Clubhead speed and its close relation, ball speed, are the objective standards for singular outputs in golf. These, combined with availability, are the aims of any strength and conditioning intervention in golf. Of all the objective measures we use at the European Tour Performance Institute, club head speed (CHS) is part of our quartet of isometric mid-thigh pull, countermovement jump impulse, and ball speed.

For the uninitiated, club head speed is how fast you move the head of the golf club just before impact. Roughly, for every extra 1 mph faster you swing the club, you can increase your driver distance by 3 yards. On the PGA Tour, the highest recorded club head speed is current 138 mph (Bryson Dechambeau, 2021 season) and the best 10 years ago was 127 mph (Bubba Watson, 2010 season—note Bubba’s 2021 best is 123 mph). While this is an 11-mph improvement, the tour average has only improved around 1 mph, from 112 to 113 mph. The PGA Tour itself has stated, “It can be seen that average club head speed has increased by 1.7 mph from 2007 to 2019 and ball speed by 4.9 mph.”

This isn’t representative of what the players who occupy the top 15 of the PGA Tour are doing, as all have average club head speeds higher than 120 mph. Sure, comparing players is not a one-to-one endeavor as it relates to golf performance—no one is winning club head speed tournaments—but it illustrates that motivated players can exploit output variables to give themselves more options.

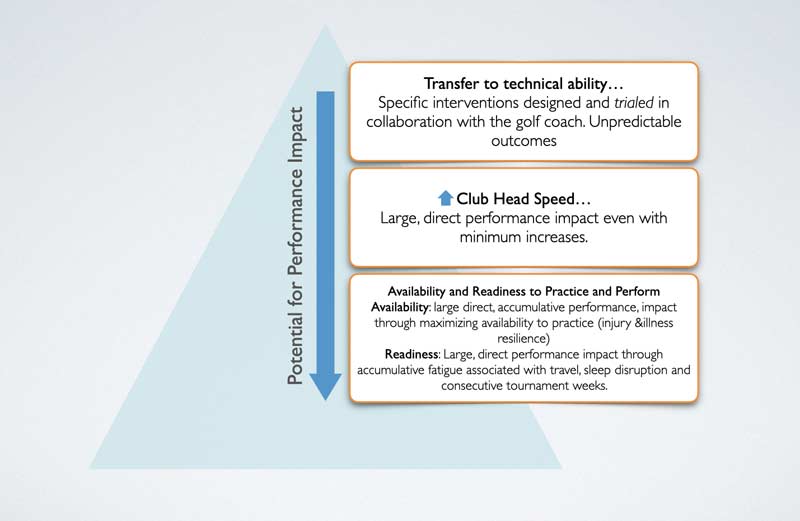

Club head speed is the real-world impact measure that correlates with our other physical measures (for golf athletes), says @WSWayland. Share on XClub head speed is the real-world impact measure that correlates with our other physical measures as shown by research performed by Wells et al. (2020) on our Challenge Tour players. Players with high club head speed are generally stronger and more explosive and have more body mass. However, club head speed alone is still a single measure and does not give us a full picture, as it should sit upon a base of health and general physical preparedness. This is something my colleagues at the European Tour Performance Institute sought to establish with our probability of impact pyramid.

“Inherently, as CHS increases so does injury risk, as the player has to sustain the increased forces associated with swinging faster. To counter this when we plan to upgrade the engine size, we also need to build a well-balanced chassis. This means increasing the ability of the relevant tissues (i.e., muscles and tendons) and structures (i.e., bones) to tolerate load. The force magnitude at the lumbar spine alone is worthy justification for the inclusion of strength training.” – Simon Brearley

