There is a war currently happening in track and field: a conflict centered on tempo training for sport. I tend to position myself as a radical centrist on topics until I have had the chance to formulate a clear opinion that I am ready to defend. As a rule, I try not to rock the boat unless I am clear enough, in my opinion, and I think it can provide context for others to consider.

Today, I plant my flag firmly on the mountain of tempo training. For most of my coaching career, I have used some aspect of tempo training within my program. Tempo is often described as submaximal activities with incomplete rest. Typically, it is used to develop work capacity for a specific aspect of sport.

Recently, several popular coaches have crucified the use of tempo training as a legitimate training modality. These coaches believe in nothing but acceleration and maximal velocity work at all times. Any training outside these limited training options is, at best, a waste of time and, at worst, detrimental to the health of the athlete. Thus, tempo work is training non grata.

Interestingly enough, many elite high school, college, and pro training groups do some tempo work throughout their training plan. Colleagues like Australian 400m sprinter guru Mike Hurst, Hall of Fame and Baylor Coach Clyde Hart, and World Youth Record Holder Coach Sean Burris regularly use/used tempo. Now, I know what you are thinking— “Those are 400-meter specialist coaches.” I frequently hear that argument from people, but when making the point, they’re already beginning to admit tempo seems to work the longer you take the event. However, even if I concede to you the more extended sprint argument, how do you explain the Jamaican athletes doing submaximal work right now?

If you follow sub-10-second sprinter Julian Forte on his YouTube page, you’ll see him and training partner Asafa Powell (former 100m world record holder) doing submaximal work. You don’t have to look too far to find a rival Jamaican sprint camp that featured Usain Bolt doing similar work a few years back. Indeed, the arms race on the talented tiny island certainly would discredit tempo training if it meant a distinct advantage in outperforming other training groups. Instead, the opposite is true, and submaximal work is a part of their annual plan.

You may now be whispering about genetic freaks or special supplements covering up for inadequate training. To counteract the freak theory, I would point to our coaching tree locally. Numerous coaches have adopted our methods, with tempo being a key component with high school athletes in many different environments having similar success. Implementing the system has resulted in many state championships, individual state records, and All State medalists.

Many coaches may ask the question, “Can’t I get the benefits from tempo by doing other training to circumvent the need for it?” In a practical sense, the answer is “It all depends.” Different aspects of speed/special endurance, biomechanical drills, plyometrics, general endurance work, and strength training can do what tempo does. However, the adaptations would be spread over numerous sessions and units of training. The time needed to get that done could lead to sessions that are impractical.

Tempo allows you to target a session that better prepares the athlete for the other key workouts the rest of the weeks. Additionally, mixed stimuli can lead to mixed results or suppressed adaptations to goals of the other key workouts throughout the week. Most of the enemies of tempo are not just a one-item interest group. Instead, they have a very thorough set of ideals that lead to limits in many other methods.

Examples of these limitations include mandated days away from practice, short or no warm-ups, no suppleness training, extremely short practice times, intervals shorter than 250 meters regardless of event, and no weight room. So, in reality, if the coaches don’t do tempo, they likely don’t do many other training modalities either. This philosophy has been highlighted often here at SimpliFaster and many webinars during quarantine.

It is time to bring tempo back as a proper and useful option in every coach’s toolbox, says @SprintersCompen. Share on XObviously, a minimalist philosophy is an attractive option for new coaches or those who need to limit workload to attract athletes who might not be all in on the sport of track and field. As we mature in our coaching, many of us get better at understanding that context is key to deciphering the methods used by others and their legitimacy to a coach’s unique set of circumstances. Somehow, a few professionals in the world of athletics have taken tempo training out of context. It is time to bring tempo back as a proper and useful option in every coach’s toolbox.

The Importance of Developing Work Capacity

Properly designed tempo training can reduce the risks for a sprinter across their entire career. I know it can seem counterintuitive to think increasing loads of less than maximal work can protect an athlete’s health, but let’s ponder this for a moment in other sports besides track and field.

