[mashshare]

If asked to describe a prototypical receiver, coaches will cite traits like speed, size, hand-eye coordination, foot speed, agility, and jumping ability. We essentially describe Julio Jones. The issue coaches all encounter is what to do when they aren’t blessed with a stable of Julios on their roster. The natural first step is to prioritize skills and play the kid who possesses the most crucial skills for the position.

For years, coaches, particularly at the high school level, have looked to their fastest athletes with decent hand-eye coordination to play wide receiver (WR). This seems to be common sense, as a coach should want their fastest kids on the perimeter to stretch defenses vertically and horizontally. But coach long enough and the inevitable question arises: Why can’t the all-conference track kid separate on the field?

I am a firm believer that the issue lies with traditional receiver development. Too often, coaches subscribe to the belief that many of those essential skills are fixed traits. We fail to develop the skills critical to be elite receivers.

Too often, coaches subscribe to the belief that many essential skills are fixed traits. We fail to develop the skills critical to be elite receivers, says @WLCCoachTreske. Share on XThis is more evident at each higher level of football. As the competition level rises, the margin for error becomes thinner. Players must master skills other than speed and hand-eye coordination. As coaches, we must then ask what skill(s) most drastically separates the good from the great receivers, and how do we develop that skill? The answer, like most answers in football and athletics, lies in the film.

Going Beyond Speed

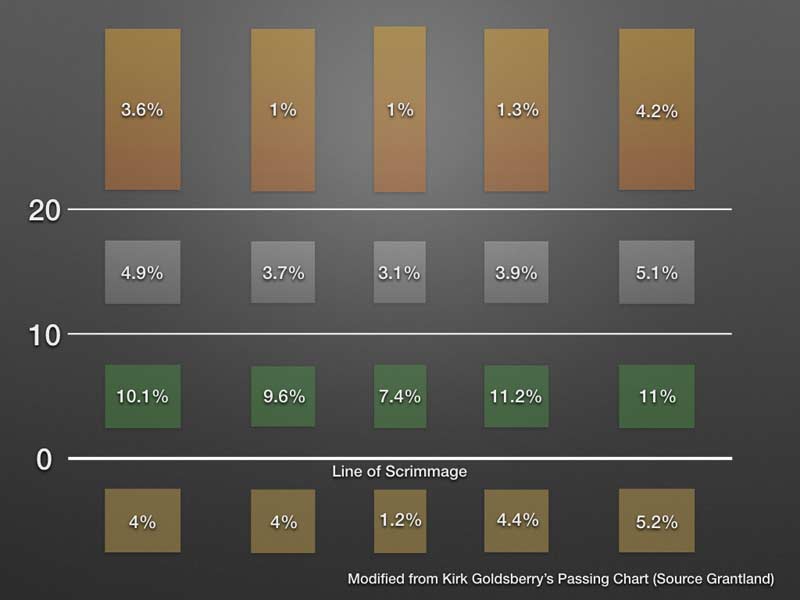

If you analyze the film, the answer is not speed, it is movement efficiency. In fact, as the level of competition rises, the difference in speed is often minuscule. For example, in the 2013 NFL draft, the difference between the 10-yard times for the No. 1 and No. 100 WR prospects was .04. In fact, if you went through the top 100 prospects, you’d see a range of 1.5–1.61 seconds on their first 10 yards. This minor disparity carries over into the 20-yard times as well. If your passing offense is anything like ours—or any of the NFL teams, for that matter—that means that the speed difference is subtle in nearly 90% of your throws.

This limited speed disparity is not unique to the NFL and D1 programs; it is found at all levels of football. Our team, for example, just performed initial off-season testing, and the difference between our fastest wideout and our slowest was .15 seconds. In fact, we’ve had several of our team’s top receivers in the middle of the pack. Though any subtle difference is an advantage, this limited range in times suggests it’s something more than speed that results in on-field production—it’s movement efficiency and technique.

This limited range in times suggests it’s something more than speed that results in on-field production—it’s movement efficiency and technique, says @WLCCoachTreske. Share on XI have been fortunate to work with some great WR coaches, and we’ve discussed and debated the subtleties of stance, stem, demeanor, leverage, release techniques, and catch point and their impact on WR development. All of these techniques are critical factors in becoming a complete WR, but in my experience, the film suggests that the X factor in performance is efficient breakpoint mechanics. The ability to decelerate into a break and reaccelerate out of a break is what divides the best receivers from the rest. The beauty is that this is a skill that can be learned and trained over time.

