I started my career training the general population in a commercial gym. Client retention was fairly straightforward. (I won’t say easy, but straightforward.)

I had the opportunity to develop a relationship with the key stakeholder, the client, with each and every session I delivered. They were there, I was there, we trained, laughed, became friends, chummed around, and life was good. If there was ever an issue—be it financial, with their perception of my service or training programs, or otherwise—I could talk with the client directly and hash it out.

Business was fairly simple. Again, I won’t say easy, but simple. Meet the client, sell the client, train the client, retain the client.

Then I transitioned into training youth athletes.

I realized an interesting conundrum a few months in. These kids weren’t paying for training themselves (most of them)—their parents were. But unless the parent was particularly involved and either came to the sessions or took the time to call or email, I often wouldn’t see or hear from them for weeks.

It was particularly awkward when I reached out to those who opted out of automatic payments about their monthly bill.

“Hey, I know we haven’t talked in a few weeks and we’ve only met once, but can you pay me now? Great, we’ll chat again about this again next month…”

Of course, it didn’t go down exactly like that, but that’s kind of how it felt.

Further, I can only imagine what the kids themselves said when asked about training.

“Hey little Johnny, how was training today?”

“Good.”

“Oh, good. What did you do?”

“We ran and stuff.”

“You ran and stuff…ok, cool…do you like it?”

“Yea, it’s cool.”

“Oh, it’s cool…well, alright then…what should we do for lunch?”

That doesn’t exactly leave a great impression. And it’s not the kid’s job to inform their parents about training anyway—it’s mine (and yours). It wouldn’t be long before I wouldn’t want to pay for my own children’s training if that’s all I knew about it.

A relationship with the parent is a safeguard against losing clients. It’s a lifeline of the youth development business, says @KD_KyleDavey. Share on XThis dynamic forced me to think outside the box and figure out how to build a genuine relationship with parents I knew I would rarely see. I believe it’s much easier for parents who don’t know me to remove their children from training. Thus, a relationship with the parent is a safeguard against losing clients. It’s a lifeline of the youth development business.

I’m pleased to say I think I do a pretty good job of connecting with parents now. Below are three strategies I’ve instituted to help myself out.

Always Do the Initial Consultation with the Athlete AND the Parent

You should want to get to know the parents just as much as you want to get to know the athlete. Remember, the parents are the ones paying the bill.

It isn’t necessarily wrong to do a consult without the parent present, but it is a huge missed opportunity. Having dedicated time set aside for nothing more than talking is rare. Without the consultation, you’re left with small talk before and after training sessions, phone calls, and emails to build a relationship. Capitalizing on the consultation is key for starting the relationship off on the right foot and setting the stage for it to remain strong down the road.

How exactly do you make the most of the consult? Turn on the charm you learned from How to Win Friends and Influence People?

Sure, put your social skills to work. Find common ground, build rapport, blah blah blah. Beyond that basic sales stuff, there are two sections of the consult that present significant potential in building a relationship with the parent.

History Taking

Most of you will do some sort of history taking with the athlete, asking questions like “Have you ever had any injuries?” and “What type of training have you done before?” After asking these standard questions, turn to the parent and try these three:

- What sports did you play?

- What have you noticed about [insert their child’s name]’s performance in the past?

- What do you think it is that he/she enjoys about sports?

These three questions are targeted. In my opinion, it’s important you ask them in order.

Assuming the parent did indeed play a sport, the first question builds credibility and subtly sets them up as an authority on the child’s sports performance. Everyone likes feeling like an authority, perhaps even more so when it comes to their own kids.

Everyone likes feeling like an authority, perhaps even more so when it comes to their own kids, says @KD_KyleDavey. Share on XThe second question lends itself to that newfound authority, putting the parent in a position to offer critiques and recommendations about how the child can improve. The kid might not like this part very much, but the parent will. Besides, it’s not like kids aren’t used to parents pointing out where they can improve.

The final question tugs on the heartstrings and lets the parent expound on how well they know their own child. It’s an emotional question, and relationships are emotional. You’re opening the emotional door and encouraging the parent to walk through it with this one.

Regardless of the answers you get, the fact that you asked the questions in the first place shows you’re just as interested in the parent’s thoughts and feelings as you are in the athlete’s. This is a small investment in time and effort that yields a big return: The parent knows you care and likes you more for it.

Goal Taking

What is every athlete’s goal? To be the stud. Athletes say they want to run faster, be stronger, hit harder, or whatever else they think will help them become the star. You know as well as I do that you get the same superficial answers every time you ask an athlete what their goals are.