First, let’s look at football. Since the collective bargaining agreement that reduced training camp practice time on the field, both minor and serious injuries have been on the rise. How many of you have had a fantasy team remain physically intact throughout an entire year? It was a well-intentioned idea to reduce training camp sessions and their length by reducing workload, but clearly, it has trended in the opposite direction.

The same can be said for replacing the value of general fitness with that of “load management” in the NBA and MLB. Many strength and conditioning coaches are spending less and less time on the second part of their job description. What happened to the days of Michael Jordan, John Stockton, or Kareem Abdul-Jabbar, who started nearly every game and never got hurt? We now have many athletes playing basketball all year long in AAU leagues who never practice developing skills or work capacity to make it through an entire professional season. Now it’s becoming commonplace to sit out stars in games against the Knicks to rest for the postseason. Could you imagine Reggie Miller asking for that time off and missing the chance to make Spike Lee look foolish? Of course not.

As for the MLB, what about Bob Gibson? Would Gibby’s style and relentless mound persistence have been possible if the St. Louis Cardinals managed his pitch count? I believe they would have over-managed his pitches into an earlier career decline. He needed that time on the mound to feel strong, deliver sweet chin music, and be the most feared pitcher in the history of the game. Now they often pull pitchers artificially with less-talented middle relievers. Could you imagine asking Bob Gibson to step off the mound for a middle reliever? Yeah, me neither.

Now, what about track and field? Have you ever heard of Carl Lewis and Allison Felix? Know what they have in common? Lots of submaximal velocity training. Oh, yeah, and medals in four different Olympic Games in speed power events! Regardless of the sport, battle-tested resilience developed through training combined with an elite performer is where you find greatness.

Lactic Tolerance and Buffering

Tempo’s most commonly associated benefit is it can improve an athlete’s lactic tolerance and clearance. Tolerance certainly is essential in longer sprints like the 200, 400, 300/400H, 800, 4×200, 4×400, and 4×800. Research shows that once an athlete crosses the 40-second barrier under a maximal effort, they are no longer able to efficiently buffer the flood of waste that burns the legs. Improving an athlete’s ability to buffer this poison enables them to run faster for longer in a race. All other things being equal, this is the difference between medaling or making the final—or not.

As for lactic clearance in a high school or college championship setting, a sprinter must perform at a high level multiple times within a few hours. In some state championship settings, this can even be two events in a row. For example, in Missouri, the 100-meter dash is directly followed by the 4×200, so clearing waste becomes vital for high performance and injury prevention. Properly planned tempo training will follow an event-specific training session from the day before.

When pairing two days, you create an athlete who can handle two high-effort days. Planning your sessions with this in mind enables your athlete to perform at a high level multiple days in a row, which is necessary for nearly all championships that are more than one day of competition. We all have seen athletes look like gods on day one of a championship, only to come up short or injured in the finals because they have never seen sessions or meets where they must compete for multiple days in a row.

Having the fastest maximum velocity is essential, but if you get injured before the championship, it doesn’t matter. Think about the careers of Xavier Carter or Usain Bolt. One has a fast, individual personal best, and the other is the greatest legend in track and field—repeatable high performance and injury prevention matter.

The Advantages of Using Tempo

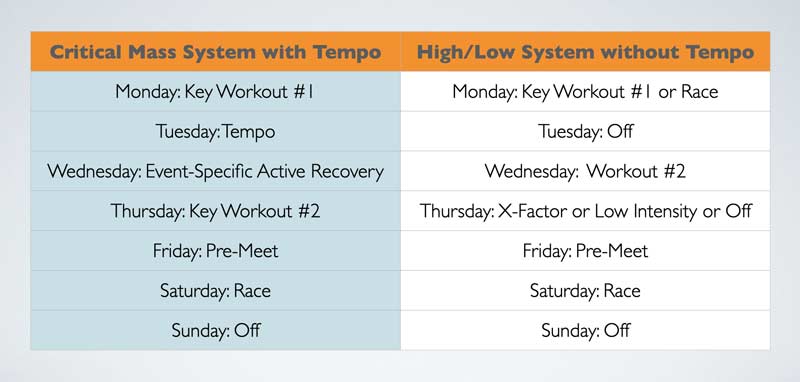

Doing some submaximal work helps get you to the finish line and perform your best when it matters most because it supports all the other work and restoration needed to complement your critical workouts. In a week with a race on Friday or Saturday, we only have one tempo session. Having at least one tempo day a week allows for an extra session every week for the season versus a strict high/low system that many minimal systems have within a microcycle. Throughout a typical 13-week high school season, this gives you nearly two more weeks of training sessions compared to a high/low program. When properly planned, this can go a long way to separating your athletes from the competition.