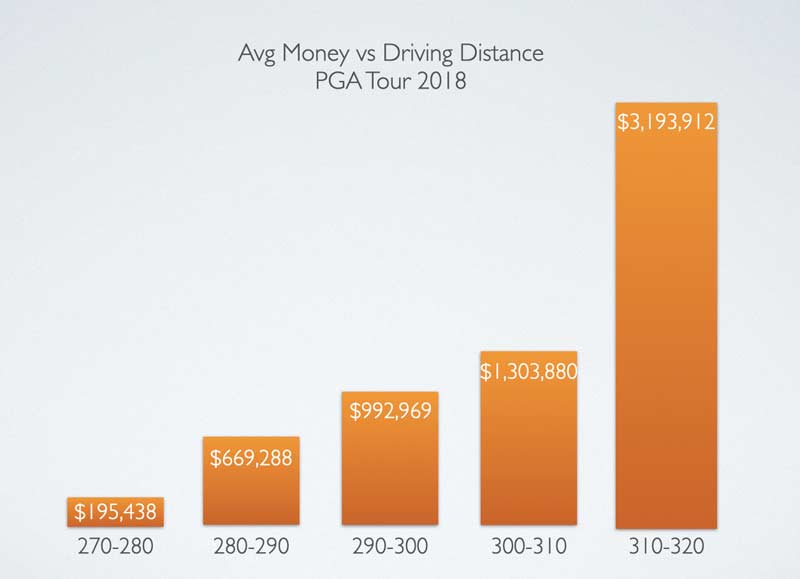

While strength and conditioning has a minor probability of impact on technical outputs, it can influence tactical ones. Hitting long can be a tactical option in golf, since taking longer shots is a bounded risk that leads to more prize money. We can look at recent PGA Tour data and see that driving distance and prize money earned are very much related.

In the modern golf performance arena, nothing can be left on the table. When I started working in golf, the biggest obvious gap was a lack of conventional physical training. Once athletes started employing even the most basic of strength training routines, club head speed improved.

Why do high-force exercises like squats, deadlifts, and loaded jumps seem to transfer so well to club head and ball speeds? Well, a key part of the relationship lies in the correspondence of execution time frames. The average pro golf swing is, in a sports context, a slow movement. The often-cited number we see is most sporting action taking around 0.2-0.3 seconds. The golf swing, however, has a longer time to completion, with 0.8-1.2 seconds often reported. That is a long time in a sporting context: nearly three to four times longer. People will quibble and talk only about the downswing, which obviously is very fast, but this is trying to use reductionism to protect a notion. The whole golf swing is a slow action in respect to other sports.

High-force exercises like squats, deadlifts, and loaded jumps seem to transfer so well to club head and ball speeds…because the whole golf swing is a slow action in respect to other sports. Share on XNow, time is absolutely crucial for producing a lot of force, and most squats and deadlifts travel at under 1 m/s versus most sporting actions being at 12 m/s. Most strength training at lower velocities and higher force production has a similar time frame—it’s generally considered slow. The ability to apply force vertically is crucial to swinging fast, and another common component of most conventional bilateral barbell training is improvements in vertical force. This helps what we call the anchoring effect (to be discussed later).

Why this; why now? Golfers are now starting to manifest the second order physicality that will produce more regular 130-mph club speeds, wanting to exploit any advantage this will be more normal than exceptional. Depending on what the R&A decide to do to slow play, as they recently argued that distance was hurting the game, I believe the ability to swing fast will be more important, not less, even with equipment changes.

So, all I need to do is train like a powerlifter? Wishful thinking, but no. There will of course be a point of diminishing returns where lateral, separation, and ballistic-based movements become important. Golf S&C has often emphasized these “specific” swing optimization approaches over a base of general preparation. I would argue possessing robustness and highly developed force-producing capacities allows specific approaches to be more effective. You cannot optimize a system that is not robust. Club head speed is a multifaceted thing, so many different factors go into it. But we can control some of those variables.

I mentioned in a previous article that roughly “80% of golf injuries are overuse-related. With this in mind, many golfers’ first port of call in supplementary training is a well-meaning physiotherapist who will often deal with the issue at hand, but not steel the athlete against its reoccurrence. Physiotherapy’s dominance in the sport can be witnessed when a golfer’s go-to piece of equipment after their clubs is their foam roller.”

