you understand how the knee joint angles affect the activity level of the gastroc’s involvement, you can start to see how the gastroc becomes much more involved in this extended leg style backpedal. On the other end of the leg, and much more proximal, we notice that the anterior hip, or should we say hip flexors, gets placed on a great stretch as the leg moves into hip extension while striding backward. If the hip flexor is being placed on a fairly high stretch because the leg is fairly straight, and there is a fair amount of knee extension upon ground contact, this tells us the gastroc is being stressed to support the stability of the knee along with the hip-quad complex.

From a bottom-up approach, if we have a gastroc muscle lacking flexibility (unable to create adequate dorsiflexion) during foot contact, then the range of motion of the stride will decrease. Additionally, the hip flexors and quads will have not been placed on much stretch, reducing their stability of the knee joint during the ground contact phase.

Regardless of whether the athlete performs a compact or extended-style backpedal, there are always joints and muscle structures that communicate with one another to execute proper mobility and stability.

Training athletes with both compact and extended backpedal styles develops general human movement qualities that will benefit the athlete regardless of sport, says @leetaft. Share on XI guess we could say that training athletes with both styles of backpedal (compact and extended) develops general human movement qualities that will benefit the athlete regardless of sport.

180 Series – Backpedaling with a Rotation

The second approach to backpedal training I like to employ is my “180 Series.” This consists of the transverse or rotational style of challenging body awareness and spatial awareness.

Although I have many exercises based on goals and specific application to the athlete and/or sport, I will share the two cornerstone patterns in the 180 Series.

Forward to Backward

In this first strategy, the athlete begins by slowly running forward (I train these patterns in a submaximal effort to establish efficiency of patterns) for anywhere between 5 and 10 yards. Once they hit this mark, they quickly perform a 180-degree turn in order to continue moving in the same direction, but now with an extended backpedal technique. So, run straight, hit appropriate distance, perform 180, continue backpedaling…

Video 4. A delayed head turn is part of athletic development for all levels. Delaying the head turn isn’t an excuse to move slowly, it’s more about patient timing.

In order to perform this sequence properly and safely, the athlete needs to keep their head and shoulders slightly in front of the vertical axis upon the turn and into the backpedal. I mention this early as a protective strategy against falling backward or losing control. The athlete also needs to be able to quickly rotate the hips and legs so the heel of the contact leg points as close to backward as possible.

I do not want my athletes contacting with the heel pointing 45 degrees away from the backward direction, for example, as this places torque at the Achilles/ankle, knee, and hip. Certainly, I understand this won’t happen perfectly all the time. I just aim for perfection knowing imperfection will have to suffice much of the time.

Video 5. A full 180 is needed in sports, so it’s important to rehearse a rapid change of direction that is fluid and natural. Athletes need to be able to change their body position while moving in the same direction as well.

Another important mechanical factor to consider is the “clearing out” of the front arm to aid in quickly rotating the body. If the arm delays or “blocks,” the thorax isn’t able to rotate effectively, and this then delays the rest of the chain from the hips down to the legs. To clarify: If I run forward and begin my 180-degree turn to the right, my right arm must “swing back” to open my body to the right, and the left arm follows closely behind to push the thorax around. As this occurs, I now have stability via a stretch/tension of the core musculature to quickly turn the hips and lower body around.

In a moment, I will write about how I use early and delayed head turns to manipulate the turning capacity of the body.

Video 6. A quick head turn is vital in situations that demand a play on the ball or on an opponent. An early head turn is not natural for everyone, but many athletes are able to do it with great mechanics.

Backward to Forward

For the second technique of the 180 Series, we begin the athletes with a submaximal backpedal. At the designated distance—again, 5–10 yards usually starts the turning—the athlete quickly turns and begins moving forward with a slow run.

Moving backward and then rotating or turning to transition into forward moving has different possibilities in the sequencing of upper and lower body turning. It has a lot to do with how the head and eyes are positioned and focused. If the athlete quickly turns their head to locate a ball or opponent that has passed them, it is common to see the upper body rotate slightly quicker than the lower body. Conversely, if the athlete’s head and eyes stay focused behind them—let’s say in the case of a softball outfielder or tennis player moving backward yet focusing on a ball that is still in front of them—the lower body tends to open up first, while the upper body lags behind to help keep athletes focused on the ball. Seeing that I’ve opened this can of worms about head and eye position, let’s continue down the rabbit hole.

Video 7. Many cornerbacks or defensive backs are excellent transition athletes. Those that can move backward into a forward run are excellent defenders in other sports as well, including soccer and basketball.

