Throughout my career, I’ve received numerous phone calls and had many discussions with strength and conditioning professionals and sport coaches who have inquired how to initiate training their post-rehabilitated shoulder athlete and the exercise modifications, if any, that are necessary to incorporate into the weight room program design. I have worked diligently over the past two decades to address this concern. These inquiries and discussions have led to this article, which provides some of the weight room strategies that have been successfully utilized over the years to assist in the post-rehabilitation athlete’s training to return to optimal athletic performance.

Participation in athletics requires a proficiency in both the physical qualities and sport skills for the achievement of the desired success. Unfortunately, participating in athletics also presents the risk of physical injury due to the requirements of repetitive high-velocity movement, physical contact, and other unexpected circumstances that may arise during the athlete’s training, sport practice sessions, and game day competition. No anatomical structure is immune from this threat of injury, as the consequences of athletic participation encompass the entire body from head (concussions, facial lacerations, etc.) to toe (sprained ankles, jones fractures, etc.).

Numerous athletic injuries may also include concomitant anatomical structures such as an anterior cruciate ligament (ACL) tear with a corresponding meniscal tear of the knee or a rotator cuff tear with an associated labral tear of the shoulder. Many of these injuries will require surgical intervention, and many will not. However, in each of these scenarios, the healing continuum of the body will lead to the formation of collagen fibers to produce strong scar tissue, which may subsequently lead to a reduction in joint range of motion (ROM). With specific regard to the shoulder, the joint topic of this discussion, some surgeons may elect to create a “tighter” shoulder at the time of surgery to reestablish strong joint integrity as well as an intentional loss of some end range of shoulder motion. This loss of shoulder ROM is executed to avoid the vulnerable extreme ROM positions of possible injury.

At the time of the athlete’s shoulder injury and possible corrective surgery, it is likely that they will participate in a sports rehabilitation program. At the conclusion of their rehabilitation, they will likely return to their performance enhancement training to prepare for their next competitive sport season. Many of these post-rehabilitated shoulder conditions will initially (and possibly permanently) have weight room contraindications or postoperative restrictions in their ROM requiring exercise modifications during the athlete’s training. These shoulder exercise modifications are implemented to protect the shoulder surgery, avoid an exacerbation of the athlete’s shoulder condition, and ensure optimal weight room outcomes.

This article will present some weight room modifications for the S&C professional and sport coach to consider when establishing the post-rehabilitation shoulder athlete’s training program design.

Prerequisites for the Athlete’s Weight Room Participation

Significant requirements for the post-rehab shoulder athlete are shoulder range of motion, scapulohumeral rhythm, the deltoid-rotator cuff force couple, and work capacity. Share on XThere are various physical prerequisites that athletes must achieve and demonstrate during their shoulder rehabilitation prior to their approved participation in a formal weight room training environment. For the purpose of this discussion, four of these significant requirements are:

- Shoulder Range of Motion – Full shoulder ROM in all planes of motion, including rotations, should be achieved unless shoulder ROM was purposely restricted during surgery. Attention is made to attain the required shoulder ROM that correlates specifically to the sport of participation. As an example, the throwing athlete does not have to demonstrate symmetrical internal and external ROM but is required to display a symmetrical total rotational arc of motion1.

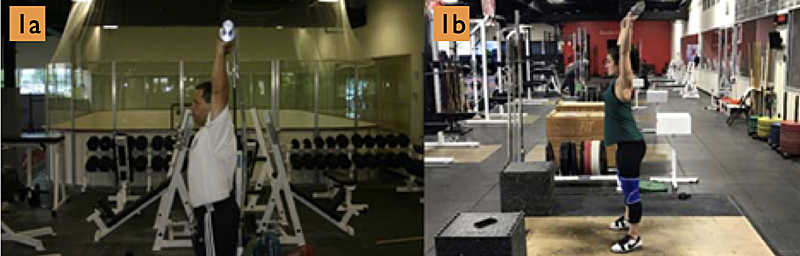

- The post-rehabilitated shoulder athlete will be expected to perform overhead resistance and conditioning exercises such as the bench press, overhead press, push press, jerks, med ball tempo, etc. during their training. Therefore, athletes without surgical ROM restrictions must achieve both passive and active full overhead arm elevation (figures 1a and 1b), which is confirmed by the olecranon of the elbow aligning with the ear. A lack of overhead shoulder ROM will result in increased stress to the shoulder and spinal compensatory extension during overhead exercise execution2, while comparative upper extremity elevated (shoulder flexion) deficits of as little as 5 degrees will increase the risk of elbow injury in throwers by almost threefold3.

- Scapulohumeral Rhythm – The scapulohumeral rhythm of the shoulder is the ratio of glenohumeral to scapulothoracic motion that transpires during arm elevation. This ratio is determined by dividing the total amount of shoulder elevation (glenohumeral) by the scapular upward rotation (scapulothoracic). This ratio is 2:1 in unloaded shoulder elevation but adjusts to approximately 4.5:1 when lifting heavy loads overhead4. An athlete must display a reestablished unloaded scapulohumeral rhythm of 2:1 prior to attempting to lift weights overhead.

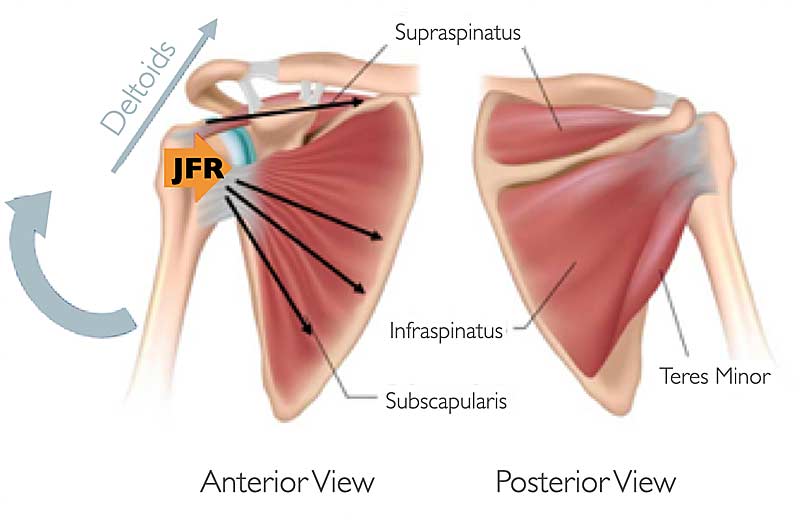

- The Deltoid-Rotator Cuff Force Couple – A joint force couple transpires when two equal but opposite directed forces act simultaneously on opposite sides of an axis to produce a rotation. During arm elevation, a glenohumeral force couple arises when the deltoid muscle group produces a superiorly directed force as the rotator cuff musculature produces both compressive (joint reaction force) and inferiorly directed forces (figure 2). The recommended rotator cuff strength would require the external rotators to be approximately 66% to 75% of the strength of the internal rotators to help ensure a suitable force couple.