I also mentioned before that this has come from what I see as a twofold issue: a culture of golfers leaning on a physiotherapist to inform their performance-related training and golfers’ flawed perceptions of strength and conditioning orthodoxy. Before I receive angry letters from physios, I respect the work of physiotherapists and call many friends and colleagues. They have a wheelhouse of responsibility that I cannot even imagine contending with.

So why has this situation come about? Well, my opinion is that many golf athletes only take supplementary strength work on board once they have been injured, and not before. Thankfully, many forward-thinking therapists now explore strength and conditioning as an avenue for injury reduction, especially when evidence dictates that these overuse injuries can be reduced by half with strength training.

When it comes to training for golfers, I usually suggest 1-3 reps, and probably no more than five, with varying loads depending on whether you want to achieve maximum velocity, power, or strength. Why? The golf swing is a very short duration, high-power, explosive activity clocking in at around 7,500 N in a full swing. (Keep in mind this force measurement is from a 1990 study, so it may be higher still.) To most strength coaches, this is considered pretty ordinary, but in the golf world it’s positively unorthodox.

As mentioned earlier, in the gym, training occurs at much lower velocities than it does during an actual sport. For comparison, the average punch is around 10 m/s, whereas the average dynamic effort bench press may only reach 0.8-1.0 m/s. A golf swing of a club travelling at 100 mph will be 44 m/s (very fast). The theory of dynamic correspondence suggests that as we approach a competition, velocity must increase to make the nervous system more specific in the way it produces force. Golf fitness has often put the figurative cart before the horse, focusing on specific velocity-focused or special strength methods ahead of general ones.

Golf fitness has often put the figurative cart before the horse, focusing on specific velocity-focused or special strength methods ahead of general ones, says @WSWayland. Share on XAs strength coaches, we know the attainment of general physical qualities can enhance sport performance in some individuals—particularly beginners. This is why novel modalities that force better bracing and ground interaction can yield positive outcomes at least initially. Once time goes on, training modalities focused on more specific exercises may, in fact, be needed for the continuing improvement of optimal transfer to more advanced athletes. This is where high-velocity peaking, contrast complex work, intent, etc. can be particularly useful, turning gym time into real-world performance statements. Real strength is the responsibility that many golfers and their coaches abdicate, so there is an opportunity for improvement that they are now starting to discover.

I am not a golf coach. My athletes do not come into the gym to practice golf—they come to build physical capacities that transfer well to golf. Getting stronger and gaining mass are the two most impactful things, from a general physical standpoint, a rotational power athlete can do, and that is what we are here to help with.

I’ve outlined the importance of strength. However, mere strength alone is only one facet of what we can affect to improve club head speed; club head speed being a key metric in the chase for distance. Most golfers need to raise the floor (get strong and robust) before they can lift the ceiling (optimize their speed).

There are other ways golfers can achieve this, and in a sport where 1 mph more in speed can equal a few yards, they are certainly not trivial. These approaches are:

- Gaining mass

- Complex or contrast methods

- Intent-based methods

- Swing optimization using GRF

Gaining Mass

One the most common concerns I hear in golf is the fear that an athlete gaining size will hurt their swing (baseball athletes worry about this as well). Both experience and research indicate the opposite. When golfers gain mass, we generally see a CHS improvement. It is important, however, that the mass gained is muscle; as they say, you can’t flex fat.

Becoming “bigger and stronger” helps with this in two ways:

- The increased muscle mass increases the player’s ability to produce ground reaction force—the basis of the force a golfer can utilize during their swing.

- The overall increase in body mass creates a greater anchoring effect, which helps the golfer remain stable throughout the swing.

The next point I usually get is an anecdote about how “so and so” got bigger, and it hurt their swing. There is a grain of truth to this if you take up bodybuilding to the exclusion of everything else. Then yes, your golf will probably suck.

We are currently seeing in golf what can only be described as the “Bryson Effect,” named after Bryson DeChambeau, the 2020 U.S. Open winner, whose weight gain, strength training, and club head speed improvements were well publicized. As golf is very peer-oriented, you will now see a pivot toward mass gain and athleticism by practitioners who in the past largely ignored their importance.