Breakpoint Mechanics

To develop breakpoint mechanics, we need our athletes to understand the ideal body position they must be in to change directions. In our program, we call this our “stick” position, since it serves as both a term and coaching cue to reinforce the need for the athlete to apply force (“stick” his foot) into the ground. This position is foundational in movement mechanics.

1. The ‘Stick’ position.

Coaching Cues: Shoulder over knee and ankle, neutral core, hips dropped, sprint action in arms, weight loaded on lead leg, drive through ball of foot.

By getting into the stick position and loading the lead leg, we give ourselves the ability to drive out of our break explosively at almost any angle. The impact of this is tremendous; if you master the stick, you can master any route in your offense. We teach this position, much like you’d teach any body movement, through a progression series.

‘Stick’ Progression

We begin by positioning the athletes along a line in their WR stance with their inside foot forward. We then demonstrate and describe the cues of the position and then cue them to get into a stick position. Check and correct the athletes as they hold the stick position, then rep the movement repeatedly on each side—occasionally asking them to hold and control the movement. Like all movements, repetition is crucial. Once they master the baseline position, we work using a triphasic approach to teach and strengthen the position.

Three Phases of the Break (and all movements)

- Eccentric – Have athletes slowly descend (3–5 seconds) into the bottom portion of the movement.

- Isometric – Have athletes quickly drop into the bottom portion of the movement and hold the bottom position (3–5 second hold).

- Concentric – Have athletes quickly execute the movement and drive out explosively (we use jumps and sprints out of the position).

Once the athletes begin to execute from a stationary position, we have them walk the position out and stick on every third step. We gradually progress the tempo to 50%, 75%, and full speed between the stick step, always asking them to perform an isometric freeze and control the stick movement early on. Control is the key. Once we master the stick, we then teach them how to transfer and drive out of the position for the variety of routes we’ll run. We categorize routes into four categories by their angle of departure.

On the field, we rep all four of our techniques in a progression:

- Stationary breaks

- Controlled tempo breaks (walking, 50, 75, 100% with controlled holds)

- Cone drills with multiple reps for breaks (also with tempo—can be creative with patterns)

- Full routes

Three Essential Breakpoint Techniques

1. Stick and Snap

Route Examples: Hitch, Curl, Comeback, Fade Stop, Perimeter Screens

This is one of the more challenging breakpoints, as athletes need to transition their body in almost the opposite direction. This requires precise technique on the upper and lower platforms, square shoulders, and eccentric strength to drop-sink the hips in position. We emphasize snapping the shoulders at the defender and staying square until AFTER the athlete drops his hips.

2. Stick and Roll

Route Examples: Speed Out, Deep Out, Speed Dig

This set of routes is the most varied in the way they are taught. Regardless of whether you teach a speed cut/square out, two-step, or four-step, the principle of the break is the same. We aim to have the athlete sink the hip and roll off the instep of the plant foot. Arm drive is key to rip to the outside explosively. In addition, teaching the athlete to turn their head out of the break is crucial to locate the ball.

We see two common mistakes on this one:

- Athletes do not lead the shoulder over the hip and ankle and get overextended.

- Athletes drag their opposite foot, which slows them down or causes a false step.

3. Stick and Lean

Route Examples: Slant, Post, Corner, Post Corner

This is the probably the most natural and most common breakpoint we see. Athletes execute the stick position with a slight outstep and shoulder lean opposite the break to: 1) load the outside leg to drive laterally; and 2) influence or “freeze” the defender opposite the break. The shoulder MUST follow the hip and ankle, or the athlete will false step (this is a common fault).

Progressing the Breakpoint

To challenge your athletes and help take the break mechanics to another level, there are a variety of tools and methods you can utilize, both on the field and in the weight room. In our program, we use three primary tools (bands, boxes, and medicine balls) and look to combine/progress them with this framework in mind: The athlete needs to be able to control the vertical force to stop before we focus on the rotational force required to transition horizontally.

Here is our foundational breakpoint progression:

1. Banded Stick

This an extension of our base stick drill, using the band as both resistance and sensory feedback. If the athlete does not drop the hips or keep the shoulders down, the band will pull back. We will also place the band laterally to work on getting an explosive drive out of the break.

2. Box Drop Progression

We use an elevated surface as a means to add resistance. The higher the box, the more force athletes are required to control. From the box, we work on dropping to a stick, sticking and popping off the floor, and ultimately sticking into our different route families.

3. Med Ball Rotation (from Stick)

Getting out of the stick position requires a strong push step and explosive rotational force. We love using med balls as a way to work the rotation. We begin with athletes in the stick position and work rotational throws into each route family. We then progress to catching the ball into a transition from different angles and then finally catching it mid-stick into the families.

