Training for speed should be a non-negotiable for any team sport athlete. There are big mistakes still being made in training for speed, however. Once they’re corrected, it can springboard your athlete’s development.

1. Training Speed After Lifting

The biggest mistake I continually see in training is trying to do speed work following lifting. There are four primary reasons that this becomes a problem.

1. Athletes need near maximal speeds to develop that quality.

-

- To raise the ceiling of maximal velocity, speed training requires the body to be fresh from fatigue.

Why?

-

- Developing speed is highly intensive and demanding on the nervous system. The faster the athlete, in fact, the more demanding it is. Lifting creates fatigue—impulses sent through the nervous system between the brain and muscular system don’t move as fast when fatigue is present.

Lifting not only fatigues the CNS but also creates damage to the muscle fiber itself. Tired and damaged muscles don’t have the ability to contract and relax at the speeds necessary to develop the quality of maximal speed. Valuable training time and energy are spent trying to run fast without being able to do it.

2. Heavy lifting beforehand creates a tension-filled training session.

- We’ve all left the weight room with that tight, blood-filled, muscled-up feeling. Top end speed relies on the ability to stay relaxed. Reactivity is a key ability in elite-level sprinters. It is the ability of the muscle to cycle through contraction and relaxation. That happens faster when athletes are relaxed in motion, not when they are tight and tense following a heavy weight session.

3. The risk of hamstring injuries following a fatiguing lifting session rises exponentially.

- It doesn’t take a genius to understand the risk to the hammies after you’ve done heavy sets of five on the RDL before sprinting. The faster the athlete, the greater the risk. They don’t take thoroughbreds off the plow just prior to running in the Derby.

4. Field work such as sprinting should be the priority with all team sport athletes because that truly is their sport…sprinting on a court or field.

- They don’t lift a barbell or bench press on the field/court. Lifting should always be supplemental to the movement patterns and speeds that are in the game.

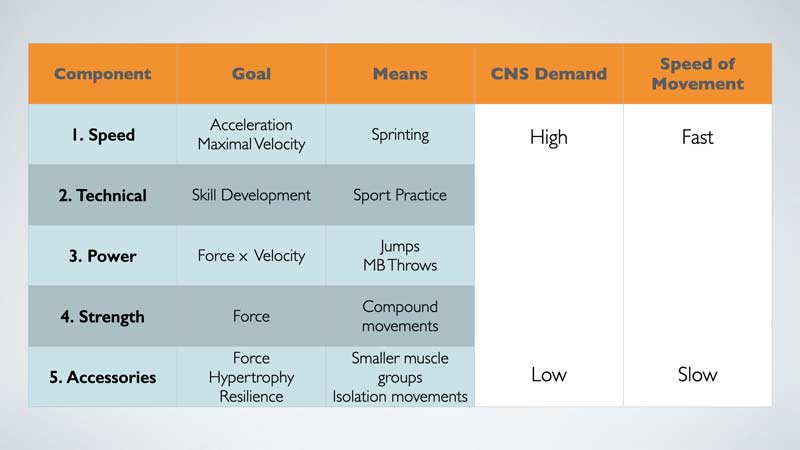

CNS fatigue from highest to lowest should dictate the order of training. To maximize training, movements that happen at high speeds should be early in the training sessions when athletes are freshest. The order that we use is as follows:

2. Not Giving Enough Rest Between Reps

To get the desired training effect of speed development, rest intervals become critical. Too little rest between sprints and fatigue begins to accumulate, causing quality to diminish. When it comes to speed training, QUALITY is the most important aspect. Coaches often see the low volumes and long rest periods as not hard enough and eliminate proper rests.

There are many ways we can fill the rest intervals to have the appearance of being busy. Joey Guarascio has a great article on SimpliFaster detailing his approach to team speed training. Waterfall starts are an idea he discusses that we have used for many years. These not only allow us to view each athlete’s rep individually, but they take up more time as well. That extra time adds up to longer rests and higher-quality work.

A great benefit that rarely gets talked about is each athlete gets to watch their teammate’s previous rep. We all know that teaching is best done through watching, listening, and doing. Watching the previous athletes perform the movement and get coached adds another level of development for each person waiting in line.