We know athletes’ movements are driven by task and by the environment they are in. When a player must catch a ball, the footwork is simply the vehicle that allows them to accomplish this task. A small out-of-bounds area near the stadium is the environment they must negotiate to accomplish the task. When training the backpedal via these 180 Series exercises, it’s important we change the stimuli, thereby changing the environment and challenging the task differently.

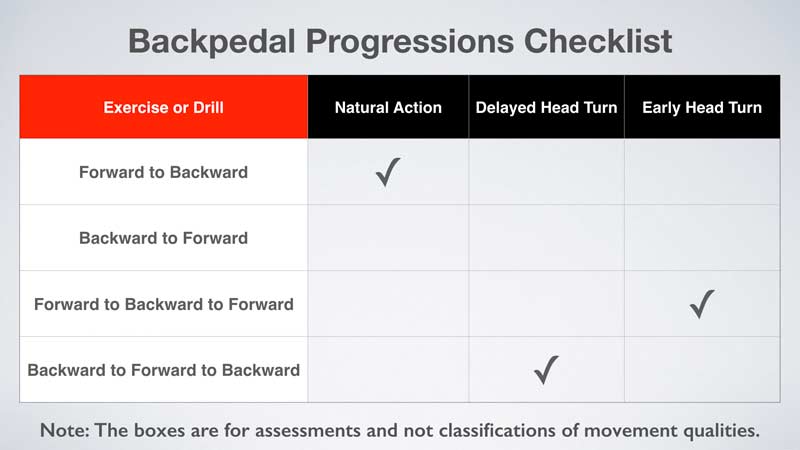

I use a progression to help athletes learn the difference in how the body gets driven to turn more quickly or slowly based on the position of the head and eyes, says @leetaft. Share on XTo do this, I use a progression to allow the athlete to learn the difference in how the body gets driven to turn more quickly or slowly based on the position of the head and eyes. Here is a simple chart with progression ideas.

In this table there are four different possibilities for turning. The first two are what I described earlier: forward to backward and backward to forward running. The second two teach the athlete to negotiate the “unwinding” of the pattern first performed. So, if the athlete performed a forward run to a turn into backpedal, after a few strides they would turn back the same way (this way they undo the 180 rather than complete a 360) and finish the submaximal run with a forward run. Conversely, they could do the backward to forward and then backward again.

The table has four column headings. The first is “Exercise,” which is self-explanatory. The second is “Natural Action,” which means the athlete should perform the exercise without consciously thinking about how to move the head and eyes—just let it happen. We typically see an athlete turn the head and eyes naturally to orient the eyes so they see where they are going.

Video 8. Timing the head motion while backpedaling is sometimes a matter of trial and error. Allow athletes to experiment when necessary.

The third column title, “Delayed Head Turn,” is often called “Delayed Action.” This is when the athlete performs the exercise but keeps the head and eyes focused on the initial direction of travel until they perform a couple steps once the rotation has occurred. For example, the athlete performs a forward run to a backward turn. As the athlete begins to turn the body into the backward run, the head and eyes stay focused where they started, which is straight ahead. Or the athlete could move backward and rotate to a forward run, but they delay turning the head and eyes until they take a couple steps forward—this is common for outfielders, tennis players, and cornerbacks.

The fourth header, “Early Head Turn,” is pretty much what it says—turn the head early in the rotating process of the body, going from forward to backward or vice versa. This typically occurs when an athlete is beat and trying to recover and close on the opponent or ball.

Video 9. The head is the rudder to the body, and fast turns usually encourage a fast motion later. Use early head turns to drive a change of positioning.

The delayed and early head turn methods force a different reaction in the body. The delayed action puts more stress on the cervical and thoracic spine as the lower body attempts to pull the head and spine around. I find athletes with a limited range of motion in the cervical and thoracic spine struggle to disassociate the upper and lower body with this delayed head action, so it’s a great way to assess an athlete.

The early head turn action feels awesome for the athlete, as it virtually “whips” the athlete’s upper and lower body around quickly. As the saying goes, “the body follows the head.” The discovery of balance resulting from staying on a straight path gets challenged during this early head turn strategy. Once again, it’s a great assessment of an athlete’s needs.

Going back to the table above, I randomly placed a check in the boxes. In the early stages, the athlete should allow the natural head turn to take place while performing all the exercises. This builds the patterning of the rotation. But, once comfortable, they can implement the delayed and early head turns to challenge the general development of these head turn patterns with the body rotating. These head turns also be used specifically to help the athlete attain coordination for a sport.

