Speed kills.

As coaches, we have often heard and used this phrase—and for good reason. Speed is a critical factor in team sports: whether it’s outrunning angles on a football field, winning a 50-50 ball on the soccer pitch, or recovering possession in basketball, speed consistently proves to be a decisive advantage. Many coaches preach the value of speed, and athletes strive to improve it. The fundamental approach to speed training seems straightforward: run fast and do it often. Many athletes and coaches encounter a common roadblock, however—progress stagnates and the expected speed improvements plateau.

At this juncture, coaches can be temped to turn to various adjustments. Should we add more volume? More intensity? Or should we shift focus entirely? The answer, I believe, is rooted in a fundamental principle: precise, intentional, and consistent speed development must be the unwavering priority.

Sports are won and lost with speed—I’m in my 11th year of coaching (working primarily with college and high school athletes), and I have yet to see a slow and sluggish athlete thrive. Speed can provide a distinct advantage in team sports, especially at the high school level. Here at Madison-Ridgeland Academy (MRA), we are blessed with great kids who have a tremendous work ethic and are highly competitive, almost to a fault sometimes. What we are not blessed with—especially on the football field—is size. We are often outmatched physically. So, the question I had to ask myself was “How can we provide an X-Factor for our athletes?” And, I landed on making our system a speed-based program.

When programming for any of our teams, male or female, speed is in the forethought of my process. Does this make us faster? If the answer is “No,” I figure out a better way. Does that mean we neglect strength? Simply put, “No.” Strength is a pillar of our program—but the frame that we operate out of is that strength training is aiding us in our speed development.

When programming for any of our teams, male or female, speed is in the forethought of my process. Does this make us faster? If the answer is “No,” I figure out a better way, says @Coach_GAdams. Share on XBreaking the Cycle of Inconsistency

Despite the desire for faster and more explosive athletes, many coaches fail to treat speed as the core focus of their training regimen. Speed work is often neglected during the in-season phase or undermined during the off-season by the overuse of long, slow conditioning drills that do little to nurture explosiveness.

If we are serious about improving speed, we need to break the cycle of inconsistency.

The first hurdle is making speed the cornerstone of our training philosophy. We need to approach every aspect of preparation—from practices to conditioning—through the lens of speed development. This requires a shift in mindset for most coaches. Speed must be ingrained as a core identity of the entire program, rather than treated as a temporary priority or an afterthought. Establishing this unwavering focus is essential for achieving transformative results.

Despite wanting faster & more explosive athletes, many coaches fail to treat speed as their core training focus. Speed work is often neglected in-season or undermined in the off-season by the overuse of long, slow conditioning. Share on XOnce we have made this paradigm shift, now we start chasing performance. When we can focus on the right things, speed improvements can come quickly. The puzzle, however, gets harder when those improvements start to plateau. Where do we go from here? How do we get the speed numbers to start improving again?

One of the most common pitfalls in speed training is the tendency to focus on volume rather than quality. When I first started, I believed that if we sprinted more often and worked harder, we would outlast the other team. However, when I evaluated the intent behind the work, I realized these “sprints” were often performed with submaximal effort, essentially turning them into fast jogs. By definition, that isn’t true sprinting—instead of gaining the speed advantage we were striving for, we were actually achieving the opposite.

This realization led me to reevaluate how we were programming our speed training. The belief that more is better often leads athletes and coaches to increase the number of sprints or conditioning drills, assuming that more repetitions will automatically lead to faster performance. However, speed is a skill that thrives on intensity and precision, not sheer volume. The misunderstanding here is rooted in the idea that endurance and speed can be trained the same way—but in reality, they require very different approaches.

In contrast to volume-based training, speed development thrives on short, high-quality efforts. To truly enhance speed, an athlete needs to perform sprints at maximum velocity, with full effort, and with complete recovery between each repetition. This ensures that each sprint is of the highest possible quality and trains the body to operate at peak efficiency. Speed training heavily taxes the central nervous system because it involves maximal or near-maximal efforts.