- Work Capacity – An appropriate work capacity ensures that strength, as well as the additional physical qualities established during the rehabilitation/training process, is produced repetitively over time, avoiding the onset of excessive shoulder complex and total body fatigue. With specific regard to the shoulder complex, a fatigued rotator cuff will be unable to offset the force produced by the deltoid muscle group, thereby disrupting the deltoid-rotator cuff force couple. This altered force couple results in a consequential superior and inferior migration of the humeral head in the glenoid fossa during arm elevation and with the arm resting at the side, respectively.

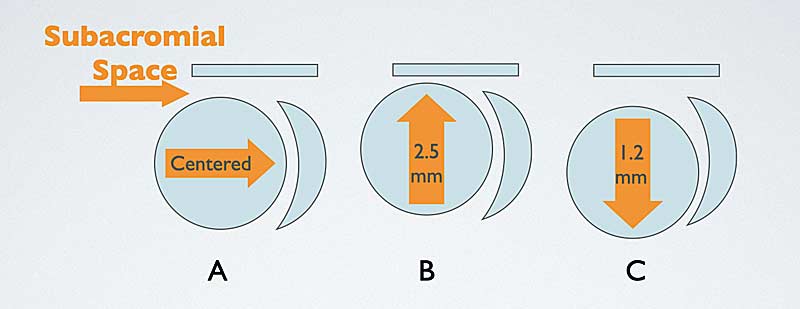

It is recognized that an attempted arm elevation with a fatigued rotator cuff mimics the same superior migration of the humeral head in the glenoid fossa that transpires during an attempted arm elevation with a torn rotator cuff. Shen-Kai5 has reported that induced fatigue in the rotator cuff musculature results in average increases in superior humeral head migration of 2.5 millimeters during arm elevation and average increases in inferior humeral head migration of 1.2 mm with the arm resting at the side (figure 3). It is also reported that at 0 degrees of shoulder abduction (arm at the side), the available subacromial space for rotator cuff “clearance” is approximately 11 mm, 5.7 mm at 90 degrees of abduction, and 4.8 mm at 120 degrees of abduction6. The fatigue factor of a 2.5 mm increase in superior humeral head migration potentially decreases the subacromial space by up to 52% at 120 degrees of arm elevation or higher.

(A) normal humeral head centered alignment, (B) superior humeral head migration, and (C) inferior humeral head migration.

The scapula musculature also presents with concerns as a result of the shoulder complex muscle fatigue. During arm elevation with fatigued scapula musculature, the scapula will have a decreased poster tilt (or increased anterior tilt), increased protraction, and increased upward rotation with corresponding decreased lower trapezius muscle activity. This altered repositioning of the scapula also decreases the subacromial space. The altered combination of humeral head migration and scapula repositioning reduces the subacromial space of the shoulder, setting the stage for possible impingement pathology during repetitive overhead exercise performance. The consequential effect of fatigue on joint kinematics reinforces the significance of an appropriate training program design for the prevention of excessive muscle fatigue to ensure optimal training performance and provide ideal athlete recovery prior to their next training session.

The foundation for our modification of upper extremity weight room exercises was published in an article more than two decades ago by my good friends Tony Decker and Marty Fees7. These exercise modifications are still relevant to this day, as we have continued to advance and adapt them over the years in both the clinical and weight room settings. I present some of these exercise modifications and their justification below.

Bench Press Modifications for the Rotator Cuff and Impingement

A common question asked by the athlete during their shoulder rehabilitation is “When can I start bench pressing?” It is also common to hear many high school athletes ask, “How much can you bench?” when comparing their strength levels to their peers. The bench press is a very popularly employed upper extremity strength exercise in the athlete’s training program design.

The traditional flat bench press involves a combination of motions in the sagittal (flexion/extension), coronal (abduction/adduction), and transverse (horizontal adduction/abduction) planes of the body. The bench press exercise places high levels of repetitive stress on the rotator cuff and the long head of the biceps, as well as compressive forces at the distal clavicle that can lead to the condition of osteolysis of the shoulder.

Post-rehabilitated shoulder athletes treated for rotator cuff and impingement pathology should limit their barbell hand spacing to no wider than 1.5x their bi-acromial width. Share on XPost-rehabilitated shoulder athletes treated for rotator cuff and impingement pathology are prescribed specific barbell hand spacing and, if necessary, grip modifications for bench pressing. For these shoulder conditions, the athlete should limit their hand spacing to no wider than 1.5 times their bi-acromial width (figures 4a and 4b).