As a result, there has been an effort to try to explain the mass relationship in golf performance, and the equation used constantly is force = mass x acceleration. But this explanation is often misapplied scientism, with heavy focus on just the mass part. Even some of my favorite strength and conditioning experts have fallen into the trap of making this gross simplification.

F=ma is more of a linear concept, while most of the golf swing involves rotation. F=ma is part of the complex movement of the golf swing; it doesn’t explain what we see with Bryson’s swing. F=ma is a linear equation; the golf swing is rotational and requires an angular equation:

- Angular impulse τAΔt &

- Angular momentum L=Iω

Why? Well, during the golf swing:

- The club accelerates through angular impulse, increasing angular momentum of the body-club system without a sequential motion from the proximal (trunk) to distal (arm) segments; and

- Gaining large trunk angular momentum after the middle downswing is essential for achieving fast CHS. This key point is added mass anchors the athlete, allowing them to manipulate angular momentum further. Combine that with greater GRF manipulation, and that’s why mass matters so much.

This is not a full explanation of the complicated physics of the golf swing, as that sits well outside the scope of this article. And most golfers probably do not think about the detailed physics. Why? Because they apply and manipulate the variables implicitly.

One such way is by gaining mass, for instance. The others are how that mass is distributed and how angular velocity is generated. Part of the issue is that f=ma is such a neat equation it is very easy to dish out. Consider that one of my athletes swings very fast for a professional. He has recorded club head speeds of 135 mph, and he only weighs 205 pounds versus Bryson’s 240 pounds. If mass were so influential, he would just need to gain more weight to hit it even faster. Athletic muscular golfers yes; sumo-sized golfers, however, no.

I am breaking a rule I like: “Never engage in detailed overexplanations of why something is important: one debases a principle by endlessly justifying it.” – Nassim Nicholas Taleb

Biomechanics nerds will still find this explanation inadequate, but this isn’t written for solely biomechanists.

The nutrition of gaining mass goes well beyond the scope of this article, and there is years’ worth of information available all over the internet. The point is that, while a simplistic answer to the mass issue in golf is to just gain more weight to honor the mass element of the f=ma equation, nothing is ever that simple. How you use your mass and how you accelerate are equally important.

Complex or Contrast Methods

Earlier this year, I started toying with second-generation contrast training for golf. For the longest time, I’ve advocated that getting fast swingers faster has almost always been a result of getting them stronger. Often this is the lowest-hanging fruit. What do we do, however, with golfers who are “strong enough”? This is the time to apply swing-specific strength strategies. Most golf fitness approaches prize this first over robustness-oriented general strength training.

Getting fast swingers faster has almost always been a result of getting them stronger. So with golfers who are ‘strong enough,’ it is the time to apply swing-specific strength strategies. Share on XI’ve been a long-time advocate of French contrast training, making use of potentiation phenomena. To quote Joel Smith, “Barbell training delivers the coordinative mechanisms expressed in powerful movements,” when we marry it with an unloaded plyometric, a high-speed lift, and finally a very high speed plyo or accelerated movement, each potentiating the next. The idea of ascending correspondence means we can tailor our drills to better match our sport. So, we shift from general correspondence (least specific) to dynamic correspondence (most specific) throughout the course of a contrast sequence.

[vimeo 502365174 w=800]

Video 1. Ascending correspondence affords us overlapping potentiation and a smart way to concurrently train multiple qualities, which is crucial for time-poor golf athletes.

French contrast works acutely and chronically. A French contrast session looks something like this:

- Heavy partial-range lift or isometric for 1-3 reps.

- Rest 20 seconds.

- Force-oriented plyometric exercise, such as a depth jump.

- Rest 20 seconds.

- Speed-strength-oriented lift for low to medium reps, 2-5 typically.

- Rest 20 seconds.

- Speed-oriented plyometric exercise of higher repetition range.

- Rest 2-5 minutes and repeat.