A second method we’ve utilized to enhance rest times is super setting non-competing work like medball throws and/or jumps. Our athletes perform their sprint, then walk to another area of the field and perform a few reps of a medball throw variation or jump variation. The long walks between stations add to recovery time, while adding in throws/jumps allows us to attack another issue.

Developing speed is not meant to be extremely fatiguing on the muscular and cardiovascular systems. Athletes should not be tired when training to get fast, says @ZachDechant. Share on XDeveloping speed is not meant to be extremely fatiguing on the muscular and cardiovascular systems. Athletes should not be tired when training to get fast. Mental toughness does not apply during speed training, although many coaches make the mistake of cutting rest times because it’s “too easy.”

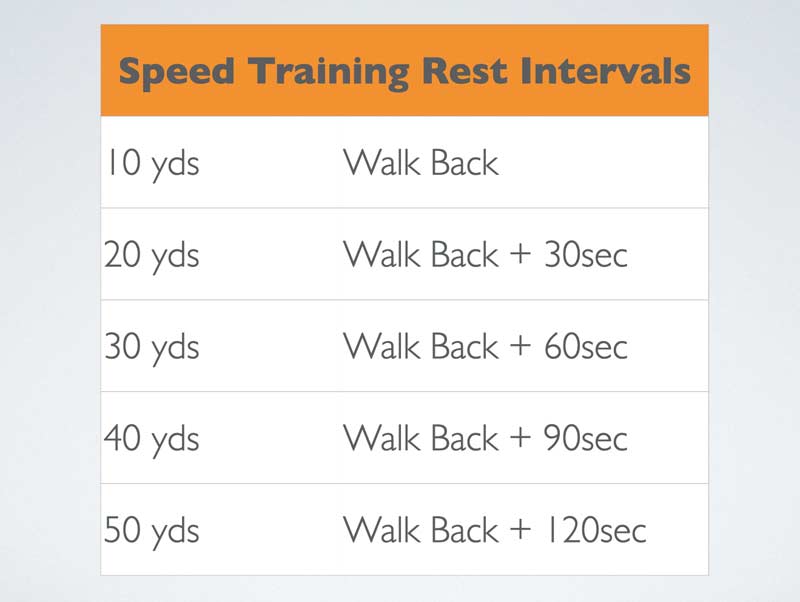

The ideal guidelines that we have traditionally tried to follow are one minute per 10 yards of distance. A 40-yard sprint requires four minutes of rest prior to another sprint.

This becomes incredibly difficult within the time parameters that team sports must currently follow at the collegiate and high school levels. In essence, we have modified those original parameters to fit our needs. The modified rest parameters that we currently use include a leisurely walk back to the start along with a short rest when there.

Shorter distances from 5-20 yards aren’t as demanding on the nervous system as longer full-speed sprints, so we have more freedom in rest periods. The key is to make sure athletes have not only caught their breath but feel restored before the next rep begins. The ultimate goal is speed development, not just running, so restoration means attaining the highest possible velocity in the next rep. When it comes to speed and acceleration development, quality over quantity always.

3. Not Consolidating Like Stressors

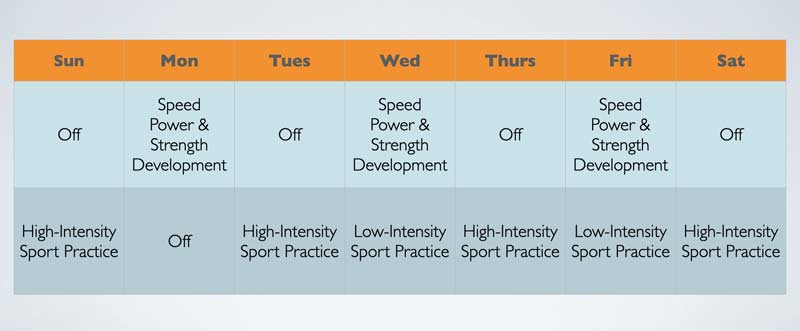

On the topic of rest and recovery comes consolidating stressors during the week. The best way to ensure recovery for training sessions is to organize training and practices properly. That means organizing high-intensity elements together and low-intensity elements together.