Beneath these, however, is always a deeper motivation. The infamous “why.” Asking an athlete why they want to accomplish whatever goals they’ve stated will always lead to a deeper truth. Getting an honest answer is an art that deserves an article (or a book) to itself. For now, I’ll simply say always ask why, ask in different ways, keep asking until you get an emotional answer, and ask in front of the parent.

You’d be surprised how many parents haven’t asked their own child this question or know their child’s answer. That you ask catches their attention, and if the child feels comfortable enough to tell you the truth, the parent will have learned something deep and important about who their kid is, thanks to you.

What impression do you think this leaves? Let’s just say it’s good.

Equally as important as asking the athlete’s goals is to ask the parent what their goals are for their child, both in athletics and overall in life. Try asking these two questions:

- What are your priorities for your child?

- What are your goals for your child’s athletic career?

Just as the parent may be surprised by the child’s answers, the child may be surprised by the parent’s answers, and they may grow closer to each other as a result. Speaking as a parent who already feels close to his children, there’s nothing I wouldn’t do to grow even closer, and I would certainly feel indebted to and appreciative of anybody who helps me do so.

Further, from a practical perspective, understanding what the parent values puts you in a better position to recommend a training program and earn the sale by speaking to the parent’s interests. If injury prevention—i.e., their child’s safety—is the parent’s number one goal, as is often the case, focus your rhetoric there before asking for the sale, for example.

Create a Viewing Space

This seems like a no-brainer as I type it. Make sure there is a space in your facility where parents can sit comfortably and watch their children train. It doesn’t need to be a five-star lounge, but it should have seating and a clear view of the training space. Bonus points if it’s close enough to the training area for the parent to hear you coach. It’s like having a sideline ticket to every training session.

There are several advantages to this. I’m convinced that parents who show up to training sessions are less likely to withdraw their children from training. If a parent has been to the facility and seen their child work hard, succeed, and (hopefully) laugh and have fun, the benefits of your program are more numerous, apparent, and top of mind than they are to absentee parents.

Make sure there’s a space in your facility where parents can sit comfortably and watch their children train. Bonus points if it’s close enough to the training area to hear you coach. Share on XI can anticipate some of you saying, “Well the parents who show up to sessions are the committed ones, and they aren’t pulling their kid out of training anyway.” Yes, that may be true. But it isn’t an excuse for your facility’s physical setup to be aversive for less zealous parents. For many adults, an inviting space is the difference between staying for the session and leaving. Don’t miss these opportunities.

Set up a countertop or table space for them to work, make sure they have access to the Wi-Fi, and openly invite them to attend training sessions. With so many parents working from home these days, you’d be surprised how many will come and set up shop in your facility to get an hour or more of work done while their kids do the same.

While they’re there, you’ve got a golden opportunity to talk to them and build a relationship. I often do this while the kids complete the warm-up. It’s easy enough to keep an eye on the group while lending an ear to the parent, and it grants the athletes a little bit of what every young person craves: autonomy.

Here’s another great benefit of having parents stick around: If you’re really good at what you do, you’ll attract parents who know a thing or two about performance training. I’ve been surprised more than once by how knowledgeable a few of my athlete’s parents are. A few high-level football coaches have brought their kids in to work with me. A couple weeks into training, and as they began asking more questions about what we’re doing and why, I realized these guys really knew what they were talking about, and they’d been evaluating my training program and skill set from the start.

That they could see and hear everything I did with their kids bought me a ton of credibility, because they found out I knew what I was doing, too. But without that viewing space to watch and listen what went on during training, I’d be a question mark in their mind instead of an exclamation mark.

As a result, I earned from them the ultimate sign of trust: client referrals. When the head coach of a collegiate football program refers the local high school kids that he’s recruiting to your training program—well, need I say more about how good of a thing that is for business?

Last point on this topic: Get a TV that supports Apple’s AirPlay function and put it near the viewing space, especially if you evaluate sprint kinematics.