To truly enhance speed, an athlete needs to perform sprints at maximum velocity, with full effort, and with complete recovery between each repetition, says @Coach_GAdams. Share on XUnlike aerobic or endurance work, where fatigue builds gradually, speed training requires immediate and explosive outputs, which engage fast-twitch muscle fibers and heavily stress the nervous system. These maximal outputs demand significant energy and create a high level of neuromuscular fatigue, which takes time to repair. Inadequate recovery can lead to chronic fatigue, slower sprint times, and the inability to maintain proper technique during high-speed efforts. Over time, this creates a vicious cycle where athletes are no longer training at their peak, reinforcing poor movement patterns and limiting overall speed potential.

Maximal effort speed training is essential for developing explosive sprint ability on the field, such as chasing down a ball, breaking away from defenders, or closing space on an opponent. These efforts typically last 5 to 10 seconds and require rest periods at a 1:10 to 1:20 ratio to maximize recovery and ensure high effort performance. For example, after a 10-second sprint, the athlete would rest for a minimum 100 to 200 seconds. This allows them to maintain proper sprint mechanics and exert maximal effort on each repetition, which is crucial for enhancing pure speed and game-changing explosiveness.

Speed is not just about raw athleticism; it’s about proper mechanics that ensure every ounce of energy is used effectively. Developing good sprint mechanics is crucial because the slightest inefficiency can cost valuable time and energy, especially when an athlete is fatigued.

Resisted Sprints & Best Practices with High School Athletes

Another solution I use to break through these plateaus is implementing various types of resisted sprinting. Resisted sprints are a highly effective tool for improving speed, acceleration, and power. These methods are often used to enhance an athlete’s ability to generate force, improve sprint mechanics, and develop explosiveness—all of which are critical components of speed. Resisted sprints involve adding external resistance, such as a sled, prowler, or band, to the athlete’s sprint.

The primary benefit of resisted sprints is the improvement in an athlete’s ability to generate force. When an athlete sprints with resistance, such as pulling a sled, their muscles must work harder to overcome the additional load. This increased demand trains the neuromuscular system to apply greater force during the sprint, particularly during the acceleration phase. The increased force production translates directly to unweighted sprints, where the athlete will be able to push harder and generate more power off the ground. In sprinting, force application is everything. The faster and harder an athlete can push off the ground, the faster they will accelerate. Resisted sprints strengthen the key muscles involved in sprinting, such as the glutes, hamstrings, and quads, making it easier to reach top speed faster.

In sprinting, force application is everything. The faster and harder an athlete can push off the ground, the faster they will accelerate, says @Coach_GAdams. Share on XResisted sprints are particularly effective for improving the acceleration phase of sprinting, which covers the first 10-30 yards. This phase requires the athlete to lean forward and generate significant horizontal force to build speed from a stationary or slow-moving position. Resisted sprint training forces the athlete to maintain an aggressive forward lean while driving their legs with more intensity to overcome resistance. In team sports, the ability to accelerate quickly can make the difference between getting to the ball first, making a defensive play, or winning a race. Athletes who improve their acceleration can close gaps faster, react quicker, and gain a competitive edge.

Resisted sprints also serve as a valuable tool for refining sprint mechanics, especially during acceleration. With resistance, athletes must focus on driving their knees forward, maintaining proper body angles, and extending their hips for maximal power. The added resistance forces athletes to stay in the proper acceleration posture longer, helping them reinforce good technique. Good sprint mechanics are crucial for reducing wasted energy and improving running efficiency. Resisted sprints force athletes to focus on their form while under pressure, which helps transfer these mechanics into regular, unweighted sprints. Athletes who maintain proper form are more likely to avoid injuries and improve their top-end speed.

Best Practices for Resisted Sprints

- Gradual Progression: Start with light-to-moderate resistance and gradually increase the load as the athlete’s strength and mechanics improve. Too much resistance too soon can alter running mechanics and reduce the effectiveness of the drill.

