[mashshare]

Jump squats have always had a place in performance training. That’s because the exercise is a variation of the popular and effective back squat. A jump squat consists of performing a traditional squat while moving at a high enough speed to leave the ground and jump in the air. Intuitively, it’s an effective performance training exercise because the movement is explosive and ballistic. What makes the jump squat even more appealing is that we can teach and learn it at the same time as the traditional squat, so it’s a two-for-one deal.

With the challenges that come from teaching and learning Olympic lifts, jump squats would seem to be a particularly good alternative because of their simplicity and effectiveness. The exercise does, however, have limitations and shortcomings that curb its training effects. Consequently, rather than being a core lift, it’s considered a supplemental one.

I’m going to discuss first what limits the jump squat from being a staple, go-to movement for performance training. Then, I’ll talk about how the limitations have been overcome so we can look at the jump squat as a staple movement when developing power, explosiveness, and speed.

Two Limitations of Traditional Jump Squats

1. High Impact Ground Forces

I was introduced to the jump squat in 1996 during my sophomore year of high school, which also happened to be the year I had the greatest strength gains in my life (on a per year basis). Beginning the previous year as a freshman, I had maxed out at 135 lbs. on the bench and power cleans and squatted 200 lbs.

By the end of my freshman year and the beginning of my sophomore year, I had increased my one rep maxes for the bench press and power clean to 240 lbs. and squatted 350 lbs. That was an incremental increase of 77% on the bench and power cleans and 75% on squats in a matter of a year. My incremental strength increases then started to slow down drastically following that initial burst—to say the least—which is normal.

During this period, even though my strength levels had skyrocketed, it was not until we started doing jump squats as part of our lower body regimen that I experienced a significant increase in my explosiveness, speed, and jumping ability. Unfortunately, those results were short-lived. After doing jump squats for about a week, the landing forces blew out my hamstring to the point to where it came off the bone. It was a serious injury, and I had to deal with the repercussions for years afterward. It also discouraged me from ever wanting to do jump squats again.

It makes sense that when you increase the amount of ground impact forces an athlete has to absorb, the risk of injury also increases. The nature of playing any sport means there’s going to be an inherent amount of impact and wear and tear the body will have to withstand. And high impact situations occur in any sport.

Theoretically, reducing the wear and tear or the ground impact forces in training will reduce the risk of injury. That’s because a lot of injuries are caused by the accumulation of the heavy workloads performed during training and competition.

As I learned the hard way, traditional jump squats put the body through enough substantial ground impact forces that they can lead to injury. Landing with the load on the lifter’s back sends the forces of the falling bar through the body’s center mass. One small breakdown in landing technique could cause a serious injury, as in my case. But even with the soundest landing technique, the increase in the volume of ground impact forces puts any athlete who performs the traditional jump squat at a higher risk of injury.

2. The Inability to Effectively Train a Balanced Mix of Speed and Strength Simultaneously

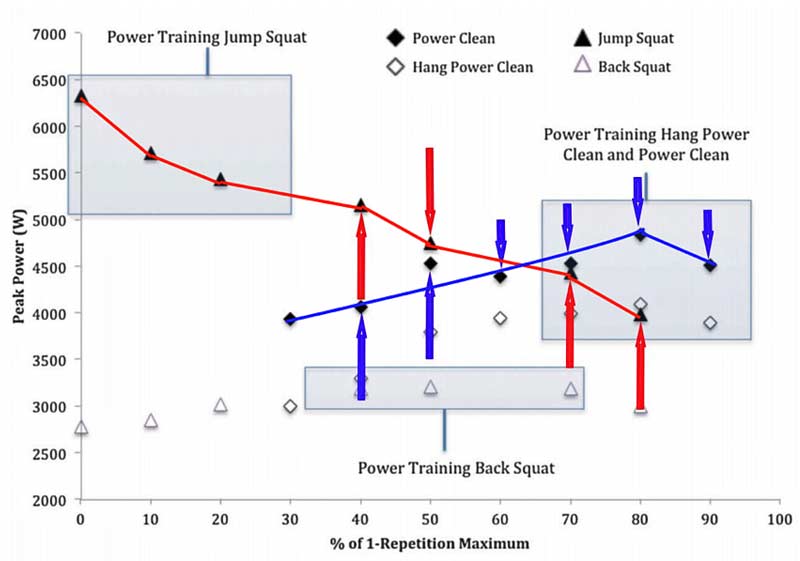

In studies that measure a jump squat’s power production, there is a very consistent trend. When the load exceeds about 30% of your one rep max, the power output starts to decrease (see Figure 1 below). Contrast that with Olympic lifts and their derivatives, where you can continue to increase power output up to about 70 to 75% of the one rep max. This means traditional jump squats (having to land with the loaded bar) are nowhere near as effective as training peak power output with heavy loads.

