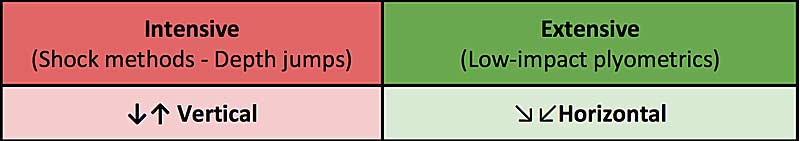

Derived from the work of Dr. Yuri Verkhoshansky, the terms intensive and extensive have increasingly been applied in the programming of plyometrics. These two labels are used to categorize plyometric movements by the intensity those movements yield on the body.

While this can be very useful in providing coaches with a way to categorize these movements, it becomes pretty obvious when we divide up our training that smaller, less impactful movements can be done at a much higher volume than our high-impact (shock method) variations. The split starts and ends there when it comes to categorizing plyometric movements, but with such an array and variety in plyometric landings, questions arise.

From my own coaching and research experience with plyometrics, this framework is not enough to provide others with the tools to build a program around dynamic movement development. Below are five reasons that explain why this is the case.

1. How Do We Determine “Intense”?

The intensive vs. extensive divide derives from a split between shock methods (depth jumps) and what Verkhoshansky termed “low-impact” plyometrics, where the angular vector of force effort has more horizontal coupling than the vertical angular vector of high-impact plyometrics. Interestingly, some research has suggested vertical angular forced movements don’t always produce higher-intensity landings than their horizontal counterpart1.

Do you know the difference in ground reaction force (GRF) between a depth jump and continuous hops?

Coaches and athletes need to understand the differences in landing forces when it comes to different angles of momentum and how that influences landing forces and loading patterns.

Potential issues with the split in angular momentum:

- Research suggests that hopping (unilateral landings on the same leg) has significantly high GRF2, but in some cases is deemed extensive.

- Unilateral and bilateral differences are overlooked when comparing the two movements mentioned above.

- Ground contact times (GCTs) aren’t considered half as often as GRF among coaches when plyos are divided between intensive and extensive. Highly dynamic movements such as bounding or leaping (bilateral landings) can possess very short GCTs, which in turn could be due to the effective coupling through the musculotendinous unit (MTU). This subsequently also produces very high GRF that could be deemed intensive! To an extent, it is difficult to drive fast GCTs without delivering high GRFs.

2. Differences in Athlete Type

Differences between athletes can play a major role in how they deal with exercise intensity.

- Neurally driven athletes may find locomotive plyometrics like bounding for distance relatively easy on the body, but also find vertical angular-driven movements such as depth jumps very intense.

- Concentrically driven athletes will tend to be the opposite, finding force expression easier on them than high volumes of more locomotive horizontal plyometrics.

2.1. The Unilateral and Bilateral Divide

Similar to athlete typing, there can be a potential divide in how athletes execute unilateral and bilateral landings.

- I have often seen (but it’s not always the case) that concentrically driven athletes will favor bilateral movements such as leaping (bilateral landing and takeoff) due to longer push-off phases.

- Neurally driven athletes may prefer unilateral landings that cover ground, as they’re able to utilize more tendon reflexes stored in the series elastic component (SEC), as opposed to longer muscular contracting movements.

Note: This may not be the case with all of these athlete types, as some will just optimize their landing strategies to best fit their type (for example, neural athletes may utilize a much shorter coupling effect for optimal jump height during a depth jump).

With the examples above, we have an athlete who is well adapted for this intensive and extensive format, while the other may struggle to get the training exposure you programmed for. Therefore, the phrases “intensive” and “extensive” plyometrics become hard to use when two athletes might experience different responses from the same stimulus.

3. Breaking Down the Variety Among Extensive Plyometrics

Although there are issues with the intensive category, coaches should find it simple to recognize that it should only include movements in around the top 10% of highly demanding landings, often with the highest GRFs.

The extensive side can become very broad in that it fills the other majority of “plyometric” movements under the top percentile of intensive plyos. This therefore leaves us with some relatively intense movements as seen below:

Video 1. Ping: Hops for distance

Video 2. Light: Leaps — at the other end of the spectrum!

As you can see in the two videos, these movements are significantly different in landing forces and GCT. It is understandable that you can use less-intense movements to expose athletes to a higher-volume stimulus, but ask yourself these questions:

- How intense are these movements I’m using for each individual?

- How close are they kinematically to the intensive plyometrics I’m programming?

- Most importantly, am I using the same volume for both extensive examples?

These questions should help you select and program the appropriate movements to elicit the training adaptations that you wish for. In my opinion, if you are not posing these questions, the potential for issues to arise will increase. Being critical of every layer of your training could be the difference between a well-timed peaking phase and tipping over the edge into potential injury.

Being critical of every layer of your training could be the difference between a well-timed peaking phase and tipping over the edge into potential injury, says @mcinneswatson. Share on X4. Intent

Intent is an important factor to consider when you’re dividing intensive and extensive movements. Usually, when an athlete has established a considerable background of plyometrics, they develop greater pre-activation methods that can increase their capacity to drive intent with dynamic landings.