- Focus on Form: The goal is to enhance sprint mechanics, so athletes must maintain proper form while sprinting with resistance. Excessive resistance that causes athletes to “grind” through each step will do more harm than good. Athletes should still be sprinting, not struggling through the movement.

- Monitor Distances: Resisted sprints are most effective for short distances, particularly the acceleration phase (10-30 yards). Sprinting with resistance over longer distances can lead to form breakdowns and inefficient movement patterns.

- Incorporate Unresisted Sprints: Always pair resisted sprints with unresisted sprints in the same session. This helps athletes transfer the strength and power gains from the resisted sprints into regular sprinting form, enhancing overall speed development.

The Importance of Timing & Tracking

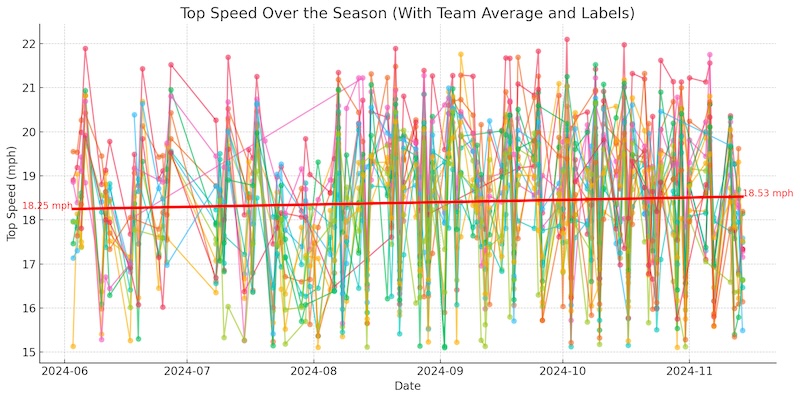

Lastly, you have to track the data. I don’t care what implements you are using (timing gates, GPS, video analysis, stopwatch, etc.), but the numbers have to be monitored consistently. One of the most important tools and insights we have is the ability to track sprint times. Monitoring sprint times throughout the year provides invaluable insights into an athlete’s performance and progression. By consistently measuring sprint times, coaches and athletes can monitor speed development, identify trends, and address weaknesses that may be holding back overall performance.

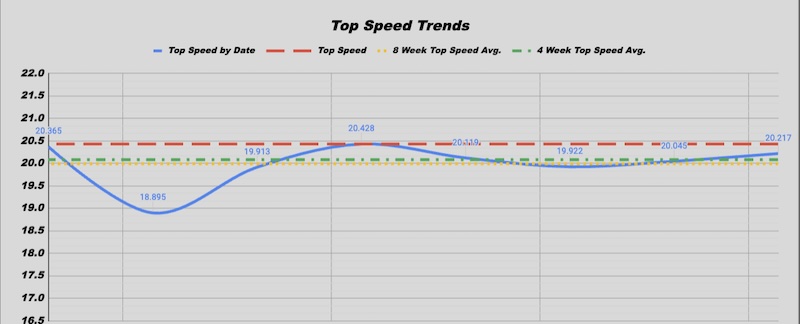

I focus on a few key metrics across all sports to optimize performance. Each week, we test a Fly 10 using both a 5-yard and a 20-yard lead-in. These times help us calculate a rolling average to monitor performance trends and provide athletes with regular opportunities to reset their personal bests. Ideally, athletes should match or surpass their personal bests at least once every four weeks.

Video 1. Running timed sprints.

Tracking these metrics serves two purposes: it encourages athletes to consistently strive for high performance and facilitates important conversations when times begin to decline. For instance, if an athlete’s performance drops, it can signal the need to address readiness, recovery, or potential injuries.