4. Banded Stick Plus Med Ball Rotation

We now combine the two methods to work additional resistance. The combinations work from the easiest route families (stick and lean) and catch points (directly in front) to the more challenging positions.

5. Box Drop Plus Med Ball Rotation

The final combination of these methods and tools is dropping from the box to a med ball rotation/break. Like the other med ball methods, we add tosses from progressively varying positions to make it more difficult.

Taking It to the Next Level: Decelerating

Learning to break is the first step, and it will help your receivers be explosive in their routes, particularly the quick game. After we teach the essential breakpoints, we feel the next level is to teach our athletes how to get into those breaks at deeper levels by teaching deceleration mechanics.

There’s a wide variety of factors that go into being able to decelerate quickly (ankle, hip mobility, hip/glute stability, quad/core strength, etc.), but we try to break it down to three critical elements for our athletes to focus on:

- Remaining as level as possible in the route stem (showing vertical).

- Keeping shoulders over knees on toes to get to a stick position.

- Pushing down as hard as possible (feet, hips, and arms).

Key Drill: Drums to Stick

Route Examples: Curl, Comeback – Can also use for Dig or Deep Squared Out.

This is the most challenging breakpoint, as we need to transition our body in almost the opposite direction at depths of 10–15+ yards. We describe these as level 2 routes, and this technique is essential for them, especially curl and comeback variations. The nature of these routes requires us to decelerate using what my friend Brandon White calls “the drums technique,” to throttle down and decelerate to execute our stick technique.

To teach the drums, we use a completely new progression emphasizing arm drive, foot fire, and hip level to decelerate. To gain separation, our goal is to use this technique to throttle down in just 2–3 steps. This progression is critical to master as it must eventually lead us back into the foundational stick position to be efficient and explosive.

We use the following drill progression to improve our drums to stick:

1. Banded Stem

We use a partner to hold a band fixed around the WR’s waist to emphasize remaining level with shoulders over knees and toes. We will work all five stems we teach (vertical, inside, outside, radical inside, and radical outside).

2. Marching Drill Progression

This drill is the drums technique in action. Working on dropping our hips and breaking routes in three steps, we coach our athletes to push down as hard as possible as they march down the field. Many receivers will want to reach, so pausing on the final step is key to check if they get to the stick position. We use a band as a tool by holding it behind or from the side to cue the athlete to push their hips down to stabilize.

3. Angle Marching Drill

This is a progression of the marching drill that helps the athlete work on pushing hard and opening the hips out of the drums. We will progress our tempo and go from paused breaks to rapid fire.

4. Banded Drums Into Break

Now that we can better control force into our break, we work the break from our drums position with a band. The band forces us to learn to control our body by dropping and stabilizing with our hips, and it helps us really work an explosive drive out of our deceleration.

5. Cliff Drill Progression

This is a sprint to stick at a fixed point on the field. We like to use a line on the field as our imaginary “cliff” that the athlete can’t go over. We progress from 8–15 yards, depending on where the athletes are. We can add a band as well for athletes who are rising up or for athletes who need more resistance to challenge them. Once we have shown our technique is solid, we can also execute on a visual cue (coach drops or turns hips, etc.). This helps us work the read routes we use, such as a vertical or curl option.

The final progression of the cliff we use is a partner race to the football. We can do it where one partner is just beyond the top of the route, or we can have both partners work the route and break to a catch point.

Moving Forward

The wide receiver position is a position that is often under-coached, and because of this, we see dramatic results after working with athletes for only a few hours in our indy segments or at the summer camps we work with. To play at a high level, these athletes are required to possess a wide skill set, attention to detail, and incredible precision. What I hope excites you as much as it excites me is that all of these attributes can be developed and coached over time. The key to developing the fundamentals of movement is often stepping back and focusing on the basic elements to progress. Even speed, the elusive holy grail in sports, can be developed with proper coaching and programming.

The wide receiver position is often under-coached, and because of this, we see dramatic results after working with athletes for only a few hours, says @WLCCoachTreske. Share on XKeep working and good luck this season! Thank you for this opportunity to share a little of what we do to develop our wide receivers. Please contact me at [email protected] if you or anyone on your staff has additional questions or would like to discuss wide receiver development further.

Since you’re here…

…we have a small favor to ask. More people are reading SimpliFaster than ever, and each week we bring you compelling content from coaches, sport scientists, and physiotherapists who are devoted to building better athletes. Please take a moment to share the articles on social media, engage the authors with questions and comments below, and link to articles when appropriate if you have a blog or participate on forums of related topics. — SF

[mashshare]