Volleyball is a sport that requires several different levels of physical skills, including speed, power, change of direction, agility, and strength as well as the ability to repeat those movements. In order to play the sport at a high level, skills aside, you need to have a training plan in the off-season to develop each of these qualities.

In the article below, I’ll show you how to map out a training program, both sprinting and lifting, including examples of programs I have used over my six years training volleyball players.

Warmup and Observation

Before I get into the main focus of the workout, I want to quickly go over what I have coined the Ignition Series. We start each lift with some variation of the following:

-

- Breathing Drills/Reflexive Performance Reset

-

- Spring Ankle Concepts/Foot Activation

-

- Marches/Skips/Prances

-

- High Knees

There is nothing groundbreaking here, but I found following this outline prepared my athletes for the activities ahead better than any traditional dynamic warmup has. Not only do I think it’s a great series to improve performance, but you can learn a lot just by observing an athlete during these exercises.

I look to see how fluid the athlete moves during all these exercises as being able to observe athlete movement is one of the best assessments we have. It is skill to be able to relax during movement, so we put a big emphasis on this during this period.

Being able to observe athlete movement is one of the best assessments we have. It is skill to be able to relax during movement, says @bigk28. Share on XAnother important movement I am looking for is dorsiflexion of the foot when the foot comes up from striking the ground. It is a bad habit that when the knee comes up to have the foot in an improper position (inactive foot). The athlete loses a lot of the power of having that foot dorsiflexed ready to rapidly attack the ground. Keep an eye on this because this is very common amongst all team sport athletes that I have worked with.

Other movements I am looking for from my athletes is for them to be actively punching the ground from the middle to front part of the foot. Way too often, I see athletes strike the ground with the heel, which is detrimental to improving speed.

Athletes need to be aggressive in all these movements and by teaching them to punch the ground as opposed to just lifting their knee, they will get a better training effect. Switch your dynamic warmup to the ignition series and you will see a significant change in your athlete’s readiness.

Video 1. A hurdle mobility routine is easy to do before a lift in order to prepare players for the movements scheduled. Pick a couple of movements, such as the ones in this video, and complete anywhere from 5 to 10 reps focusing on good postural positions.

Acceleration

Acceleration, power, and movement in short spaces are key in the sport of volleyball. When looking at acceleration training, look no further than Al Vermeil’s chart found in Carl Valle’s ‘Kinetics Manual’.

In this chart, Vermeil covers different exercises and their direct effects on different areas of sprinting. These are my following go-to exercises when looking to improve an athlete’s acceleration capabilities and the order I use them in when constructing a workout. As you will notice, they progress in a way that prepares the athlete for the highest-intensity activity:

- Med Ball Throws: There are so many variations to use, but I like anything where total body movement is being incorporated. My go-to med ball exercises are underhand backward, underhand forward, and push press, as well as anything rotational. As in warmups, you will see during med ball throws which of your athletes are violent in their movements. I teach my athletes to rapidly load and fire that ball as far as they can, like an approach jump during competition.

- Athletes that struggle with rapidly loading and concentrically firing will struggle with acceleration and those that can’t accelerate in volleyball will struggle. Even my strongest athletes have shown huge struggles with med ball exercises and I think this limits their overall ability to be strong at accelerating. I usually aim for two-to-three sets of four-to-five reps for all my med ball exercises.

- Plyometrics: To me, all plyometric work needs to have a theme. If acceleration and strength are your primary objectives, use the following parameters:

-

- Single or double leg

- Deep to middle position in a counter movement

- Pauses

- Weighted

-

- I like to use these drills when I am specifically working on acceleration development. I will, more times than not, pair an unweighted movement that has a pause with a loaded movement. Remember, the goal here is to improve strength levels that affect acceleration, so the load for the weighted movements should be significant.

Form should never take a hit, but by my calculations you should see greater than an 80% detriment if you are looking to affect acceleration. For instance, if an athlete has a 20-inch vertical, you will need to find a load where the athlete is jumping four inches or less. A common pairing I will choose is a two-second paused SL maximum-effort jump with trap bar jumps, for three sets of four reps.

