Currently in his 26th year of professional coaching, Stuart McMillan is CEO and Short Sprints Coach at ALTIS. Stuart has worked with professional and amateur athletes in a variety of sports with a focus on power and speed development, and he has personally coached move than 70 Olympians at nine Olympic Games, winning over 30 Olympic medals. He has worked as part of national governing bodies in six countries and has been part of and/or led integrated support teams in the United States, Canada, and the UK. Stuart has also accrued the unique experience of coaching at three home Olympic Games, working with American athletes in 2002 at the Salt Lake City Games, Canadians in 2010 at Vancouver-Whistler, and British athletes in 2012 at the London Olympics. Most recently, he coached British sprinter Jodie Williams to a sixth-place finish in the 400m at the Tokyo Olympic Games.

Freelap USA: All the years of groundwork that go into building a successful high-performance business can also lead to a sense of “stuckness” for coaches who may want a change of geography but can’t imagine starting over—what were the moments that crystalized for you and your partners that moving ALTIS from Phoenix to Atlanta was the right course of action and a doable thing? And what have been the most unanticipated challenges you’ve had to overcome during this process?

Stuart McMillan: First, none of us really see this as starting over—as so much of our business is remote or virtual anyway, and the pandemic had reduced our on-site athlete population to a point where it didn’t significantly affect the athletes as a whole. Of course, not all the athletes made the move to Atlanta with us, but as a company, we just felt that this was a move we had to make for the best of the group.

We had an amazing time in Phoenix and met some wonderful people. Our partnership with EXOS over the last eight years is a big reason why we have been able to grow ALTIS to where it is today. I can’t thank Mark Verstegen and his team enough—and I will forever be indebted to them.

The motivation for the move was the fact that we didn’t feel like we were able to continue growing in Phoenix. To be honest, the last couple of years just felt a little stale for all of us. Of course, I’m sure the pandemic had a lot to do with that.

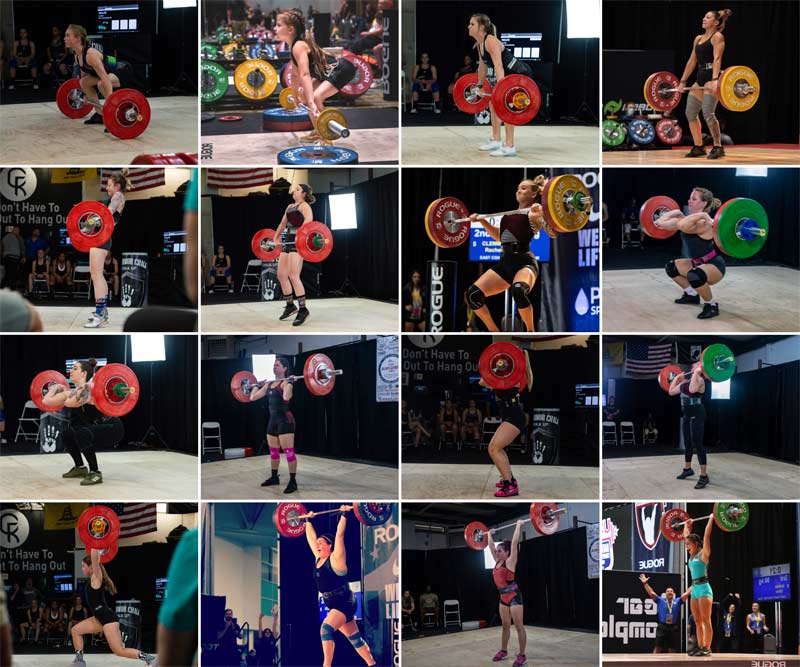

(Lead image and all photos courtesy of Lynwood Robinson).

As we have just arrived in Atlanta, the challenges are no doubt yet to come—but we look forward to meeting them head on. It’s only through challenge that we can grow.

One thing you learn with experience is that every five-year plan has a shelf-life of about a year or so before you have to revise it, so while we have some idea of the types of things we want to do going forward, we know that we will need to continue to be agile.

One thing you learn with experience is that every five-year plan has a shelf-life of about a year or so before you have to revise it, says @StuartMcMillan1. Share on XIn the short term, we hope to establish a number of great partnerships with local businesses here, and of course, we hope to welcome visiting coaches again in the new year.