Backpedal Change of Direction

The third approach when teaching backpedal strategies is to challenge mass and momentum control via change of direction. This is an interesting topic, and it tends to light some coaches’ hair on fire. Let’s get after it!

Regardless of whether the athlete performs a compact or extended backpedal technique, they often read the play breakdown in front of them and must quickly get out of the backpedal and begin to accelerate forward. Some examples of change of direction during a backpedal are a pop fly being shorter than originally perceived or a quarterback scrambling and deciding to run instead of pass, which makes the cornerback break out of his backpedal.

The question that always come up—and let me tell you, there are coaches who dig their feet in on why they feel their strategy is best—is should the athlete perform a “vertical heel” plant or a “T-step” plant. The coaches who dig their feet in for one strategy or the other are both wrong.

Video 10. The T-step is, literally, a pivotal movement strategy for athletes. Here from the side, you can see a great view of the back hip in action.

Let’s go back to a statement I made earlier on how athletes make movements based on the task and the environment. They use both perception of what they see and predictability to recall stored patterns that they have used before in similar situations—this is why experienced athletes move more efficiently in certain situations. Okay, hear me out. The athletes are not consciously thinking of the way they want to position their feet during the change of direction from backpedal to forward or angular acceleration. It just occurs based on perception of speed, angles, task, and ability….

An athlete typically uses a vertical heel position, which means they are strictly on the ball of the foot and the heel is straight up, more in a short, quick backpedal distance where there isn’t much mass and momentum to manage. When an athlete has built up higher speeds, and the momentum is great, it is common to see the athlete use a T-step, which is far more stable and safer due to full foot contact and loading of the hip and core to aid in the stability. I always say that the ankle and hip bones turn together to safely load during the T-step.

Video 11. Viewing from the front, the T-step is a clear movement strategy to generate power with the rear leg. A combination of movement work and weight room strength is needed to redirect speed.

The funny thing is that some athletes use a T-step all the time, while others, but not nearly as many, use the vertical heel nearly all the time. My point is that athletes load and unload the moving human system based on their innate control of their own biomechanical system. We can’t put athletes into a box and say; “You can only do this.” It is a mistake to take this approach.

When we get right down to it, managing a backpedal is about controlling angles, says @leetaft. Share on XWhen we get right down to it, managing a backpedal is about controlling angles. We have angles of force application into the ground of the back plant leg. We have angles of the spine and shoulders to control the orientation of posture going in and coming out of the plant. And we have angles of acceleration once we come out of the backpedal break.

The footwork we use is not always a teachable skill, but rather a reaction to the body’s kinesthetic reaction to the moment. This is very important to understand so we don’t train something that isn’t trainable. I don’t mean that we can’t train some of this. I have seen football coaches train cornerbacks by only allowing them to use the vertical heel concept in their controlled drills during practice, yet on game day these same cornerbacks instantly use a T-step to break out of the backpedal to make a play.

Video 12. The final video shows the differences between stepping back and planting a T-step. Notice the difference between a quick backward step and opening up the hip for power.

When coaches don’t understand the interplay of task, biomechanics, range of motion restrictions, strength and elastic capacities of an athlete, and a host of other variables, it forces them to dig their heels into the ground with unfounded information.

What we can teach and emphasize to our athletes during the backpedal is setup, posture, position, and the mechanics of the arm and leg, based on the style of backpedal being used. The backpedal isn’t a skill that most athletes use for long intervals during a single play, but it might mean the difference for being successful throughout the competition.

The backpedal isn’t a skill that most athletes use for long intervals during a single play, but it might mean the difference for being successful throughout the competition, says @leetaft. Share on XA Strategy for Training and Competing

It’s important to realize that the development of the backpedal isn’t so linear. There are many factors we must consider when building a stable backpedal pattern through various postures and drivers. An example of a driver is the rotational patterns just described in the 180 Series, along with delayed and early head turns. Backpedaling is a strategy to help athletes compete better in their sport, but also a training strategy to bring about various levels of coordination, mobility, stability, and general movement qualities.

I hope this article and the backpedal strategies within it give you a different view on utilizing backpedal training to improve the performance of your athletes.

Since you’re here…

…we have a small favor to ask. More people are reading SimpliFaster than ever, and each week we bring you compelling content from coaches, sport scientists, and physiotherapists who are devoted to building better athletes. Please take a moment to share the articles on social media, engage the authors with questions and comments below, and link to articles when appropriate if you have a blog or participate on forums of related topics. — SF