- Resisted Sprints: There are several avenues to take with resisted sprinting, but the ones I enjoy the most are hill sprints and sled-resisted sprints. I like to make sure the players are well-rested between reps, so the goal is 100% effort the entire distance of the rep. That should be almost common sense if the goal is to improve acceleration, but more often than not I see coaches get frazzled because their athletes are standing around, and they turn what was supposed to be an acceleration-based workout into a conditioning session.

-

- When looking at sled work, I usually look to keep the sled weight range to 30% and below of the athlete’s bodyweight. I have seen with weighted sled sprints, athletes self-correct with their technique. If you have poor technique with a heavier resisted sled, you will struggle to move the load.

Always start with a lower amount of reps and weight and see how the athlete’s times are responding. I usually start in the six-rep range for 10-yard accelerations. As the weeks go on, I will add in more reps and start increasing the distance to 20 yards.

- Timed Accelerations: This should be a staple for everyone in their training, but you should constantly be timing your athletes in their 5/10/20-yard sprints. Not only does it make the athletes extremely competitive amongst one another, but it truly helps inspire people to give maximum effort. At the end of the day, no athlete wants to be the slow athlete.

- Outside of pure motivation, it gives you a great indication as a coach on how your training is impacting each athlete. If things are continuing to trend in the right direction, stick with the plan. Not everyone will improve their accelerations every single time you measure it, otherwise they would turn into Olympic-level sprinters. We are just looking for trends in the data so we can make changes to our program when necessary.

Video 2. Resisted sprints, including hill sprints, have a huge carryover to acceleration, particularly the first 5-10m (which is important for volleyball). Couple this with med ball work and a well rounded lifting program and you have the tools you need to improve acceleration.

Bottom line, although volleyball success has a huge part to do with skill and reactiveness, if you are proficient at acceleration and you have the prerequite skills, you will have a higher likelihood of success.

Maximum Velocity

I work with 23 different sports, and I have yet to find one where the fastest team doesn’t have a distinct advantage. Speed dominates in every sport and usually the teams that are the fastest are also compromised of the better athletes.

Even though acceleration plays king in the sport of volleyball, maximum velocity plays a huge role in the development of the athlete, says @bigk28. Share on XEven though acceleration plays king in the sport of volleyball, maximum velocity plays a huge role in the development of the athlete. When looking at designing a program for a volleyball player, you must include both acceleration and maximum velocity training.

Video 3. Although volleyball players will never be in a position where they are moving at max velocity, training max velocity still provides a ton of benefits that carry over to their sport. Using such tools as wickets and fly 10’s will help train and assess how your players’ max velocity is improving. In theory, if our max velocity is improving, so is our acceleration: a quality very important in the sport of volleyball.

I know many coaches that will say that if an athlete never hits maximum velocity in a game, they won’t waste the time working on it. I think there are several benefits of training at top speeds that will never be accomplished with acceleration-based work only. Three key factors as to why I think training maximum velocity is a necessity for all sports:

-

- The speed and forces the body produces at maximum velocity will never be matched during any other training stimulus. I know in Ken Clark’s research about forces at top speed, he said Olympic-level athletes hit somewhere in the range of five times their bodyweight. We must treat maximum velocity sprints as an exercise to improve athleticism.

-

- Research shows that sprinting at maximum velocity is the best exercise for hamstring health. The best availability is availability, so including maximum velocity sprints should be a staple when trying to keep your athletes healthy.

- A sprint done at maximum velocity requires rhythm, coordination, and relaxation; this is also true during other athletic movements. While this is anecdotal, I have rarely seen a high-functioning athlete whose body was in a constant state of stress and tension.

- Running a longer-distance sprint and working on body control and movements will carry over to relaxation during other athletic movements. This has just been my eye test and not something I have the research to back up but to me it makes a lot of sense that a more relaxed athlete makes for a more productive athlete.

When measuring peak velocity, I have seen one common trend: our volleyball athletes who performed the best in the Flying 10 also had the best acceleration scores, jumped the highest in both their vertical and broad jump tests, and showed the best repeated power scores during the Scandinavian Rebound Jump Test (looking at reactive strength index).