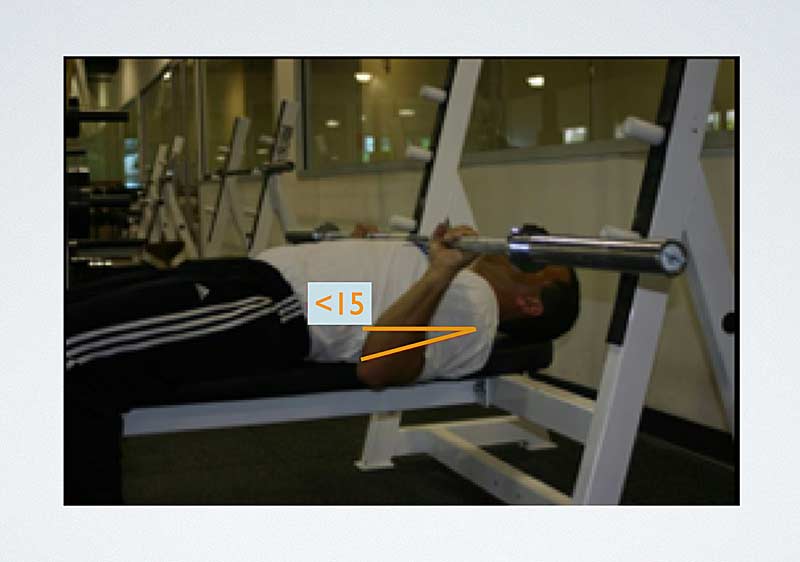

This narrow barbell hand spacing reduces rotator cuff and biceps tendon complex requirements for humeral head stabilization. This hand spacing also maintains shoulder abduction and extension at less than 45 degrees and 15 degrees, respectively, (figure 5) while aligning the clavicular border of the pectoralis major and the biceps muscles to a mechanically advantageous position to assist in shoulder flexion, decrease stress upon the long head of the biceps, and reduce compressive forces at the distal clavicle. This hand spacing also allows for a more superior barbell touch point to the xiphoid process, thus decreasing the net torque placed upon the shoulder.

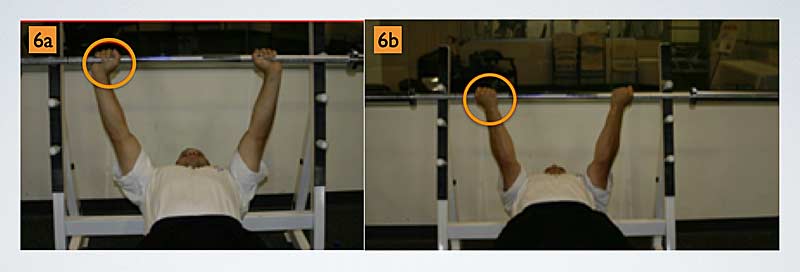

The barbell grip selection also influences the stresses placed upon the shoulder. The overhand grip of full pronation (figure 6a) and underhand grip of full supination (figure 6b) affect the biceps and supraspinatus musculotendon portion of the rotator cuff, respectively.

The overhand grip moves the biceps tendon from under the acromion via the internal rotation of the shoulder. However, this full pronation grip positions the supraspinatus muscle of the rotator cuff beneath the acromion. The underhand grip rotates the supraspinatus posteriorly away from the undersurface of the acromion, while the long head of the biceps is now positioned beneath the acromion.

For those athletes who present with supraspinatus pathology, initial flat bench press training with a supinated grip is a recommended consideration. As the athlete is monitored over time without reported exacerbation of their shoulder condition, you may then employ the traditional overhand grip during training.

Bench Press Modifications for Anterior Shoulder Instability and SLAP Lesions

When executing the flat bench press exercise, a mandatory training partner-assisted “liftoff” of the barbell from the supporting barbell stanchions should occur at all times. This will avoid the overhead shoulder flexion, abduction, and external rotation or “high five” shoulder and arm position that is very vulnerable to injury. The previously described 1.5 times or less bi-acromial barbell hand spacing maintains a shoulder position below 90 degrees of shoulder flexion and 45 degrees of shoulder abduction.

The athlete should avoid incline bench pressing for these shoulder conditions, as this exercise mimics the overhead “high five” vulnerable shoulder position. This is especially true for athletes who present with anterior and/or anteroinferior shoulder instability, as well as those who are post anterior-stabilization surgery. If you desire an alternative bench press exercise for a training variation, you can incorporate the decline bench press into this shoulder pathology classification program design.

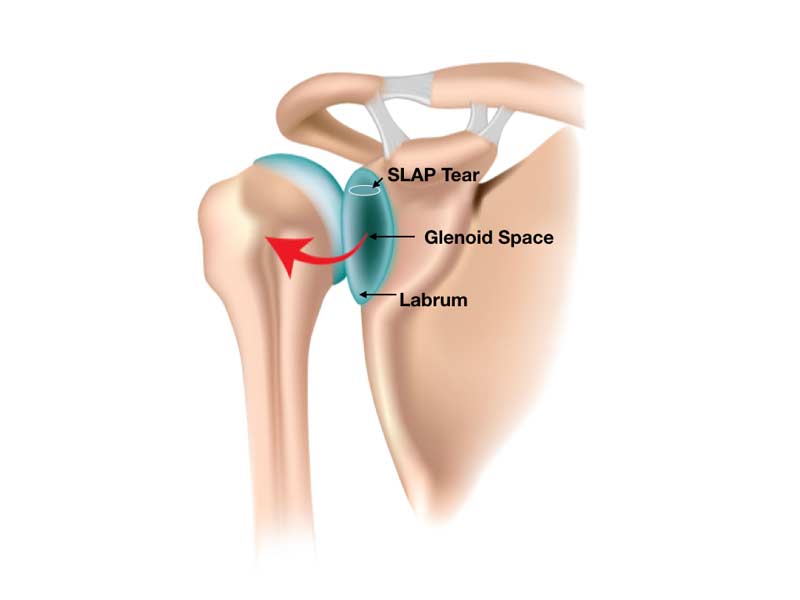

SLAP is an acronym for superior labrum anterior posterior, as these lesions occur at the glenoid labrum of the shoulder. The long head of the biceps attaches to the glenoid labrum at the 12 o’clock position (figure 7). SLAP lesion classifications include various levels of involvement of the long head of the biceps tendon, from fraying to various labral disorders with or without biceps anchor detachment.

It is recommended that athletes alternate the overhand and underhand grip variations on bench press training days to limit the accumulative microtrauma stress placed upon the long head of the biceps. I should note that a paradox exists with the use of these two barbell grips with regard to SLAP tears. The overhand grip removes the biceps from under the acromion; however, due to the grip’s full forearm pronation, the exercise performance stresses the attachment of the long head of the biceps. The underhand grip of full supination positions the long head of the biceps tendon under the acromion but decreases the stress on the biceps tendon during exercise performance.

You may use the overhand and underhand barbell grip variations, along with the varying of programmed weight intensity (periodization), for training variety on alternate bench press training days. Utilizing both barbell grip variations in the same training session is not recommended.

