[mashshare]

During the academic year at my school, Mondays are the busiest training day of the week. Over the course of the day, 400 student athletes come in for workouts, with the bulk of them arriving during two high-traffic intervals: 6 am to 7:30 am and 2:30 pm to 5:30 pm. These are busy stretches, and with support staff limited to a grad assistant and a few undergrad interns, we have to lay out procedures almost perfectly so they run with precision. Otherwise, there’s too much downtime, and athletes end up cooling off while waiting to get the rack for their next set.

While I’m fortunate that we could have 24 people lifting in racks at the same time with another 24 spotting the lifters (accounting for 48 athletes), we typically have groups of 60-75 lifting at one time. That could be half of our football team or combined groups like the men’s and women’s hockey teams. Although it seems like there should be enough work for everyone to stay focused, having large groups of people lifting and staff members doing too many things at once, sometimes athletes decide to make their rest times longer than they should. What’s an overworked coach to do?

Programming rest activities for the athletes is the best of many things I’ve tried. While active recovery is not a new idea (Dr. Zatsiorsky talks extensively on this), we can look at recovery activities as ways to logistically control the flow of the room and spend enough time doing those extra—but easily skipped—pre-hab exercises.

We now have athletes set up in groups of three to four and, while one performs the main exercise, everyone else has a job to do, and no one should be screwing around and distracting others. Sounds good, right? It is. The hard part comes next. You have to decide which exercises are important to program and how much time the athletes need between sets.

What Makes An Exercise a Good Fit for Rest Intervals?

After a few years of programming rest exercises, I’ve been able to try a high percentage of my ideas. As you would expect, some worked well and others did not. I’m lucky now because my staff size has grown and I have other people who—because of their background or education—see different solutions that I never I could. That’s called diversity, by the way, and has been proven by history to be a good thing as long as you’re open to a range of ideas. The three areas where anyone (from undergrad intern to professional staff) can be creative are:

- Injury Reduction

- Grip

- Vision

Of course, we don’t try every idea that gets pitched in the staff meetings. We have to have a process to vet the ideas before we introduce them to the athletes.

Here are the four questions we ask before we try anything new.

Is this an exercise that athletes can easily do on their own, and is it unique enough to keep their attention?

Once upon a time, I was a staff of one (plus the occasional undergrad intern) coaching groups of up to 50 people. In that large of a setting, it’s really difficult to be effective coaching everyone at once, so I needed a way to keep half of the athletes busy and out of the way so I could spend time coaching more technical exercises. Out of necessity, I had people perform some drills that they could do on their own with minimal or no coaching at all—but it didn’t get off to a good start. I found myself coaching the recovery exercises more than the big compound exercises because people weren’t doing them correctly or not taking them seriously.

Do we have—or can we make—the equipment needed for this exercise?

A couple of my favorite shows growing up were the A-Team and MacGyver. In both of these series, the characters had to think of creative ways to use materials at hand to beat the bad guys and save the day. While we have some very specialized equipment that we use with our athletes, everything that they use for their rest exercises is homemade or found lying around the office.

Is this exercise so simple that you could coach a 5th grader to do it right?

The athletes take the lead on these recovery exercises. I teach a handful of them first, and their job is to teach the next group. Keeping that in mind, all the exercises have to be simple to set up and to teach. The fact that I’m working with college athletes with big, mature bodies doesn’t always mean they have big, mature brains.

Is this exercise going to allow the athlete to recover from their main exercise?

Since we’re talking about active rest exercise selection, be aware of the paradox of rest and exercise. You can blame my football coaching background for my deeply rooted aversion to people standing around during a workout, and my first few attempts at programming rest exercises were more exercise than rest. Those poor athletes needed a rest period after their rest period. I had to remind myself that tired and fatigued athletes only become more tired and do not improve. It was a blow to my ego when the rest exercises started looking more passive with people standing around, but the quality of their lifts improved, which is the important thing.

For an idea to go from the meeting room to a trial with athletes, we have to answer yes to all four questions. If it doesn’t, we work on it and adjust it until it passes our screening process. Once it does, we plug the new idea into some sample workouts to see how the athletes handle it. Be ready with a backup exercise, just in case. I’ve seen plenty of ideas pass all of the screening questions only to fail spectacularly when introduced in the weight room. It happens. Suck it up, learn from it, and move on. Now, let’s get into the recovery exercises.

Injury Reduction Exercises

There is more downtime in weight rooms than you’d expect. Say, for example, you have power cleans programmed for the athletes to do four sets of triples at 85% of their 1RM. How much rest should the lifter have? If you want them to mostly recover between attempts, 3-4 minutes rest would be about right. If you have lifting groups of three people, realistically each of the recovery exercises should take about 60-75 seconds. That way, you’ll account for 2-2.5 minutes of the lifter’s rest time with some extra time built in for them to get their head right before making an attempt. This should work out just perfectly.

The art, though, comes in deciding what type of focus you want for the recovery exercises. One of the hallmarks of strength and conditioning programs is that stronger athletes tend to get hurt less than weaker athletes.1, 2, 3I spend time addressing the injuries experienced by the athletes I work with. (The injuries rates on the chart below might be different than what the national averages show.) While we all have different names for similar exercises, and by no means is this going to be an exhaustive list, here are some types of exercise we use to address these common injuries.