In addition to the Fly 10, we use GPS tracking to measure maximum speeds (MPH) in field sports, providing valuable insights into practice and game demands. Combining the Fly 10 data with GPS metrics allows us to align training with the physical demands of competition. We ensure athletes regularly reach max velocities during the week to condition their tissues and prepare them for the high-speed demands they may face in games. Together, these tools help us train effectively and ensure our athletes are ready to perform at their best on game day.

In team sports, where speed can be the deciding factor in key moments, regularly tracking sprint performance offers several crucial benefits. Tracking sprint times allows you to gauge an athlete’s speed development over time. By comparing sprint times from the start of the season to mid-season and the off-season, I can see whether the training program is yielding the intended results or if adjustments are needed.

Progress is not always linear. Speed training is different from strength training. It is not linear and can’t be. There are many variables and factors that play a role in good speed training sessions, MPH readings, or timed sprints. It is not as simple as “add a 5.” If that was the case, there would be no need for this article, we would all just preach “run faster than you did last week.” Sprint times provide objective data that shows whether an athlete is getting faster or if their performance is stagnating. This allows us to adjust the training focus—whether adding more intensity, focusing on mechanics, or addressing recovery needs.

By comparing sprint times from the start of the season to mid-season and the off-season, I can see whether the training program is yielding the intended results or if adjustments are needed, says @Coach_GAdams Share on X

Another benefit of tracking sprint times is that they can be a reliable indicator of an athlete’s freshness or fatigue levels. A sudden decline in sprint performance could signal overtraining, excessive volume, or inadequate recovery. By tracking times, you can spot early signs of fatigue that might lead to burnout or injury if left unchecked. In team sports, where players often face demanding schedules, knowing when an athlete’s speed is declining can prevent injuries. If I’m noticing a drop in sprint times over several weeks, it may be time to taper the athlete’s workload, adjust recovery protocols, or focus more on speed maintenance rather than volume-heavy conditioning.

Tracking sprint times over various distances is a powerful tool for breaking speed plateaus by identifying specific weak points in an athlete’s sprinting ability. For example, an athlete may excel in the acceleration phase (0-10 yards) but struggle to maintain top-end speed (20-40 yards). These insights allow you to break down the sprinting process and profile athletes based on their individual needs.

In team sports like soccer and football, the demands for sprinting vary—whether it’s quick bursts off the line, sustained sprints down the field, or rapid deceleration. By analyzing split times at different distances, you can pinpoint where an athlete is hitting a plateau and target specific aspects of their sprinting. Whether it’s refining acceleration mechanics, improving speed endurance, or enhancing change of direction, addressing these weak points with focused training allows athletes to break through performance barriers.

This targeted approach not only optimizes an athlete’s sprinting ability but ensures that training is aligned with the unique demands of their sport, leading to more comprehensive and sustained speed development.

Using speed training metrics like Fly 10 times to inform strength training involves identifying specific performance deficiencies—such as maximal velocity, acceleration, or force production—and tailoring programming to address them. For velocity-deficient athletes, who excel in short bursts but struggle to maintain or improve top-end speed, the focus should be on explosive and plyometric exercises (e.g., bounding, skips, or barbell jump squats), Olympic lift derivatives, and sprint-specific work with minimal emphasis on heavy, slow lifts. Force-deficient athletes, who lack power in acceleration or low-velocity movements, benefit from foundational strength exercises (e.g., squats, deadlifts), power-based movements like trap-bar jumps and heavy sled sprints, and plyometric drills such as depth or loaded jumps.

By analyzing metrics such as flying sprint times, split data trends, and force-velocity profiles, you can determine whether an athlete’s deficiency lies in velocity or force production. Adjusting the strength program accordingly ensures targeted improvements—velocity-deficient athletes emphasize rate of force development (RFD) and elasticity, while force-deficient athletes focus on building strength and applying force effectively. Resisted and assisted sprint variations complement both profiles, enhancing specific adaptations for speed and power development.

Another factor that is difficult to quantify—but is invaluable—is creating competition. Consistently tracking sprint times can be a great motivator for athletes. Knowing that their progress is being measured fosters a competitive environment, both within the team and for personal goals. Athletes can compare their current times to past performances or to teammates, fueling a drive to improve.