Bench Press Modifications for Posterior Shoulder Instability

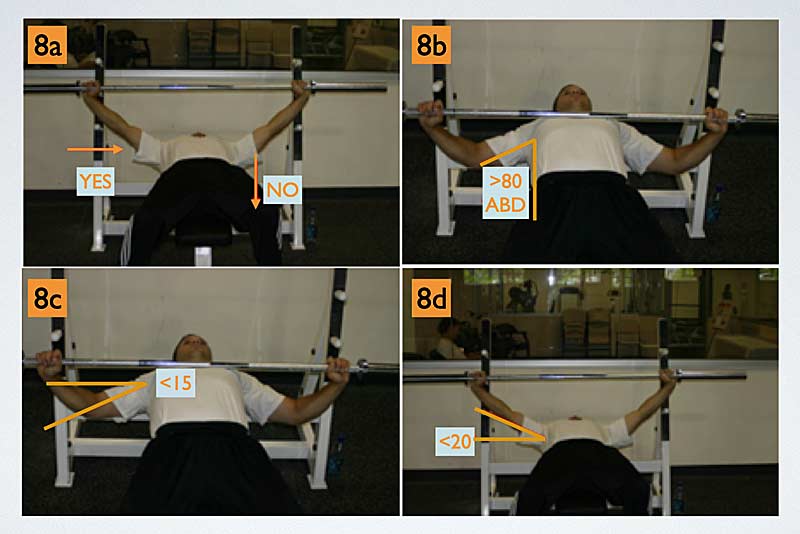

Posterior shoulder instability usually presents in athletes such as football offensive linemen. During the skill of pass blocking, high-velocity impact stresses are received by narrowly spaced and extended arms that transfer these forces to the posterior aspect of the shoulder. The previously described 1.5x bi-acromial (or less) barbell hand spacing is now contraindicated, as this hand spacing will increase the stress directly applied to the posterior aspect of the shoulder with the arms fully extended. Athletes presenting with or who have a history of posterior shoulder instability require a barbell hand spacing of greater than two times their bi-acromial width.

This wider hand spacing increases shoulder torque by 1.5 times compared to the narrower hand spacing; however, this wider hand spacing allows for a better structural approximation of the humeral head toward the center of the glenoid fossa. This improved shoulder joint structural approximation results in decreased strain upon the soft tissue structures at the posterior aspect of the shoulder (figure 8a). This increased barbell hand width position results in shoulder abduction at greater than 80 degrees (figure 8b), and horizontal abduction is greater than 15 degrees (figure 8c) at the initiation of the concentric phase of the lift. Shoulder horizontal adduction is less than 20 degrees (figure 8d) at the conclusion of the concentric phase of the exercise performance.

Bench Press Modifications for Pectoralis Muscle Tears

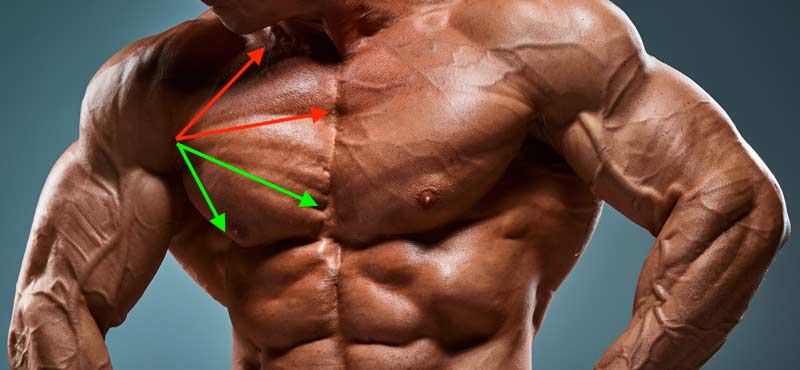

Pectoralis muscle tears occur in the weight room, during athletic competition, and during daily activity, with more than 200 reported cases in the literature. The pectoralis muscle consists of two heads, the clavicular and the sternocostal. Some authors continue to separate the sternocostal portion of the pectoralis muscle into a superior segment and an inferior segment (figure 9).

During the descent (eccentric contraction) of a heavy loaded barbell, the touch point position of shoulder extension, abduction, and external rotation can become the mechanism of pectoralis muscle injury. The clavicular and superior sternocostal segments of the pectorals are unipennate parallel muscle fibers, while the muscle fibers of the inferior sternocostal segment are multipennate. These multipennate fibers twist 180 degrees at their insertion on the humerus, placing this pectoral segment at a distinct mechanical disadvantage. This disadvantage results in a disproportionate lengthening of the inferior sternocostal muscle fibers at 30 degrees of shoulder extension, the final portion of the eccentric phase at the barbell touch point. The heavy loaded eccentric phase at touch point maximally stretches these muscle fibers, subjecting them to the “plastic range” on the stress-strain curve of musculotendinous soft tissue and exposing them to possible rupture/injury.