Additionally, weather can play a role where a maximal training session is impossible, especially in programs that nerf warm-ups that don’t “slow cook the meat.” Tempo allows for a safer option on inclement weather days when the surface or temperature makes training maximally very risky, thus giving your program more flexibility to pick the choice weather day of the week without just sending the athletes home. This will pay dividends mentally when athletes feel they can race in any weather because they have seen it in practice, albeit at a moderate intensity level.

Belief is the most powerful performance-enhancing drug. Coaches can use training back to back or in bad weather to help their athletes believe they are ready for the real challenges ahead that are typical in a spring sport. Additionally, slowing things down and adding some specific load gives a coach a chance to help the sprinter improve their mechanics in a less-intense environment so the sprinter learns the proper way to move. Eventually, they’ll be able to take those technical cues and spin them into a high velocity.

Tempo training also gives the body additional stimulus to improve slower adaptive connective tissues like tendons and ligaments and the skeletal system, which is not much different than the benefit of phasing in hypertrophic weight training in an annual strength training plan. Additionally, when it comes to ancillary activity, sprint coaches often love to use plyometrics due to their specificity being similar to running. However, tempo achieves a similar training effect and similar contact times. Still, it can repeat the loading at larger volumes and similar contact times while often being the safer option for athletes who might not be able to land or execute plyometrics correctly.

Tempo can also be used as a go-between to improve movement efficiency and impulse while an athlete acquires the skills to implement bounding or advanced plyometric menu items safely. The frequency of biomechanical action should improve the efficiency of the technique and robustness of an athlete. Moreover, one of the hidden ways tempo training can help a sprinter is through an improved circulatory system. Before he passed away, Charlie Francis discussed this with speed coach Derek Hansen as one of the hidden secrets to tempo training.

Charlie Francis said that one of the hidden secrets of tempo training was that it could help a sprinter by improving their circulatory system, says @SprintersCompen. Share on XObviously, lengthy general aerobic work based on distance training is a non-starter for most sprinters. However, tempo is often a bridge between anaerobic and aerobic. How does an improved circulatory system keep you from getting hurt? An athlete with a warmer body that can move in blood and move out waste has enormous advantages over someone with a system that’s not as efficient. Furthermore, think about how much an improved circulatory system can help an athlete who regularly competes in colder climates or rainy conditions like in the Northern United States, Canada, and Europe.

Implementing Tempo for Sprinters in Practice

Tempo work has become a large part of many top-quality sprinter programs around the world. A sprint coach can use either intensive or extensive tempo training. Extensive tempo is part of programs like Charlie Francis’s bipolar system and Clyde Hart’s long-to-short periodization models. Extensive tempo elicits different adaptations depending on the intensity of the intervals. Charlie Francis liked to train tempo workouts at 70% intensity to stimulate aerobic adaptations that he believed would add to the value of active recoveries.

Sean Burris, Nick Buckvar, and I used our tempos with 80-85% intensities. Our tempo work, in conjunction with short recoveries, creates waste and fatigue. However, we use these tempos to teach pacing for the second 200 meters in a 400-meter dash or 300/400H race. In addition to pacing, we choose to use these intensities because they allow the body to improve its buffering capacity. The buffering capacity comes from elevated sodium bicarbonate levels, enabling your athlete to push harder and longer.

Inexperienced coaches might look at these potential adaptations and try to extend the intervals. As a word of caution, sometimes more is not better. Long or lactic threshold runs are not ideal for short or mid sprinters. After a certain distance and with low intensities, there is an increased potential for poor posture and long ground contact times. Shorter distance tempo sprints allow for the athlete to still think about their running mechanics while at the same time maintaining a consistent pace. A sprinter who trains too slowly for too long adapts to the training, making them better at running slow for a long time. Not ideal for sprinting.

