One of the summer activities I have my cross-country runners do is throw a turbo-jav into a trash can. Since I give prizes for the winning toss, every time I do this my runners always want to take some warm-up tosses prior to competition. But are these warm-up tosses improving either their distance or their precision once competition begins?

A classic study from 1957 provides us with an insight on warming up for an activity similar to my “javelin in a can.” Forty-six male students were given a five-minute warmup and then instructed to throw a softball as far as they could. The participants came back a little more than a week later and, like my javelin toss, they would win prizes (in this case, money) if they could throw the softball farther than they did previously, but this time without benefit of a warmup. So, what happened? None of the participants threw farther than they had before.

Does this 60-year-old study suggest the inherent value of a warmup for any movement activity, or am I simply “lobbing a softball” to those who want to use this as evidence to corroborate why it makes sense to do some kind of warmup activity prior to competition?

What Is the Goal of Warmups?

It is a complicated answer because the concept of “warming up” means different things to different coaches. Is warming up stretching? Is it a combination of stretching with various movements? Is it mental rehearsal? Lighting up the central nervous system?

The concept of ‘warming up’ means different things to different coaches. Share on XMaybe it is all of these and more. But, if warmups are a smorgasbord of various activities with different purposes, do we need to fulfill all of these purposes in order for the warmup to be truly effective? The current debate on the value of static stretching is just one example of the confusion over which items from the warmup smorgasbord coaches and athletes need to put on their plates. That may depend on what specific physiological effect—as well as psychological effect—of warming up coaches most value, and there are many to choose from.

Is it muscle temperature? This makes sense since a temperature increase allows muscles to contract faster and with more fiber recruitment. For example, nerve impulses in people travel eight times more slowly than they do in frogs, which have much lower body temperatures. We know that a warmer muscle is likely to experience less damage, especially during eccentric contraction. Is it increased blood flow to the heart and muscles by way of movement that needs to be addressed? Might it be muscle plasticity?

Distance coaches will point out that a warmup results in increased oxygen and carbon dioxide exchange, and that a more-efficient oxygen transport means more available ATP. Others will contend that a warmup can reinforce important motor skills. I have always considered the warmup a valuable means to achieving competitive arousal. For example, Frank Shellock pointed out that a warmup leads to psychological increases in focus and attention, and that a warmup decreases the fear of injury.

We see examples of unique kinds of arousal techniques used in various sports. Football players will tap helmets together and punch down on shoulder pads, and boxers will glove their faces before the opening bell. Long jumper Mike Powell often slapped his face before taking off down the runway, and many sprinters still jump up and down a few times before backing into their blocks.

Others see the value of the warmup as a form of visualization—what Mel Siff used to describe as “imagineering.” You see this with wrestlers who jog around the mat as they mentally rehearse shooting for a takedown. Some athletes perform specific kinds of rehearsals right before a trial. Dwight Stones, for example, bobbed his head as he visualized his approach steps in the high jump. And there is some performance justification for suggesting that these activities are more than just ritual. Charles Duhigg described how, every night, Michael Phelps would play a mental recording of himself setting world records. Maxwell Maltz introduced this concept back in the early ’60s, and referred to it as “psycho-cybernetics,” the process of enhancing self-image through visualization and mental rehearsal.

Many elite coaches might also choose specific activities in a warmup because they intend to use them to spot any imbalances. In this case, the warmup might be considered a kind of movement screening. This makes sense, since most coaches and trainers say that the key goal of the warmup is to ward against potential injury, while at the same time getting athletes ready to compete.

But some warmup activities make more sense than others. I know cross-country and track coaches who have their runners jog a couple of laps or even a mile, then have them plop down on the turf or track to do 20 minutes of old-school static stretches, with each of those stretches held to a 10-count by the group leader. They then have those runners get back up and run another lap or two because they don’t quite trust that they are ready to race, or because they want to re-elevate things like core muscle temperature and blood pressure, both of which dropped back down during the static stretching. Some say they do this because they want their runners to “re-break a sweat.” Is the value of this approach more about its team bonding and ritual aspect?

