Sport can cause swings in emotion, varying from passion to disappointment. It can produce an emotional environment that, at times, causes us to wobble and lose our composure. However, that same environment can also cause us to proactively respond and find new levels of competitiveness that raise our game.

The psychology of sport is certainly not a cliché element. It can be, and often is, claimed as a romantic and comfortable part of something that we have all probably participated in: competition. The role of this article is to break away from the clichés and offer well-founded information that is currently being used with young athletes who have the ambition of pursuing excellence.

If we are not quite ‘mentally switched on,’ our physical qualities will probably also decline, says @JamyClamp. Share on XThere is an undeniable link between our attitude, our approach, and the effort that we exert towards a task and its overall outcome. In essence, if we offer a positive attitude and direct our energy towards the desired outcome, then, ultimately, there is a greater chance of eliciting conducive thoughts, feelings, and, importantly, behaviors.1 So, cognitively, if we are not quite “mentally switched on,” our physical qualities will probably also decline.

Work Ethic and Accountability

There is an increasing number of young people that, as Kelvin Giles says, “want it now and want it easy.” It is definitely not all doom and gloom, however, because there is a very large number of people out there that will commit with 100% intent, acknowledge their mistakes, and seek options to make things better, remain close to their values, and tell you what they think. If you work with someone like that, look after them because they are a real gem.

As strength coaches, we like to see PBs in the weight room, but I personally enjoy nothing more than working with somebody who brings character, intensity, and effort to the floor. They can serve as a role model and raise the ceiling for everyone in the environment. As coaches, we must project the characteristics that we seek. So, if we have identified honesty as a key quality in our environment, we should also be bold enough to “fess up” and say what needs to be said, as opposed to saying what people would like to hear.

Honesty is not just something that we use when we make a mistake; it is doing what is best for an individual at any time. We are role models to those that we coach. Nobody will benefit from hypocrisy—if we say we value something and we agree on it, that is that.

I attended one of Mark Bennett’s Performance Development Systems workshops and he stresses the importance of “non-negotiables.” These are the elements that we agree on with our athletes, and then are relentless and patient in pursuit of them. We need to demonstrate them in everything that we do.

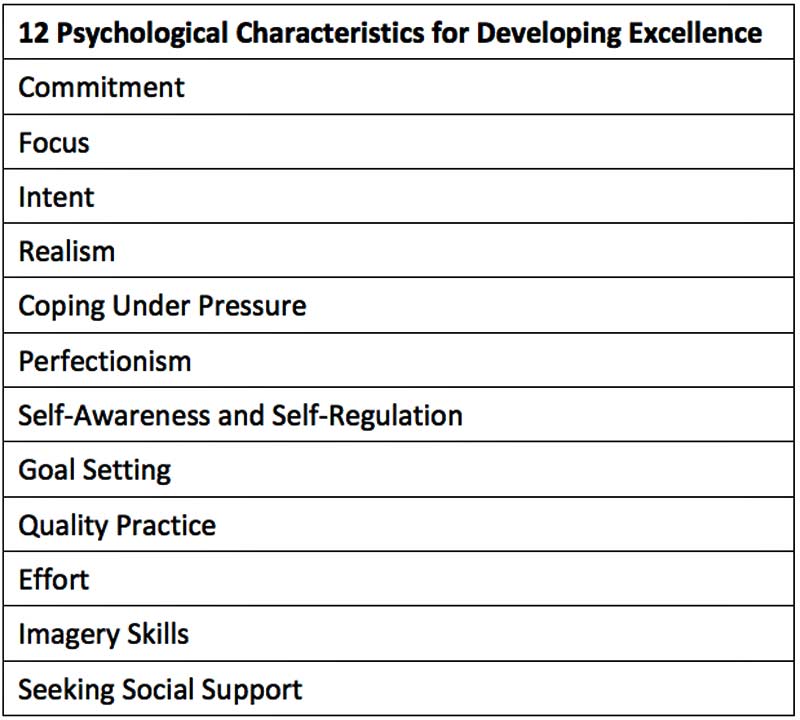

12 Psychological Characteristics of Developing Excellence

Areas that are commonly discussed within sports psychology include confidence, attitude, “culture,” motivation, frustration, focus, and arousal. All play their part in performance, but there are definitely more psychological skills that coaches need to foster in order for an athlete to sustain their performances over a prolonged period of time. In the literature, these traits are referred to as “psychological characteristics of developing excellence (PCDEs).” 2 As the term suggests, they include many psychological traits observed among individuals that have achieved relative success in their careers. Some will say, “If you’ve got them, great. If you don’t, good luck.” Let’s say that if they are present, there is a greater chance of a young person fulfilling their potential.

If a young person is ‘present,’ there is a greater chance of them fulfilling their potential, says @JamyClamp. Share on XAs is often the case, the path of performance sport, whatever that means for the particular individual, is rarely a linear and smooth route. The likelihood is that the athlete will encounter some bumps and, with help from their support network (including us as their coaches), they will need to work out how to either roll over a bump or navigate their way around it.

Before delving into the highlighted characteristics, it is important to recognize that, as coaches, we have a great opportunity to foster the desired skills and contribute towards the overall growth of the individual we work with. That being said, it is not only the coach that can influence psychological development. Parents, family, teammates, friends, and teachers all have a role to play, so it is worth involving them in the process.

Without support and understanding from those stakeholders, the progress that athletes make during training, and sometimes away from training, can be undone when they do not recognize the underlying reasons behind the changes in behavior. With this, always provide a “why” when introducing new concepts regardless of how “right” they are. It is not always as clear to the stakeholders who has the best possible intentions for their child or friend, including us as their coach.