The other issue that comes from longer runs is psychological: A sprinter tends not to handle that type of training very well. A negative self-voice can be very destructive, and the longer a sprinter is out on a long run, the louder the voice becomes. Intervals on the track allow you to communicate with the sprinter to keep them appropriately motivated to finish the training.

Logistics and Communication

When performing tempo 200s, it is best to do your 200-meter work in the middle of the straightaways on the track, rather than a traditional full turn and the full straight. Since tempo workouts usually have short rest periods, this method gives the coach closer proximity to athletes by merely walking across the field. Crossing at mid-field helps the coach record accurate times without the need of an assistant to catch their finish, plus it gives them the advantage of frequent, clear communication with the sprinters as they run.

It also allows for emphasizing a critical area of every event—the finish. In finishing intervals, athletes come off the turn with only 50 meters left, and they only need to stay focused for a short period while they are fatigued. Therefore, with a shorter straightaway, they can concentrate on proper mechanics to help maintain their tempo and running form as they exit the turn for “home.” Simple cues such as “stay tall,” “hammer the arms,” and “short quick stride” will become ingrained in the sprinters every time they finish a race.

We typically choose to do our tempo work both clockwise and counterclockwise. I opted to reverse course to limit injuries from continually loading one side of our athlete’s bodies at high speed. If you are on an indoor track, it’s more important to go both ways, since the tight turns create significant centripetal force straining the body. It’s also best to train tempo in outside lanes in an indoor track environment to reduce the stress as much as possible. If you are doing 100 tempo repeats, you should still stand in the middle of the straightaways or athletic field. This way, you can cue your athletes to maintain proper posture.

Always remember, the rest periods are just as critical to the workout as the actual running intervals, says @SprintersCompen. Share on XEnsure your athletes do not fall on the ground or walk far away from their “go” mark. Sprinters falling down or wandering away from the go mark can disrupt the entire construction of the workout. If they don’t pay attention to their location, they can miss the proper recoveries that must be short to maintain the correct adaptations. Always remember, the rest periods are just as critical to the workout as the actual running intervals.

Used as a Cooldown

We frequently use decrescendo tempo 100-meter striders to cool down. We usually do 6-8 on the turf, starting fast at 90% and working our way down to 50%. We cut the intensity for each pair.

We have found that this format of a cooldown reduces our number of catastrophic calf muscle cramps at the end of the session. These cramps usually appear when you have your kids run two ugly laps around the track. Cramping often happens because you ask the athlete to load up extremely fatigued muscles that are being overloaded, and you don’t balance out the force demands from all the leg muscles in the posterior or anterior chain. When running these the athletes go barefoot on the turf, weather permitting.

Seasonal Progression of Tempo for Sprinters

Tempo must change as you move through the season as well. When we start the season, we use the previously mentioned percentages to guide our paces. As the season progresses, we use our tempos to simulate our comeback 200 on a 400-meter run. We run this after we establish a competition 400 or relay split.

The loads we start with are at the low end of the suggested volume. The volume moves higher as the athlete tolerates it for three weeks, with an unloading microcycle on the fourth. Rookies, untrained veterans, and trained veterans have different load progressions.

Once we get to six weeks away from the state championship, we begin the unloading phase. As we unload the tempo sessions, they transform in their purpose. They go from being tempo training to becoming a speed endurance session that backs up the previous Key Workout #1 on Monday. Besides unloading the volume, the recovery between reps enlarges, and the intensity slides up as well.

As we unload the tempo sessions, they transform in their purpose, says @SprintersCompen. Share on XThe implementation of changes coincides with our race schedule of single-day meets until we reach the state championship, typically a two-day competition unless storms play a factor. Back-to-back days of training while unloading volume to the overall plan provides a two-day experience that simulates a state meet schedule for our sprinters. It also takes the pressure off our athlete’s need to do anything later in the week before the season’s championship phase, when competing with fresh legs is of the utmost importance. I discuss these concepts in further detail here.