Sport |

Most Common Injury Risk | Least Common Injury Risk | ||

Football |

Concussion: Manual and machine-based neck and jaw exercises |

Shoulder (A/C Joint): Rotator cuff and scapular stabilizer specific training |

Shoulder (G/H Joint): Band, dumbbell, and manual resistance internal and external rotation |

Lower Leg Muscle Strain: Proper warm up before entry into games |

Women’s Soccer |

Lower Leg Muscle Strain: Proper warm up before entry into games |

Concussion: Manual and machine-based neck and jaw exercises |

Low Back Strain: Proper warm up before entry into games and non-spinal loading exercises |

ACL Rupture: Single leg balance and strength exercises |

Women’s Volleyball |

Shoulder (A/C Joint): Rotator cuff and scapular stabilizer specific training |

Shoulder (G/H Joint): Band, dumbbell, and manual resistance internal and external rotation |

Finger Fracture or Dislocation: Pinch grip work |

Low Back Strain: Proper warm up before entry into games and non-spinal loading exercises |

Men’s Basketball |

Finger Fracture or Dislocation: Pinch grip work |

Ankle Inversion: Single leg balance and strength exercises |

Patellar Tendonitis: Proper warm up before practice and games, wearing zero drop shoes |

Lower Leg Muscle Strain: Proper warm up before entry into games |

Women’s Basketball |

Ankle Inversion: Single leg balance and strength exercises |

Finger Fracture or Dislocation: Pinch grip work |

Concussion: Manual and machine-based neck and jaw exercises |

ACL Rupture: Single leg balance and strength exercises |

Men’s Hockey |

Groin Strain: Band, dumbbell, and manual resistance abduction and adduction |

Shoulder (A/C Joint): Rotator cuff and scapular stabilizer specific training |

Concussion: Manual and machine-based neck and jaw exercises |

Low Back Strain: Proper warm up before entry into games and non-spinal loading exercises |

Women’s Hockey |

Groin Strain: Band, dumbbell, and manual resistance abduction and adduction |

Lower Leg Fracture: Consume dairy and weight training |

Low Back Strain: Proper warm up before entry into games and non-spinal loading exercises |

Concussion: Manual and machine-basedneck and jaw exercises |

Addressing any way to fix these common injuries is a good first step to keeping the athletes in the competition arena versus the training room. But for the athletes I work with, improving their performance is not limited to the typical exercises you would expect to see in a weight room.

Grip Exercises

As our athletes will tell you, I’m obsessive about the quality of their grip. It might be a reflection of society and the general avoidance of physical work, or it might be my belief that you’re only as strong as your hands, but many of our athletes come in as freshmen with embarrassingly weak grip strength. The overwhelming majority of team sports, however, require grip strength in some form, be it securing a tackle in football, holding onto a basketball, keeping a finger from jamming, or pulling a heavy deadlift without straps. Consequently, I place a concerted emphasis on grip strength.

You're only as strong as your grip allows you to be, says @CarmenPata. Share on XThe way I describe it, there are three types of grip strength: pinch, crush, and twist. Pinch grip exercises focus on using the thumb and fingertips to secure an object. For crush grip exercises, think of anything that you’re trying to close your whole hand around and, well, crush. Lastly, the twist grip uses your wrist to turn something forward or backward.

At the start of this article, I shared the four must-have qualities for a recovery exercise. Here is how I decide which grip exercises to program as recovery exercises.

Is this an exercise that athletes can easily do on their own, and is it unique enough to keep their attention?

Yes, most people have never seen anything like these exercises before they get into our gym.

Do we have—or can we make—the equipment needed for this exercise?

Yes, as strong as the athletes are, extra 45s, 25s, and dumbbells are always available.

Is this exercise so simple that you could coach a 5th grader to do it right?

Yes, all you have to say is “Pick it up until it drops. Make sure to have fast feel, though!”

Is this exercise going to allow the athlete to recover from their main exercise?

Yes, grip work will not fatigue the central nervous system, and no one will need an oxygen tank to help them breathe after a set. The notable exception is not to fatigue the athletes’ hands before deadlifts or any of the Olympic variations.

Since the grip exercises receive a yes on all of the questions in the screening protocol, try adding in one at a time with the people you work with. Try the pinch grip for starters, as a person can do it with a double overhand position. When they need a new challenge, move into the single overhand position.

Pinch Grip

To really work on the pinch grip, start with two sets of plates and put them together front to back. I begin our male athletes with two 45-pound plates and female athletes with two 25s. In our gym, we don’t have metal plates anymore, which is a blessing and a curse for grip work. The bumper-style plates are easier to grip (as the rubber is easier to grab than the smooth metal), but they’re also thicker than standard metal plates, making it more difficult for people with smaller hands.

- Whatever style plates you have, stand them up and then put the plates face to face (so the backs of the plates are facing out).

- Pinch the plates between your thumb and fingers and pick them up. For the first couple of runs, chalk will help with your grip, but as your grip improves, slowly wean yourself off the chalk.

- When you’re ready to step up to a new challenge, try the single overhand version of the plate pinch as shown in the pictures.

- The final and most difficult evolution of the plate pinch is to add movement to this pinch, in the version of a plate.