This limitation is a big reason why jump squats aren’t used as a staple lift in performance training; they don’t effectively train a balanced mixture of speed and strength, which comes from training power with heavier loads. This reduces the ability to develop functional power that translates to competition: when jump squatting with lighter loads, there isn’t enough strength training, and when jump squats are performed with heavier loads, there isn’t enough speed training.

In theory, mixing lighter jump squats with the heavier ones will train more balanced levels of speed and strength. But that’s a far less efficient use of time and energy than performing Olympic lifts, which train speed and strength simultaneously.

Another reason traditional jump squats are not as effective in training power relates to the high impact ground forces athletes have to absorb when landing the jump squat. As humans, we have a protective mechanism that preserves our body, or at least helps us avoid injuries. If the body naturally senses that we’re at risk of injuring ourselves, it subconsciously begins to shut down muscle activation to preserve itself.

A perfect example of this is the impact force of a tackle generated by an American football player in pads compared to that of a rugby player without pads. This video shows both scenarios—an American football player and a rugby player both giving their greatest amount of exertion to deliver the biggest blow. The rugby player is arguably bigger and more powerful than the American football player. But the American football player can deliver a far greater level of force (more than double) on impact than the rugby player.

A plausible explanation is that that the pads deactivate the football player’s self-preservation mechanism, as opposed to the rugby player whose lack of protection exposes them to the impact. You can do this experiment at home. Actually, I don’t want anyone to really try this, because it could lead to serious injury. So instead, imagine yourself mustering the force and speed to punch a brick wall as hard as you can, barehanded. Simply thinking about that pain and potential for injury makes me cringe. Next, imagine throwing the same hard punch against a softer surface, like a punching bag or a mattress.

We don’t need a measuring device to know which scenario would produce the greatest amount of force on impact. Unless you have no regard for your wellbeing, the greatest amount of impact force will be produced by the scenario where the body is not feeling a greater risk of injury.

The same self-preservation mechanism kicks in on jump squats when the lifter begins to place more than 30% of one rep max onto the bar. The lifter subconsciously reduces their effort during the concentric phase, knowing very well that what goes up must come down, and the landing will place the body under an immense amount of ground impact forces.

Basically, the body’s response is to diminish the impact by slowing down on the exertion (concentric) phase of the movement. The consequence of the subconscious shutting down of muscle exertion during the concentric phase is the limitation of speed and force levels that relate to power production with heavier loads.

Two Ways to Overcome the Limitations of the Jump Squat

1. Reduce the Jump Squat’s Ground Impact Forces

One excellent way to reduce the ground impact forces in jump squats is to eliminate having to land with the loaded barbell on the lifter’s back. The most straightforward way to do this is to simply release the barbell off of the lifter’s back so they don’t have to catch it. It’s something you can do on a platform with bumper plates. But when you want to do multiple repetitions one right after another, getting the bar back onto your shoulders will be a whole other challenge.

Video 1. Jump squats using the XPT, a power rack that catches the bar for the lifter at the top of the lift.

As an alternative, you can use a machine that has a safety catch. I invented the XPT, a power rack with a safety catch, for this very purpose. I experienced both the positive and negative effects that come from jump squatting. Can you blame me for learning from my past when I blew out my hamstring? That moment was a big motivator for me to come up with a way to do jump squats without having to land with the weight on your back. A power rack that can catch the bar for the lifter diminishes the negative effects of ground impact forces without compromising the positive effects of jump squatting.

2. Effectively Train Power by Jump Squatting with Heavy Loads

As established earlier, as loads greater than 30% of your one rep max are added to the bar, your power production incrementally decreases. The lifter’s self-preservation mechanism kicks in because the body senses the landing will increase their risk of injury.