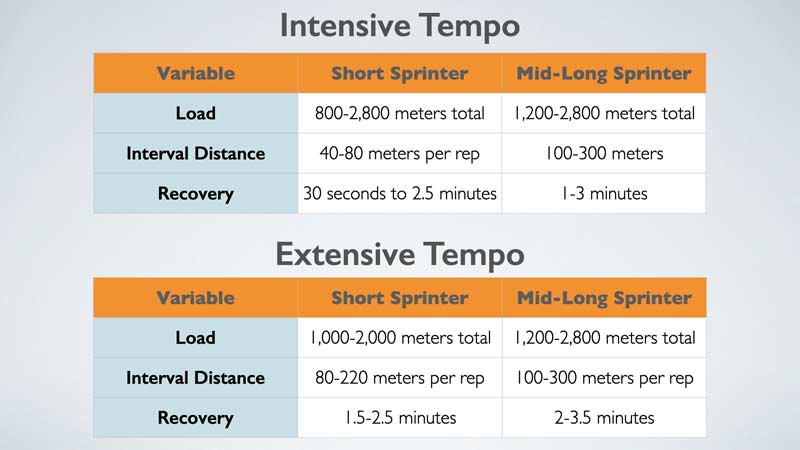

Interval Distance: The distances should be 80 meters or less (short sprinters). For extensive tempo distances, intervals should be between 100 and 200 meters (mid and long sprinters).

Recoveries: Intensive tempo recoveries between sets can be much larger because the shorter distances allow intensive intervals. These sets of intensive tempos are not just fatiguing aerobically and building waste, but they can trash a sprinter’s central nervous system (CNS). Understand the reality that multilayered fatigue recovery between sets can be much longer than extensive tempo training.

Recovery between intervals can be anywhere from 30 seconds up to five minutes if the athlete needs more time. However, to indeed be tempo, the rest should be concise and avoid longer recoveries. If they require more rest, I allow the sprinter’s recovery between interval sets to be more substantial and keep the athlete’s rest shorter between repetitions. Recovery between sets can be 3-10 minutes. Extensive tempo with 200-meter intervals recoveries can be from 45 seconds to two minutes.

I typically stay with two minutes until we reach the peak phase. During the peak phase, the theme of the repeat 200s changes by increasing the intensity, lengthening recovery, and changing volume. For the 100-meter intervals, your recoveries can be as short as 30 seconds up to 1.5 minutes. Recovery between sets with 100-meter tempo work can be up to two minutes.

Some coaches will choose to make the rest between these intervals active by adding a push-up, bodyweight squats, or other bodyweight activities to add stress between intervals. Another option for a long sprinter’s tempo recovery is to make it an active restoration with a 200-meter recovery run. Active recovery runs tend to be more commonly used by distance runners. Making the recoveries active will increase the difficulty of the work.

When using active recoveries, the sprinter should not run anywhere near the speeds they cover during the actual training interval. However, do not let the sprinter shuffle jog. The recovery run should never take longer than double the time it takes to complete the tempo interval.

Here is an example of a 400-meter hurdle tempo session I ran with NCAA D2 multi-event recorder holder Brent Vogel.

Load: Intensive tempo loads can be 800-2,800 meters. Extensive tempo loads can be quite large. Baylor Long to Short Sprint Coach Clyde Hart usually starts with the largest number of tempo repeats at the beginning of the season. In most club and high school programs, my suggestion is to begin with lower volumes. As the season progresses, a coach should add volume and then reduce the amount again when athletes reach their peak phase. Extensive volume for short sprinters is anywhere from 1,000-3,000 meters. For mid sprinters, the volume can be 1,800 to 3,000 meters. For long sprinters, the load can go from 1,800 to 4,000 meters.

Percentages and Placement of Tempo Training

You can justify all training. depending on the athlete’s sport, event group, environment, and genetic makeup. I know there have been many discussions (some heated) in some different forums about the percentage of effort for tempo work. Charlie Francis’s influence is evident on people who support the concept of keeping tempo percentage down to 70-75%. Coach Francis used these considerably lower intensities on tempo training to develop capillary beds to enhance the circulatory system for enhanced recovery and improved body temperature regulation. However, if you train at 85%, you teach the body to adapt by creating buffers to hold the performance-crushing waste product back for an increased amount of time.