As for knowing whether it is the right course of action—only time will tell!

Freelap USA: What inspired the specific Women in Coaching mentorship program at ALTIS and how do you hope to help impact the ongoing need to support greater numbers, improved retention, and better opportunities for advancement among female coaches?

Stuart McMillan: Much of the motivation in starting this initiative stemmed from the under-representation of women at our monthly Apprentice Coach Programs—especially female track and field coaches. (Most of the women who come through are S&C coaches, where it seems women are making inroads far more quickly than they are in track and field coaching.)

There are some significant challenges—most of which we are not expert in, and many of which don’t have easy solutions.

Where we sit on “quota systems,” for example, is something we need to think more deeply on—and seek further guidance on. My current intuitions echo those of my friend Rachel Balkovec, who said: “Quotas for hiring women are a bandaid for a deeper issue. We need young women to be interested in careers in sports, which is a separate issue from hiring women. Right now, due to low numbers of female applicants, it becomes difficult for an employer to select a qualified woman as their employee. The foundational issue is that while we have many women playing in high levels of sports, few of them choose sports as a career. Let’s start there.”

So how do we get young women interested in careers in sports?

Well, that’s complex—and much of it we can’t do a lot about.

But what we can do is provide better opportunities for female coaches to educate themselves. From conversations with many of the female coaches in our network and with some of the women who have attended our programs, it became clear that they are often not comfortable in a male-dominated, traditional educational setting.

How do we get young women interested in careers in sports? Well, that’s complex…but what we can do is provide better opportunities for female coaches to educate themselves, says @StuartMcMillan1. Share on XThis was the genesis of our Women in Coaching Initiative—which has spawned a very successful women’s-only ACP and a women’s-only mentorship program, led by ALTIS Head Coach Dan Pfaff and Education Director Ellie Kormis.

The response thus far has been amazing, and with the support of our community, we hope to expand the initiative further in the months and years to come.

Freelap USA: If you were a team sport coach in a high-level attacking sport and were shadowing you (or another ALTIS coach) through several weeks of training with a group of elite sprinters, what would be a few cues, drills, movements, or other training elements that you would observe and say yes, I’m totally stealing that to use with my athletes and what are a few elements you would see and say wow, that’s phenomenal, I’d be tempted to take that too… but I don’t think this will translate beyond the track?

Stuart McMillan: First, we are visited by coaches from other sports all the time. In fact, this was the genesis of our Apprentice Coach Program—to put some structure to coaches’ visits and to make it easier for us to provide a better experience for them.

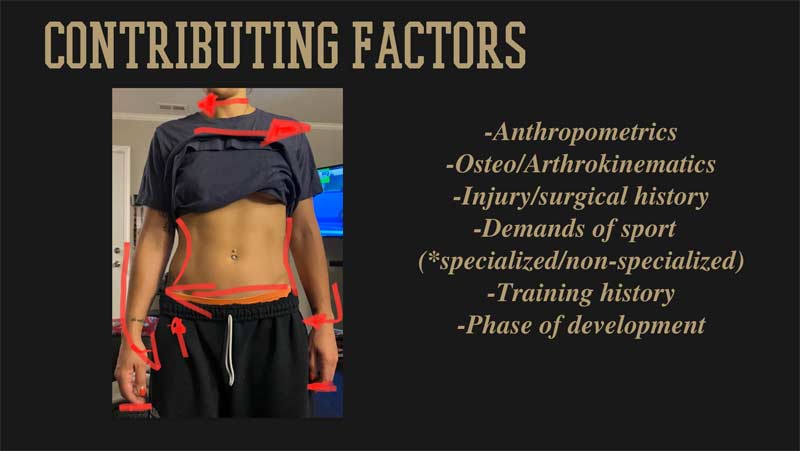

We actually discuss this very question at our initial meeting with the visiting coaches during the program. In essence, we warn them against simple “copy and paste” methods. The work we do at ALTIS is a product of the experiences of our coaches, our cumulative experience with athletes for decades, and our methodologies in the sport of track and field, at the elite end. And so, coaches with different experiences, who coach through different lenses and who work with different populations, must take all of this into account when observing our training.