While some may think a Flying 10 isn’t the best test for acceleration-based athletes, it does give you another piece of the puzzle in terms of an athletic profile. I also believe it gives you another valuable piece of your assessment tool. If you have an athlete who has the fastest Flying 10 on the team but one of the worst acceleration/power profiles, acceleration work should probably be most of the focus. Here are a few of my go-to exercises when I am trying to improve our volleyball athletes’ peak velocity.

- Bounding: I consider bounding in the category of reactive-based plyometric; in other words, a plyometric where you are working on a brief load followed by an explosive movement with as little ground contact as possible, covering as much distance or height as possible.

-

- This is a higher-level movement so you might have to break it down into simpler movements such as skips or single movements before you progress to

- The good thing about bounding is that you can progress the sets, reps, and distance in order to elicit a different response. Some of my favorite bounding exercises include speed bounds, single leg bounds, bounds for distance, straight leg bounds etc. I would start with two sets of 20 yards of repetitions and progress from there.

- Wicket Sprints: This drill is traditionally used to improve the sprint mechanics with field sport or track athletes who hit peak speed frequently throughout their competition, but remember the goal for our purposes isn’t to improve technique at maximum velocity, but rather to help improve the top speed we move at. Moving at a faster speed means we are putting more force into the ground, meaning we will have a greater carryover to other athletic movements.

-

- You don’t have to look cool and use actual hurdles; simply use cones and have athletes run on the side if they aren’t fit exactly to their stride length. You want a one-size-fits-all approach when it comes to wickets, otherwise you will spend an obscene amount of time figuring out individual wicket differences.

I like to do wicket sprints with cones mapped out for acceleration as well, since most athletes struggle with technical cues during acceleration. You are killing two birds with one stone when you have the athletes giving maximum effort and practicing good sprint habits for both acceleration and maximum velocity.

-

- In and Out’s: This drill is accomplished by having your athletes sprint to maximum velocity, followed by a distance with a drop in the intensity, then an increase in intensity over another distance. Again, not directly relatable to the sport itself, but I believe that by improving maximum velocity we are improving qualities that will carry over specifically to the sport of volleyball.

- Timed Maximum Velocity Sprints: This is the same concept as the above-mentioned timed sprints in acceleration. Time your sprints, relay the scores, and rank your athletes amongst one another. Athletes love feedback and want to know where they stand. Once again they aren’t going to hit PR’s every workout, but over time you should see progress.

I know some coaches love the term “sport specificity,” but to me, anything that will positively impact the physical attributes of my players is beneficial.

I know some coaches love the term *sport specificity,* but to me, anything that will positively impact the physical attributes of my players is beneficial, says @bigk28. Share on XThere is a huge correlation between maximum velocity and other characteristics that are related to volleyball. I have seen athletes improve their Fly 10 time, while simultaneously improving their strength levels, vertical jump, reactive strength index, and repeated broad jump.

We must use maximum velocity as another training stimulus: if you are taking out said stimulus, you are limiting the ceiling on the players’ athletic development.

Conditioning

I believe a majority of your “playing shape” preparation should come from high-intensity practice. However, that doesn’t mean that you should completely neglect the aerobic/repeat alactic quality.

I read years ago in Buddy Morris’s book on football preparation that football is primarily driven by two systems: aerobic and alactic. I believe volleyball is very similar. Buddy’s description gives you a very simplistic approach for a very complicated and intertwining system.

Video 4. Constantly be re-assessing your athletes and determining where the program needs to be tailored to fit their specific needs. The contract grid, by Musclelab, is one of the best jump tools out there and allows you to measure all types of jumps. While the regular vertical jump provides value on improvements in vertical power, the Scandanvian Rebound Jump Test gives you a bunch of data including reactive strength index (RSI).

The alactic system controls the jumps, accelerations, and all fast-moving actions, while the aerobic system feeds in the recovery of that system so athletes can repeat those actions over and over again. Here are some of my go-to modalities for conditioning the volleyball athlete:

- Tempo Runs: There are many benefits for tempo runs, including working on running efficiency, but for the purpose of this article, I think it helps develop an aerobic base. Tempo runs are exactly what they sound like; runs done at 70-75% intensity with the main goal being to build a base before moving on to other higher-intensity movements. I am still preaching good sprint mechanics—upright body position, foot strike under the body, good arm action, and neutral head position—but the main goal is to accumulate volume over the weeks of training.