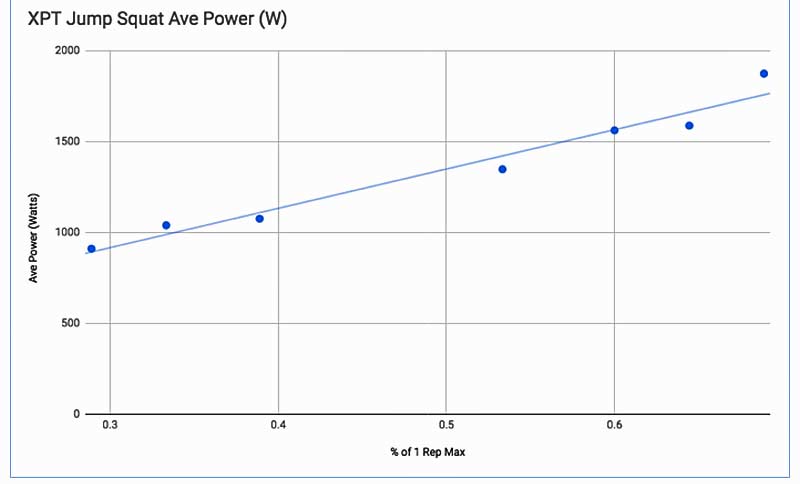

Turn the jump squat into a safe lift to effectively train speed and power simultaneously, says @BradyPoppinga. #jumpsquat #powertraining Share on XThis changes when the lifter has full confidence they won’t have to land with the loaded barbell on their back. As displayed in the graph below, peak power output increases when the lifter does not have to absorb the free-falling bar above the 30% one rep max threshold to about 80%. This adjustment turns the jump squat into a lift that trains both speed and power simultaneously, which arguably places it in the same category as Olympic lifts for developing power effectively.

From my experience, jump squatting with the ability to release the bar at the top of the movement and reducing ground impact forces, allows for optimal power production and development. I believe in the theories about jump squatting with no catch—not only because they make sense, but also because I’ve personally put them to the test.

For about six years, I’ve exclusively trained power by performing different variations of jump squats with varying loads without having to land with the loaded bar. I’ve increased my power production at a greater rate than any other point in my life. And bear in mind that this is six years removed from when I trained obsessively with Olympic lifts and other methods that are common in performance training while playing college and pro football.

It’s hard to argue with these results, particularly considering my age (39 years old ) and my injury history (three knee surgeries, including two ACL reconstructions, a herniated disc, and chronic knee pain), along with the wear and tear that comes from playing college football and almost a decade in the NFL.

Training power exclusively with jump squats without catching the bar transfers to the platform, says @BradyPoppinga. #jumpsquat #powertraining Share on XI’ve also concluded from my experience that exclusively working power through jump squats without catching the bar transfers to the platform. I don’t work power clean technique at all—I don’t even train on the platform. I only get on the platform to demonstrate the level of proficiency I’ve been able to attain just by doing jump squats with no catch.

Video 2. As you can see in the video, I was able to power clean 308 pounds three times in a row after training exclusively by jump squatting with heavier loads on the XPT.

In the video above, my technique is horrendous, and I’m sure all the technique gurus out there are cringing just watching it. But the reality is that I’ve never in my life been able to power clean 308 pounds that many times and at that speed. So from my experience, there’s no way I can sit here and say that jump squatting with no catch is not a comparable developer of power as Olympic lifting, especially with how well it translates to the platform.

Final Thoughts

What if a jump squat without catching the barbell is just as effective as Olympic lifts in terms of power development but with less wear and tear on the body? Ultimately, this is the question we have to answer.

What coach or athlete wouldn’t love to train optimal power and decrease injury risk? Imagine from a trainer’s perspective that teaching proper lifting was as simple as teaching the basics of the bench and squat and their variations and then adding explosive movements built on these fundamental movement patterns—like jump squats with no catch.

It would optimize the athlete’s learning curve and increase the proficiency of implementing a fundamentally sound training program. These are questions and ideas that should always be in the back of the mind of any trainer or athlete who is serious about getting the most from their time and energy invested, either in training themselves or others.

We no longer need to look at jump squatting as a supplemental lift. With time, and as we begin to pull back the layers, jump squatting will become a staple performance movement—as long as there’s a way to release the barbell at the top of the lift without having to catch it. That’s where the jump squat’s properties will evolve from a supplemental lift to a foundational performance-enhancing movement.

Since you’re here…

…we have a small favor to ask. More people are reading SimpliFaster than ever, and each week we bring you compelling content from coaches, sport scientists, and physiotherapists who are devoted to building better athletes. Please take a moment to share the articles on social media, engage the authors with questions and comments below, and link to articles when appropriate if you have a blog or participate on forums of related topics. — SF

[mashshare]