Video 1. Finishing a pinch grip exercise with a mic drop moment is not needed, but it’s deeply satisfying.

Crush Grip

Since a crush grip simulates closing your hand to make a fist and crushing anything in its way, you can use something as simple as a towel to train for it. Both of the examples below involve the athlete doing some type of pulling exercise. The only direction I give the athletes is to keep their grip on the towel—no wrapping the towel around their hand.

Video 2. Towel pull ups are about as easy as it gets. Simply hang two towels from a pull-up bar and start your reps from there.

Partner towel rows take a little more coordination since you’re pulling against another person and both of you must be in sync. I coach a three-second eccentric tempo with both people holding the towel in the same hand, which gives an angled pull. And as long as they keep their chests squared up, this drill also doubles as an anti-rotation drill for the torso.

Video 3. The partner towel rows provide an angled pull and double as an anti-rotation drill for the torso.

Twist Grip

For targeting the twist grip, the kettlebell bar twist is my go-to exercise. As you can see in the video below, we set a standard Olympic bar at shoulder height and tied a weight to a stretch-band while looping the other end around the bar’s sleeve. What you don’t see is a 45-pound plate on the opposite side counterbalancing the kettlebell hanging from the bar.

When I program this exercise, I explain that each rep will go up with wrist flexion (turning your palm down) and down with a controlled eccentric wrist extension (turning your palm up). For the next rep, just go the other way: extension then flexion.

Video 4. The kettlebell bar twist is my go-to exercise for targeting the twist grip.

These examples of the pinch, crust, and twist grip exercises give you a starting point for getting strong hands. Again, you’re only as strong as your grip allows you to be.

Vision Training Exercises

Finally, the last of my programmed rest exercises work one of the most overlooked aspects insports: visual acuity. Or, as I tell athletes, these drills will help them see better. Using basketball as an example, watch how much the players’ eyes move around looking at the ball, their opponents, their teammates, coaches, officials, or even the people in the stands. Their eyes are in constant motion and quickly change their focus. As strength and conditioning professionals, we do all sorts of work to help improve people’s speed, power, and stamina, so why don’t we spend time helping them track, focus, and identify their targets faster?

Some of our rest exercises work one of the most overlooked aspects in sports: visual acuity, says @CarmenPata. Share on XKeeping with the basketball example, it doesn’t matter how fast an athlete is if they keep visually losing track of the person they’re guarding—they won’t be on the court playing. If progressive overload is a way to force a super-compensation of muscle, then there should be a way to overload the muscles that control eye movement and focus the pupil. Before we get going too far, let me state the obvious: adding weights to the eyeball is not how you’re going to overload these muscles. What I’m suggesting is that you can fatigue these muscles by forcing them to move fast and adjust their focus quickly.

Like every other muscle group in the body, our eyes have a few main movement patterns which work in opposite relation to each other to stabilize the joint—or in this case, the eye. The main body movements are flexion and extension, internal rotation and external rotation, and protraction and retraction.

The eyes are the same. I’m not comfortable using the correct optometrist terms, so I’ll stick with the common terms of up and down, left and right, all the angles in between these, slight rotation to or away from the nose, convergence (cross-eyed) and divergence (bug-eyed). All of these movements come into play one way or another when the eyes focus on a target.

As your eyeballs move to see the target best, the colored part of the eye relaxes or contracts to change the amount of light that ultimately transmits to the back of the eye to the retina and then your brain “sees” what you’re focusing on. This description is an overly simplistic—yet accurate—portrayal of how our eyes focus, and it does have something in common with every other movement pattern the body produces: muscles make everything happen in sequence.

Since there are muscles involved in producing these movements, you can train the muscles surrounding and inside the eyes to become more efficient and faster in their movements, just like we do to help people run or jump. Here’s how I do it.

Eye Charts

I start with the most basic skill and have the athletes match letters and numbers from two sets of charts. One is smaller (4″x6″) held in their hand while the other is larger (8.5″x11″) and posted about 6-8 feet away from the athlete. Their job is to read their handheld card like a book (left to right and top to bottom) and then find the matching character on the far sheet as fast as they can.

When doing this sort of vision work, the athlete’s goal is to move their eyes as much as possible while specifically focusing on a target. We’ve had people do this while running their feet, doing some jumps, up-downs, or even switching cards during the set.

Another progression is to have them move the card or their body in different positions. To their right or left. Over their head or at their hips. Feel free to change the font size and colors to make it a bigger challenge. You can even do this with one eye closed. Let your imagination be your guide in how you want to challenge the athletes and overload the eye musculature.

Hand-Eye

Once people start getting good with the vision charts, the next step is to help them track an object as it moves in space. This is not something overly complicated. All I’m talking about is playing catch. Well, there is a twist—you need two different colored balls. In the video below, there are red and white lacrosse balls. Tell the athlete which hand is going to catch which colored ball. In the video, the athlete is supposed to catch the white ball in the right hand and the red ball in the left.

Video 5. The hand-eye catch exercise helps athletes track an object as it moves in space.

We start fairly easy, only going one ball at a time. Then, once the athlete has their rhythm, they turn 90 degrees toward me with their left shoulder pointing at me, but they still need to catch the ball with the correct hand. Lastly, the athlete turns 90 degrees the other way, so their right shoulder is pointed at me. This is a relatively easy progression.