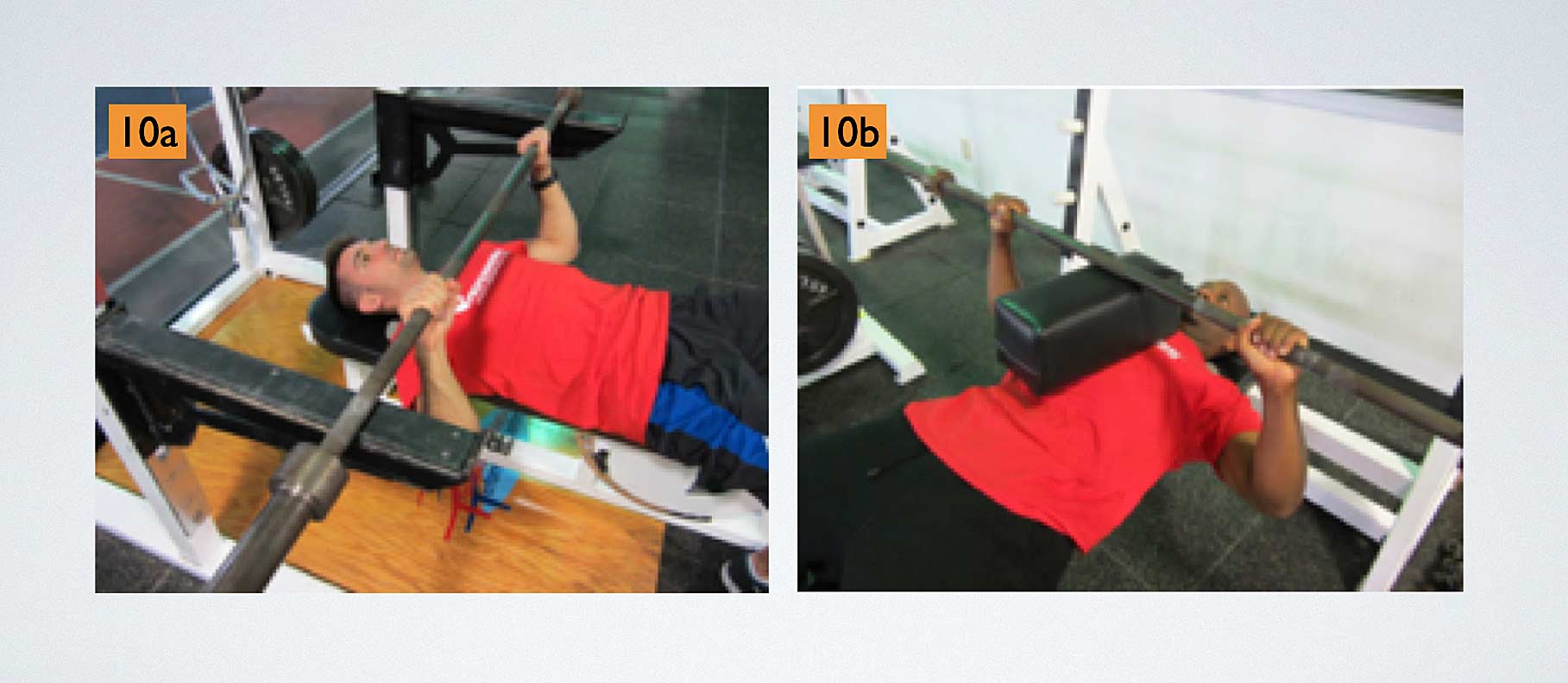

At the time of the post-rehabilitated pectoralis tear/surgical repair and the athlete’s reintroduction to the bench press exercise, a narrow barbell hand spacing of a bi-acromial width of 1.5x or less is recommended. You should incorporate rack starts (figure 10a), board presses (figure 10b), and floor presses to limit the athlete’s shoulder extension to 0 degrees (neutral) at the barbell touch point upon the chest. By limiting shoulder extension to 0 degrees, the sternocostal musculotendinous soft tissue avoids the plastic range on the stress-strain curve. When prescribing the board press modification, we prefer the use of a foam cushion (figure 10b) versus wooden boards to prohibit the athlete from relaxing and thus maintaining muscle “tension” during the barbell transition from the eccentric descent to touch point to concentric ascent.

A rack start is a bench press exercise modification where the barbell is placed on squat rack stanchions or power rack steel pins at or as close as possible to a pain-free and comfortable chest touch point position (figure 10a). The advantage of a rack start is the bench press exercise starts from or close to the barbell touch point, the most vulnerable position for pectoral injury. If the athlete feels pain or discomfort when initially attempting to raise the barbell from the rack position, the exercise immediately stops, as the barbell is safely supported.

During the traditional flat bench press exercise performance, once a successful barbell liftoff transpires, the athlete now “owns” the weight. If there is pain or discomfort during the eccentric descent or at the barbell touch point, it places the athlete in a very precarious position for injury, as they are now likely unable to return the barbell to the starting extended arm position.

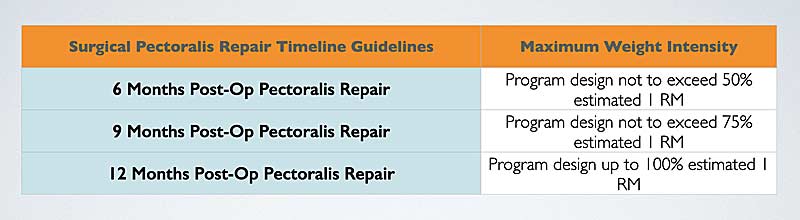

The post-rehabilitation athlete who has had their pectoralis tear surgically repaired has likely not bench pressed in quite some time. Therefore, their previous personal best bench press performance and workout program weights should not be the standard for their returning program design. The athlete should not attempt to bench press prior to their six-month post-surgery date and without their surgeon and rehabilitation professional’s approval. When the athlete returns to their weight room training, the S&C professional will likely have to make a “guesstimate” of the athlete’s bench press abilities. Figure 11 presents postsurgical pectoralis repair bench press guidelines.

Unloading the Barbell Intensity at the Bench Press Touch Point

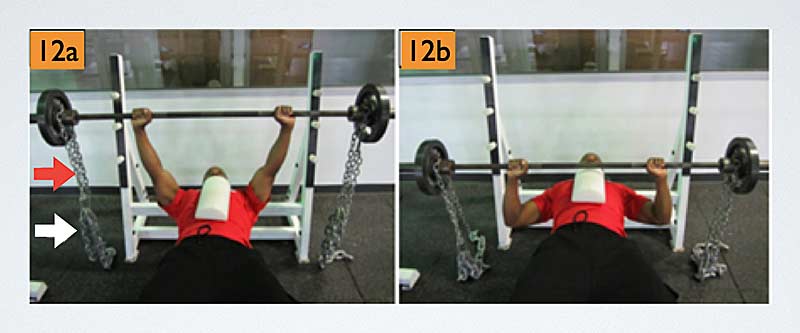

Regardless of the athlete’s present or past condition or surgery, a very high level of stress is applied to the shoulder at the bench press barbell touch point. Therefore, it is certainly feasible to unload this barbell position at the time the athlete returns to training. Our preference for this unloading process is the application of chains versus rubber bands to the barbell.

