My views on a plyometric program for a women’s volleyball team have shifted. I used to focus on improving jump height: the higher a player can jump, the better she will be. In line with that mindset, my methods emphasized having strong legs, improving coordination through better mechanics, and reducing ground contact time. And it worked—my athletes improved how high they could jump.

Except it didn’t seem to matter. I would have a player improve her jump height while not appearing to “play higher.” Furthermore, every season we had foot, ankle, and shin issues popping up with the players: tendonitis, stress reactions/fractures, plantar fasciitis, etc. But that’s volleyball. The sport involves a high volume of jumping and landing impacts, so there is going to be some strain on the soft tissue and joints. And these injuries are bound to happen, right?

Something wasn’t adding up.

This got me thinking about how I designed my plyo program for my athletes. I needed to reconfigure my plan so that I could still improve jump height but also reduce the risk of injury. I’ve been fortunate enough to work with a local positioning system (LPS) that allows us to have what can be described as an indoor satellite. The data we get gives us objective information on what our players are exposed to. Part of this dataset is a simple jump count, but more importantly, how high each jump is. I took a dive to see how often we’re jumping at maximal heights.

The Numbers

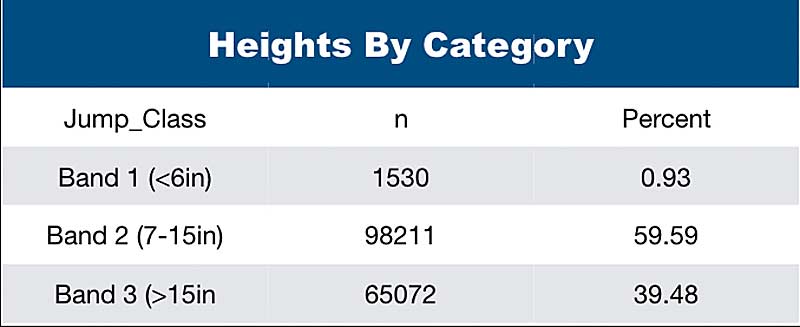

I pulled data from the last two seasons, which includes all practices and matches (I did not include Liberos and Defensive Specialists). I will note that, at Stanford, our back row players go through the same plyometric program as our front row players. For the sake of brevity, I find that being efficient at applying force into the ground not only makes you a better jumper but also probably a better athlete who is more efficient at covering ground. I find immense benefits for our back row players—at specific times of the year—to go through the same plyo program. Moving on, here is what we observed after pulling our data:

These numbers somewhat surprised me. As a non-volleyball player, I used to think of the sport as an outside hitter flying over the net and then bouncing balls right at the libero’s face. However, our data may tell a different story. As seen here, just under 40% of our total jumps fell into what I call “Band 3,” where jumps are max effort and are higher than 15 inches. Almost 60% of jumps fell in to “Band 2″—medium amplitude jumps between 7 and 15 inches. I found this very interesting, yet unfulfilling. And it got me thinking: are these ranges too big? Is 15 inches too high? Not high enough? I decided to take a deeper dive and adjusted my bands to 2-inch increments.

