[mashshare]

Midway through the first day of classroom work for my U.S. Soccer D License, there was a mutiny. The course instructors—a sage pair of A-Licensed coaches with decades of experience in U.S. Soccer—were whiteboarding the course curriculum and underlying methodology when, one by one, the two-dozen club coaches in the room began to revolt. We’re not talking about a minor quibble here or a semantic objection there—what ensued was a four-hour debate, calling into question the basic foundations of the program and threatening to derail the entire course.

The issue? Play-Practice-Play.

Known as PPP, the play-practice-play paradigm is a core element of U.S. Soccer’s “grassroots” initiative, largely inspired by the soccer development model in the Netherlands and U.S. Soccer’s Director of Sporting Programs, Nico Romeijn. Very simply, it’s a prescriptive model for organizing every practice session in the mode of that titular format:

- Play 1: Kids arrive at the pitch and immediately begin playing a scrimmage or largely uncoached series of small-sided games.

- Practice: Roughly one-quarter to one-third of the way into practice, the coach progresses into a game-inspired training session.

- Play 2: For the final third of practice, there is a full-sided scrimmage played to standard goals, ideally keying on the focal concepts from that practice portion.

And that’s it. Nothing more.

The question then raised (repeatedly, and in many cases, rather stridently), was the obvious one: If the players don’t actually have the technical skills, tactical understanding, or physical literacy to effectively perform in Play 1 or Play 2, when exactly are you supposed to teach those qualities?

Why PPP? A Digression

The D License (part of U.S. Soccer’s licensing pathway and traditionally geared for club or school coaches working with players above the age of 13) requires two full weekends of classroom and field work, separated by eight weeks of remote, mentored sessions and weekly homework projects.

During the two-month gap separating that spirited opening session and our final weekend of on-field evaluations, I took my youngest daughter out to practice pitching on what also happened to be the first day of fall practices for the local recreational soccer league. While she worked on locating her fastball and change-up, out on the grass in the distance a team of U14 girls launched their new season in two lines of eight players, with a girl from each line dribbling one at a time, down and back through five linear, evenly spaced cones. Each turn through the cones took 30 seconds or more, leaving over three minutes of inaction between low-intensity reps. The girls waiting in line were volleyball-bumping their soccer balls, chatting, or cloud-watching.

Closer to the softball infield, a team of U12 boys opened their season by taking several painfully slow laps around the full field complex, consuming anywhere from 12-18 minutes. With his gassed players sprawled out and sucking wind, the coach then spent the next 15 minutes lecturing his new team on a personal list of in-game pet peeves and everything they were absolutely not to do during the forthcoming season (defenders turning the ball towards the middle, attackers being called offside due to lazy positioning, being whistled for an illegal throw-in by lifting a back foot, and so on).

Rec soccer is the entry point into the sport for most players, yet 30 minutes into day one of a new season, one team still hadn’t touched the ball and the other was just killing time. Share on XIn a word, these practices sucked. Sucked to watch, and judging by the body language of the players, sucked to be captive to. Yes, these were recreational practices led by volunteer coaches, but recreational soccer remains the entry point into the sport for a majority of players. Here we were, 30 minutes into day one of a new season, and one team still hadn’t touched a ball while the other was already killing time.

The scenarios in those recreational practices are exactly what the PPP model is meant to prevent. What if, instead of bumping and setting their balls at the back of a line or lying half-dead and listening to a lecture, these players had showed up and immediately begun playing? Wouldn’t that make them more likely to:

- Make a continuing effort to arrive on time or perhaps even show up early?

- Be engaged from the moment practice begins, rather than needing to be herded and prompted?

- Have numerous live touches on the ball in a range of numerical alignments?

- Develop game-relevant fitness?

Most importantly, wouldn’t that be a sport they’d want to continue participating in? After all, it’s a game: You’re supposed to play it, and it’s meant to be fun.

Learning by Doing vs. Learning Then Doing

To support the philosophical foundations of PPP, in the D Course we watched a short video clip of a street soccer game being played in a dirt alley. Pickup style, with players spanning different ages and genders, all adapting to the constraints of the space while showing the creativity, decision-making, spacing, technical flair, and combination play characteristic of the beautiful game.