It is certainly feasible to unload the bench press barbell position when the athlete returns to training. For this unloading process, we prefer applying chains versus rubber bands to the barbell. Share on XThe rubber bands apply resistance via their attachment to either the bench or the floor, possibly affecting the barbell pathway during the bench press performance. Since chains are only attached to the barbell, the barbell pathway is determined by the exercising athlete. As the attached chain makes contact with the ground surface, the barbell weight intensity is progressively reduced until the time of the barbell touch point. During the barbell ascent, the chains “reload” the barbell, resulting in a gradual increase in the exercise weight intensity until the arms are fully extended. Our preferred method to apply chain resistance to the bench press exercise is with the use of leader chains.

Leader chains (figure 12a) allow for accuracy in determining specific loads at the initiation and touch point portions of the bench press exercise. The weight of the leader chains and the weight of the chains they support are added to the weight of the loaded barbell, providing the total weight of the exercise performance at barbell liftoff. During the barbell descent, the weight intensity progressively decreases until reaching the touch point on the athlete’s chest.

At this vulnerable barbell position for both the shoulder and pectorals, an accurate weight intensity is accounted for, since the previously measured barbell and leader chain weights apply resistance as the additional weighted chains have been unloaded and rest on the floor (figure 12b). This loading process is quite different when compared to the technique of simply hanging chains in the absence of leader chains, where the accurate weight of the barbell when achieving the touch point position is relatively unknown.

The initial program design for the post-rehabilitation shoulder and pectoral athlete should be conservative in nature. An athlete, S&C professional, or sport coach who is too aggressive in their program design will increase the risk of rotator cuff, biceps, and pectoralis tendinitis and possible reinjury. The onset of a tendinitis will not only regress the athlete’s training, but it is a condition that may require an extended period of time to resolve.

The Shoulder Press

When appropriate, I am an advocate of the shoulder press exercise, and I previously wrote an article supporting overhead exercise performance on SimpliFaster. This article emphasized the overhead exercise performance with the barbell positioned in front of the neck with an exercise pathway in the plane of the scapula. The front-of-the-neck barbell position is the preferred overhead exercise if the post-rehabilitated athlete has met all of the physical prerequisites prior to attempting this exercise. This is especially true of the post-rehabilitated pectoral tear athlete, as it is highly unlikely that a subsequent injury or rupture of a pectoral muscle will transpire when lifting weights overhead.

An alternative overhead shoulder exercise is the behind-the-neck press. When prescribing exercises for athletes with present or past shoulder pathology, exercise caution with this barbell position. The behind-the-neck press involves motion in both the sagittal and coronal planes of the body. The starting exercise position places the barbell on the upper trapezius muscles at the level of the first thoracic vertebrae. This starting barbell position places the arms in abduction, and very often an external rotation of greater than 90 degrees (figure 13), as the scapula position also adjusts via retraction from the plane of the scapula to the coronal plane.

This repositioning of the scapula also adjusts the length-tension of the rotator cuff, resulting in a less-than-optimal force production from these muscles during exercise execution. The behind-the-neck shoulder dynamic external rotation range of motion has often been reported as greater than passive measurements2, thus increasing the risk of possible shoulder injury. Passive shoulder external rotation should match or exceed the dynamic external rotation exercise requirements prior to performing the behind-the-neck press barbell exercise.

Behind-the-neck exercise performance is required for athletes participating in Olympic weightlifting or who utilize the Olympic lifts or accessory exercises of the Olympic lifts during their performance enhancement training. Loaded shoulder abduction, external rotation, and high-five positions place stress upon the rotator cuff, inferior glenohumeral ligaments, anterior soft tissue and labral structures, SLAP lesions, and those athletes who present with shoulder impingement and anterior glenohumeral instability. When appropriately prescribed, it is recommended to initiate behind-the-neck exercises from a higher barbell position at the base of the skull at ear level. This higher barbell position will reduce the exercise range of motion and stress to the anterior and anteroinferior soft tissues structures of the shoulder.

The Clean and Power Clean

The clean and the power clean are commonly programmed exercises for the enhancement of the athlete’s power, rate of force production, and applied impulse. Both the clean and the power clean are total body exercises that require motions in both the sagittal and coronal planes of the body. The post-rehabilitation concerns that arise with these exercises, especially the clean, are with regard to anterior/anteroinferior soft tissue structures, and more specifically the biceps-labral complex, and SLAP lesions.

Large shoulder distraction forces are placed upon the biceps-labral complex, especially during the first pull, and then followed by the acceleration phase of these exercises. Therefore, the clean exercise is not recommended in the initial programming for the post-rehabilitated SLAP shoulder athlete due to the prolonged distraction forces that occur via the initiation of the exercise from the floor. For this reason, the power clean exercise performed from blocks is the preferred choice in this post-rehabilitation athletic population.

Additionally, the catching of the barbell requires both shoulder and elbow flexion, which applies stress to the biceps tendon. If the athlete reports discomfort with the catching of the barbell, the catch should be avoided and revisited after a period of training. Although various exercise adjustments may be necessary, along with the monitoring of an athlete’s tolerance to exercise performance, some specific modification guidelines are recommended for the post-rehabilitated SLAP athlete. These guidelines include the following:

- Initiate the power clean execution from blocks, thus eliminating the support of the weight of the barbell (distraction forces at the shoulder) with the arms extended.