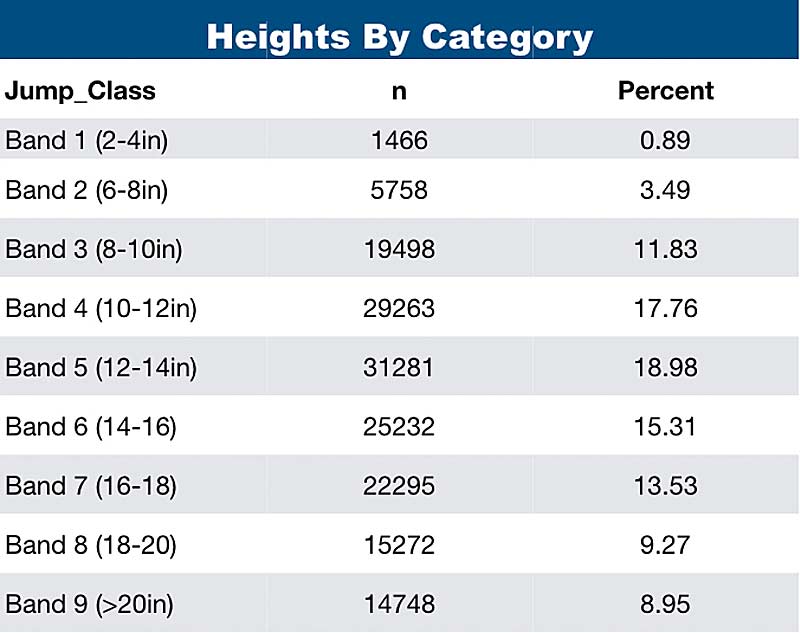

We can derive a few things from this data:

- Over a third (36.74%) of jumps are between Band 4 (10-12 inches) and Band 5 (12-14 inches).

- Almost two-thirds (63.88%) of jumps are at heights 8-16 inches (Bands 3-5).

- Ultimately, there is a large variety of jump heights.

This makes so much sense. While it’s fun to watch players fly over the net and crush volleyballs or stuff block an opponent, the reality is that volleyball isn’t played at these sky-high levels as often as one may think. The tempo of the set, the accuracy of a pass, and the setter’s ability to find their hitters are just some of the variables that affect the height at which a player will need to jump. Simply put, volleyball is a game of variability.

A volleyball athlete needs to not only be able to maximize their jump height but also jump effectively at lower heights and have the ability to perform these jumps repeatedly. I believe this is where the injuries start to creep in: the lower limbs get beat up with a high density of jumping volume. This volume is at all levels of intensity. We know that high amplitude jumps will have the most landing forces. Mixing that in with the repeated nature of the sport, landing on one leg—and landing not quite square—all factor into the potential for injury to occur. To improve performance and reduce injury, we need to answer a couple of questions:

- How do we train for the variability?

- Do we need to change the way we train altogether?

Prioritizing the Training

Let me be clear—just because we have a table of jump heights showing that volleyball may not be played as high as we think doesn’t mean it’s not important to improve max jump height. It most definitely is important. It also doesn’t mean that we need to focus solely on low intensity, repeated jumps.

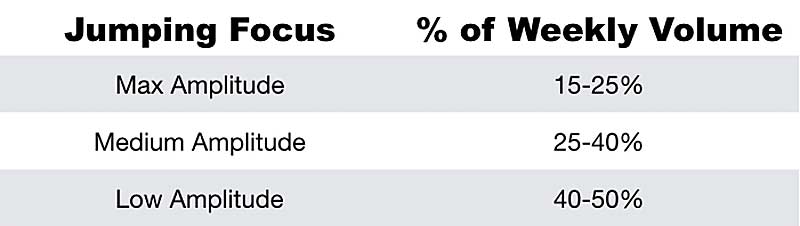

I suggest that we have an opportunity to train more effectively while improving jump height and reducing injury risk. The numbers we see offer a sightline to how we can best implement a plyometric training program. The goal is to blend improving performance and reducing injury. To help achieve this, we need to reprioritize jumping focus, specifically focusing on an uptick in low and moderate-intensity jumping. A weekly breakdown may look something like this:

First, let’s quickly define each focus.

- Max Amplitude

- Exactly what you’d think: max effort jumping. Countermove squat jumps, box jumps, full approach jumps, etc. Max amplitude jumping aims to get as high as possible. Broad jumps can also be categorized here. While they don’t achieve height, a max effort broad jump incorporates a very similar stimulus. These types of jumps also work on landing mechanics and help the lower body tissue adapt to high forces seen when landing.

- Medium Amplitude

- These are the jumps that fall into a gray area regarding effort and “how high.” I’ve found that a lot of unilateral jumping achieves a medium amplitude: split squat jumps, single-leg squat jumps, and skater hops. Other bilateral methods include repeated jump methods with an emphasis on speed and quickness off the ground and hurdle hops. I consider a medium amplitude jump to be one that happens when the jumping becomes repetitive, and we start sacrificing height for speed off the ground.

