Early in my coaching career, I made an observation: The best coaches seemed to be those who talked the least while still getting what they wanted out of a group of athletes. These coaches acted like facilitators, guiding athletes through a well-thought-out session plan while allowing room for exploration and mistakes to happen. This is in stark contrast to the brand of coaches who make themselves heard throughout the entirety of a session or attempt to correct every possible movement error with extensive dialogue.

…the best coaches acted like facilitators, guiding athletes through a well-thought-out session plan while allowing room for exploration and mistakes to happen, says @CoachGies. Share on XSome of these coaches I observed didn’t necessarily have the most detailed knowledge of sport science, possess an endless library of drills to choose from, or concoct fabulously detailed technical explanations for every movement problem—but their athletes seemed to be very engaged, moved well, and succeeded in their sport. I soon realized that simply knowing all of the technical models and fixes to every drill or being the most vocal—while obviously useful at certain moments—is only one piece of a larger puzzle for improving athletic performance.

Based on my experience shadowing these coaches, I understood that I needed to learn how to engage athletes and improve their athletic abilities, while keeping my coaching feedback to the minimum necessary to push them forward.

From Beginner to Expert: How Do Athletes Become Great?

The ALTIS Virtual Apprentice Coach Program this past June was a fantastic learning experience. There were many great presenters, but Stu McMillan’s presentation on the “Art and Science of Speed for Team Sport” was particularly enlightening. He reminded me of some key models in motor learning that I had forgotten and introduced me to a few new ones. Some of these concepts included the Yerkes-Dodson Law, Newell’s three stages of learning, the challenge point framework, and how motor learning is embedded into our physical world. (For the sake of brevity, I will not dive into an explanation of each. However, I would encourage you to further explore these concepts.)

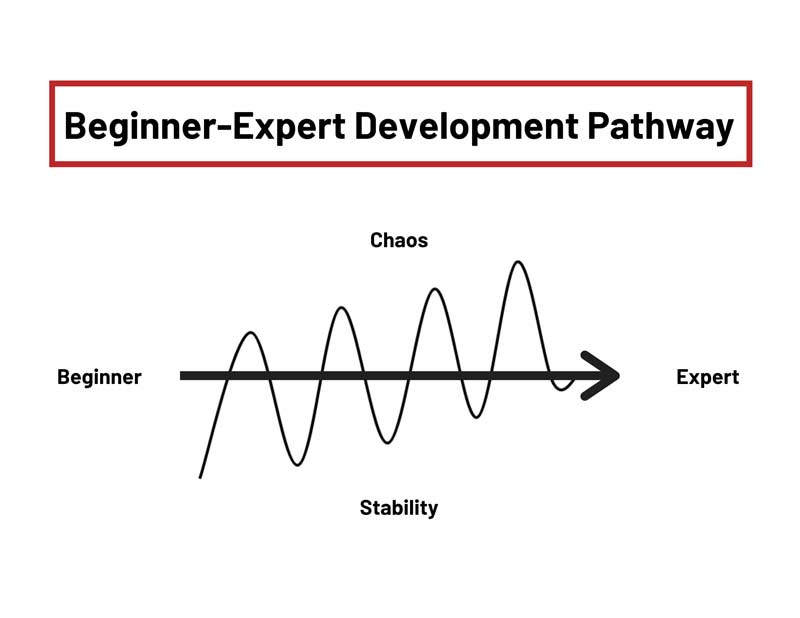

Now, in order for my simple brain to make sense of these concepts, I needed to come up with a straightforward way to view them. In essence, the previously mentioned motor learning models highlight what needs to happen as an athlete navigates the road toward expertise, or as I have conceptualized it, the Beginner-Expert Development Pathway (figure 1).

When learning a new skill, there need to be periods of stability to teach and solidify previous learning, as well as periods of chaos and uncertainty to challenge and expand learning. Share on XWhen learning a new skill, there need to be periods of stability to teach and solidify previous learning, as well as periods of chaos and uncertainty to challenge and expand learning. As an athlete’s skill set improves (moving toward expertise), the relative challenge of training elements should increase to stretch their abilities, while slightly reducing the frequency of stable and predictive elements, as the stimulus they provide diminishes as an athlete improves. A novice or developmental athlete needs to constantly navigate between stability and chaos to develop the physical, technical, tactical, and mental capacities necessary to successfully execute a specific task in a given environment.