Next, I throw both balls at once with high-low, both sides, and even a crossed-arm catching pattern. As with the vision charts, we do this with one eye closed or start with both eyes closed and opening on a “go!” call. These drills are to help the eyes focus on targets, not to help the person’s catching skills. Some people have never practiced catching drills before and will be discouraged quickly if you emphasize the catch. You should coach them up on their ability to see and react to the different balls.

Convergence-Divergence

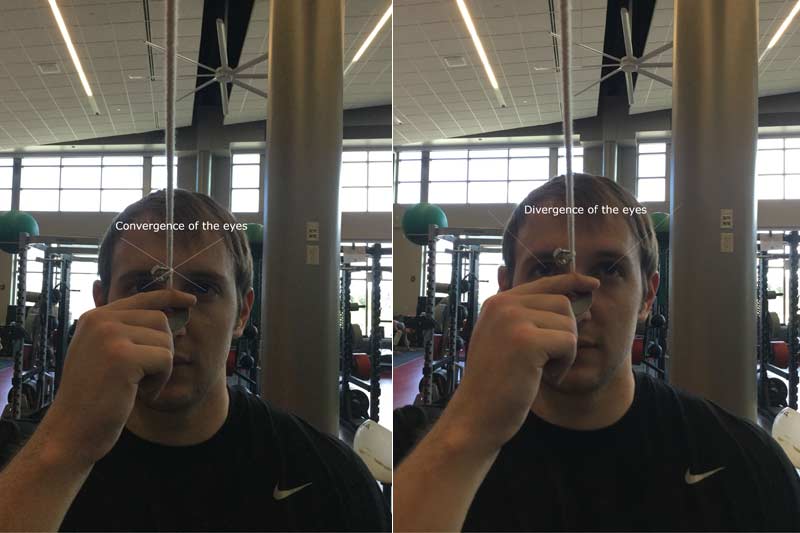

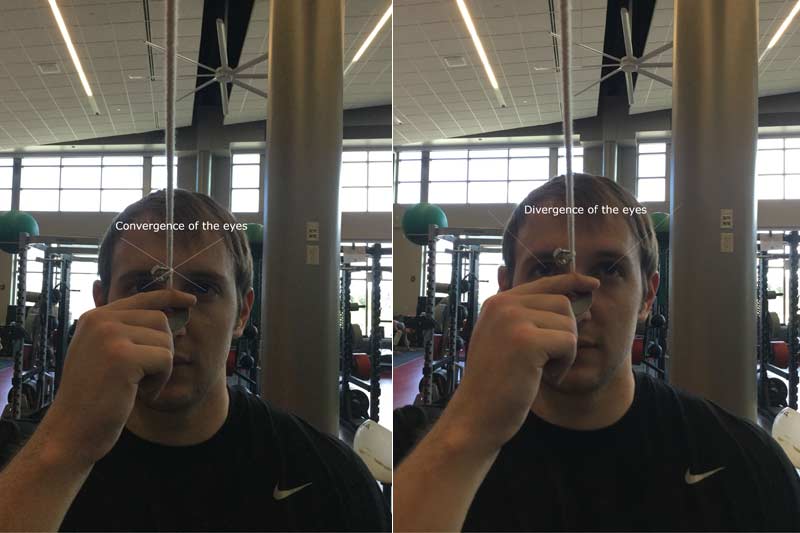

The last vision skill we teach is done with some high-tech equipment: a six-foot piece of string or rope, five ½ nuts, a one-inch washer, and a dedicated carabiner. To set this up, tie off the washer to one end of the string, loop the nuts through the string (so they don’t slide off) every foot or so, and then tie the other end of the string to the carabiner, which you secure to your rack. When the athlete is ready, they hold the washer on the top of their nose right between their eyes then step back until the string is straight.

Their goal is to either converge or diverge their eyes so they experience a blurry double-vision of the string crossing at the first nut. Once that happens, they relax their eyes to come back to normal and then converge or diverge their eyes at the next nut, working up the string. This is harder than you’d think, and if they’re worried about always looking awkward while doing this drill—well, they’re right about that, but no one is going to notice.

Make a Difference Where and When You Can

The overall idea behind these drills is to fill the athletes’ time with quality work and not just to keep them busy. Pre-hab, grip, and vision work are areas that I’ve been quick to overlook in the past but are vital to an athlete’s overall development. Like you, I’m naturally drawn to watching someone set their new squat max, or shave a tenth of a second off their ten-yard sprint time because it’s fun to watch and is something you can feel proud about being part of. Seeing someone set a new PR on their string target convergence drill is not something I’m going to ever post on social media or brag out to other coaches because it’s not that glamorous.

On the other hand, if you’re like me and believe you’ll get the greatest improvements in performance by attacking people’s deficiencies, then maybe you should celebrate these improvements. Say you already have a basketball player who is strong (a double bodyweight back squat), fast (a 1.6-second ten-yard sprint), and powerful (30-inch vertical jump). What more can you really do with this person that’s going to impact their performance?

If I was working with a person like that, I might simply try to keep them healthy, fast, and strong. But that doesn’t improve their performance on the court. Would helping their eyes move and focus faster on what’s happening on the court change their performance? What about making sure their hands are strong enough to hold onto the ball coming down from a rebound? Save your answers, these are rhetorical questions.

