Three sports, preparing lesson plans for two different subjects, other duties as assigned, and attempting to balance a life outside of work. Sound familiar? This was my life as a high school sport coach. Did I realize that nutrition was important for athletes? Of course—but I never quite seemed to find the time to address the topic thoroughly. Instead, I relegated nutrition talks to pearls of wisdom like “no fried food on game day” and kept a clear spot on my desk for a coach of the year award. After all, when knowledge bombs of that magnitude detonate, people notice.

Fast-forward several years. I’m the full-time strength and conditioning coach at Byron Nelson High School in Trophy Club, Texas. This allows time to put together curriculum like a Sports Nutrition 101 presentation. In a perfect world, this lesson would occur on day one of an athlete’s high school career. However, few aspects of training the high school athlete are optimal. So, when does this nutrition talk happen?

It happens when it happens.

Sometimes a class period is allocated during the pre-season or early off-season. Sometimes the longer presentation is broken up into 5-minute segments delivered at the beginning of team character lessons. Sometimes, there is no presentation. Instead, there might be a brief discussion held at the end of a team lift. Often, the best nutrition talks are ones that are off-the-cuff but relevant to the current circumstance. The temperature is 105 degrees this week? Perfect! Let’s talk hydration because the environment makes those little ears receptive.

To keep things as simple as possible, we discuss four basic principles:

- Eat early

- Eat well

- Eat often

- Build a performance-enhancing plate

If an athlete hears nothing else and abides by these guidelines, they’ll be off to a great start.

Eat Early

Breakfast is the most important meal of the day. End of topic, next slide! But is it? Ask a room full of athletes what they ate for breakfast, and you’ll hear something along the following lines:

Athlete 1: “Pop-Tarts and a Gatorade!”

Athlete 2: “Fast food!”

Athlete 3: *Blink* “Ummm” *Blink* (Translation: I didn’t eat and rarely do.)

In cases one and two, we have a black-and-white teachable moment: make better choices. But case three? Many athletes report not having an appetite in the morning or avoid eating before morning workouts because they fear they’ll get sick. Both are valid concerns. But we can train the digestive system to tolerate food just as we train the body to run faster and lift more.

We can train the digestive system to tolerate food before morning training just as we train the body to run faster & lift more, says @missEmitche11. Share on XAlthough this may sound silly, a non-breakfast-eater may need to start small. The first day’s breakfast might be a single cracker. Day two: add another cracker. Day three: add peanut butter. Eventually, they should tolerate a more substantial amount of food before training.

In most cases, athletes should pair carbohydrates with protein at all meals and snacks.

For morning training sessions, however, a bland, high-carbohydrate snack can give athletes the fuel they need without causing digestive distress. Dry cereal, toast, granola bars, or a PBJ are all great options.

Eat Well

Eat well is another seemingly obvious statement, but one that can prove overwhelming. Read five articles and you’ll get five different answers as to what constitutes a healthy diet. Further complicating matters, high school athletes are often at the mercy of their parents or their school to provide meals. Again, the environment is rarely optimal, but the goal is to make better choices within that environment.

H.S. athletes are at the mercy of their parents or school to provide meals, so we teach how to make better choices with what's available. Share on XThe first order of business is to alleviate the concern that one can never eat Reese’s or Pop-Tarts again. Often, people hear the word nutrition and shut down because they see it as too restrictive. Instead of aiming for 100% compliance, most people are very successful following an 80/20 plan. This means eating for performance 80% of the time and eating for pleasure 20% of the time. It’s a great jumping-off point to discuss what fueling for performance actually means.

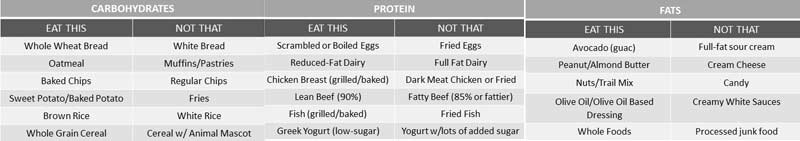

First up on the agenda is discussing the role and best choices for each of the macronutrients: carbohydrates, proteins, and fats.

Carbohydrates

Carbohydrates are the body’s primary source of energy. While the Keto diet may be all the rage, carbs should make up the bulk of the diet for athletes participating in high-intensity sports. Based on their chemical structure, carbs are classified as complex or simple.

