Out of all of the events in track and field, there is no doubt triple jump is my favorite to watch. The speed, strength, power, elasticity, and coordination required to be successful in the event is unmatched, in my opinion, yet it remains unnoticed by the general public. There are many reasons for this, starting with the way track and field is broadcast, but I hope this article will result in greater interest and appreciation of the event.

The speed, strength, power, elasticity, and coordination required to be successful in the triple jump event is unmatched, yet it remains unnoticed by the general public, says @HFJumps. Share on XWhile the target of this article will be track and field coaches, I truly believe there is something here for every coach and athlete whose sport requires the aforementioned characteristics necessary to be successful in the event. I know that if I still coached football, little would make me more excited than hearing a skill position player was being trained to be a triple jumper. The same goes for just about any basketball player. I think it is very reasonable to say that a professional triple jumper would have a pretty darn good Euro step, and there is no doubt that triple jump training would help basketball players develop theirs, amongst other skills.

If you still are not sold on triple jump being an incredible feat of athleticism, check out this video of the 2012 Olympics. I have spent hours watching this in its entirety, and besides being amazed, I also notice new nuances in the event. Analyzing the similarities and differences between the jumpers has been extremely important in my development as a coach within the event.

I also hope that watching the video causes you to have great appreciation for Christian Taylor, who is, in my opinion, the best athlete in the world that nobody knows about. In the video, Taylor’s sequence is left, left, right. What is more remarkable is that four years later in Rio, Taylor repeated his gold-medal performance, but with a right, right, left sequence! This is only rivaled by Rocky Balboa switching to boxing right-handed to defeat Apollo Creed in their rematch. The battles Taylor and Will Claye have had over the years have been epic, and I look forward to more of them heading into the 2021 games!

Posture

It is universally accepted that posture is a key component to quality sprinting. Quality posture can lead an athlete to apply a higher-quality force vector into the ground, which could result in a better performance while decreasing the chance of injury. Whenever an athlete leaves the ground in a jumping event, postural errors in sprinting are amplified in the air. In the case of the triple jump, this happens threefold. Because of this, the basis of a successful triple jump can be viewed as the athlete attaining quality posture during sprinting and preserving it throughout the jump. Limb range of motion and distance covered during each phase will be based on the power capabilities of the athlete, but regardless of whether an athlete is a novice or a seasoned veteran, posture is a commonality that we must always prioritize.

Regardless of whether an athlete is a novice or a seasoned veteran, posture is a commonality that we must always prioritize, says @HFJumps. Share on XOne of the biggest problems with triple jump is athletes being rushed into the event. I have been guilty of not identifying athletes who may be successful in the triple jump until the end of a season. Upon realizing an average performance would result in our team earning championship season points, we found athletes who were willing to give it a try. While they were able to complete successful attempts, being rushed into the event caused bad habits to be formed (and hard to break) in future years.

What I have realized as I have aged is that it is not worth sacrificing athlete development for a few points at a conference meet. I now treat training triple jump like cooking a brisket—low and slow. When watching elite athletes triple jumping, it is immediately apparent that it is an event made for grown people. I often train all of our jumpers as if they will become a triple jumper one day; however, only a handful actually end up competing in the event.

A standard progression for an athlete who has no experience jumping in our program would be to try high and/or long jump their freshman year, while completing various drills and activities that would allow them to try triple jump their sophomore year if they are ready. Some may not be ready until they are juniors or seniors, and that is okay. Moving along patiently allows athletes to develop quality motor patterns, so by the time they need to produce the significant power the event requires, they are able to do so without issue.

Prominent Technical Flaws

Besides being on a never-ending quest to enhance sprinting form, there are three technical components I have found to have the biggest bang for the buck when it comes to addressing triple jump performance. Utilizing Gary Winkler’s analogy of always looking upstream, these items occur in the beginning, middle, and end of the first phase.