-

- Some sports will do longer tempos, but I don’t believe it is necessary for volleyball to go over 50 meters (or midfield on a normal football field) per rep in their tempo runs. I follow each tempo run rep with a 50 meter recovery walk.

The rest here should not be overlooked; volleyball is a fast-moving sport with little recovery (somewhere from 16 to 20 seconds). The ability to recover faster than your opponent is a critical one. In between reps, I tell the athletes to focus on their breathing to bring their body back to a state of calm. I’ll start at 1200-1400 meters and make my way up to 1800-2000 meters total per workout.

- Lifting Circuits: These are pretty general circuits where am I having my athletes working with less than 50% load (I just tell to them to pick a relatively easy load) and perform for three-to-four sets of maximum repetitions in 30 seconds.

- I will always start with a lower body movement to start the workout (5-10 rep range depending on the day and movement), followed by an Olympic movement used to reinforce good positioning before the circuit. I usually pair the following exercises to make a tri-set circuit: upper body push, upper body pull, and accessory.

- EDT Lifting Circuits: The best description I’ve heard of EDT circuits from Cal Dietz is that they are designed to condition power sport athletes. That is exactly how I utilize them with my volleyball athletes. I usually pick three primary movements from this set: squat/deadlift, clean/snatch, and dumbbell horizontal/vertical push.

- I set the load at roughly 70-75% of our one-rep maximum and we go for a set amount of reps, performing singles of each exercise, trying to finish as fast as possible. I really love this to develop work capacity under load, or as a reload day following a central nervous system high/low routine. I have seen athletes significantly improve their work capacity by doing this type of workout two times a week.

Strength Training

Strength training has a huge impact in three main areas: setting the foundation for training other qualities, health and resiliency, and mass-specific force.

Strength has a huge carryover to acceleration, which tells me that my volleyball athletes need to be strong. My parameters for strength include loads heavier than 85% or less than .4-.5 m/s, depending on your athlete.

We spend a good part of the off-season working on strength. If your athletes aren’t strong, you are asking for trouble when they reach the demanding in-season schedule. My athletes usually play three games per week, and with that workload you are risking injuries and declining performance.

I think this where the outline of your lifting program is of the utmost importance. A lot of coaches put a number in their head for where their athletes need their strength to be and for some, that number may never be achievable in their career. So coaches spend years chasing numbers that will never be obtained and in essence miss out on developing other qualities in their lifting program.

Coaches have also wrongly correlated improvement in strength numbers as a way to assess their programs’ effectiveness. There are several problems with this, especially if the coach doesn’t have the highest integrity when performing maximum testing with their strength-based lifts.

I know most of the time people just want the recipe, but the truth is, each athlete is so different, there is no generic plan I could give you. I could have an athlete that comes in with a strong training background, and with traditional strength development, and they might make little progress on their maximum strength.

However, if you have an athlete that has little training background, strength work will continue to develop them holistically as an athlete. It can take up to two years to develop a base of strength, but it can pay off in other ways.

For example, during this period of strength development, I have seen my athletes simultaneously improve their acceleration (10/20 yard sprint), change of direction and power output (vertical/broad jump).

For our off-season programming (far out from the season) we will have three general prep blocks (aerobic, lactate, anaerobic) followed by three maximum strength blocks. Again, with a more experienced athlete you may have to change the plan to address any deficiencies. With that being said, I believe all athletes need to build a base with general prep work as well as retrain the eccentric and isometric qualities. From there, you can start to design blocks specifically for your athlete’s needs.

With this general program outline, I have seen all physical qualities improve throughout the entire year. More importantly, we have seen virtually no games missed throughout the course of each season.

Once an athlete has become ‘strong enough’ you can make the lifts more specific to the qualities you want to impact. For example, I have seen full seasons where athletes do mostly speed work in the weight room to supplement our acceleration/speed work.