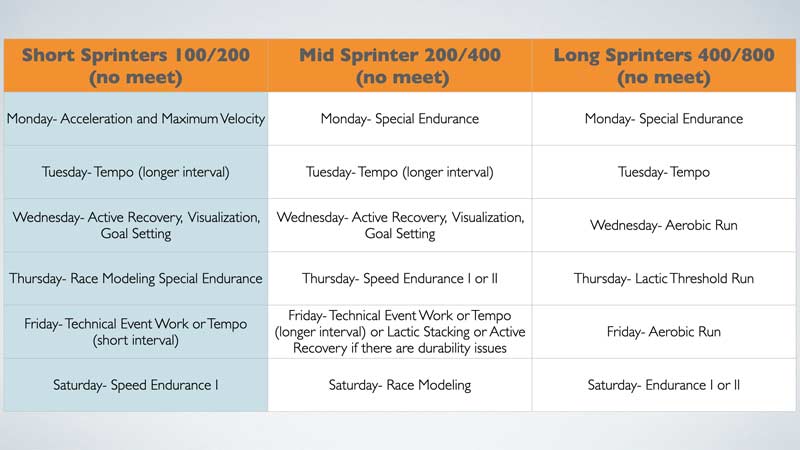

As stated earlier, your tempo training should hinge upon what event you are trying to train for as a competitor. I never put tempo training at the beginning of the week on Monday. The type of sprinter you are training will dictate what days and types of tempo will be the focus:

One of the most significant aspects of tempo workouts is that you will get something out of running at 70-75% or even 85%. Additionally, your sprinter can still maintain better mechanics in training tempo than pounding out aerobic work. Protecting the biomechanical model from the mid-range intensity is good, so they don’t learn lousy motor skills. Trudging through horrible workouts with no value is just a waste of time. Everything you do should have a purpose.

If the 400 is your event, you probably want to run faster during tempo training. If you have a 100-meter sprinter specialist who can bring their “A” game on “key workout” high-intensity days, lower-intensity tempo days are required. Lower-intensity tempo days for 100-meter specialists make sense due to the nervous system needing 48 hours to recover before it can provide you with the 95% effort necessary to achieve positive training effects for the highest-velocity sprints.

As previously stated, the themes I provided try to build in recovery for our sprinters depending on their strengths. If the weekly structure is too much for an athlete you are working with, I would move the weekly design to a 2/1/1/1/1 system. For example, a sprinter would be on a relatively heavy load for two days (Monday/Tuesday), off for one (Wednesday), on for one (Thursday), off for one (Friday), and on for one (Saturday).

Break Down the Walls

Remember, context is everything when developing a training plan. Those who live in absolutes lose themselves when defending something rigid like a brick—with enough force, it crumbles under the weight of reality. As it is difficult to know what the world will put in front of you, you must be flexible, or you will be unable to apply the best solution to common and uncommon problems alike.

Tempo training is a solution to some of the common challenges of athletic development. I have intended to provide insight as to why I still fly the flag of tempo training. When properly applied, it can improve biomechanics, race strategy, buffering capacity, and injury prevention; simulate championship conditions; and allow schedule flexibility in a training plan. Don’t automatically reject a common practice that has led to good results and progress because it doesn’t fit someone’s narrative.

Don’t let social media algorithms put you in a silo, unaware that the answers you seek for the athlete(s) you coach could be right on the other side of the wall, says @SprintersCompen. Share on XAs coaches, it’s important to challenge less-nuanced ideas respectfully. Constructive criticism is particularly vital if it is your friend, as you’re often one of the only ones they will listen too. Don’t let the social media algorithms put you in a silo, unaware that the answers you may seek for the athlete(s) you coach could be right on the other side of the wall.

Since you’re here…

…we have a small favor to ask. More people are reading SimpliFaster than ever, and each week we bring you compelling content from coaches, sport scientists, and physiotherapists who are devoted to building better athletes. Please take a moment to share the articles on social media, engage the authors with questions and comments below, and link to articles when appropriate if you have a blog or participate on forums of related topics. — SF