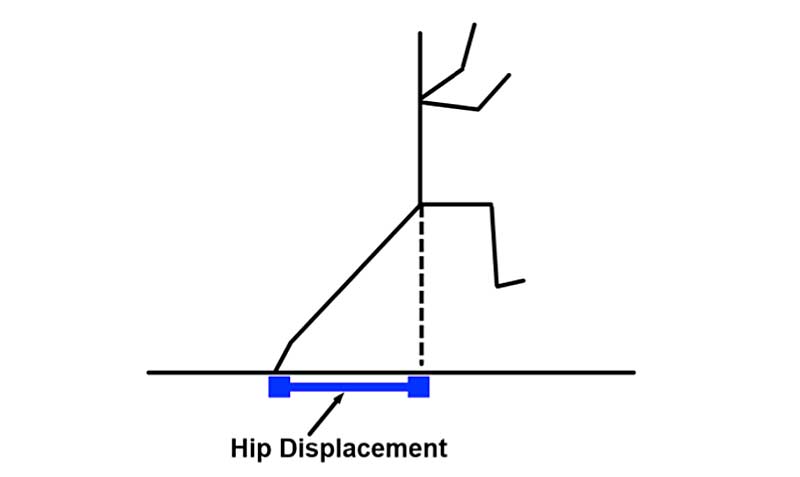

First is achieving quality hip displacement at the board. Hip displacement is the distance the hips are in front of the stance leg just before it leaves the ground. There are a number of reasons this is important. For one, having a high degree of displacement tends to allow the athlete to travel in a lower trajectory.

If you attend a high school track and field meet, you are almost guaranteed to see a triple jumper who has too much height in their first phase. The result of this is often having a nonexistent second phase because the jumper is unable to handle the forces present when being pulled back to earth at 9.8 m/s2. This is almost always detrimental to performance, but it’s also unsafe from a health perspective. In the triple jump, horizontal velocity is at its greatest during the first phase. The combination of excessive height and gravity pulling down combined with the greatest horizontal velocity can create forces too great for the body to handle.

The second reason hip displacement is important is because it places hip flexors of the takeoff leg on stretch. The elastic action that follows will be the primary contributor to the takeoff leg cycling through a full range of motion. In my experience, it is a mistake to cue the cycling action of the takeoff leg as it comes through. When athletes do this, they tend to overuse the hip flexors and abdominals to raise the leg, which tends to negatively impact posture. In other words, the athlete will feel like they are bringing their leg higher by rotating their torso forward.

Creating hip displacement in this manner is also extremely similar to what is required in hurdling, so it is logical for coaches to seek the hurdle/triple jump combo. The cues I use for takeoff in triple jump are the same as when I was coaching the hurdles. “Push through the big toe,” or “leave your foot on the board as long as possible,” tends to work for most athletes.

Asymmetric bounding or skipping is another option that can help athletes get a feel for a longer contact with the ground. In this drill, athletes will have an aggressive push off of one foot while executing an easy push off of the other. This will give them the feeling that they need. The aggressive push tends to leave the foot on the ground for a longer amount of time, which leads to greater hip displacement.

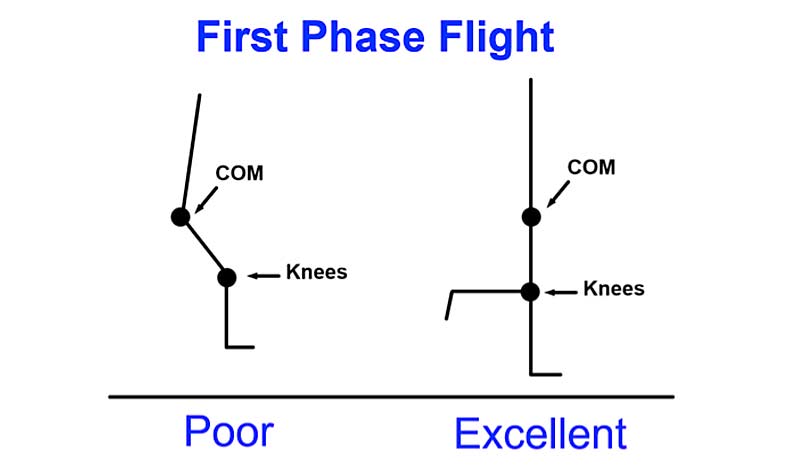

Moving along patiently allows athletes to develop quality motor patterns, so by the time they need to produce the significant power the event requires, they are able to do so without issue. Share on XThe most common error found among triple jumpers happens during first phase flight and involves failure to extend the swing (non-takeoff) leg. Air time during the first phase is just an extension of the gait cycle, and a step is actually happening in the air. If an athlete initiates the triple jump with their left leg, their right leg will go up, and while the athlete is airborne, the right leg should extend back down toward the ground, but not hit the ground. In essence, the left leg should be flexing while the right leg is extending, and the knee of each leg should meet under the athlete’s center of mass. The most common mistake is for the knees of athletes to meet in front of the center of mass. Athletes who fail to extend the swing leg will be unable to preserve posture.