I have always liked what Loren Seagrave and Kevin O’Donnell referred to as the “big warmup,” and many coaches include those activities in their pre-competition protocol. I like incorporating various kinds of skipping, hopping, or galloping done forward, backward, and laterally, and it’s extensive enough be its own workout. These kinds of activities seem to accomplish many different things, including elevating the temperature and blood pressure, and challenging runners neurologically. Additionally, since the group must duplicate the speed and amplitude of the group leader’s movements, athletes need to concentrate and stay focused. The activities I select are what I call “gravity constant,” emphasizing such things as timing, core stiffness, coordination, and reactivity.

Video 1: I like incorporating various kinds of skipping, hopping, or galloping done in all directions—forward, backward, and laterally—into warmups, and it’s extensive enough to be its own workout. Here, an athlete engages in complex rope skipping in all directions.

Video 2: In group warmups, the groups must duplicate the speed and amplitude of the group leader’s movements, forcing each athlete to concentrate and stay focused. I select what I call “gravity constant” activities, which emphasize such things as timing, core stiffness, coordination, and reactivity.

The Inclusion of Self-Massage Activities

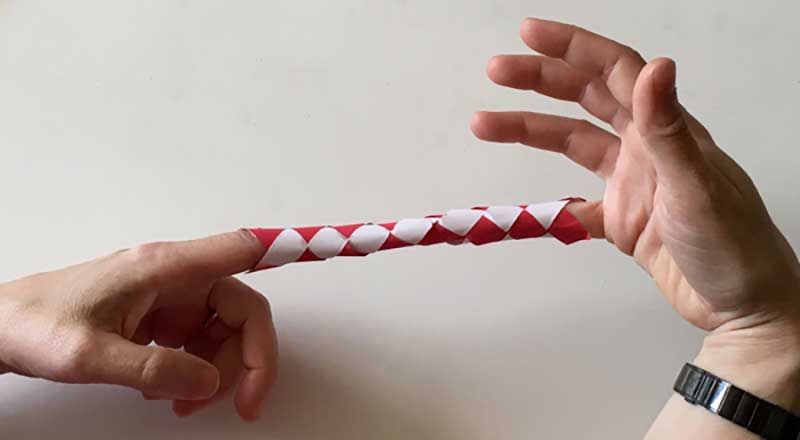

In recent years, the warmup has involved activities for removing tissue micro-trauma from previous training sessions. Trainers often describe small “hot spots” or knots in muscles as trigger points. They no longer try to remove these knots by way of conventional stretching, believing that if these trigger points are indeed like knots, pulling on the ends of the knot via conventional stretching only further tightens them—kind of like the old Chinese finger trap.

So, a form of self-massage has evolved. Again, at first this seems like nothing new, since the massage stick—which I used to describe as a rolling pin with bicycle handles on the ends—goes back more than 30 years.

Perhaps that stick, refined over the years by way of soft rubber knobs and waffles replacing the original hard plastic rings, will be viewed in a whole new way, thanks to Ben Affleck’s self-massage technique in the film, “The Accountant.”