Seeing people improve and stay healthy are always my goals for athletes. Just because the improvements happen in a non-traditional exercise doesn’t change the fact they’re still getting better, and their training is making an impact when they compete.

Since you’re here…

…we have a small favor to ask. More people are reading SimpliFaster than ever, and each week we bring you compelling content from coaches, sport scientists, and physiotherapists who are devoted to building better athletes. Please take a moment to share the articles on social media, engage the authors with questions and comments below, and link to articles when appropriate if you have a blog or participate on forums of related topics. — SF

[mashshare]

References

1. Zouita, S. et al. “Strength Training Reduces Injury Rate In Elite Young Soccer Players During One Season.” Journal of Strength and Conditioning Research, 2016; 30(5): 1295-1307.

2. Hewitt, T. E., et al. “The Effect of Neuromuscular Training on the Incidence of Knee Injury in Female Athletes: A Prospective Study.” American Journal of Sports Medicine, 1999; 27(6): 699-706.

3. Alentorn-Geli, E., et al. “Prevention of Non-Contact Anterior Cruciate Ligament Injuries in Soccer Players Part 1: Mechanisms of Injury and Underlying Risk Factors.” Knee Surgery, Sports Traumatology, Arthroscopy, 2009; 17(7): 705-729.

3 Ways to Maximize Rest Intervals in a Lifting Session

[mashshare]

During the academic year at my school, Mondays are the busiest training day of the week. Over the course of the day, 400 student athletes come in for workouts, with the bulk of them arriving during two high-traffic intervals: 6 am to 7:30 am and 2:30 pm to 5:30 pm. These are busy stretches, and with support staff limited to a grad assistant and a few undergrad interns, we have to lay out procedures almost perfectly so they run with precision. Otherwise, there’s too much downtime, and athletes end up cooling off while waiting to get the rack for their next set.

While I’m fortunate that we could have 24 people lifting in racks at the same time with another 24 spotting the lifters (accounting for 48 athletes), we typically have groups of 60-75 lifting at one time. That could be half of our football team or combined groups like the men’s and women’s hockey teams. Although it seems like there should be enough work for everyone to stay focused, having large groups of people lifting and staff members doing too many things at once, sometimes athletes decide to make their rest times longer than they should. What’s an overworked coach to do?

Programming rest activities for the athletes is the best of many things I’ve tried. While active recovery is not a new idea (Dr. Zatsiorsky talks extensively on this), we can look at recovery activities as ways to logistically control the flow of the room and spend enough time doing those extra—but easily skipped—pre-hab exercises.

We now have athletes set up in groups of three to four and, while one performs the main exercise, everyone else has a job to do, and no one should be screwing around and distracting others. Sounds good, right? It is. The hard part comes next. You have to decide which exercises are important to program and how much time the athletes need between sets.

What Makes An Exercise a Good Fit for Rest Intervals?

After a few years of programming rest exercises, I’ve been able to try a high percentage of my ideas. As you would expect, some worked well and others did not. I’m lucky now because my staff size has grown and I have other people who—because of their background or education—see different solutions that I never I could. That’s called diversity, by the way, and has been proven by history to be a good thing as long as you’re open to a range of ideas. The three areas where anyone (from undergrad intern to professional staff) can be creative are:

- Injury Reduction

- Grip

- Vision

Of course, we don’t try every idea that gets pitched in the staff meetings. We have to have a process to vet the ideas before we introduce them to the athletes.

Here are the four questions we ask before we try anything new.

Is this an exercise that athletes can easily do on their own, and is it unique enough to keep their attention?

Once upon a time, I was a staff of one (plus the occasional undergrad intern) coaching groups of up to 50 people. In that large of a setting, it’s really difficult to be effective coaching everyone at once, so I needed a way to keep half of the athletes busy and out of the way so I could spend time coaching more technical exercises. Out of necessity, I had people perform some drills that they could do on their own with minimal or no coaching at all—but it didn’t get off to a good start. I found myself coaching the recovery exercises more than the big compound exercises because people weren’t doing them correctly or not taking them seriously.

Do we have—or can we make—the equipment needed for this exercise?

A couple of my favorite shows growing up were the A-Team and MacGyver. In both of these series, the characters had to think of creative ways to use materials at hand to beat the bad guys and save the day. While we have some very specialized equipment that we use with our athletes, everything that they use for their rest exercises is homemade or found lying around the office.

Is this exercise so simple that you could coach a 5th grader to do it right?

The athletes take the lead on these recovery exercises. I teach a handful of them first, and their job is to teach the next group. Keeping that in mind, all the exercises have to be simple to set up and to teach. The fact that I’m working with college athletes with big, mature bodies doesn’t always mean they have big, mature brains.

Is this exercise going to allow the athlete to recover from their main exercise?

Since we’re talking about active rest exercise selection, be aware of the paradox of rest and exercise. You can blame my football coaching background for my deeply rooted aversion to people standing around during a workout, and my first few attempts at programming rest exercises were more exercise than rest. Those poor athletes needed a rest period after their rest period. I had to remind myself that tired and fatigued athletes only become more tired and do not improve. It was a blow to my ego when the rest exercises started looking more passive with people standing around, but the quality of their lifts improved, which is the important thing.