I feel the industry as a whole has made the mistake of blindly copying from each other for far too long, and this has only been exacerbated in the social media era.

Rather, we encourage everyone to watch what we do, and ask questions about why we do it. Then, with that context, they should decide whether or not they can apply something similar to their own environments. Or even better, some may challenge us on our thought processes or the practical manifestations of these thought processes. Our senior staff have been coaching for a long time, but we all feel we still have a lot to learn, and I honestly feel we learn as much from visiting coaches as they do from us.

I feel the industry as a whole has made the mistake of blindly copying from each other for far too long, and this has only been exacerbated in the social media era, says @StuartMcMillan1. Share on XThat said, some things are common across populations—like the importance we place on how athletes move.

One critique I have of many coaches—especially in team sports—is their lack of attention to anything that happens outside of the weight room. Many coaches are sticklers for mechanics in the weight room but pay little attention on the field or court—instead, simply relying on a variety of “drills” to do the technical work for them.

The other thing we are known for is the emphasis we put on qualitative analysis. We do have some of the latest and greatest tech, but we are careful that we do not rely on it. In more than 30 years of coaching, I have yet to make a single coaching decision based only upon what a piece of technology tells me. I fear that this skill (and it is a skill) is a bit of a dying art. Too many coaches and sport scientists are overly reliant on numbers these days—and the quality of coaching has probably declined as a result.

So, to answer your question, probably the biggest thing I hope coaches “steal” from us is the importance we place on how athletes move, and our roles in influencing it—whether that be through explicit coaching instruction, cueing, constraints, improving various abilities and capacities, or therapy.

Freelap USA: Among the many takeaways from the Tokyo Olympics, the quality of “peacefulness” you’ve discussed in the past was a defining quality of several medal-winning sprint performances. How do you define and emphasize this quality with ALTIS athletes and what are some hands-on ways you coach and cue the state of freedom or peace in a sprint race?

Stuart McMillan: I’ve often said to visiting coaches who ask me about coaching instruction and cueing that “my goal each day is to say nothing.” I have never quite succeeded at this, but through using this mantra as a goal, I am continually reminded that the words I use matter, and so I should be careful with my choices.

One way I try to reduce the number of words I use is through the use of what are called mood words—words that, when said or thought with the appropriate feeling and/or emphasis, may positively affect movement outcome.

Performing artists, for example, often express a particular mood by dramatizing a single word. The right word at the right time will cause a physical reaction in the body and improve performance.

A sporting example is a rower who repeats to herself the word “BOOM” during the catch of each stroke, as a way of increasing the initial force of the pull of the oar through the water.

The right word seems to bypass the need for more complicated explanations. The technical instructions just seem like they come along for the ride.

As it pertains to “freedom” and “peace” with sprinters (and this is actually the case with athletes in many other sports as well), the most successful are often those who do the best job of “staying relaxed” under high levels of arousal. They balance the requisite ferocity of speed-power sports with the freedom needed to move efficiently.

The problem is asking an athlete to “stay relaxed” is easier said than done—especially in competition—and in many cases this can have a deleterious effect on their force-producing abilities.

I find that the words “freedom” and “peace”—at least for many of the sprinters I have coached—have the effect I want on the relaxation but without the decrease in power.

Mood words are one way I attempt to influence performance, but it’s not the only way. There are many times I have longer conversations about mechanics that a few words don’t sufficiently cover.

Finally, I have two words of advice when it comes to using mood words:

- Like all coaching instructions, mood words are contextual. They depend upon your own experiences, the experiences of the athlete(s) you are working with, their sport, their technical objectives, etc.

- While mood words have been shown to improve performance, that is very different from improving learning. Coaches would do well to understand this difference in depth.

Freelap USA: You’ve talked about preferring to home in on and accentuate an athlete’s strengths and being wary of focusing too much on targeting weaknesses lest those efforts in some way compromise the unique abilities that are the athlete’s gift in the first place. If, however, a weakness you identify is on the mental side, when and how do you go about trying to further develop that psychological component to lift that quality to balance out with the level of their physical, technical, and tactical abilities?