- Low Amplitude

- Jumps that are more focused on stiffness and reaction to the ground—pogos, jumping rope, etc. The idea is that we can crank on the volume and do something like this all day without having a major concern for injury.

By redistributing our jump volume, we may better match the jumping demands of the sport while reducing risk of injury. Let’s look at this through the lens of metabolic conditioning. Training at VO2max intensity is a very effective way to improve fitness. However, if we only trained at this high intensity, we would most certainly begin to accumulate fatigue quickly and thus increase our risk for a potential injury. Incorporating both low and moderate intensities in a weekly microcycle of conditioning provides significant benefit to our overall conditioning levels while reducing injury risk.

By having a solid mix among high, medium, and low intensity conditioning work, we can improve work capacity at levels where we do not accumulate as much fatigue and thus reduce the risk of injury. Let’s apply that same logic to plyometric training. Primarily training at max effort levels of jumping will undoubtedly help to improve how high our athletes can jump. However, this high exposure to high-velocity forces will also undoubtedly put our athletes at a higher risk of injury. Mixing in low and moderate jumps allows us to improve a skill and expose the tissue to a high volume of jumping. Exposing the tissue at low and moderate intensities reduces the risk of acute injury while allowing the tissue to adapt to jumping stress.

Sample Training Plan

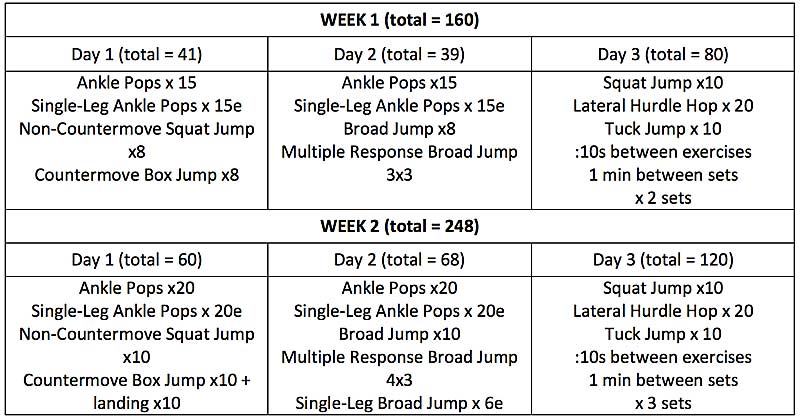

So let’s get right down to it. Below is an example of a 3-day plan where I’ve mapped out the first 2 weeks of what could easily be a 4-6 week plan. I will note that this is just an example and should not be copied and used verbatim in another setting. What’s not shown is a complimentary strength and conditioning program to partner with this plyometric program, which will undoubtedly affect how a plyometric program will look. That being said, the key takeaways here are:

- It is very simple to fluctuate jumping intensities

- We can achieve a very high volume of jumping on a weekly basis

As seen here, we can increase our total by almost 100 jumps between week one and week two. There is also a good mix of low, medium, and high intensity jumps—not only throughout the week but also within each day. With this mix, we can have higher jump exposures and fully ensure the athletes are warmed up and ready to jump.

Final Thoughts

I want to be clear: in the sport of volleyball, the need for maximal jump height is extremely important. My goal in writing this post is to highlight that training and jumping maximally is not the only method we need to use. Incorporating variability of jumping heights into a plyometric training component helps accommodate for the specificity of the sport while exposing the tissues to a high density of jump volume, thus resulting in more robust and resilient tissue. Also, a highly complementary strength and conditioning program is needed to help to maximize all training aspects you employ. Using a variety of plyometric training will undoubtedly enhance the training and performance of your volleyball athletes while keeping them healthy!

Since you’re here…

…we have a small favor to ask. More people are reading SimpliFaster than ever, and each week we bring you compelling content from coaches, sport scientists, and physiotherapists who are devoted to building better athletes. Please take a moment to share the articles on social media, engage the authors with questions and comments below, and link to articles when appropriate if you have a blog or participate on forums of related topics. — SF