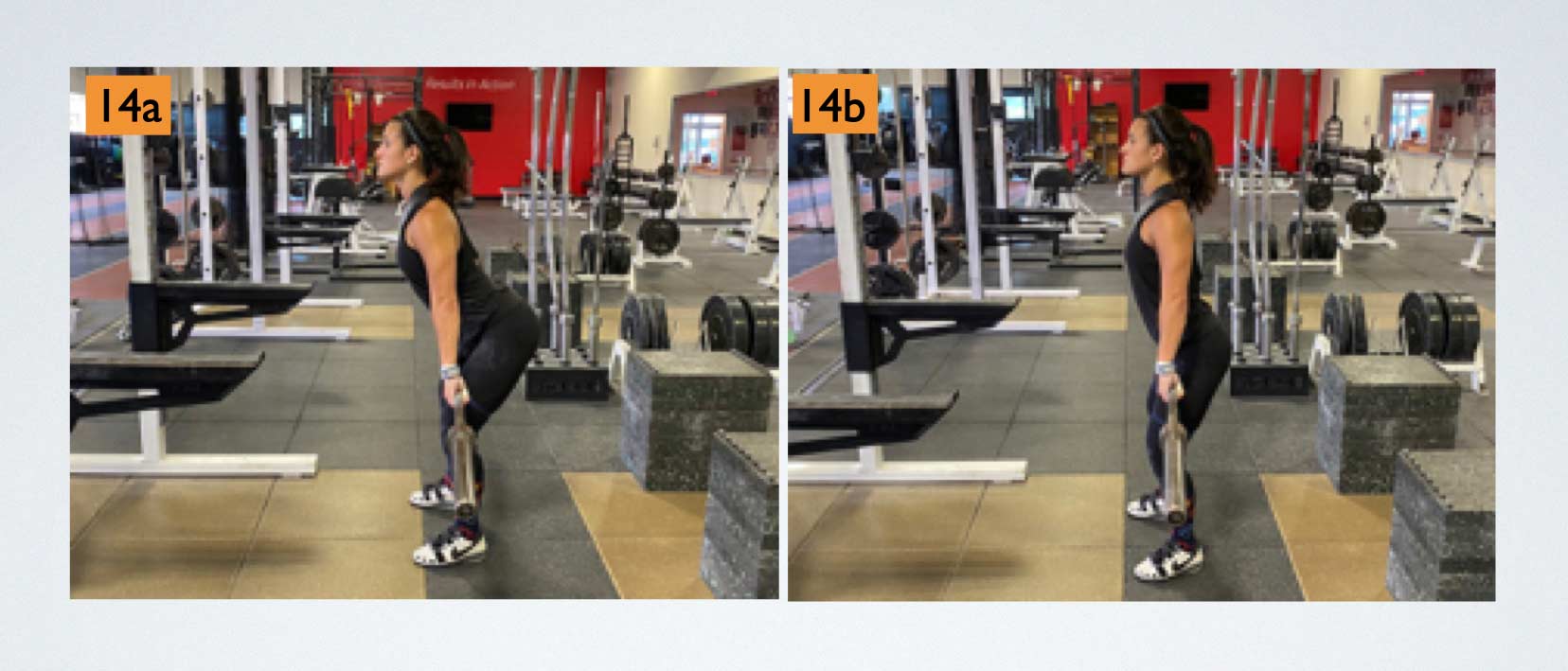

- Prescribe initial exercise execution with the barbell positioned at approximately above the knee to mid-thigh (figure 14a). The exercise may be appropriately advanced to an elevated barbell position at approximately the mid-thigh to the hips (figure 14b).

- If the athlete reports shoulder discomfort during the catching of the barbell, clean pulls should replace the power clean in the athlete’s program design.

- Utilize bumper weight plates, if available, during the exercise performance. This will allow the athlete to freely return (drop) the barbell to the blocks upon completion of each exercise repetition to avoid high distraction forces at the shoulder.

- Initial exercise programming should include a velocity-based training philosophy utilizing lighter weight intensities executed at higher barbell velocities.

The Squat

The squat exercise is a total body strength exercise incorporating both the lower and upper extremities. Athletes traditionally perform the exercise with the barbell across the back, so it is therefore known as the back squat. During the execution of the back squat, the upper extremities are involved in a combination of motions in the transverse (external rotation) and coronal (abduction) planes of the body. The concerns for loading an abducted and externally rotated shoulder have been previously described in the behind-the-neck press exercise section of this discussion. These same shoulder position concerns advocate for squat exercise modifications for the post-rehabilitated shoulder athlete’s program design.

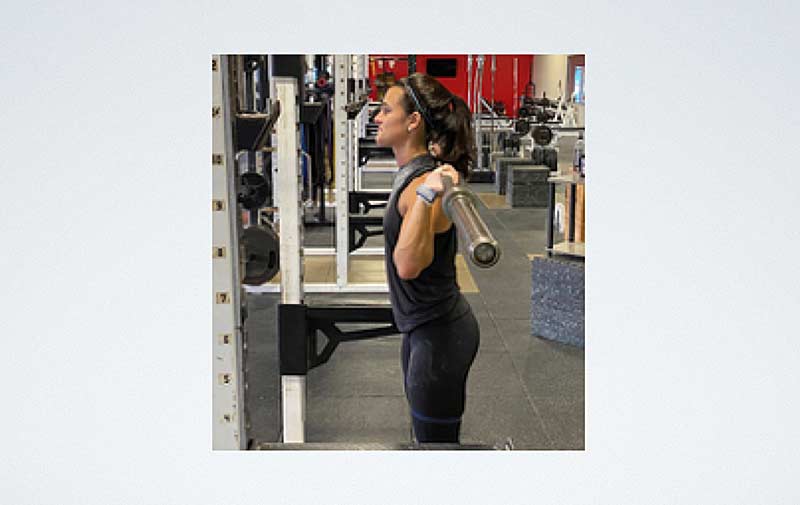

The first exercise modification includes the use of a safety squat bar during the athlete’s exercise performance. The safety squat bar places the shoulder in a less stressful position of shoulder flexion, adduction (adduction neutral), and internal rotation. When utilizing the safety squat bar, the athlete has the option to hold onto the bar or to incorporate a bilateral hand support technique with the squat rack.

When opting for a bilateral hand support exercise technique, a “holding surface” on the squat rack at an initial height level equaling 60 degrees to 80 degrees of shoulder flexion is advised. Too low a holding height level may promote an increase in spinal flexion at the initiation and perhaps throughout the athlete’s squat exercise performance. At the conclusion of the squat descent, shoulder elevation should not exceed approximately 95 degrees to 100 degrees, the same shoulder ROM that occurs at the extended arm position during the bench press exercise. While the arms increase in elevation during the squat descent, the athlete should remain erect throughout the exercise performance.

When using this technique, the hand placement occurs with the palms open to maintain balance yet prohibit pulling on the holding surface. The inability to pull on the holding surface will omit shoulder distraction forces that may transpire during the exercise execution with a closed hand grip. If at any time the athlete struggles during this open-handed bilateral support technique, they can quickly grasp the holding surface, as hand contact is always maintained to ensure a safe exercise performance. Lighter weight intensities are recommended until the time the athlete comfortably adapts to this exercise technique.