Stuart McMillan: I feel that the “mental side” of sport continues to be most challenging to most coaches of elite athletes.

As to your question—we first need to understand what we mean by “mental weakness.” One of my pet peeves is coaches who blame performance on an athlete, using such terms and phrases as “head case,” “mentally weak,” “choker,” etc.

Often, it’s just coaches passing the buck.

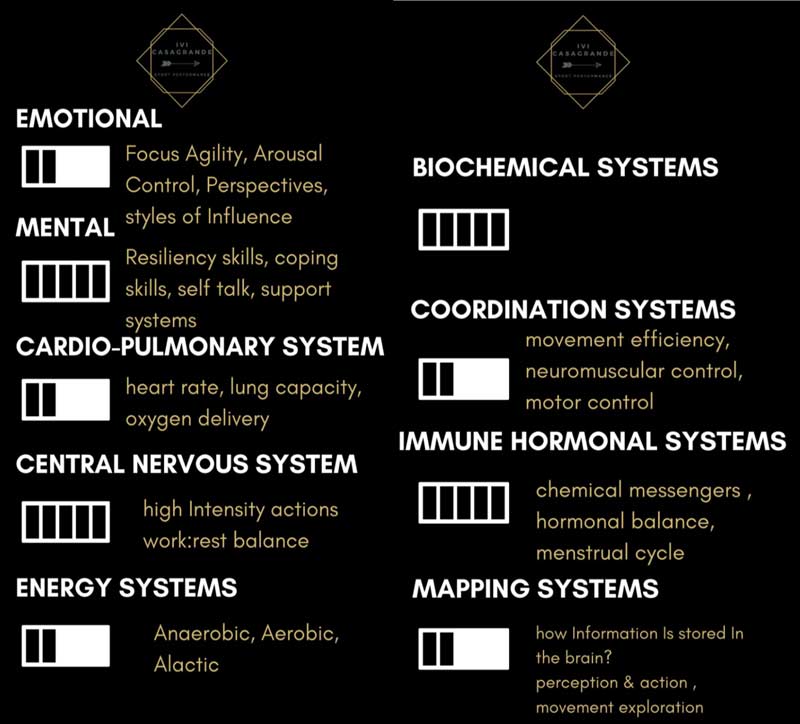

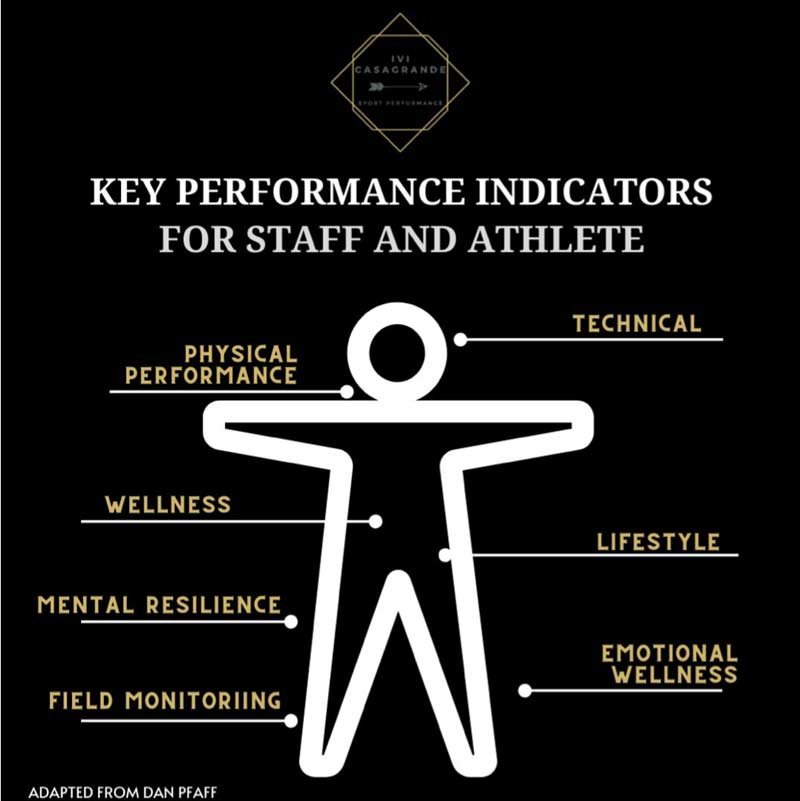

The best coaches are the ones who understand how all the many systems of the body interact with each other. They appreciate that coaching is the ultimate generalist profession.