In addition to being more fun (and thus encouraging a higher percentage of youth players to stay in the sport), PPP is also designed to address a perceived shortcoming of high-level U.S. soccer players: They’ve been “overcoached” to the point of robotic predictability. So while the country produces instinctive and creative athletes on the basketball court and football gridiron—sports where it’s common for five or six kids to find a hoop or patch of grass and play their own version of the game—the U.S. has not managed to develop an Iniesta or Modrić or Pogba, those alchemic creators who capitalize on patterns and combinations in the game before others even recognize those elements exist.

U.S. Soccer designed play-practice-play to address the perceived shortcoming that high-level U.S. soccer players have been ‘overcoached,’ says @CoachsVision. Share on XIn the new grassroots initiative, U.S. Soccer hopes to inspire more pickup-style games and improve the country’s aggregate soccer IQ.

For those of us watching the video in the D Course, there was a natural follow-up question: How did the kids in that street soccer game learn to play a fluid, technical, and competent version of the game?

Yes, we can point to slick pickup basketball as a model for how players can test drive 1v1 moves, succeed and fail on their own terms, and flourish in a free-flowing and self-directed version of the sport. But what differentiates a fast-paced and electric pickup hoops game from a ball-hogging hack fest of chucked bricks and vigorously disputed traveling calls?

Answer: Well-coached players who bring their relevant skill sets to the pickup game.

I grew up playing pickup basketball on everything from school blacktops to community center gyms to a dank grid of courts below the freeway underpass, and my running mates were future high school, small college, and Division One players. A big reason we could seize and hold any court was that from third through eighth grade, our age group’s basketball team had a pair of outstanding coaches (one a former D-1 player himself) who taught us how to box out, set a pick, run a basic motion offense, fill the lanes on a fast break, make a proper bounce pass, and so on. Because we’d been taught how to play, we had the ability to jump into a pickup game and play with creativity and freedom. And because we knew how to play with creativity and freedom, we could then bring those elements back to our high school, small college, and D-1 teams.

Perhaps you see what I’m getting at.

What does a pickup version of soccer look like if you have a dozen kids whose parents did not grow up watching or playing the game, who have not yet learned basic technical and tactical skills, and who do not ever practice the sport on their own time?

Suffice it to say, we’re not talking about el jogo bonito.

The coaches rising up as part of the D Course mutiny had seen that scrimmage. It’s slow-motion kickball, with players setting off on a desultory hike for each successive ball booted way out of bounds. It’s a tiny fast kid dribbling up one sideline with a bumblebee clump from both teams trailing a pace behind. It’s toe kicks and bickering about handballs.

That game is the reason these coaches have jobs. They are paid to eliminate that version of the game via the design and purpose of their practices, not to use those practices to replicate it.

The Middle ‘P’ Is for Practice

As taught by U.S. Soccer, there are five basic elements for the “practice” portion of PPP, which should be present in every practice session:

- It must be organized (planned).

- It must be game-like (meaning there are opponents attacking and defending; the flow of play is directional; and there should be no interior cones, zones, or restrictions).

- There must be repetition (a chance to rehearse and improve).

- It must be challenging (a balance between success and failure).

- There must be proper direction (coaching).

Challenging point No. 2 was where our D-Course mutiny truly gathered force.

Stealing the ball is far easier than dribbling, passing, or trapping it. So how do you develop the latter fundamental skills if there is always an opponent kicking the ball away from the players’ feet? How do you teach spacing to young kids who don’t understand positional terminology without utilizing artificial landmarks like cones and zones? How do you develop passing techniques if there is always a goal and kids never stop cracking off shots? What if you happen to believe non-directional games like rondos and keep-away encourage possession, first touch, and 360-degree field awareness? If players start playing the moment they arrive, how do you conduct a functional warm-up?

Making it clear that they were channeling U.S. Soccer’s current perspective and not necessarily their own longtime coaching methods, the answers from our course instructors were:

- There will always be a defender in the game, so learning to dribble, pass, and trap with a defender present IS learning to dribble, pass, and trap.

- If kids only understand spacing by being restricted to the boundaries of a coned-off zone, they don’t truly understand spacing.