All too often, the silos of sports performance override this. The weight room is programmed separately from sport practices, with each coach having their own agenda. When we don’t have high-output days surrounded by either rest or low-intensity days throughout the week, fatigue accumulates. When fatigue accumulates, intensity/maximal outputs suffer, injury risk goes up, and performance gains cease to exist. For ultimate athlete health and performance, all areas need to be aligned holistically.

This applies not only in the weight room, but in sport practice as well. Not adhering to this model between ALL training comes at a cost. If sport practices and training don’t consolidate stress, athletes rarely get a chance to recover. Between sport practices and training, it’s not unusual for athletes to experience high-intensity sessions every day when we don’t adhere to a holistic model.

It’s not uncommon to see the above example on a weekly basis for team sport athletes. Coaches believe that to get better, they must attack each element with high intensity on alternating days. The thought process of why can’t we train with high intensity when we have a high-intensity practice day exists. The inherent problem that this creates is when do the athletes have a chance to recover? This is why sport/skill coaches and performance staff must all be on the same page with the weekly plan. Consolidating ALL stressors throughout the week is a must for recovery.

We must keep in mind that athletes do not just experience stress in sport. Stress is holistic for all aspects of life, and we must program accordingly, says @ZachDechant. Share on XWe must keep in mind that athletes do not just experience stress in sport. Stress is holistic for all aspects of life, and we must program accordingly.

4. Believing Submaximal Training Has No Role

Athletes don’t break PRs every single time they train. The intent may be maximal but realized intensity as a percentage of their absolute best may fall just short. By nature, if they aren’t breaking PRs, then their training is submaximal.

Regardless of semantics, that’s not the submaximal I’m referencing in this instance. We’re talking about one click underneath maximal intent. I would classify most maximal intent sprints at 96%+ and submaximal speed work in the 88%–95% range. Many people think submaximal sprint training is a waste of time. Earlier in my career, I would have agreed. However, thanks to ALTIS and Stu McMillan, I’ve come to realize there are benefits to submaximal speed training.

Sprinting—and especially maximal velocity sprinting—is a skill. As such, that skill often needs to be refined and/or altered. Any skill is difficult to change or refine when performing it at absolute intensity.

Certain drills can play a role in decreasing maximal intensity and helping to build technical proficiency, including:

- Wickets.

- PVC runs.

- MB runs.

- Technical buildups.

These drills are generally performed at submaximal velocities, either because of the constraints of the drill or purposely at lower intensities to allow for skill enhancement.

For real-world evidence, look no further than a recent study done by Jurdan Mendiguchia: “Can We Modify Maximal Speed Running Posture? Implications for Performance and Hamstring Injury Management.” The study aimed to examine whether a specific, six-week intervention of combining lumbopelvic control and running technique exercises could induce changes in pelvic kinematics at maximal speed and improve sprint performance.

The results of the study speak for themselves. Not only did the researchers have success showing that they could refine and improve maximal velocity mechanics, but they also had significant decreases in time, resulting in improved performance.

The way in which they achieved their results is what we’re after here. In the technical warm-up for a training day, the study used traditional drills that many coaches use on a regular basis with their athletes. These included variations of the A-series and dribbles. The main portion of the sprint training, derived at maximal outputs, included many drills and again dribble variations. These drills give credence to the fact that submaximal speed training can be very useful for speed gains.

Creating Adaptations

Following a few key principles with speed development will create a better chance for your athletes to create specific adaptations:

- Order training from fastest to slowest.

- Quality is the most important variable, which means optimal rest times in training sessions.

- Consolidate stressors (both on and off the field).

- Use the range of opportunities to develop speed submaximally.

Lead photo by Juan DeLeon /Icon Sportswire.

Since you’re here…

…we have a small favor to ask. More people are reading SimpliFaster than ever, and each week we bring you compelling content from coaches, sport scientists, and physiotherapists who are devoted to building better athletes. Please take a moment to share the articles on social media, engage the authors with questions and comments below, and link to articles when appropriate if you have a blog or participate on forums of related topics. — SF

References

Dechant, Zach. Movement over Maxes: Developing the Foundation for Baseball Performance. 2018.

Mendiguchia J, Castaño A, and Jimenez-Reyes P, et al. “Can we modify maximal speed running posture? Implications for performance and hamstring injuries management.” International Journal of Sports Physiology and Performance. July 2021. doi:10.1123/ijspp.2021-0107