This method has proved pivotal in helping my athletes be more explosive, jump higher, and see this transfer in a broad sense. But golf is a sport that can benefit from that acute potentiation to improve swing speed.

Thus, by taking this mix of coordinative improvements and nervous system potentiation, we can acutely and chronically improve club head speed. I use two approaches:

Version 1 – Simply modified French contrast

- Heavy partial-range lift or isometric for 1-3 reps.

- Rest 20 seconds.

- Force-oriented plyometric exercise, such as a depth jump.

- Rest 20 seconds.

- Speed-strength-oriented lift for low to medium reps, 2-5 typically.

- Rest 20 seconds.

- Speed-based swing using lighter speed stick 5 reps. Maximum intent!

- Rest 2-5 minutes and repeat.

Version 2 – Joel Smith second-generation

- Heavy partial-range lift or isometric for 1-3 reps.

- Rest 20 seconds.

- Force-oriented plyometric exercise, such as a depth jump.

- Rest 20 seconds.

- Speed-based swing using lighter speed stick 5 reps. Maximum intent!

- Repeat sequence once more, then rest.

I usually organize these into either vertical contrast or lateral contrast depending on the needs of the individual. Generally, as the athlete gets strong, their mastery of vertical force production means we can dig into more nuanced horizontal force production.

[vimeo 502368044 w=800]

Video 2. Vertical force expression is crucial in golf since it has a strong correlation to clubhead speed, and you should train it accordingly.

This way, we move from lowest to highest velocity in sequence. A swing radar or any speed tracker can keep intent high and also be used for a quality drop-off approach to maximum speed swing practice.

[vimeo 502369298 w=800]

Video 3. Once athletes have improved their vertical force expression, they can explore lateral and horizontal expression in either specific or nonspecific contexts.

I am careful to emphasize that this approach is a constrained and limited one. Something I stressed on Twitter recently was: “Swing specific speed strategies work but peak out very fast, as it’s a small bucket that fills quickly.” This is obviously in context of the broader approach of foundational physicality. I’ve found its usefulness diminishes after 4-6 weeks, usually with a flattening of improvement or staleness in terms of subjective feedback from the athlete.

Once a knife is sharp, it’s sharp—we don’t want to wear it down to the hilt. This means you will see shorter acute improvements from this type of approach. Keep monitoring club head speed and ball speed, and if the needle isn’t moving, then it’s probably time to shift your approach.

Intent-Based Methods

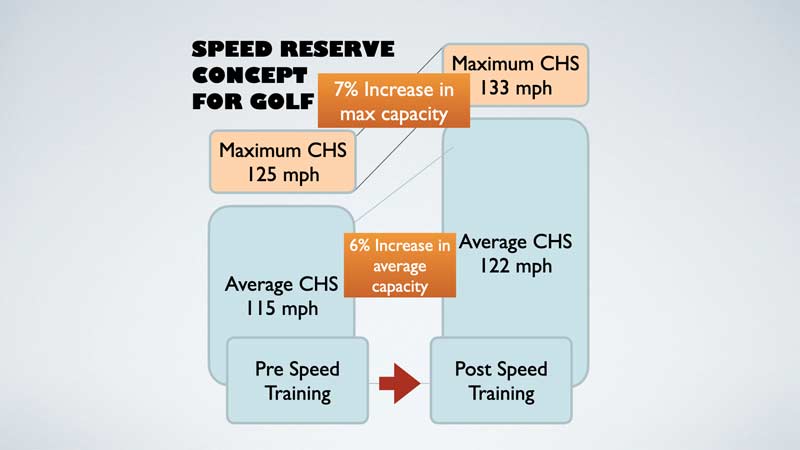

How many speed swings, coach? I get this question a lot, and I am becoming less fond of prescribing strict numbers for speed swings. Increasingly, autoregulatory approaches give us the best results. We have been having a lot of success with speed-based drop-off strategies to get our faster swingers’ speed ceilings even higher. Speed reserve is an important concept and utilizing the concept is one way to raise the ceiling.