- Why wouldn’t you want your players cracking off shots every chance they get? Scoring goals is the object of the game.

- Sorry, that one’s a sticky wicket, but non-directional rondos and keep-away without goals do not meet the game-like criteria for a core practice activity in PPP.

- Players U10 and below can hit the ground running. If your players are older and you have an injury-prevention warm-up you believe in, do what you have to do when you have to do it.

Some of these answers make a great deal of sense when you think about them, some make sense in certain contexts, and some are completely unsatisfactory. Among our group in the licensing course, a Los Angeles-based coach took great pride in teaching individual ball skills to his teams of top flight teenage boys, and in that technical aspect, he dug in his heels to strenuously oppose PPP.

“What if I want to teach my boys how to do a step over? In this model, you’re telling me that I can’t do that in a practice session. You’re telling me we can’t slow down, remove the opposition, and teach the technical moves that will help them be more sophisticated and complete players. There’s no way this can work.”

Paradigms Come and Paradigms Go, But the Coach Is Still the Coach

It’s a good question, actually. How, in fact, do you teach a step over?

The answer is the usual one: It depends.

Personally, I learned the step over the same way I learned a crossover dribble in basketball: On my own. On the basketball court, playing the position I wanted to play required the ability to break down a defender, so I spent countless hours in my backyard practicing an arsenal of moves that I could use in a game.

So, if your players can already do a step over, easy enough, you don’t need to teach it. If they can’t do a step over, but also can’t dribble from Point A to Point B without falling headfirst over the ball, easy again, you have far more pressing needs and don’t need to teach it. If you have the time and ability to teach 1v1 moves in practice and your players are able to use that coaching to effectively execute those moves on the field, awesome, do your thing.

Coaching sports—like playing them—is about problem-solving. Just as we don’t want robotic and predictable players, we don’t want robotic coaches; there is no single solution that will be effective across the board and there is no model that will apply to every situation.

Coaching sports—like playing them—is about problem-solving. Just as we don’t want robotic and predictable players, we don’t want robotic coaches, says @CoachsVision. Share on XAs an absolutist structure to follow for a calendar years’ worth of practices, PPP is, to say the least, highly debatable. As a lens to scrutinize your own practice design, PPP can be very useful to help sharpen your purpose and approach:

- In this session, are your players learning to play at speed, or are these skills they can only replicate in static situations?

- Are there elements of attacking, defending, and transition that apply directly to the dynamic elements of the game?

- Are they learning to make their own decisions in the context of the game, or do your players need to be “joysticked” by a coach to make effective plays?

- Is this 90-minute session any fun? Would they want to come back and do the exact same practice again?

If you coach a rambunctious gaggle of 8-year-olds, PPP might very well be an effective method to harness that energy and structure the bulk of your practices. If you coach a group of steely-eyed 14-year-olds who show up each day expecting you to push them one step closer to a spot on the next high-level team… perhaps PPP is a changeup you toss in every so often for variety’s sake. The model is something that you can use all of the time, some of the time, or not at all (but if not at all, you ought to have sound reasoning for why not at all).

Several years ago, when I took the E License course, U.S. Soccer taught a completely different, progressive plan for structuring training sessions:

- Warm-up

- Small-sided activity

- Expanded small-sided activity

- Game

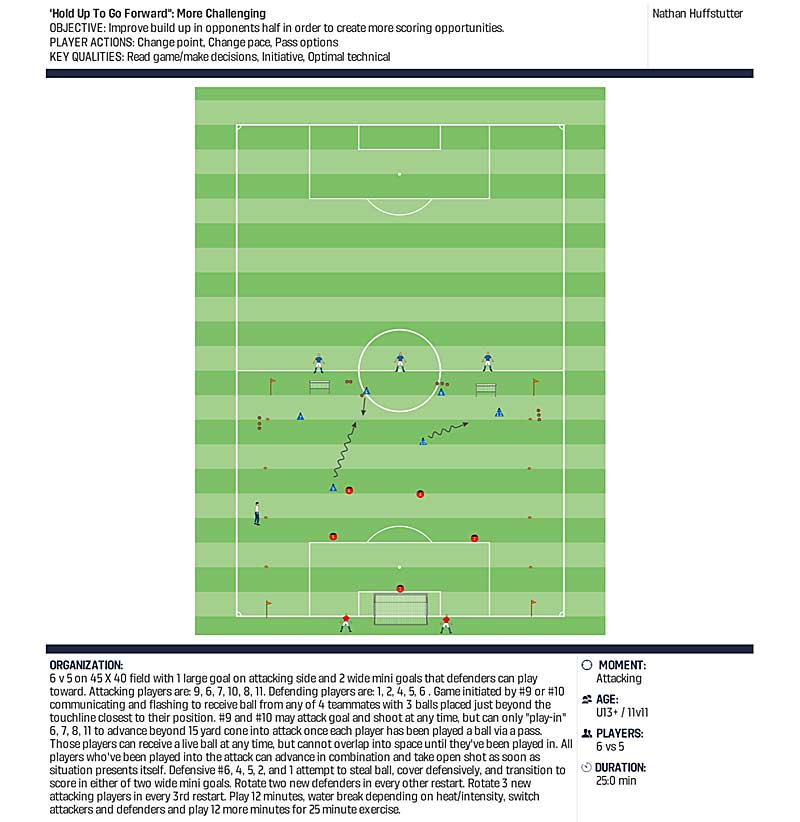

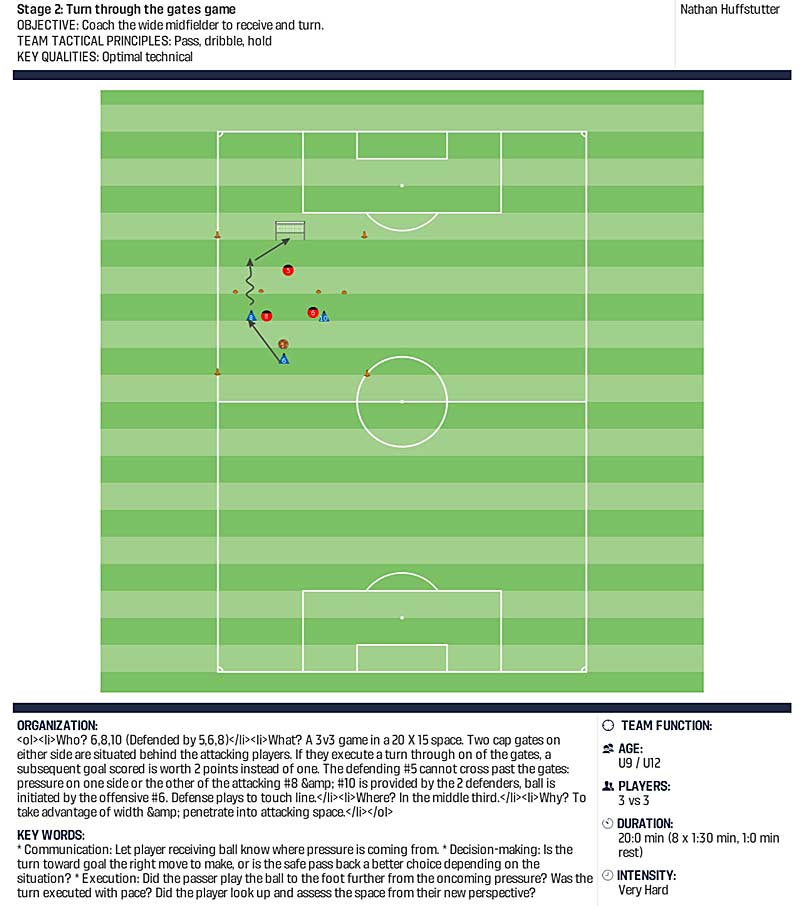

In those small-sided activities, the coach targeted a skill or game moment and tried to impose conditions to emphasize it. The topic given to me for the final project of my E License evaluation was “coaching the wide midfielders to receive and turn.”

Quite a specific topic, as were the rest. For our field evaluations in the E Course, each coach invented a technique-specific game that highlighted their topic with a baroque set of rules, constraints, and scoring systems that were, theoretically, meant to inspire repeated execution of that focus skill.