For an idea to go from the meeting room to a trial with athletes, we have to answer yes to all four questions. If it doesn’t, we work on it and adjust it until it passes our screening process. Once it does, we plug the new idea into some sample workouts to see how the athletes handle it. Be ready with a backup exercise, just in case. I’ve seen plenty of ideas pass all of the screening questions only to fail spectacularly when introduced in the weight room. It happens. Suck it up, learn from it, and move on. Now, let’s get into the recovery exercises.

Injury Reduction Exercises

There is more downtime in weight rooms than you’d expect. Say, for example, you have power cleans programmed for the athletes to do four sets of triples at 85% of their 1RM. How much rest should the lifter have? If you want them to mostly recover between attempts, 3-4 minutes rest would be about right. If you have lifting groups of three people, realistically each of the recovery exercises should take about 60-75 seconds. That way, you’ll account for 2-2.5 minutes of the lifter’s rest time with some extra time built in for them to get their head right before making an attempt. This should work out just perfectly.

The art, though, comes in deciding what type of focus you want for the recovery exercises. One of the hallmarks of strength and conditioning programs is that stronger athletes tend to get hurt less than weaker athletes.1, 2, 3I spend time addressing the injuries experienced by the athletes I work with. (The injuries rates on the chart below might be different than what the national averages show.) While we all have different names for similar exercises, and by no means is this going to be an exhaustive list, here are some types of exercise we use to address these common injuries.

Sport |

Most Common Injury Risk | Least Common Injury Risk | ||

Football |

Concussion: Manual and machine-based neck and jaw exercises |

Shoulder (A/C Joint): Rotator cuff and scapular stabilizer specific training |

Shoulder (G/H Joint): Band, dumbbell, and manual resistance internal and external rotation |

Lower Leg Muscle Strain: Proper warm up before entry into games |

Women’s Soccer |

Lower Leg Muscle Strain: Proper warm up before entry into games |

Concussion: Manual and machine-based neck and jaw exercises |

Low Back Strain: Proper warm up before entry into games and non-spinal loading exercises |

ACL Rupture: Single leg balance and strength exercises |

Women’s Volleyball |

Shoulder (A/C Joint): Rotator cuff and scapular stabilizer specific training |

Shoulder (G/H Joint): Band, dumbbell, and manual resistance internal and external rotation |

Finger Fracture or Dislocation: Pinch grip work |

Low Back Strain: Proper warm up before entry into games and non-spinal loading exercises |

Men’s Basketball |

Finger Fracture or Dislocation: Pinch grip work |

Ankle Inversion: Single leg balance and strength exercises |

Patellar Tendonitis: Proper warm up before practice and games, wearing zero drop shoes |

Lower Leg Muscle Strain: Proper warm up before entry into games |

Women’s Basketball |

Ankle Inversion: Single leg balance and strength exercises |

Finger Fracture or Dislocation: Pinch grip work |

Concussion: Manual and machine-based neck and jaw exercises |

ACL Rupture: Single leg balance and strength exercises |

Men’s Hockey |

Groin Strain: Band, dumbbell, and manual resistance abduction and adduction |

Shoulder (A/C Joint): Rotator cuff and scapular stabilizer specific training |

Concussion: Manual and machine-based neck and jaw exercises |

Low Back Strain: Proper warm up before entry into games and non-spinal loading exercises |

Women’s Hockey |

Groin Strain: Band, dumbbell, and manual resistance abduction and adduction |

Lower Leg Fracture: Consume dairy and weight training |

Low Back Strain: Proper warm up before entry into games and non-spinal loading exercises |

Concussion: Manual and machine-basedneck and jaw exercises |

Addressing any way to fix these common injuries is a good first step to keeping the athletes in the competition arena versus the training room. But for the athletes I work with, improving their performance is not limited to the typical exercises you would expect to see in a weight room.

Grip Exercises

As our athletes will tell you, I’m obsessive about the quality of their grip. It might be a reflection of society and the general avoidance of physical work, or it might be my belief that you’re only as strong as your hands, but many of our athletes come in as freshmen with embarrassingly weak grip strength. The overwhelming majority of team sports, however, require grip strength in some form, be it securing a tackle in football, holding onto a basketball, keeping a finger from jamming, or pulling a heavy deadlift without straps. Consequently, I place a concerted emphasis on grip strength.

You're only as strong as your grip allows you to be, says @CarmenPata. Share on XThe way I describe it, there are three types of grip strength: pinch, crush, and twist. Pinch grip exercises focus on using the thumb and fingertips to secure an object. For crush grip exercises, think of anything that you’re trying to close your whole hand around and, well, crush. Lastly, the twist grip uses your wrist to turn something forward or backward.

At the start of this article, I shared the four must-have qualities for a recovery exercise. Here is how I decide which grip exercises to program as recovery exercises.

Is this an exercise that athletes can easily do on their own, and is it unique enough to keep their attention?

Yes, most people have never seen anything like these exercises before they get into our gym.

Do we have—or can we make—the equipment needed for this exercise?

Yes, as strong as the athletes are, extra 45s, 25s, and dumbbells are always available.