The following are five key pillars that must occur to ensure an athlete moves along this pathway successfully:

- Pillar 1. If a drill is too comfortable, the athlete will become disengaged and no learning will take place. Conversely, if a drill is too challenging for their current abilities, the athlete will revert to what they are comfortable with and no exploration will take place. An optimal level of stimulation is needed so an athlete remains engaged while exploring new movement solutions.

- Pillar 2. The athlete needs enough time and exposure with a movement skill before it becomes automated.

- Pillar 3. Periodic manipulation of environmental constraints must occur to cause an athlete to adaptively detect and generate correct movement solutions.

- Pillar 4. The appropriate difficulty for a beginner would be inappropriate for an expert, and vice versa.

- Pillar 5. As an athlete gets better at perception-action (more stable), the task difficulty needs to increase (more chaotic).

My belief is that coaches who can implement these ideas effectively will be able to develop more skilled athletes in a wide variety of contexts…not just athletes proficient at a specific drill in training. These athletes will be able to successfully adapt and move in a wide variety of environments, which is ultimately what we want. However, I feel something gets lost in our profession among all of the articles and videos on new variations of drills, programming, and exercise selection: How do we actually coach an athlete through this process?

Coaching stable and predictable drills and exercises is fairly straightforward (notice I didn’t say easy!). Coaching the more chaotic elements while getting real development out of athletes, on the other hand, can be more difficult. This is what the coaches I was talking about at the beginning of this article did the best.

Fun and Games

In a previous article, I argued that a games-based approach (GBA) can be an effective tool in an S&C coach’s arsenal and explained how athletic development not only includes physical abilities, but tactical, technical, and mental components as well (i.e., the Four Coactive Model of Player Preparation from Dr. Fergus Connolly and Cameron Josse). The question now is: How the heck can I, an S&C coach, implement games to effectively drive athletic development? I don’t just want kids playing random games; I’ve got movement patterns to teach! And isn’t all that fluffy stuff the job of the sports coach?

Understanding the Utility of GBAs

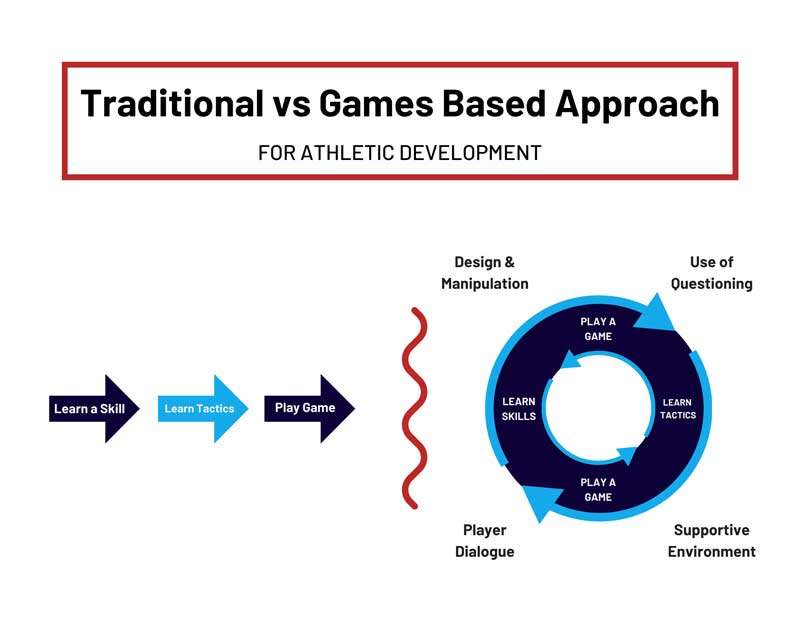

In traditional models of coaching,1 technique mastery is emphasized prior to game play. There is an emphasis on skill work in overly simplistic, pre-planned, and unpressurized situations that do not mimic the demands seen in a real game (sounds like some agility videos that go viral on social media). This will ultimately create a separation between technique and tactical knowledge, causing a disconnect between training and the game where players are not able to respond to relevant stimuli.

Video 1. “Partner Tag”: The pair needs to work together to get into position and pass the ball to get close enough to tag another player. (See Appendix below for full game rules.)