Perhaps at some point you’ve tried inventing such a game for your own players—perhaps it even worked. In my experience, however, each time I create a unique game with its own set of rules, scoring systems, and constraints, I then have to spend 15 minutes that I will never get back explaining those rules, scoring systems, and constraints, all while my once-warmed-up players gradually become de-energized and confused.

Typically, those players then pepper me with very logical questions about hypotheticals, contingencies, and gray areas in the rules I hadn’t anticipated. Then, they play this inventive new game at ~60% speed because it’s very hard to sprint all-out while simultaneously figuring out new rules. Ultimately, the big takeaway becomes the efficient ways they learn to cheat the game and rack up easy points, rather than getting any better at the focus skill.

Two major lessons from that practice model:

- The only way to effectively play a game is to understand the rules. If you stick to rules the players already (mostly) know—meaning the standard laws of the game—your players will spend more time playing at speed and you will spend less time in formal arbitration over esoteric rules or exhorting your players to please, please, please compete with game intensity.

- While manipulating games to emphasize a focus topic may not work too well, having a focus topic for every practice session gives shape to those sessions and provides building blocks from week to week.

Though U.S. Soccer no longer promotes that system, I like the flow of it and often plan practices with that four-part structure. Tellingly, though, while I have never once considered replicating my final E Course session for one of my own practices, I have used variations of my PPP design with players ranging from U10 Recreational All Stars to U14 competitive players, with equally positive results.

Improving the State of Youth Soccer

Let’s get real. Players get better in practice, but they aren’t made there. Athletes who already have the physical skills and mental attributes to excel at the game also tend to succeed on the training pitch—but it is not an A/B test where those players would be X-amount better if one practice model had been applied versus another.

Those who lament the state of youth soccer in the U.S. have ample avenues for complaint: Club soccer is cost-prohibitive; the pressure for early specialization discourages talented multi-sport athletes; there are major issues with burnout, overuse injuries, and competitive stress; and so on.

In my lifetime, however, I’ve seen an exponential improvement in youth soccer. Growing up in a mid-sized city in the 1980s (Eugene, Oregon) and playing on the most advanced teams in the area from first grade through high school, my teammates and I could name exactly three soccer players: Pele, Juli Veee, and the guy Stallone played in Victory. I had my driver’s license before I had a soccer coach who’d ever set foot on a soccer pitch as a player, being coached instead by a succession of volunteer dads who’d never so much as seen a soccer match on television, then a middle school wrestling coach, then a freshman cross country coach, and finally a high school coach who’d played the sport but didn’t care one bit for teaching it to teenagers.

As the game has exploded in the U.S. over the past three decades, the question is not so much how to improve the state of youth soccer, but how to do so in a more sustainable way. U.S. Soccer’s grassroots framework and PPP model are positive steps in that direction, recognizing that there is an entire generation of players who have grown up practicing two, three, or even four times a week in order to play a weekly game that’s shorter than any one of those practices. Correspondingly, there is a generation of soccer parents who believe that training for the sport should resemble SAT test prep—they associate drills with a concrete ROI and scrimmaging as a cousin to recess. When they pay club fees and fill out coaching evaluations, they envision a coach running a soccer boot camp, not one standing out of the way while the players just… play.

As the game has exploded in the U.S. over the past three decades, the question isn’t how much to improve the state of youth soccer, but how to do so in a more sustainable way, says @CoachsVision. Share on XConsequently, as an extracurricular activity, youth soccer is often described with phrases like: it’s a grind, it’s a long haul, it’s stressful, it’s exhausting, it’s tedious. These descriptions, however, are a response to the practice demands of the sport, not the game itself. Coaching, again, is problem solving. If your players love to come to practice—Bingo! You’re probably doing something right. If they begin associating the sport with a boring, obligatory, time-consuming grind, it’s worth considering ways for them to play more with methods like PPP. After all, it’s a game, you’re supposed to play it, and it’s meant to be fun.

Since you’re here…

…we have a small favor to ask. More people are reading SimpliFaster than ever, and each week we bring you compelling content from coaches, sport scientists, and physiotherapists who are devoted to building better athletes. Please take a moment to share the articles on social media, engage the authors with questions and comments below, and link to articles when appropriate if you have a blog or participate on forums of related topics. — SF

[mashshare]