Furthermore, posting sprint times publicly or using leaderboards can foster team camaraderie and push athletes to strive for faster times, knowing they are being measured and compared in a way that reflects directly on game-day performance.

One of the key benefits of tracking sprint times is that it allows you to evaluate the effectiveness of specific training interventions. If you introduce a new speed training drill, implement resisted sprints, or adjust conditioning volumes, tracking sprint times can reveal whether these changes are having the desired effect. Objective feedback from sprint times helps you determine which training methods are working and which aren’t. If a new technique or program leads to better sprint times, you know you’re on the right track. Conversely, if sprint times stagnate or decline after introducing a certain drill or conditioning block, you can quickly adjust the program before it negatively impacts performance.

For example, if you implement resisted sprints to improve acceleration but don’t see faster 20-30 yards times after a few weeks, you might need to adjust the resistance load or revisit sprint mechanics drills to address the underlying issue. Sprint times offer real-time feedback to guide these decisions.

Where We’ve Been and Where We’re Going

Over the years, I’ve witnessed the transformative power of a speed-first approach in athlete development. Speed is the great equalizer in sports—regardless of size or strength, the ability to accelerate, maintain top-end velocity, and change direction quickly can define success. Watching athletes consistently set personal records and shave time off their Fly 10s throughout the season has been one of the most rewarding aspects of my coaching journey. These improvements are not just numbers on a stopwatch; they represent hours of hard work, focus, and the willingness to embrace a process rooted in precision and intentionality.

More importantly, these gains have a ripple effect on the athletes’ mindset. As their speed improves, so does their confidence and competitiveness. It’s one thing to tell an athlete they’re getting faster, but when they feel it—when they start beating their opponents to the ball, breaking away from defenders, or recovering to make game-changing plays—it changes the way they approach not just their sport, but their development as a whole. They become more engaged, more determined, and more willing to push their limits. For me as a coach, these moments are what make the process so fulfilling. Speed is more than a metric—it’s a catalyst for growth, both on and off the field.

Speed is more than a metric—it’s a catalyst for growth, both on and off the field, says @Coach_GAdams Share on XOne moment that stands out is when a player who initially struggled with acceleration managed to cut nearly two-tenths of a second off their Fly 10 time after targeted interventions. It wasn’t just the time improvement that impressed me—it was the athlete’s newfound belief in their ability to compete and excel. These moments reaffirm the importance of addressing individual needs and tailoring our methods to maximize every athlete’s potential.

Building on this success, we’re developing a comprehensive system to profile athletes based on their specific deficiencies. Whether it’s insufficient force production, a lack of explosive acceleration, or difficulty sustaining top-end speed, this profiling system will enable us to design precise, individualized training plans. By integrating advanced tools like force-velocity profiling and GPS tracking, we’re gaining a deeper understanding of each athlete’s unique strengths and areas for growth.

This personalized approach does more than improve PRs or sprint times—it fosters a culture of accountability, growth, and excellence. Athletes aren’t just running faster; they’re learning to push their limits, embrace challenges, and set higher goals. As a coach, there’s nothing more fulfilling than seeing these lessons extend beyond the field, shaping their mindset for success in all aspects of life.

Looking ahead, our focus is clear: refine the profiling system, continue leveraging data to guide our training, and ensure that every athlete feels empowered to break through barriers. By staying committed to innovation and athlete-centered coaching, we’re not just building faster athletes—we’re building resilient, driven individuals ready to excel in competition and beyond.

Since you’re here…

…we have a small favor to ask. More people are reading SimpliFaster than ever, and each week we bring you compelling content from coaches, sport scientists, and physiotherapists who are devoted to building better athletes. Please take a moment to share the articles on social media, engage the authors with questions and comments below, and link to articles when appropriate if you have a blog or participate on forums of related topics. — SF