“The Speed Reserve effect is real. We can condition our athletes through other means. If we help an athlete raise their maximal velocity, sub-maximal efforts become less metabolic costly. Similar to the idea of raising 1RM in a lift.” – Zach Higginbotham

The aim is, in short, to make those average swings better. When you are averaging what your opponents can max out on, it is a huge advantage that you should exploit.

As I stated earlier, we used a number of contrast and complex protocols to implement this. Cueing intent is crucial—think of it less as a golf swing and more like a numbers game. There is no ball strike here to worry about. Basically, we stop once we drop past a set threshold of speed.

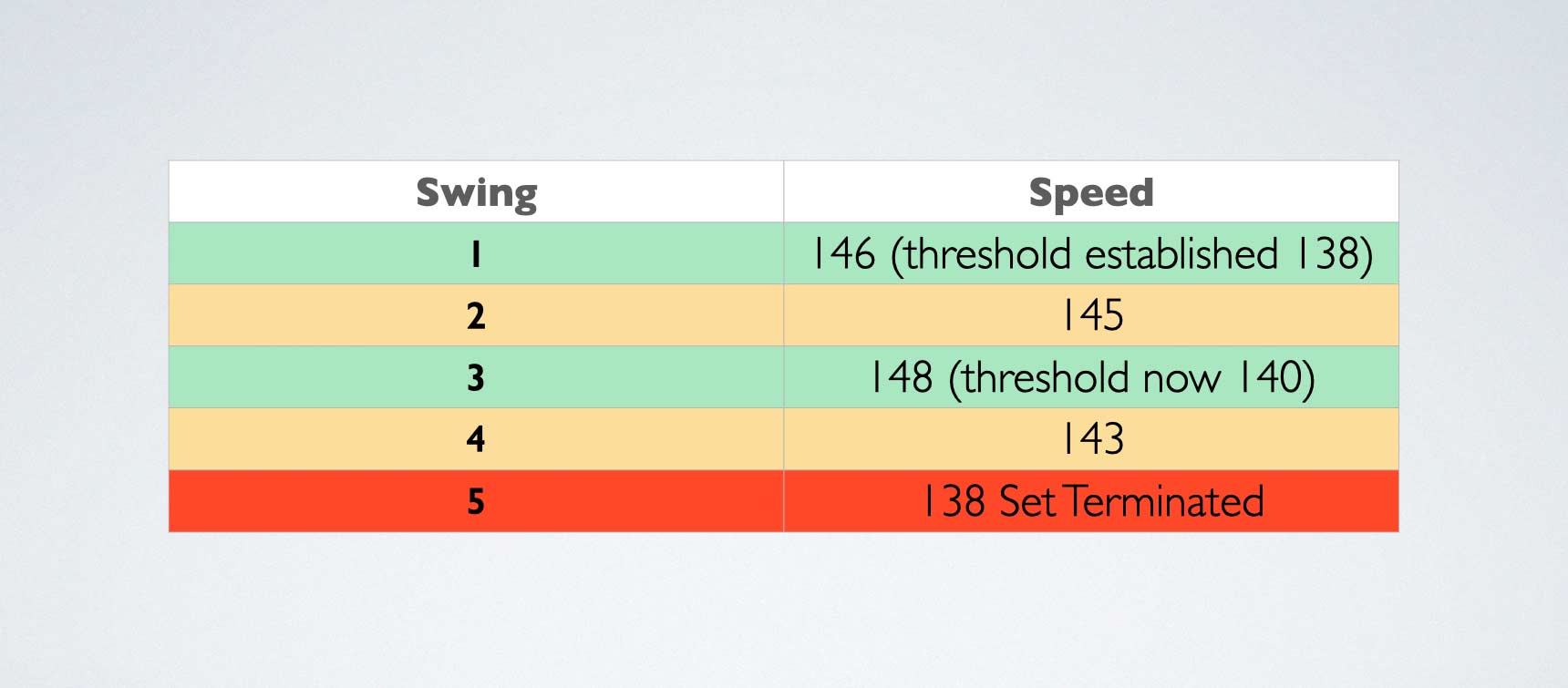

This is not dissimilar to velocity-based drop-off work we might do with velocity-based training, but the set termination threshold is much tighter. I have found around 5% works well. The protocol is to perform a swing every 5-15 seconds. Normally I encourage athletes to perform this on the range. Verbal cueing, intent, and freshness are all important to making this work. Below is an example table.