On the other hand, GBAs are an alternative means to contextualize learning within game-like activities (not to be confused with “free play,” although that can still be useful in certain instances). They were originally created to help PE teachers develop students’ tactical awareness to ultimately improve game performance. The coach acts more like a facilitator, using questions to promote player dialogue and reflection to guide the learning process….which was exactly what I saw in the best coaches I’ve observed!

The four common features of GBAs are:

- Design and manipulation of practice games/activities (emphasis added).

- Use of questioning.

- Opportunities of player dialogue.

- Building a supportive socio-moral environment.

The literature is also quite convincing in favor of GBAs, as highlighted by Kinnerk et al.’s review.1 It shows that in team sport environments, GBAs can improve tactical awareness and decision-making, while also increasing players’ affective domain development (the mental stuff, like emotions, feelings, and attitudes). If you’ve ever watched these types of games in action, you can see qualities such as anticipation, timing of runs, scanning, communication, energy system development, various starting positions, and short and long accelerations.

GBAs are fantastic opportunities to tie in multiple training elements for athletes to problem-solve, while increasing the transfer of your training programs to the sport itself.

Coaching GBAs

As we look at how to incorporate GBAs in an S&C setting, we should ask the question: What are we actually trying to achieve with our athletes?

In my opinion, we as performance coaches are trying to develop skilled athletes who can rapidly read and react to environmental triggers with the correct movement solution. We are looking to improve not only physical capacities, but the technical, tactical, and mental pieces that allow an athlete’s physical abilities to be used to full effect.

When deciding which games work best, there really are no hard and fast rules. There are endless possibilities, and I’d encourage you to just sit and think about tweaking classic games to incorporate specific skills you are trying to target. I try to come up with a new game, or at least slight rule changes to my favorite games, almost every week with my athletes. I am always assessing where my athletes are on the Beginner-Expert Development Pathway and determining whether I need to increase chaos or increase stability.

I’d encourage you to just sit and think about tweaking classic games to incorporate specific skills you are trying to target, says @CoachGies. Share on XVariations of tag or ball games, with added twists or rule changes to target specific developmental areas, often produce the best results. These can be included at the beginning or end of sessions in 10-minute blocks as a fun warm-up or a way to tie in the technical components of the session. You can also use GBAs as a conditioning component or use a game as the entire training session…the possibilities are limitless.

Some examples of ways to alter traditional games include:

- Team captains. When introducing a new game, designate team captains who are the only players you tell the rules to, and they then have to relay that information back to their respective teams. You can assess how good the athletes’ communication and listening skills are based on how well the teams are playing. If it isn’t very good, you can stop the game and chat about the importance of listening to instructions and then re-explain the rules to the captains. Usually the players are much more engaged the second time.

- Limit who can speak. Sometimes I only allow certain players to speak during the game (or else risk a point deduction). If there is an athlete who you want to see develop their communication skills or get more involved, this one works great. Conversely, if you have a particularly disruptive athlete, getting them not to talk and focus on body language works wonders.

- Unexpected points. As a game is being played, you can randomly award extra points for specific moves or skills, thereby causing kids to try those movements over and over. For example, three points instead of one if you score with your non-dominant leg during a small-sided soccer game.

- Players choosing rules. Get an athlete to come up with a rule. This can be loads of fun because it even surprises you and can get the kids to really buy in because they are involved with the session on a deeper level.

- Keeping track of your team’s points. This is a great one to make sure all players on a team are paying attention. A few minutes into a game, I’ll stop everyone and say “Everyone on Team A, shout out your score in 3, 2, 1!” and do the same for Team B. Often, several people won’t say anything (because they don’t know) or a few athletes will say different scores. Unless everyone on the team shouts the same score, I make them go back to zero. This gets the kids instantly tuned in because what kid wants to be the person costing the team all their points? As the game continues, players make sure they yell out the score and that their teammates are paying attention, and when I stop the game to ask the score again, they are discussing amongst themselves to ensure everyone is on the same page.

- Superpowers. Give a particular player an extra ability during a game. This could be extra points if they score, they are the only person who can run or shoot, or something wildly different. This is a fantastic option for a quieter player to get them more involved, or for a new athlete to the group, because it gets them involved straight away and others need to engage and talk with them. It will also get the players creating strategies on the fly around that player’s superpower.