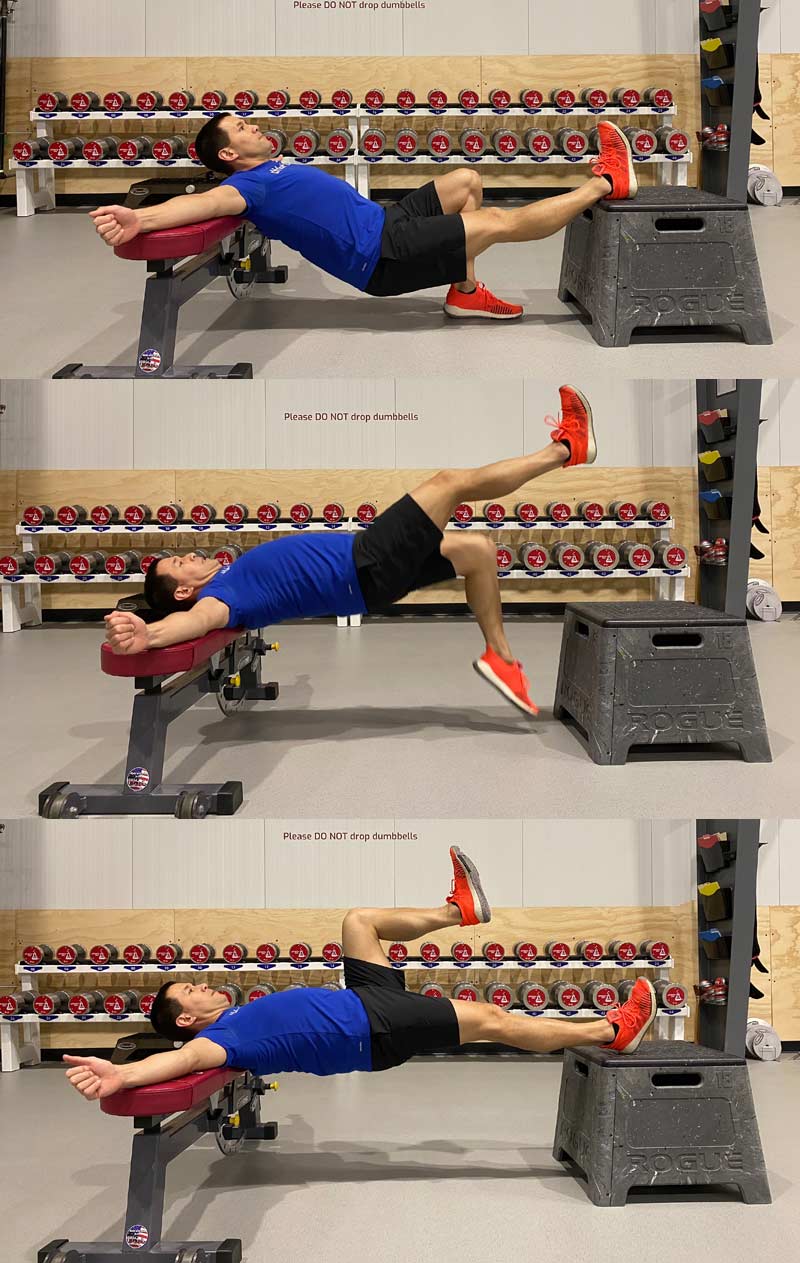

Readers of this site likely are familiar with the concept of teaching kids how to run, but the general public still isn’t. When you review film with the athletes, make sure the parents can see the screen too. First of all, it’s just cool. Many adults are curious about the X’s and O’s of how to sprint faster, so they’ll enjoy hearing you talk and watching their own kid in slo-mo.

Second, when you point out that heel striking sends more shock (layman’s terms) through the ankle, knee, and hip joints than a ball of foot strike does, and thus increases the chances of developing aches and pains, or when you talk about why anterior pelvic tilting increases the likelihood of pulling a hammy, you’ll catch the parent’s attention, because they don’t want their kid to get hurt.

If you can keep their baby safe—which, you can, as strength training and sprint technique work do decrease injury incidence—they’ll love you all the more for it. Again, spoken as a parent, there’s nothing I wouldn’t give to protect my babies from injury.

A picture is worth a thousand words. Showing a before and after photo of sprint technique can be a huge selling point, especially if it’s on day one of training, says @KD_KyleDavey. Share on XAnd to wrap this section up: A picture is worth a thousand words. Showing a before and after photo of sprint technique can be a huge selling point, especially if it’s on day one of training. In my experience, cleaning up starting technique is fairly easy to do, is an important sprint KPI, and can create one hell of a before and after picture for parents and athletes alike to see.

Start a Parent Newsletter

I admit, even if you set up a killer viewing space, you’ll still train kids whose parents you never see. Maybe the kids drive themselves, carpool with buddies, or are dropped off and picked up without their folks coming inside.

How can you bridge this gap?

I answered this question by starting a parent newsletter. Every parent gets an email from me once per week called “This Week in Training” in which I share highlights of the week, give shout-outs to athletes who have set a PR or earned athletic or scholastic honors, share a tip about injury prevention, or whatever else I see fit.

This way, if I never see the parent after the consult, at the very least they hear from me once per week with good news about how awesome our athletes (including their child) are doing.