Video 5. Olympic lifts are effective for developing power, while teaching eccentric absorption and kinesthetic awareness. Don’t be afraid to go overhead with your athletes, as we get strong posterior development with movements like the snatch.

I think everyone still benefits from GPP, eccentric, and isometric work, but where you go after that depends on your athlete. These are the main movements we focus on throughout the year:

- Squat variation

- Deadlift variation

- Safety bar split squat

- Clean variation

- Snatch variation

- Bench variation

- Olympic push variations

The sport doesn’t limit the athlete, rather the history of each athlete should determine the restrictions of the program. There will be times when certain things may need to be restricted based on injuries or ailments, but if you are extremely limiting your athlete in the weight room, then I struggle to see how that athlete will stay healthy throughout the course of an entire year.

As I mentioned earlier, the best ability for an athlete is availability, and lifting plays a huge role in keeping your athletes healthy, especially in a sport with such repetitive upper- and lower-body movements. Not only does lifting play a huge role in reducing the risk of injury, it also sets the foundation for developing all other qualities. Bryan Mann once said, and I paraphrase, if you skip out on developing strength, you will limit the potential of developing all other qualities.

If you skip out on developing strength, you will limit the potential of developing all other qualities, says @bigk28. Share on XThe best read of my entire career has been The Triphasic Manual by Cal Dietz and Ben Peterson. It is scientifically backed with the rationale needed to make outstanding progress in the weight room. I have used it for the last several years and have seen nothing but incredible results with regards to strength, speed, and power in a timely manner with my athletes.

Cal talks about undulation, but with a slight twist. Instead of traditional undulation where the volume drops as the intensity increases, we switch the days and approaches to each day.

Athletes usually coming back from a long weekend and then aren’t at their prime, so they need what I call a ‘primer day,’ with a moderate load with some medium volume to ‘activate’ the body for the week. After the body goes through that primer day, it is ready for the heaviest load of the week with the lowest amount of volume. The last day of the week is reserved for the lowest load with the highest volume, giving the athletes 72 hours to recover before the next training.

With a beginner, you will experience progress no matter what program, but as your athlete becomes more experienced, they will need a more specific program. The program can be one of three blocks: strength, power, or speed. Depending on your assessment, you will see which one of these your athletes need the most and in what end of the spectrum they need to work on.