Another option for the back squat is the utilization of the buffalo barbell (figure 15). The curved nature of the buffalo barbell allows for a wider hand placement at the lower curved barbell ends, which decreases the amount of required shoulder abduction and external rotation during the squat exercise performance.

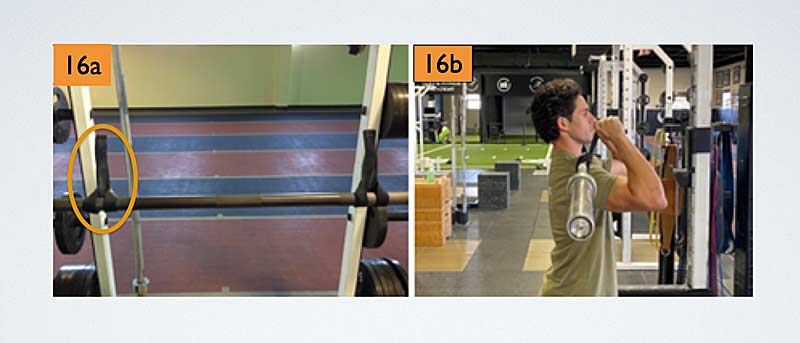

If a safety squat bar and buffalo barbell are not available for the athlete’s training, a third modification/option is the front squat. The execution of the front squat exercise still stresses the lower extremity and hip muscles, as the barbell is now supported mainly by the anterior deltoids and balanced with the hands. The front squat positions the shoulder at 80 degrees to 90 degrees of flexion, less than 15 degrees of external rotation, and neutral abduction, a position preferred for the shoulder athlete’s squat exercise performance. If the athlete lacks the wrist, hand, and elbow flexibility to maintain the barbell during the front squat exercise, straps may be inverted and attached to the barbell (figure 16a) to assist in the front squat exercise execution (figure 16b).

Initial programming of the front squat exercise intensity should be at levels of 50% to 60% of the athlete’s back squat capabilities. The S&C professional may increase the exercise intensity over time (up to approximately 80% of back squat capabilities) while they monitor and receive feedback from the athlete. The modified back squat and front squat may be alternated during the athlete’s training days. Additional lower extremity strength training options include the use of belt squats and the kBox flywheel with a harness. The belt squat and kBox flywheel allow for lower extremity strength enhancement with the exclusion of the upper extremities during the exercise performance.

Summary

The shoulder is the most mobile joint of the body when compared to the osseous stability and protection provided at the hip joint, the other ball and socket joint of the body. This mobility contributes to the shoulder’s vulnerability to injury. The athlete who presents with a shoulder injury may or may not require surgery; however, after injury/surgery rehabilitation followed by post-rehabilitation, performance enhancement training will likely occur.

The shoulder is the most mobile joint of the body… This mobility contributes to the shoulder’s vulnerability to injury. Share on XThis article has provided the S&C professional, as well as the sport coach, with a few exercise modifications for consideration in the weight room training of the post-rehabilitated shoulder athlete. These exercise modifications may be utilized during the athlete’s initial training and eventually discontinued as the athlete physically adapts over the course of their training. These exercise modifications may also play a permanent role in the athlete’s training due to prescribed shoulder exercise contraindications as well as intended postoperative ROM restrictions. The S&C professional should also maintain communication with their rehabilitation professionals, team physicians, and surgeons to determine the best post-shoulder rehabilitation training program design and program design progressions for their athlete.

Since you’re here…

…we have a small favor to ask. More people are reading SimpliFaster than ever, and each week we bring you compelling content from coaches, sport scientists, and physiotherapists who are devoted to building better athletes. Please take a moment to share the articles on social media, engage the authors with questions and comments below, and link to articles when appropriate if you have a blog or participate on forums of related topics. — SF

References

1. Wilk KE, Macrina LC, Fleisig GS, et al. “Correlation of Glenohumeral Internal Rotation Deficit and Total Rotational Motion to shoulder Injuries in Professional Baseball Pitchers.” American Journal of Sports Medicine. 2011;39(2):329-335.

2. McKean MR and Burkett BJ. “Overhead shoulder press – In-front of the head or behind the head?” Journal of Sport and Health Science. 2015;4(3):250-257.

3. Wilk KE, Macrina LC, Fleisig GS, et al. “Deficits in glenohumeral passive range of motion increase risk of elbow injury in professional baseball pitchers: a prospective study.” American Journal of Sports Medicine. 2014;42(9):2075-2081.

4. McQuade KJ and Smidt GL. “Dynamic scapulohumeral rhythm: The effects of an external resistance during elevation of the arm in the scapula plane.” Journal of Orthopaedic & Sports Physical Therapy. 1998;27:125-133.

5. Shen-Kai C, Simonian PT, Wickiewicz TL, Otis JC, and Warren RF. “Radiographic evaluation of glenohumeral kinematics: A muscle fatigue model.” Journal of Shoulder and Elbow Surgery. 1999;8(1):49-52.

6. Soslowsky LJ, Flatow EL, Bigliani LU, and Mow VC. “Articular geometry of the glenohumeral joint.” Clinical Orthopaedics and Related Research. 1992;(285):181–190.

7. Fees M, Decker T, Snyder-Mackler L, and Axe MJ. “Upper Extremity Weight-Training Modifications for the Injured Athlete.” American Journal of Sports Medicine. 1998;26(5):732-742.

Jonas Tawiah-Dodoo is the head coach and founder of Speedworks. He was a part of the UK Athletics Apprentice Coach program in the four-year lead-up to the London 2012 Olympics, working with world-renowned coaches Dan Pfaff and Stuart McMillan. His experience in sport is not limited to athletics, as he has worked with rugby for several years.

Jonas Tawiah-Dodoo is the head coach and founder of Speedworks. He was a part of the UK Athletics Apprentice Coach program in the four-year lead-up to the London 2012 Olympics, working with world-renowned coaches Dan Pfaff and Stuart McMillan. His experience in sport is not limited to athletics, as he has worked with rugby for several years.