We stop the set after 5% drop-off and use the highest value of all sets to act as a benchmark. If the 5% drop-off is exceeded on the first swing versus the previous best, we terminate the activity. Usually we can get 3-4 sets of anywhere from 20-30 total swings.

[vimeo 502371292 w=800]

Video 4. Speed drop-off swinging is effectively a form of high-quality cluster training and benefits from micro rests between attempts to keep movement quality high.

I have found the club type/weight is probably not important, but what seems to be a sweet spot is around 10-15% higher speeds than with a conventional driver to get the most out of overspeed approaches. As mentioned in the past, acute and chronic gains from this level off fast.

Using GRF to Guide Swing Technical Intent

While the strength coach guides the improvement of an athlete’s force production and rate of force production, in the most general sense, there is occasion when specific exercises directed by the appropriate use of GRF data can influence the use of special exercises. Three-dimensional force platforms allow insight into GRF patterns in the swing and having the ability to produce a lot of force is not the same as using it well. While I do not have 3-D platforms myself, my athletes (like a lot of golfers) have a cadre of professionals who they can see for objective input. It’s then my job to decide if it’s something for their technical coach to address or an issue that I can deal with from a constraint-led approach.

[vimeo 502372564 w=800]

Video 5. By using 3-D GRF data, we can create drills specifically suited to the individual athlete and their specific strengths and weaknesses in the swing.

For instance, here is an athlete who needs to work on more lead leg drive and extension based on GRF swing data. He needs to push through the toes and almost hop back to add more force on the downswing. We devised two intensive contrast exercises, one with a 2-kilogram med ball and the other with a slightly heavier club. The idea here isn’t pure swing replication but smart overload of the desired element of their technical execution—something that Stefan Jones has mastered with cricket athletes.

You cannot optimize a system that is not robust, says @WSWayland. Share on XThe caveat here is that, in this example, our golfer is very robust, and as I’ve said before, you cannot optimize a system that is not robust. While similar to the fault-finding approach of the past in “golf fitness,” I am of the opinion most golfers cannot make the most of that approach because they lack the physical resources to do so.

First General, Then Specific Approaches

If you have a golfer who is particularly strong, and you feel they can get the most out these sorts of approaches, give them a try for some acute CHS gains. These approaches can also be appropriated by athletes in any rotational sport, and I use a similar approach with my combat athletes to improve striking power.

Golf professionals are now starting to grasp the fact that golf fitness has often sought overspecialized approaches to solving performance problems, or the aforementioned cart before the horse situation. Once a golfer has spent a few years getting under the bar, these specialized approaches can be inserted into the training rotation for best effect.

Since you’re here…

…we have a small favor to ask. More people are reading SimpliFaster than ever, and each week we bring you compelling content from coaches, sport scientists, and physiotherapists who are devoted to building better athletes. Please take a moment to share the articles on social media, engage the authors with questions and comments below, and link to articles when appropriate if you have a blog or participate on forums of related topics. — SF

References

Tilley, N. and Brearley, S. “How the best golfers in the world are using Strength & Conditioning to elevate their performance.” British Journal of Sports Medicine. August 12, 2020.

Wells, J.E., Charalambous. L.H., Mitchell. A.C., et al. “Relationships between Challenge Tour golfers’ clubhead velocity and force producing capabilities during a countermovement jump and isometric mid-thigh pull.” Journal of Sports Sciences. 2019;37(12):1381-1386.

Brearley, S., Coughlan, D., and Wells, J. “Strength and Conditioning in Golf: Probability of Performance Impact.” 2019.

Brearley, S. and Tilley, N. “What Should Golfers Do in the Gym?” Golf & Health.