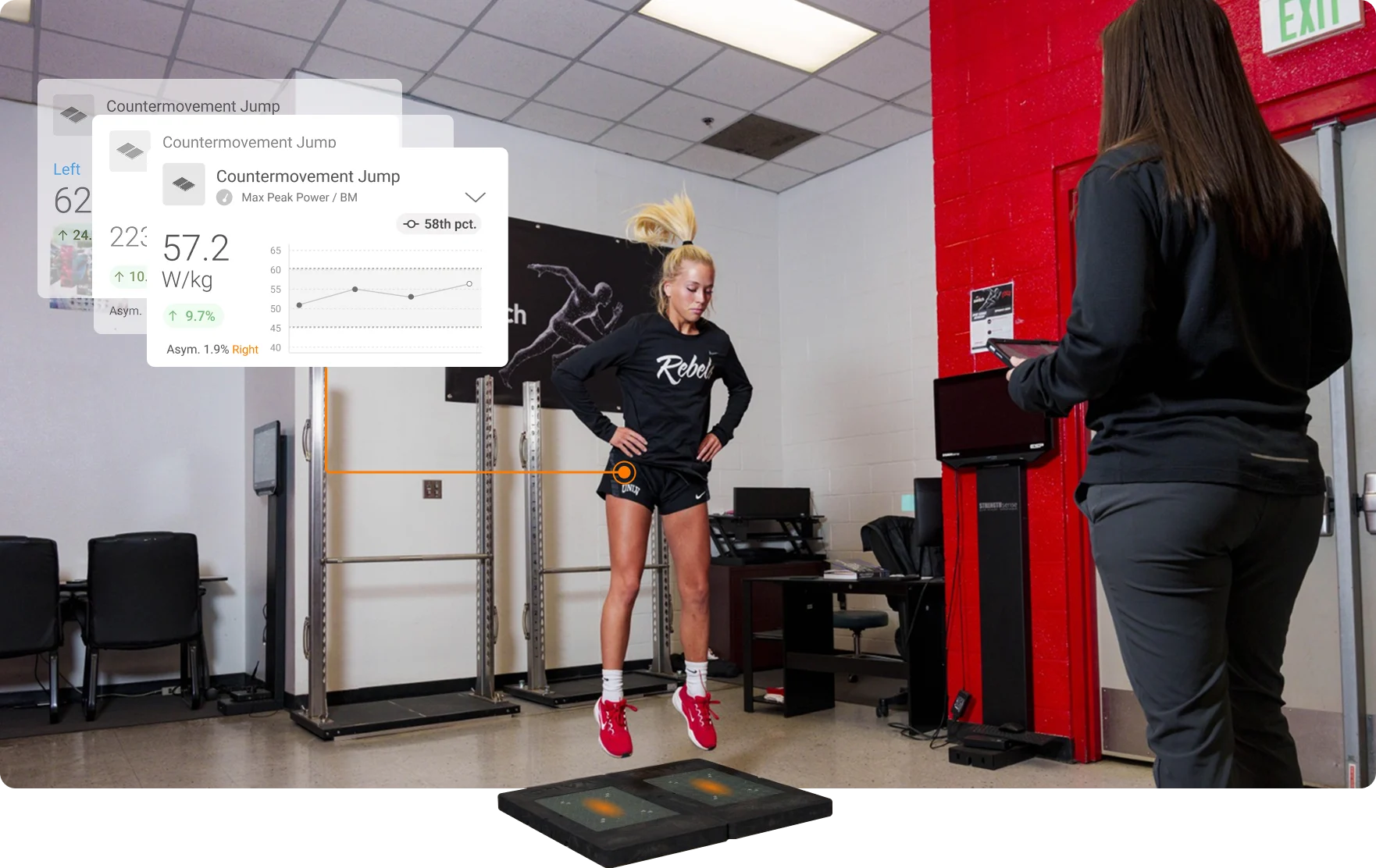

There are several methods to use, but I primarily use the 10/20 yard sprint as well as the countermovement jump vs. pause squat jump to see where my athletes need the specific focus. If I have a beginner athlete, they will progress through these qualities in order.

Video 6. Squats are a great tool to develop lower body strength in all athletes. If a player is new to training, you should continue to see improvements in power and speed as their squat continues to improve.

Each training block should have a specific theme. As Cal talks about, the body will respond better when it is presented with one specific stimulus (i.e. a training block dedicated to strength). Presenting the body with several different stimuli forces the body to adapt to them all at the same time, never really excelling at any.

Presenting the body with several different stimuli forces the body to adapt to them all at the same time, never really excelling at any, says @bigk28. Share on XServe and Hitting Speed

One of the more important metrics to assess and track with your volleyball program is serving speed. I labeled this section for both serve and hitting speed because if you train for a faster serving velocity, that will carry over to hitting. This is important because the team that has the faster serving speed will be the more challenging team to serve-receive against.

The speed reserve concept for sprinting comes into play here as well. Volleyball players may take anywhere from 60-120 swings in one given match. Not only is that a high volume of swings, but they usually must repeat this performance for several games spread throughout the week.

No matter how high your hitting speed, it will drop as the games start to pile up. Our off-season plan is to raise the ceiling on our hitting speed so we will still operate at a high level when we start to fatigue.

This test is relatively easy to perform. All you need is a radar gun. Personally, I use the Pocket Radar. I have the athletes perform five serves using their normal serve (standing float vs jump float vs topspin) with the radar gun positioned behind them. Only measure the serves that land in bounds as serves blasted at the back wall at high speeds are of little value.

Your lifting plan will have a big impact on how much serving speed will improve from year to year. I have seen serve speed improve by following a total body training protocol. I think it goes without saying that the more powerful you are the harder you will hit the ball, but a big factor of training I want to dive into further is training the upper body, a hotly-debated topic for overhead athletes.