The third issue of the first phase happens at its end and deals with the contact of the foot heading into the second phase. Ideally, the athlete should contact the ground in a heel-toe, rocking chair, or flat foot action. This helps disperse force and maintain momentum heading into the second phase. The mistake occurs when the athlete has a landing that is found more on the forefoot. What will happen with a forefoot landing is the heel will slam back into the ground, disrupting momentum and making it very difficult for the athlete to take advantage of any elastic qualities that would be present with a rolling contact. Instead of being one fluid motion moving forward, there is an impact, followed by a second impact, which makes the resulting motion more concentric in nature.

One reason this happens has already been addressed—excessive height in the first phase. If a person is suspended in air and feels threatened, the response is to find the ground with the forefoot. Think about walking down stairs, particularly in the dark. You lead with the forefoot so the body can find stability faster. The brain only cares about finding stability and surviving, it does not care about how far a person can triple jump! Therefore, a sound progression of escalating intensities of skipping, galloping, and bounding that emphasize the full-foot contact is imperative to get the brain to feel comfortable contacting the ground in that manner despite the extreme forces that will be present.

Flaw Correction

I am in constant pursuit of simplicity, and I have boiled down addressing these three issues into two drills with multiple variations. For the vast majority of the athletes I coach, I only ask them to focus on one item during the course of a drill. I have been fortunate to coach a few athletes who have been able to address multiple items within a rep, but that certainly is not the norm. Within each of these drills you will see a part-part-part whole approach.

Once again, the name of the game is patience, so do not feel the need to progress to a new variation until the athlete is ready or until it will help correct the issue they may be having. The beauty of these two drills is the scaffolding that can take place within each one. All triple jumpers can work on the same drill, so setting up is the same, but they will have a different focus within the drill.

The first drill is the athlete working the first phase and landing in the pit. Here, the athlete will jump off their left leg on the runway and land in the sand on that same leg. The focus of this first variation is hip displacement. All the jumper focuses on is creating quality hip displacement that puts the hip flexors on stretch and allows the jump leg to cycle through a nice range of motion before landing on it in the pit.

Once hip displacement is sound, the athlete can move onto the next subtlety, which is landing in the pit with their foot in a dorsiflexed position. Athletes may not be comfortable landing heel-toe in the sand, but I’m at least looking for a 90-degree angle between the foot and shin upon contact with the sand. If an athlete really struggles with hip displacement, it may be necessary to progress to this variation, so they do not develop the bad habit of landing on the forefoot upon completion of the first phase. Then the focus can shift back to hip displacement.

As a side note, and a reminder to myself, be sure to rake the sand between each rep! Athletes will feel more comfortable landing properly in flat sand, and this decreases the likelihood of tweaking an ankle.

The final application of the first drill is to focus on extension of the swing leg. This is often a difficult task for young athletes to master. For one, when done in a short approach style, they are not in the air very long, and they do not think they have time to cycle through a full extension. In many cases, this is correct, and athletes will compensate by having a higher-than-ideal takeoff. Here, a coach needs to prioritize. If the lack of swing leg extension is holding the triple jumper back, an excessive first phase is probably a worthwhile trade-off. To compensate, I would complex the drill with some skips for distance as a reminder to project horizontally.

If the lack of swing leg extension is holding the triple jumper back, an excessive first phase is probably a worthwhile trade-off, says @HFJumps. Share on XAll that being said, I have found a six- to eight-step approach works well for most athletes. To start with this variation, I simply ask the athlete to take a step in the air. This works for some, but not the majority. The next part of the intervention is to put a small (2- to 3-inch) box midway through the first phase and instruct the athlete to try to place the foot of their swing leg on top of the box. After the athlete gives you a crazy look, let them know that their foot will not contact the box—they just need to try to touch it.

Having this external target works wonders. When I first started using this method, I had athletes who struggled with this issue for months, and this fixed it in a day. While it may seem that I am setting up a rigid structure for this first drill, in practice it is really anything but that. It is extremely fluid, and we will progress and regress throughout the course of the season based on what we see in competition and in practice.