- Special Bonuses. These are used as rewards to entice players to try new things. If they successfully execute a skill, they get a short-term bonus (e.g., point multiplier, run with the ball, etc.). You can also have it where if the team gets a certain number of points or passes, they get a particular superpower for a limited time (e.g., 20 seconds) before they lose it again. You can also use it for when an athlete successfully executes a particularly hard skill, the team gets a large amount of points or an automatic win (e.g., cross field kick in a rugby-style game).

- Multiple Levels. For each game you implement, have progressions and regressions. Once athletes master a particular level (or at least improve their consistency), add a new layer that pushes them along the Beginner-Expert Development Pathway.

- For example, if you are playing some sort of small-sided soccer game, you can add a level where if a player turns a ball over to the other team, they need to sprint 20 meters off the playing area to a randomly placed cone before they can enter the game again. This results in a few things: a momentary advantage for the other team to capitalize on, speed and fitness development for the player running to the cone and back (because they want to get back into the action), and more mental pressure on each player because they don’t want to turn the ball over so they need to improve their defensive skills and tactical abilities.

Notice how none of these examples center around how the athlete moves. Of course, you can address this when needed, but it is great to see athletes improve the way they move simply by changing the environmental constraints rather than through specific and direct coaching feedback. However, don’t simply add rules and leave it at that—to get the full effect from GBAs, we need to act as facilitators and use questioning and promote player dialogue. You need to ensure you step in at the right time and guide athletes to learn for themselves, while also stepping back and letting the athletes get on with it if you recognize they are being challenged appropriately.

It is great to see athletes improve the way they move simply by changing the environmental constraints rather than through specific and direct coaching feedback, says @CoachGies. Share on XSimilarly, you don’t need to over-coach and make the execution of the game “perfect,” as that could stunt the learning process. I try to stay as silent as possible (besides general encouragement) to see how athletes perform without constant coaching feedback. You’d be surprised how quickly an athlete improves simply through trial and error.

Video 2. “Cone Scramble” game. The player with the ball cannot step on a cone if another player is touching it. As they run around looking for free cones, the other players must work to cover up the cones. (See Appendix below for full game rules.)

When a rule is added, or you notice players struggling with a concept or skill, bring them in to talk about it. The key is to use open-ended questions and get players to guide their own learning process.

- “Ok, what’s going well/what’s going wrong?”

- “What do you think you could do differently to get a better result?”

- “What if you tried this? Do you think that would help? What else could you try?”

- “Johnny, you seemed to be getting frustrated. What’s the problem and what can we/you do about it?”

- “Jimmy, what are your thoughts/what do you think?”

- “Did you notice what happened when you implemented X? That was great! What else can we do to improve that result?”

By making players part of the problem-solving process, you will get more engagement, and the athletes will get better at working together. Often, I don’t even give a solution or correct them when they come up with something themselves—we just go with it and re-assess. Sometimes you will have to help them along a little more, especially with younger or more developmental athletes, but kids tend to be cleverer than we think. You can then see which athletes are more natural leaders and which ones might need more help in this area. Similarly, you can see which kids get overly frustrated or take it out on other players—then, you can have a private word or encourage them to be a better teammate and search for a solution rather than complaining.

When working with a group, I often implement the idea of “Start fast, finish fast”…similar to the concept of Play-Practice-Play. I tend to start a training session with a fast-paced GBA to get kids dialed in right away, spend the middle portion working on more traditional training (drills, linear sprints/jumps), and finish with another fast-paced GBA to contextualize the technical components while making sure kids leave excited and beg their parents to come back next week. Based on the intended outcomes of the session or the needs of the particular athlete(s), the activities and games I select will help me create the environment needed to develop those particular goals. During the middle of a session, I can spend time doing drills and more technical pieces to reinforce what I want out of the games, but this is much easier to do when the kids are excited and having fun throughout the session because of a fast start.

The possibilities are endless in terms of the games you can implement, and the key is guiding your athletes along the Beginner-Expert Development Pathway, with the game as a tool to achieve this. Now that I’ve (hopefully) justified the utility of GBAs in an S&C context, I’d like to share a particularly fun game I use regularly.

Chesty Ball

I often come up with silly names for the games we play. The city I’m based out of, Chestermere (Alberta, Canada), is the inspiration for the name Chesty Ball. It is a variation of basketball and can be played either full court or half court (or even smaller), but it is especially good when played on the mini courts at middle schools. We play with a volleyball, but any ball will do.