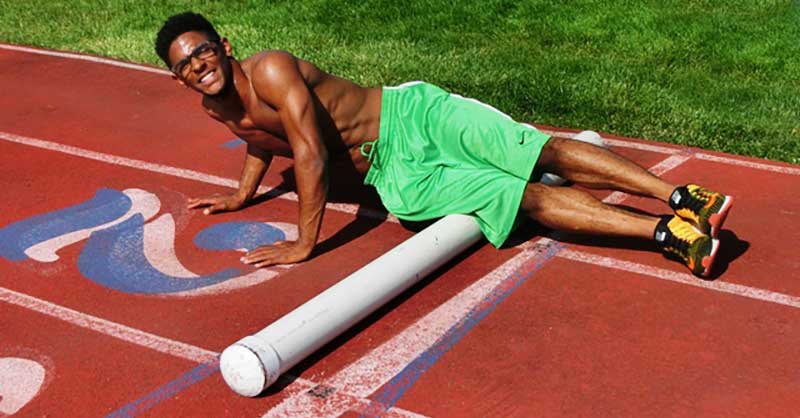

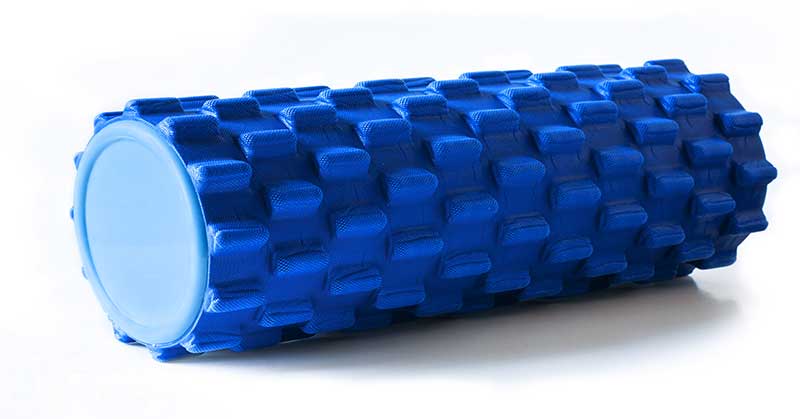

The theory is that rolling applies pressure to tissue sore spots in the muscle, thereby breaking up scar tissue and adhesions, and thus releasing the trigger points. In this regard, the stick has now evolved to tubes—the original being just sections of PVC soil pipe—but now these tubes consist of various configurations of denser foam. These new massage tubes are now very popular.

The technique used with these foam tubes has a technical name—SMR or Self-Myofascial Release. These rolling techniques increase both flexibility and range of motion through “autogenic inhibition.” And what does that mean? The tension the roller puts on the muscle causes the brain to relax that muscle to prevent it from tearing.

Trainers and therapists often progress to using tennis balls or lacrosse balls to target deeper trigger points, especially those in the back. There is no end to the therapist’s creativity here. Some tape these balls together to form what they call “massage peanuts.”

It Comes Down to a Matter of Taste

So, not only is the warmup a smorgasbord of choices, it also appears that even choices we make continue to undergo changes. I very much agree with Rett Larson, project manager for EXOS- China, who said that the “concept of the warmup needs to shift from simply focusing on the muscles of the body to embracing the multi-factorial nature of pre-training or competition preparation.”

The takeaway from all of this is that many techniques can activate muscles before training. Whatever coaches choose to implement in their warmup, what they are actually accomplishing may be the kind of neurological arousal that they believe best prepares their athletes for the demands of the sport or event they are competing in.

Coaches choose warmups they like through experience, but not everyone has the same experience. Share on XLike a smorgasbord, we can sample a variety of warmup routines, but whatever we choose to maintain is really the result of an “acquired taste” for what we think works best. These are activities we come to like through experience, but keep in mind that they reflect an appreciation that others might not share if they have not had similar experiences with the athletes they train.

Since you’re here…

…we have a small favor to ask. More people are reading SimpliFaster than ever, and each week we bring you compelling content from coaches, sport scientists, and physiotherapists who are devoted to building better athletes. Please take a moment to share the articles on social media, engage the authors with questions and comments below, and link to articles when appropriate if you have a blog or participate on forums of related topics. — SF

References

Duhigg, Charles. The Power of Habit: Why We Do What We Do and How to Change. London: Random House, 2013. Print.

Joyce, David, and Daniel Lewindon. High-performance Training for Sports. Leeds: Human Kinetics, 2014. Print

Maltz, Maxwell. Psycho-cybernetics. New York: TarcherPerigee, an Imprint of Penguin, 2016. Print

Rochelle, R., E. Michael, and V. Skubic. 1957. “Effect of warm-up on softball throw for distance.” Research Quarterly, 28: 357363. 2.

Shellock, F.G. (1986) “Research Applications: Physiological, psychological, and injury prevention aspects of warm-up.” National Strength & Conditioning Association Journal: Vol. 8, No. 5, pp. 24-27.