Jeremy Frisch and Calin Butterfield are working together on concepts related to long-term development of ski and snowboard athletes.

Jeremy is the Owner and Director of Achieve Performance Training in Clinton, Massachusetts. Although he trains people of all ages and abilities, his main focus is on youth athletic development, physical education, and physical literacy. He is the former assistant strength and conditioning coach for the Holy Cross men’s basketball program. He also worked with at least eight other teams for the Crusaders. Prior to his time at Holy Cross, Frisch served as the sports performance director at Teamworks Sports Center in Acton (MA) and speed and strength coach for Athletes Edge Sports Training, and he did a strength and conditioning internship at Stanford University. Frisch is a 2007 graduate of Worcester State College, with a bachelor’s degree in health sciences and physical education. He is certified USA Weightlifting, USA Track and Field, and SFG 1. He was a member of the football and track teams during his days at Worcester State and Assumption College.

Calin Butterfield is the High-Performance Manager at U.S. Ski & Snowboard. Calin has been with U.S. Ski & Snowboard for four years, where he works closely with the sports medicine team as an “athletic development” coach on long-term rehabs and return to performance cases. In his role he also leads the integration with U.S. Ski and Snowboard clubs/academies to support talent and athlete development pathways and leads business development and education with medical partners. He previously worked for EXOS for nearly eight years as a coach across all different locations, including Phoenix, Dallas, and San Francisco. Calin earned a B.S. in Exercise and Sports Science from Oregon State University. He is a Certified Strength and Conditioning Specialist (NSCA), Level 1 FMC, and a Level 2 Certified Coach with USAW.

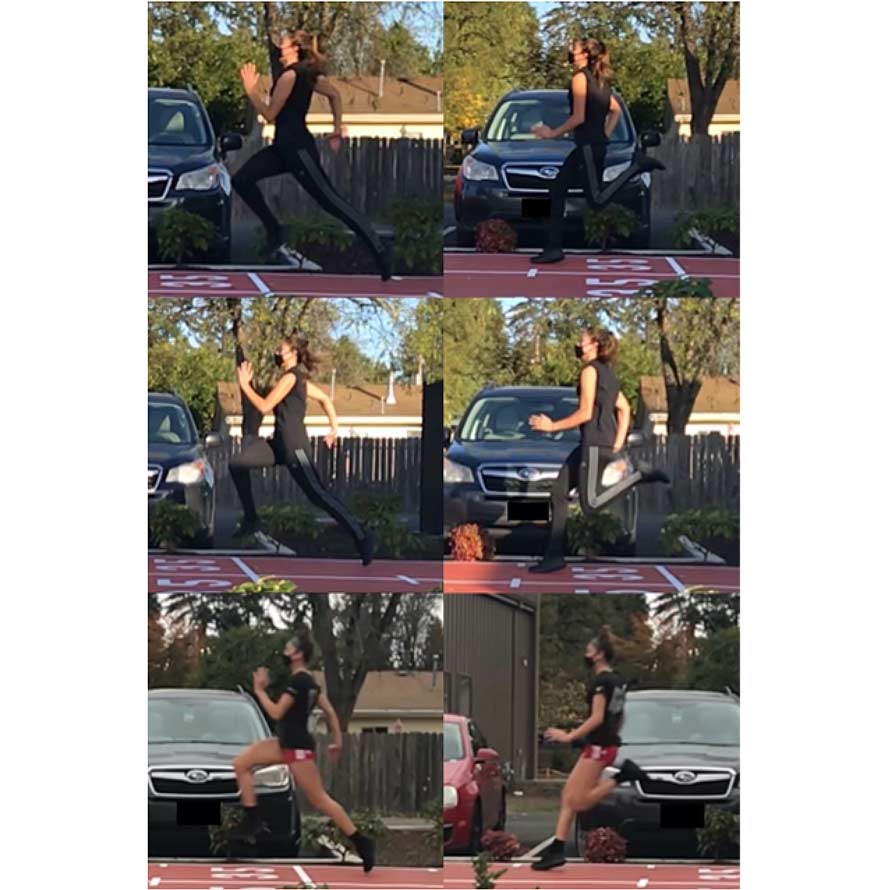

Jeremy and Calin talk about their collaboration on skiing, the use and progression of games with young athletes up to college level, plyometric progressions and advancing complexity, and how the natural warm-up process in ski and snowboard (terrain park) can give us ideas that we can port over into the way we prepare athletes for sport. They dive into the study of athletes in sports that demand fast reactions, impactful landings, high risk, and how rewards for creativity have a lot to offer when it comes to looking at our own training designs for the athletes we serve.

In this episode, Coach Jeremy Frisch, Calin Butterfield, and Joel Smith discuss:

- How gameplay fits into a sport like skiing.

- When people tend to peak in skiing and snowboarding, and how this fits into the proportion of game play at different ages.

- The power in connecting to the outcome and having multiple avenues to get to that outcome.

- The relationship between landing variability and chronic sport landing overload.

- Long-term development in skiing and supplementing with traditional land-based training.

What it looks like to build up an athlete in high-adrenaline sport training.