While Keto may be all the rage, carbs should make up the bulk of the diet for athletes participating in high-intensity sports, says @missEmitche11. Share on XSources of complex carbohydrates are whole grains, sweet potatoes, rice, pasta, and bread. Simple carbohydrates are found naturally in foods such as fruit and are added commercially in the form of sugar. Athletes should primarily focus on consuming complex carbohydrates because these provide more sustained energy. Simple carbs are used as a quick burst of energy 30 minutes before training or as fuel during practices or games lasting longer than two hours.

Proteins

Ask a room full of athletes about the role of protein in their diets, and you’ll likely receive the emphatic reply, “protein builds muscles!” The importance of protein is widely known, yet few athletes consistently consume enough of it. One issue is that athletes are often unaware of the best sources of protein. Lean proteins like white-meat chicken, fish, low-fat dairy, whey protein powder, eggs, and egg whites are all great choices.

Athletes also may not be clear on when they should consume protein. They should eat protein with carbohydrates at each meal and snack, except immediately before exercise. Not only does this increase total protein consumption, but it also promotes stable blood sugar.

While most athletes have never considered blood sugar outside of the context of diabetes, it tends to be one of the easier concepts for them to understand. Low energy, the shakes, lack of focus during 3:00 pm classes, and being hangry are all states athletes can remedy by stabilizing blood sugar. Hangry gets a laugh out of the group and gets the point across that protein is more than just filling out a size smedium jersey. It has a direct effect on energy levels, focus, mood, and performance.

Fats

While a performance-enhancing diet is low in fat by design, athletes must include healthy fats in their diet. Not only are fats important for cell membrane structure and hormone production, but certain types of fats (omega-3 fatty acids) also serve as powerful anti-inflammatories.

Since a gram of fat contains nine calories (versus four calories per gram of carbohydrate or protein), adding healthy fats can increase caloric density without increasing food volume. Caloric density is critical for an athlete attempting to gain weight. Nut butters, olive oil, avocado, and fatty fish like salmon are all sources of healthy fats.

With each of these three macronutrients, I share an eat this, not that chart and discuss relative digestion time. From fastest to slowest: Simple carbs < complex carbs < protein < fat.

I include digestion time for two reasons. First, it explains that a high-fat meal like fast food slows digestion and diverts blood flow away from the working muscles. This leaves an athlete feeling sluggish and impairs performance. Second, digestion times tie into our third principle: eat often to have energy available for training.

Eat Often

Ultimately, we want an athlete’s diet to maximize the amount of energy available during workouts and for recovery between sessions. This means eating a sufficient amount of quality calories, keeping energy (blood sugar) levels stable throughout the day, and staying hydrated. Though eating 5-7 meals and snacks throughout the day is a great guideline, it’s helpful for athletes to understand what this looks like within the scope of their day.

Meal timing around training is summarized as follows:

- A full meal 3-4 hours before a training session

- A high-carbohydrate snack ~30 minutes before training (skip protein pairing here—the goal is quick energy and ease of digestion)

- Ingesting simple carbohydrates when a training session is longer than 2 hours

- Consuming recovery nutrition 0-2 hours post-training session

Wonderful, all set! Except this isn’t how school works. At. All. Based on class schedules, some kids have lunch at 10:30 am. After-school practice is five hours later. For these athletes, the neat little schedule of meal-snack-meal-snack, etc., doesn’t work.

Instead, their eating schedule could be meal-meal-snack-snack-snack-meal. Some might opt to snack at 10:30 am and take their meal to class so they can eat around noon, 3-4 hours before practice. Again, the high school setting is never optimal. Good news! Life rarely is—we have to adapt and prepare accordingly.

After we’ve laid out the schedule, we discuss the three goals of recovery nutrition:

- Repair—take in protein to repair muscle damage accumulated during the training session

- Replenish—consume carbohydrates to replace glycogen used for energy during training

- Rehydrate—drink fluids to match loss during a training session

Within 45 minutes of exercise, athletes should drink fluids and eat a snack with a carb:protein ratio of between 3:1 to 4:1 grams. An easy and relatively cheap solution during this 45-minute window is 12-20 ounces of low-fat chocolate milk. Within 2 hours of a workout, athletes should consume a full meal following the plate method, our fourth and final concept.