Inexperienced athletes lack the neural control and skills learned from thousands of landings. This often shows when athletes are striving for maximal height and/or distance but end up stamping the ground (which tends to bleed all the force they’re producing into the ground, equaling longer GCTs and poor concentric output) or being highly tentative and absorbing most of the forces through joint distortion. Both types of inexperienced athletes struggle to control intent not only within their landings, but with all dynamic ground strikes.

Remember: All movements considered “plyometric” are highly dynamic and do not come without high force and shock upon the body, so make sure your athletes are well prepared before cueing for any kind of maximal intent.

The skills athletes need to learn to deliver the intent you need for dynamic landings are:

- Heightened landing precision for foot placement.

- Increased joint stiffening speed = faster coupling of eccentric to concentric phase.

- Subsequent faster GCT.

- Greater locomotive capacity to maintain velocity and/or utilize force.

With the skills and ability to deliver greater intent, many extensive movements can become very intense. Examples below show the same movement in two very different variations.

Video 3. Light: Hops. As you can see, this unilateral landing pattern shows small, cyclical landing with relatively low GRF (typical extensive plyometric).

Video 4. Ping: Fast Hop – High Hop. This variation shows a fast, accelerated hop to initiate a highly loaded eccentric phase to the second landing, propelling the athlete vertically. There is a significantly higher GRF and loading pattern through the lower extremities and posterior chain (typical extensive plyometric).

The second variation (Ping: Fast Hop – High Hop) clearly has the potential to be very intense in nature due to the driven intent of the fast hop to deliver a much faster eccentric loading rate (something typically found in hopping: unilateral, unipedal landings). If an athlete is ill-prepared to deliver this kind of intent, then a whole host of issues can arise. So, when you have extensive movements that are programmed for intent, consider the differences and level of development required for this so-called “submaximal” movement.

5. Issues with Extensive to Intensive Programming

The typical strategy of implementing plyometrics with the extensive and intensive divide is to move exactly in that way: Mapping the year out to start with extensive and become more intensive, often with a general to specific strategy as athletes gets closer to competition.

While this is logical, in some cases (beginners or underdeveloped athletes) we have a large cohort of athletes being subjected to the plyometric version of the long to short sprinting model that coaches are now critical of. As we garner further evidence year on year that suggests specificity to our events (or in this case, GRFs, GCTs, and multiple other specific parameters we see during competition) is critical and often requires regular programming throughout the year, we must question these ideologies.

If we use the extensive to intensive model, then similar issues that appeared in sprinting with the long to short model may arise. Where some athletes may thrive off this kind of programming, the diversity of the athletic population may mean other methods are more suitable. There are obviously many ways in which you can program plyometrics, but it is worth considering the impact of a regular insert of more intensive movements. If sprinting and speed models consider the value of sprinting at specifically high speeds regularly, then why would plyometrics be any different—especially when sprinting is deemed plyometric?

If sprinting and speed models consider the value of sprinting at specifically high speeds regularly, then why would plyometrics be any different—especially when sprinting is deemed plyometric? Share on XNote: The general to specific methods are valuable, as you can subject the athlete to competition-specific loading patterns and GCTs without it being event specific. For example, a long jumper can use bilateral landings and still evoke intense stress on the lower extremities.

Okay, well, where next? What’s the solution to a better way of categorizing plyometrics?

Revisit my previous SimpliFaster post, Plyometric Training Systems: Developmental vs. Progressive. That article illustrates a great way to break down landing dynamics into four simple categories that you can supplement within any phase of training throughout the year to develop everything from reactivity and elasticity to mobility and stability. You will notice that most will be deemed extensive or Verkhoshansky’s “horizontal angular momentum” movements, and that none of the tiers are “shock method,” per se. Understand that the ping and medium tiers elicit great GRFs in very short time frames, and when performed unilaterally can warrant high stress upon the MTU. Movements like ping tier speed hops also drive a higher level of specificity toward events such as sprinting and locomotion during sport, which is arguably not seen in a bilateral depth jump.

I hope that these are some questions you can now ask about your plyometrics programming and whether you’ll tread carefully along the intensive and extensive divide. There is more to this training method then just fast and slow or heavy and light.

Since you’re here…

…we have a small favor to ask. More people are reading SimpliFaster than ever, and each week we bring you compelling content from coaches, sport scientists, and physiotherapists who are devoted to building better athletes. Please take a moment to share the articles on social media, engage the authors with questions and comments below, and link to articles when appropriate if you have a blog or participate on forums of related topics. — SF

References

1. Mero, A. and Komi, P.V. “EMG, force, and power analysis of sprint-specific strength exercises.” Journal of Applied Biomechanics. 1994;10(1):1-13.

2. Perttunen, J., Kyrolainen, H., Komi, P.V. and Heinonen, A. “Biomechanical loading in the triple jump.” Journal of Sports Sciences. 2000;18(5):363-370.

I’ve followed these developments from the Soviet Sports journal, Dr. Michael Yessis USA, to Starzynski Polish. This article is excellent; and it justifies safe progressive workloads.

Thanks Mike, appreciate the comment 🙂