The best coaches understand how all the many systems of the body interact with each other. They appreciate that coaching is the ultimate generalist profession, says @StuartMcMillan1. Share on XThis means we have to know quite a lot about quite a lot.

Sometimes, we can be blinded to the totality of the sport performance system by the specific lens through which we look at performance: the classic “if all we have is a hammer, everything looks like a nail.”

And sometimes, rather than stretching out and learning things we don’t know, we stick to what we are comfortable with.

Because the “mental side” of sport is so challenging, many coaches just throw their hands in the air and give up. But the mental side is the essence of coaching.

(All photos courtesy of Lynwood Robinson).

Our jobs rely on the athletes we coach believing what we tell them, believing in the work we ask them to do, and believing in themselves. This is something that I don’t look at separately from other parts of the program, but instead concurrently.

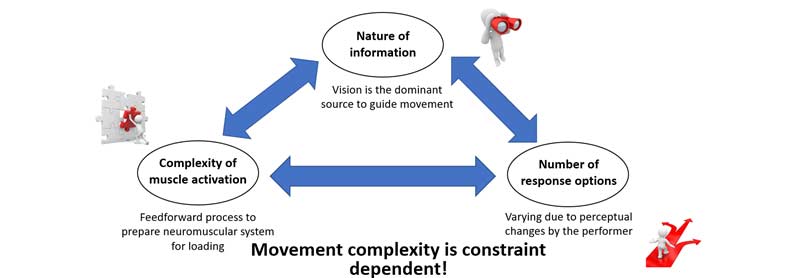

The stability of a motor skill is arousal-dependent: meaning, just because an athlete has stabilized a skill at a low level of arousal doesn’t mean it is stable at higher levels. Coaches often confuse technique with skill and underestimate the effect that arousal has on skill. A technique is the application of the sport-specific ability without context, while a skill is the application of the sport-specific technique in context.

For example, while a solo block start in training might require the same technique as a block start in a competition, they are not the same skill—as they have very different contexts and very different amounts of information.

As information increases, complexity rises, and the level of arousal increases.

So, if an athlete can do a great block start by themselves in training, and they don’t when it comes to race time, I understand the desire to term this “choking”…but that’s overly simplified—and actually inaccurate.

Part of our job as coaches is to ensure we prescribe training that appropriately stresses the level of expertise that an athlete currently has. Progression comes from setting up challenges that are just outside of an athlete’s comfort zone and then helping them to rise to them and overcome them.

My friends Brad Stulberg and Steve Magness put it perfectly: stress + rest = growth.

In their book Peak Performance, they write about the “grey zone,” where we either don’t rest well enough or don’t stress ourselves enough. If the stress is too high (or the rest too small), then the athlete won’t be able to meet the challenge. If the stress is too low (or the rest is too great), then there is no challenge at all—and no growth.

I think if coaches begin to take a more holistic approach to coaching—where they treat all systems not as independent of each other but as interacting parts that are interdependent on each other—they will begin to see that “mental weakness” doesn’t exist in and of itself. Instead, it is a matter of prescribing the right amount of work at the right time: just like all training.

In my own program, I work toward an athlete’s comfort. I organize my training to try to take advantage of an athlete’s strengths—spending more time on what an athlete struggles with earlier in the training season compared to what they are better at later on.

During the pre-competitive and competitive parts of the season, I want the athlete to feel good—confident and comfortable in their abilities—so I don’t push the boundaries with the challenges; if they’re not ready, they’re not ready.

We will take our licks and live to fight another day.

Since you’re here…

…we have a small favor to ask. More people are reading SimpliFaster than ever, and each week we bring you compelling content from coaches, sport scientists, and physiotherapists who are devoted to building better athletes. Please take a moment to share the articles on social media, engage the authors with questions and comments below, and link to articles when appropriate if you have a blog or participate on forums of related topics. — SF