There are several levels for scoring points:

- One point for hitting any portion of the backboard

- Two points for getting it in the net.

- Five points for kicking it off the backboard.

- Minus one point for hitting just the rim or missing the backboard completely.

We introduce this game initially with no running with the ball (just pivoting) and turnovers only if the ball is intercepted or goes out of bounds. Once athletes understand the basics, we introduce running with the ball and other rules to speed up decision-making and gameplay. This scoring system allows players of all abilities the chance to score and contribute to the team’s success, as well as offering high-reward scoring options, but the point penalty for missing ensures players will still be strategic and not just try to kick the ball endlessly. Awesome game, especially when you add new scoring options and other rules.

As you can see, this game incorporates physical (fitness, linear and multidirectional accelerations, jumping), technical (passing, catching, throwing, body control), tactical (coming up with game plan, reacting to your own players and opponents, responding to new rule changes), and mental elements (composure, communication). More importantly, you don’t need to coach any particular element too much. You set the parameters of the game, implement various rules, and let the athletes go. You then facilitate learning through targeted questioning to ensure the goals of the session are being achieved. To me, this seems like the optimal environment to develop actual athletes, not just kids who can perform in the weight room or repeat a drill.

Final Questions to Ask Yourself

This article is not an attack on current coaching practices. My goal is to have you reflect on your own session plans and coaching behaviors during those sessions and ask:

- Do I include elements of GBAs?

- Do I spend periods of time being silent and simply watching?

- How often do I act as a facilitator?

Of course, you need to spend time breaking down skills and developing specific movement patterns in a controlled and stable environment. But by understanding the motor development process and how an athlete moves from a beginner to a skilled performer, you will understand the need for chaotic elements that challenge and stretch an athlete’s learning ability.

GBAs allow a coach to incorporate multiple components of athletic development while contextualizing learning into more realistic scenarios, says @CoachGies. Share on XGBAs allow a coach to incorporate multiple components of athletic development while contextualizing learning into more realistic scenarios. By acting as a facilitator, you will foster reflection and learning on a deeper level, while creating a fun and enjoyable experience for your athletes.

Appendix: Game Rules & Setup

- Partner Tag

- In a small box (8-10 meters per side), two players are working as a team to tag the rest of the players.

- To get someone out, one tagger must touch a player with a ball (ball needs to be in hands and not thrown); however, the tagger is not allowed to run with the ball.

- The pair needs to work together to get into position and pass the ball to get close enough to tag another player.

- Benefits of Game

- Communication and teamwork between the two taggers.

- Evasion (less constrained than Spider’s Web).

- Tactical abilities to target and home in on a player.

- Hand-eye coordination, throwing accuracy to moving target, catching ability.

- Scanning and awareness of surroundings.

- Change of direction and short accelerations.

- Anaerobic conditioning.

- Cone Scramble

- This works best with a minimum of six players.

- Randomly scatter cones down 1-3 meters apart (have one more cone laid down than the total number of people involved).

- Place two pylons down, one 10 meters away from the playing area, and the other one 15 meters away from the playing area (more on this shortly).

- Have the players circled up in the middle of the cones passing the ball quickly amongst themselves.

- When the coach shouts “GO!”, the player holding the balls runs around the 15-meter cone, and the rest of the players run around the 10-meter cone.

- The goal for the player with the ball is to step on two separate cones; the goal for the other players is to work as a team and prevent the player from stepping on two cones for as long as possible.

- The player with the ball cannot step on a cone if another player is touching it. As they run around looking for free cones, the other players must work to cover up the cones.

- Keeping a player from touching two cones for more than 30 seconds is incredibly challenging.

- Benefits of Game

- Communication between players to ensure cones are being covered (cannot cherry-pick a cone or else the player with the ball will win very quickly).

- Scanning and awareness of surroundings.

- Change of direction and short accelerations.

Since you’re here…

…we have a small favor to ask. More people are reading SimpliFaster than ever, and each week we bring you compelling content from coaches, sport scientists, and physiotherapists who are devoted to building better athletes. Please take a moment to share the articles on social media, engage the authors with questions and comments below, and link to articles when appropriate if you have a blog or participate on forums of related topics. — SF

References

Kinnerk, P., Harvey, S., MacDonncha, C., and Lyons, M. “A review of the game-based approaches to coaching literature in competitive team sport settings.” Quest. 2018;70(4):401-418.