Is this exercise so simple that you could coach a 5th grader to do it right?

Yes, all you have to say is “Pick it up until it drops. Make sure to have fast feel, though!”

Is this exercise going to allow the athlete to recover from their main exercise?

Yes, grip work will not fatigue the central nervous system, and no one will need an oxygen tank to help them breathe after a set. The notable exception is not to fatigue the athletes’ hands before deadlifts or any of the Olympic variations.

Since the grip exercises receive a yes on all of the questions in the screening protocol, try adding in one at a time with the people you work with. Try the pinch grip for starters, as a person can do it with a double overhand position. When they need a new challenge, move into the single overhand position.

Pinch Grip

To really work on the pinch grip, start with two sets of plates and put them together front to back. I begin our male athletes with two 45-pound plates and female athletes with two 25s. In our gym, we don’t have metal plates anymore, which is a blessing and a curse for grip work. The bumper-style plates are easier to grip (as the rubber is easier to grab than the smooth metal), but they’re also thicker than standard metal plates, making it more difficult for people with smaller hands.

- Whatever style plates you have, stand them up and then put the plates face to face (so the backs of the plates are facing out).

- Pinch the plates between your thumb and fingers and pick them up. For the first couple of runs, chalk will help with your grip, but as your grip improves, slowly wean yourself off the chalk.

- When you’re ready to step up to a new challenge, try the single overhand version of the plate pinch as shown in the pictures.

- The final and most difficult evolution of the plate pinch is to add movement to this pinch, in the version of a plate.

Video 1. Finishing a pinch grip exercise with a mic drop moment is not needed, but it’s deeply satisfying.

Crush Grip

Since a crush grip simulates closing your hand to make a fist and crushing anything in its way, you can use something as simple as a towel to train for it. Both of the examples below involve the athlete doing some type of pulling exercise. The only direction I give the athletes is to keep their grip on the towel—no wrapping the towel around their hand.

Video 2. Towel pull ups are about as easy as it gets. Simply hang two towels from a pull-up bar and start your reps from there.

Partner towel rows take a little more coordination since you’re pulling against another person and both of you must be in sync. I coach a three-second eccentric tempo with both people holding the towel in the same hand, which gives an angled pull. And as long as they keep their chests squared up, this drill also doubles as an anti-rotation drill for the torso.

Video 3. The partner towel rows provide an angled pull and double as an anti-rotation drill for the torso.

Twist Grip

For targeting the twist grip, the kettlebell bar twist is my go-to exercise. As you can see in the video below, we set a standard Olympic bar at shoulder height and tied a weight to a stretch-band while looping the other end around the bar’s sleeve. What you don’t see is a 45-pound plate on the opposite side counterbalancing the kettlebell hanging from the bar.

When I program this exercise, I explain that each rep will go up with wrist flexion (turning your palm down) and down with a controlled eccentric wrist extension (turning your palm up). For the next rep, just go the other way: extension then flexion.

Video 4. The kettlebell bar twist is my go-to exercise for targeting the twist grip.

These examples of the pinch, crust, and twist grip exercises give you a starting point for getting strong hands. Again, you’re only as strong as your grip allows you to be.

Vision Training Exercises

Finally, the last of my programmed rest exercises work one of the most overlooked aspects insports: visual acuity. Or, as I tell athletes, these drills will help them see better. Using basketball as an example, watch how much the players’ eyes move around looking at the ball, their opponents, their teammates, coaches, officials, or even the people in the stands. Their eyes are in constant motion and quickly change their focus. As strength and conditioning professionals, we do all sorts of work to help improve people’s speed, power, and stamina, so why don’t we spend time helping them track, focus, and identify their targets faster?

Some of our rest exercises work one of the most overlooked aspects in sports: visual acuity, says @CarmenPata. Share on XKeeping with the basketball example, it doesn’t matter how fast an athlete is if they keep visually losing track of the person they’re guarding—they won’t be on the court playing. If progressive overload is a way to force a super-compensation of muscle, then there should be a way to overload the muscles that control eye movement and focus the pupil. Before we get going too far, let me state the obvious: adding weights to the eyeball is not how you’re going to overload these muscles. What I’m suggesting is that you can fatigue these muscles by forcing them to move fast and adjust their focus quickly.

Like every other muscle group in the body, our eyes have a few main movement patterns which work in opposite relation to each other to stabilize the joint—or in this case, the eye. The main body movements are flexion and extension, internal rotation and external rotation, and protraction and retraction.

The eyes are the same. I’m not comfortable using the correct optometrist terms, so I’ll stick with the common terms of up and down, left and right, all the angles in between these, slight rotation to or away from the nose, convergence (cross-eyed) and divergence (bug-eyed). All of these movements come into play one way or another when the eyes focus on a target.

As your eyeballs move to see the target best, the colored part of the eye relaxes or contracts to change the amount of light that ultimately transmits to the back of the eye to the retina and then your brain “sees” what you’re focusing on. This description is an overly simplistic—yet accurate—portrayal of how our eyes focus, and it does have something in common with every other movement pattern the body produces: muscles make everything happen in sequence.

Since there are muscles involved in producing these movements, you can train the muscles surrounding and inside the eyes to become more efficient and faster in their movements, just like we do to help people run or jump. Here’s how I do it.