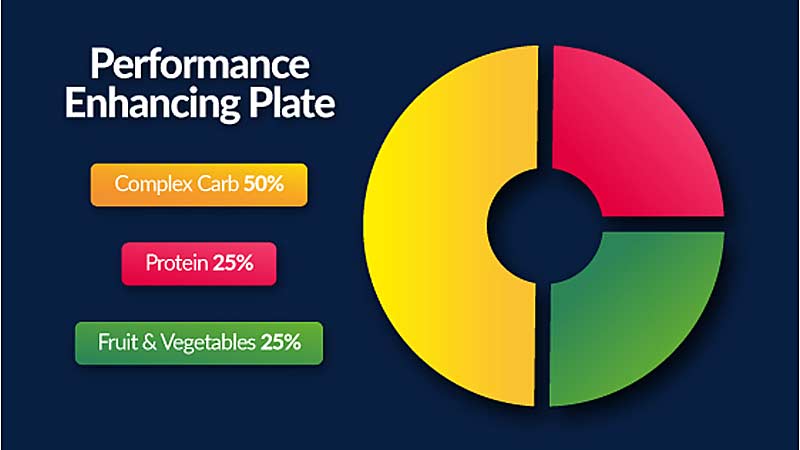

The Plate Method: Putting It All Together

With most nutritional bases covered, it’s time to discuss how this looks within the context of a meal. In general, an athlete’s plate should be ½ complex carbohydrates, ¼ lean protein, and ¼ fruits and vegetables. A small salad and healthy fats are great additions to the well-balanced plate.

A solid template, but still requires a little creativity. Of course, chicken, brown rice, and broccoli make an excellent meal, but realistically, how many student meals look this way? How often does that plate pass through a school cafeteria? Spoiler alert: never.

Our group activity comes in handy here. I place athletes into groups of 2-3 and direct each group to write down a meal that would benefit an athlete. For efficiency’s sake, I assign each group either breakfast, lunch, or dinner and provide a sheet of paper with a blank plate printed on it to guide their selections. But we don’t start quite yet.

Since kids can be incredibly literal, generalizing the plate method to traditional meals can be a disaster without a little nudge. Instead of turning them loose and having five groups present a strange amalgam of sardines, broccoli, and pasta (true story), I lead the activity by presenting a few options they might overlook to get to the “right” answer:

Sample Meal 1: Breakfast Burrito

- Corn tortillas (complex carb)

- Eggs, turkey sausage, a sprinkle of cheese (protein)

- Fruit (fruit)

Sample Meal 2: Sandwich Box

- Whole wheat bread, side of baked chips (complex carb)

- Turkey, cheese (protein)

- Lettuce, Tomato, side of fruit (veg/fruit)

Sample Meal 3: Spaghetti

- Pasta (complex carb)

- Lean ground beef (protein)

- Red sauce, side salad (veg)

Armed with a few ideas, groups have about two minutes to build their plates. After the time expires, the small groups present their culinary masterpieces to the team. Tragically, Pop-Tarts have yet to make the cut. And now they know that—though a legitimate source of protein—any mention of sardines will result in the loss of speaking privileges due to the retching noises it elicits from the crowd.

Wrapping It Up

As with many areas of athletic performance, when it comes to nutrition, full-time consistency beats part-time intensity. The more times an athlete is exposed to information, the more likely they are to act upon it.

When teaching nutrition to athletes, full-time consistency beats part-time intensity, says @missEmitche11. Share on XIn addition to formal presentations and post-workout huddles, coaches can model these behaviors in their own diets, ensure that team meals include the four principles, and educate parents. It takes time and effort, but as the saying goes: the person at the top of the mountain didn’t fall there.

Since you’re here…

…we have a small favor to ask. More people are reading SimpliFaster than ever, and each week we bring you compelling content from coaches, sport scientists, and physiotherapists who are devoted to building better athletes. Please take a moment to share the articles on social media, engage the authors with questions and comments below, and link to articles when appropriate if you have a blog or participate on forums of related topics. — SF

Very educative article.

Great information in a short easy to read and understand format that left us feeling like we can do this!

Great article, I’m a teacher, coach and parent, Teaching nutrition to my players and daughters is important as I see them making decisions to keep them “skinny” which is not the way to go about it. I would love to learn more about your lessons. Please email me on some details.

Thank you

I very much appreciate this article. I am a high school/Provincial Lacrosse Coach in Canada and understand the importance of proper nutrition for student athletes. this makes it easy to relay the information so that my students understand and can effectively maintain healthy habits.

I love this article! Simple, true and I believe it will be effective. I’m going to teach it to our freshman/sophomore class of football players! Excited to see the results!

I like what I read!

Email info please, on I can help my high school athletes !

Do you have a curriculum/plan ready to be followed by HS Coaches?

Excellent information. I have been an athlete my entire life …. But I participate in sports in a generation where nutrition didn’t even get a thought. So now researching for my son. This is great lead in info for athletes, their parents & coaches.