Training the Upper Body

In my six years working with volleyball players, we have had ZERO upper body injuries. For an overhead sport, that is outstanding. Here are my go-to movements for developing the upper body, making your volleyball athletes more powerful and durable:

- Olympic Lifting: Olympic lifting has a strong carryover to acceleration, so we clean and snatch all year long with our volleyball athletes. Most of the work we do is singles, but if we are doing a teaching phase, we will go all the way up to four reps.

-

- I will not go into the specifics of the

benefits of Olympic lifting

- because the list is massive, but I believe we get good development of the upper back and posterior shoulder when performing the Olympic lifts year-round. Also, teaching the body to absorb a large amount of force eccentrically is something not many other exercises can do.

- Horizontal Pushing: Horizontal pushing is a staple movement we perform all year. Everything we do is low volume, one-to-three reps, depending on the emphasis of the block. There are no restrictions here. People often forget how important horizontal pressing (as well as vertical) is, not only for upper body strength and power, but also for stability of the shoulder overhead (i.e. serratus and pec complex). My go-to horizontal pushing exercises are:

-

- Barbell bench (regular, close grip, incline)

- Dumbbell bench (regular, floor press, incline)

- Pushups (weighted or unweighted)

- Medicine ball pushes

- Horizontal Pulling: You want your overhead athletes to be strong pullers. The rule of thumb I use is that whatever we are pressing, we should be able to at least pull the same load. If you want your athletes to stay healthy, you need a well-developed posterior chain and horizontal pulling will be a big weapon in your arsenal. My go-to horizontal pulling exercises are:

-

- Pendlay row

- Barbell row (pronated and supinated)

- Dumbbell row (standing and chest-supported)

- Cable row

- Vertical Pushing: We do vertical pushing exercises all year as well. We do primarily two vertical pushing exercises throughout the week: Olympic-based and strength-based. Volleyball is a sport that requires synchronization between the lower and upper body to perform movements at a high level. I think Olympic overhead movements check all these boxes. Use the same concept here as the other pressing movements—high loads and low volume. This is our overhead Olympic movement progression:

-

- Push press

- Power jerk

- Split jerk

- Vertical Pulling: As with horizontal presses and pulls, we will do a vertical push paired with a vertical pull. I like my athletes to do most of the work with a supinated or neutral grip in-season to relieve the stress on the shoulder, but in our off-season we do everything under the sun with regards to vertical pulling. Chin-ups are a staple throughout the year, and we aim to go from bodyweight to loaded for a low amount of reps. These are my staples for vertical pulling:

-

- Chin-ups

- Pull-ups

- Banded pull down

- Lat pull down

- Supinated lat pulldown

- Triceps/Biceps/Shoulder: When it comes to arm health, I believe the triceps, biceps, and shoulder play a huge role. However, I will not spend a ton of time programming to focus on these because I believe we hit a lot of these areas during our main movements. But if for some reason I feel like we need the accessory work, I will program any of the following:

-

- Dumbbell skull crusher

- Dumbbell hammer curl

- Dumbbell supinated curl

- Banded curl

- Banded overhead triceps extension

- Banded triceps extension

- Face pulls

- Band tears

- Reverse flys

- Banded shoulder series

Chasing Potential

Volleyball is an extremely versatile sport that requires a unique combination of speed, power, and strength. To maximize the potential of your volleyball athletes, you need a well-versed program that covers all areas that are required for success.

Train your athletes in both acceleration and peak velocity, as both will contribute to speed, rhythm and coordination on the court. Do not neglect the weight room, as strength sets the foundation of the house for all other athletic movements.

However, don’t be obsessed with chasing numbers. We are here to make the best volleyball athlete and it must be a fully encompassed program to accomplish such. If you follow the outline in this article, you will have the tools you need to maximize the potential of your athletes.

Since you’re here…

…we have a small favor to ask. More people are reading SimpliFaster than ever, and each week we bring you compelling content from coaches, sport scientists, and physiotherapists who are devoted to building better athletes. Please take a moment to share the articles on social media, engage the authors with questions and comments below, and link to articles when appropriate if you have a blog or participate on forums of related topics. — SF