Eye Charts

I start with the most basic skill and have the athletes match letters and numbers from two sets of charts. One is smaller (4″x6″) held in their hand while the other is larger (8.5″x11″) and posted about 6-8 feet away from the athlete. Their job is to read their handheld card like a book (left to right and top to bottom) and then find the matching character on the far sheet as fast as they can.

When doing this sort of vision work, the athlete’s goal is to move their eyes as much as possible while specifically focusing on a target. We’ve had people do this while running their feet, doing some jumps, up-downs, or even switching cards during the set.

Another progression is to have them move the card or their body in different positions. To their right or left. Over their head or at their hips. Feel free to change the font size and colors to make it a bigger challenge. You can even do this with one eye closed. Let your imagination be your guide in how you want to challenge the athletes and overload the eye musculature.

Hand-Eye

Once people start getting good with the vision charts, the next step is to help them track an object as it moves in space. This is not something overly complicated. All I’m talking about is playing catch. Well, there is a twist—you need two different colored balls. In the video below, there are red and white lacrosse balls. Tell the athlete which hand is going to catch which colored ball. In the video, the athlete is supposed to catch the white ball in the right hand and the red ball in the left.

Video 5. The hand-eye catch exercise helps athletes track an object as it moves in space.

We start fairly easy, only going one ball at a time. Then, once the athlete has their rhythm, they turn 90 degrees toward me with their left shoulder pointing at me, but they still need to catch the ball with the correct hand. Lastly, the athlete turns 90 degrees the other way, so their right shoulder is pointed at me. This is a relatively easy progression.

Next, I throw both balls at once with high-low, both sides, and even a crossed-arm catching pattern. As with the vision charts, we do this with one eye closed or start with both eyes closed and opening on a “go!” call. These drills are to help the eyes focus on targets, not to help the person’s catching skills. Some people have never practiced catching drills before and will be discouraged quickly if you emphasize the catch. You should coach them up on their ability to see and react to the different balls.

Convergence-Divergence

The last vision skill we teach is done with some high-tech equipment: a six-foot piece of string or rope, five ½ nuts, a one-inch washer, and a dedicated carabiner. To set this up, tie off the washer to one end of the string, loop the nuts through the string (so they don’t slide off) every foot or so, and then tie the other end of the string to the carabiner, which you secure to your rack. When the athlete is ready, they hold the washer on the top of their nose right between their eyes then step back until the string is straight.

Their goal is to either converge or diverge their eyes so they experience a blurry double-vision of the string crossing at the first nut. Once that happens, they relax their eyes to come back to normal and then converge or diverge their eyes at the next nut, working up the string. This is harder than you’d think, and if they’re worried about always looking awkward while doing this drill—well, they’re right about that, but no one is going to notice.

Make a Difference Where and When You Can

The overall idea behind these drills is to fill the athletes’ time with quality work and not just to keep them busy. Pre-hab, grip, and vision work are areas that I’ve been quick to overlook in the past but are vital to an athlete’s overall development. Like you, I’m naturally drawn to watching someone set their new squat max, or shave a tenth of a second off their ten-yard sprint time because it’s fun to watch and is something you can feel proud about being part of. Seeing someone set a new PR on their string target convergence drill is not something I’m going to ever post on social media or brag out to other coaches because it’s not that glamorous.

On the other hand, if you’re like me and believe you’ll get the greatest improvements in performance by attacking people’s deficiencies, then maybe you should celebrate these improvements. Say you already have a basketball player who is strong (a double bodyweight back squat), fast (a 1.6-second ten-yard sprint), and powerful (30-inch vertical jump). What more can you really do with this person that’s going to impact their performance?

If I was working with a person like that, I might simply try to keep them healthy, fast, and strong. But that doesn’t improve their performance on the court. Would helping their eyes move and focus faster on what’s happening on the court change their performance? What about making sure their hands are strong enough to hold onto the ball coming down from a rebound? Save your answers, these are rhetorical questions.

Seeing people improve and stay healthy are always my goals for athletes. Just because the improvements happen in a non-traditional exercise doesn’t change the fact they’re still getting better, and their training is making an impact when they compete.

Since you’re here…

…we have a small favor to ask. More people are reading SimpliFaster than ever, and each week we bring you compelling content from coaches, sport scientists, and physiotherapists who are devoted to building better athletes. Please take a moment to share the articles on social media, engage the authors with questions and comments below, and link to articles when appropriate if you have a blog or participate on forums of related topics. — SF

[mashshare]

References

1. Zouita, S. et al. “Strength Training Reduces Injury Rate In Elite Young Soccer Players During One Season.” Journal of Strength and Conditioning Research, 2016; 30(5): 1295-1307.

2. Hewitt, T. E., et al. “The Effect of Neuromuscular Training on the Incidence of Knee Injury in Female Athletes: A Prospective Study.” American Journal of Sports Medicine, 1999; 27(6): 699-706.

3. Alentorn-Geli, E., et al. “Prevention of Non-Contact Anterior Cruciate Ligament Injuries in Soccer Players Part 1: Mechanisms of Injury and Underlying Risk Factors.” Knee Surgery, Sports Traumatology, Arthroscopy, 2009; 17(7): 705-729.

Leave the first comment

You must be logged in to post a comment.