Videos 1-3. Examples of the phase one drill are shown with athletes of varying experience. The final clip shows an extension where the second phase is included.

The next drill is one I have stolen from the best young track coach I know, Joey Pacione. It emphasizes the three key actions from the previous drill, but in slow motion. Using hurdles is ideal due to their adjustable height, but anything that allows athletes to support themselves above the ground, and then come back in contact with the ground at the end, will work just fine. The main points of this drill are to:

- Get the athlete to execute a movement that creates hip displacement upon toe-off.

- Extend the swing leg—while supported by the arms on the hurdles so the legs are above the ground in the air.

- Come back in contact with the ground with a rolling or flat foot contact.

The strength of this drill is that its low intensity allows the athlete to complete it as much as they’d like to rehearse it. Once the athlete shows consistent competency, I often assign this for homework. To challenge their coordination, I instruct them to switch the sequence for half of the reps. So, if an athlete takes off with the right foot for 10 reps, I would like them to then do five additional reps where they take off with their left.

While this drill is excellent as a standalone, it becomes supercharged when it is paired with the first phase jump drill explained above. A common sequence in our practice is to have an athlete complete a first phase jump into the pit followed by a few cycles of the suspended first phase. Teaming these two drills together has increased athlete progress substantially. While I have no official data, I would say that what used to take 15 sessions can now be completed in three to five.

Video 4. Sometimes the best way to get better at something fast is to slow down.

Arm Action

When watching the 2012 Olympic final triple jump competition, you may have noticed athletes using a variety of arm styles. Although the trend seems to be heading toward double arm throughout on the men’s side, there are a variety of options available. Here’s my general advice:

- Do not instruct arm action initially. See how the athlete chooses to solve the problem, and then make adjustments if needed.

- Consider the other events the athlete competes in. If the athlete is a high jumper and utilizes a double-arm style at takeoff, it makes sense to use that style for triple jump as well. If the athlete uses a single-arm style for high jump, I think an argument could be made either way for triple. If the athlete also long jumps, where a single-arm style is almost always used, it may make sense to utilize that with triple jump. If an athlete is a hurdler, a single-arm style makes sense.

- Of course, these are not absolute. I have had many single-arm long jumpers use a double-arm style for triple. The disadvantage of this style is having to toggle back and forth between two different arm actions toward the end of the approach. This can be a challenge for athletes. Athletes who have the ability to toggle back and forth between these two distinct styles at a high speed tend to have a high degree of athleticism.

- If you have an athlete who is extremely adaptable and coordinated, this should not pose too much of a challenge. However, if you have an athlete who has less coordination, I would focus on keeping the arm styles the same. For those interested in ways to address this issue in practice with skipping, galloping, and run-run-jumps, consider purchasing “Jump Drills for All Athletes.”

- Overall, the number of permutations of arm action/style is too exhaustive to list. The 2012 video showcases quite a few different options. In general, I would advise to go with what the athlete does naturally. Ideally, there will be a correspondence with the other events the athlete completes, or the athlete will have the athleticism to toggle between styles.

That being said, do not be afraid to switch styles if what they do naturally is not showcasing progress. Many coaches have stories of 2- to 3-foot improvements shortly after athletes switched arm styles. To help young athletes gain the confidence to make this transition, expose them to different arm styles in skipping, galloping, and bounding. This is a simple way to enhance global athleticism. Patient coaches may not get the immediate impact that a narrow-minded coach achieves, but they will reap the rewards of a long-term philosophy when coordination and power capabilities synergize, leading an athlete to huge PRs!

Number Line Philosophy

An analogy I have used for triple jump philosophy is to refer to the number line. The most amazing part of triple jump is the “Matrix”-like hovering that elite athletes achieve in the second phase, but in order for an aspiring athlete to be able to hover like Neo in phase two, sprint mechanics (ground zero) and an effective first phase are essential. Invest in the ABCs, and see big returns in phases one, two, and three!

Since you’re here…

…we have a small favor to ask. More people are reading SimpliFaster than ever, and each week we bring you compelling content from coaches, sport scientists, and physiotherapists who are devoted to building better athletes. Please take a moment to share the articles on social media, engage the authors with questions and comments below, and link to articles when appropriate if you have a blog or participate on forums of related topics. — SF