These emails demonstrate the value of training in a subtle way. The newsletter communicates “Hey, I still exist (I know you have a busy life—you didn’t forget about me, did you?). I do good work, and it shows because our athletes are doing awesome. Thanks for letting your kid train here, they are becoming more awesome with every session!”

Of course, I don’t write that, but that’s the message that gets delivered.

And while I don’t think of this newsletter as marketing so much as I think of it as simple communication, it does indeed turn into marketing, because I never remove parents from the list, even when their children stop training. They have the opportunity to unsubscribe, but I don’t do it for them.

This works out great, because whether the athlete cancelled training because their season started, for financial reasons, or whatever, the parent gets the same message in their inbox every week: “Hey, I still exist (you didn’t forget about me just because your kid stopped training, did you?), and I’m still doing great work! If your kid comes back to training, they will get a lot better, just like these kids are!”

There’s been a few times when parents of ex-clients have replied to the newsletter asking to sign their child back up. The weekly newsletter made it easy for them to do that—much easier than remembering and finding time to call or email me on their own, and much easier for me than going through my list and calling my previous clients seeking their business. In fact, in these cases I didn’t ask for their business at all, I simply wrote my weekly newsletter.

For the more scientifically minded than business-minded coach: The email provided an affordance.

To set up a newsletter for yourself, you’ll want to use a service. Don’t just copy-paste email addresses into the “to:” bar each week. It’s tacky, and I think it might be illegal (but don’t quote me on that: I’m a trainer, not a lawyer).

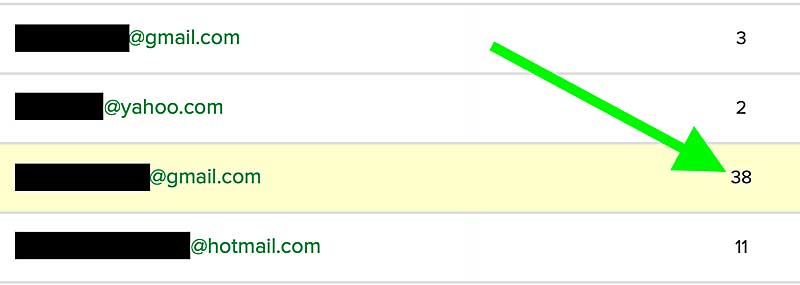

I use the free version of MailerLite. It’s simple, allows you to build an email template to use weekly, and (my favorite part) it gives you metrics for every email you send. These include the absolute number of opens, who opened it and how many times, the amount of times links were clicked, and who clicked them.

I can tell you from experience: When you highlight an athlete individually in the newsletter, their parent reads it, re-reads it, then re-reads it again. I’d say that’s a pretty good way to make a parent proud, provide positive associations with your business, and secure future business.

In case you did like many readers do and skimmed this article instead of reading it closely, here’s the central theme: The parents are the bill payers, and you must make targeted efforts to build quality relationships with them in order to secure their business for the long run. Aside from delivering results to their children, making it easy for parents to trust and like you is critical to your success as a youth development trainer.

Interviewing the parent along with the child during the initial consult, allowing the parent to sit and watch training in a comfortable space close to the training floor, and communicating once per week via a newsletter are three easy steps you can take to ensure a positive relationship with the parents of your athletes, and a brighter future for your business.

Since you’re here…

…we have a small favor to ask. More people are reading SimpliFaster than ever, and each week we bring you compelling content from coaches, sport scientists, and physiotherapists who are devoted to building better athletes. Please take a moment to share the articles on social media, engage the authors with questions and comments below, and link to articles when appropriate if you have a blog or participate on forums of related topics. — SF

Mike Young, PhD, is the Director of Performance for Athletic Lab, the North Carolina Courage, and North Carolina FC. He’s also the head coach of Athletic Lab Track Club. In individual sports, Mike has coached athletes to international teams in four sports (weightlifting, skeleton, bobsleigh, and track and field). In team sport settings, Mike has worked in the MLS, USL, and NWSL and most notably has assisted the winningest women’s soccer team in American history and more than a dozen World Cup players.

Mike Young, PhD, is the Director of Performance for Athletic Lab, the North Carolina Courage, and North Carolina FC. He’s also the head coach of Athletic Lab Track Club. In individual sports, Mike has coached athletes to international teams in four sports (weightlifting, skeleton, bobsleigh, and track and field). In team sport settings, Mike has worked in the MLS, USL, and NWSL and most notably has assisted the winningest women’s soccer team in American history and more than a dozen World Cup players.