Consider the young player that is eager to develop their nutritional habits but, when they suggest “better options” to their parents, they are brushed away. Thus, the usual—and sometimes poor—habits remain. This is a fundamental problem because I guarantee the young player will become frustrated and suffer the consequences of poor habits, and this will reduce their chance of realizing their potential. Involve their parents, clearly explain why nutrition is paramount, and suggest ways that it can be made more effective and—you guessed it—they might just warm to the idea. Even more than them warming to the idea, we need them to actualize it, so keep in touch and see how things are going.

Highlight what psychological characteristics look like as you would with technical models, says @JamyClamp. Share on XWe need to highlight what these psychological characteristics look like as we would with technical models, such as teaching the squat. It’s great shouting them from the rooftops, but unless people actually know what they mean, they are more or less useless.

Table 1. These 12 psychological characteristics for developing excellence significantly contribute towards the realization of performance. (Based on Talent Development: A Practitioners Guide.)3

1. Commitment

Without motivation, commitment will more than likely stumble. As you have probably gathered, many of the psychological characteristics are interdependent, meaning that without one, the others may suffer. Commitment is our direction, drive, resiliency, and energy towards our role. I recall coaches asking me; “Did you apply yourself to that?” If we have applied ourselves to the role, we will direct almost, but not all, of our energy towards it. “Pursue excellence because nothing else is worth your time” springs to mind.

Commitment and motivation are inextricably linked and, for this article, I will link it with Self-Determination Theory. Competence, autonomy, and relatedness are three of our basic psychosocial needs. When none of them are met, our motivation and commitment towards a task wane. That is a problem because, as with most things, there can be a “hurricane effect” whereby one issue grows and starts to pick up, and feed into, other issues. There are then those athletes driven by progressing and those fearful of regressing.

Progress generally motivates the people who can self-regulate their behavior, and their thoughts. One of the best ways to develop commitment is to create an emotional attachment and an understanding of what is happening and, importantly, why it is happening. If the athlete is invested in the goal, they will not want to let their team down and they will do what is necessary to maintain progress.

2. Focus

Maintaining focus when distractions inevitably occur is an important skill. Without it, not an awful lot will happen. The ability to regain focus is maybe even more practical. Unless you are a robot, I would suggest that you have momentarily lost your focus at one time or another. It is important how we respond and regain composure and, with that, focus. Sport obviously requires a variety of skills, so there is a danger that athletes start to direct “too much” energy, both physical and cognitive, towards a particular element. As a result, they are more likely to lose sight of their goal.

As Mike Young told us as a group of interns in 2016, “The goal’s the goal.” To elicit focus, I personally like to ask the athlete what the goal is: “Remind me what you are working towards?” If the behavior is not conducive to the goal, then why is it occurring?

3. Intent

Determination, drive, and application all come to mind. Approaching our work with an intent to produce our best possible output should be the goal, but to do that, we have to care about what we do. If we have little interest in the work that we do, we are unlikely to work with the desired intensity, unless the value is highlighted. For example, why are we doing heavy squats today? What is the benefit of doing this? Answer that with clarity and, if your athletes are there to progress, they will lift with intent.

This particular psychological quality is very much linked with the PCDEs mentioned because there will be a good number of people that require a very small amount of additional motivation. Often, people will have their goals, as well as their drives, and they will direct all their energy towards that outcome. However, when it is not as straightforward, and intensity is lacking, we need to relate our approaches to the overall goal. Again, Mark Bennet refers to goals as “critical outcomes.” So, in essence, it is a matter of relating, and transferring, everything towards the critical outcome.

As a simple example, if somebody wants to improve their starting speed and we prescribe exercises with a dynamic effort emphasis, we need to clarify the reasons behind that approach. We can definitely develop intent because, ultimately, behavior will change over a period of time. Behavior is a dynamic concept and we largely serve as “choice architects.”

4. Realism

“Everyone has a plan until they get punched in the face.” We need to accept that somewhere along the way, our plan will probably let us down. However, if we understand that and don’t become too rigid and structured, we are more than capable of reacting. It becomes an issue if we plan and are completely oblivious to potential roadblocks because, if and when it all falls apart, it might take a while to react and work things out. That concerns planning, or periodization, in the sense of “writing in pencil and being prepared to change.”

We need realism in our ambitions. While it is great to set lofty targets, if they are out of reach at that moment and we know that they are, it will hurt when we don’t achieve them. There is then the argument of “talent needing trauma” for us to learn how to respond to future setbacks and adapt. That concept, of course, has a place, but considering the effect of stress on our health and performance, is it sensible to expose ourselves to a chronic stress stimulus?

We need realism in our ambitions so we can see and react to potential roadblocks, says @JamyClamp. Share on XI think that a lot of goals are imposed on people, which raises the topic of perfectionism. As a coach, I tend to provide regular feedback at the end of the session to address what is going well and what needs improvement. If something is not quite good enough, then I will state it because it is of no real benefit to temporarily fill the cracks. Feedback is positive and objective in nature, wherever possible. By that, I mean that comments are not just positive buzzwords but, rather, they carry genuine meaning and are founded upon observations and measurements.

5. Coping Under Pressure

Excessive stress is not good for our health in general, let alone when we are attempting to perform and improve our standards. Similarly, on the idea of “chaos in training”—Is there not already enough chaos in “our” athletes’ lives, including school, work, personal relationships, and personal commitments? Are we throwing larger rocks at people who, unbeknownst to us, have already had a few thrown their way recently?

With that said, we need to take the time to engage with people without making it a fluffy questioning session. Investing your effort, energy, and interest, and giving positive-objective feedback, far outweighs the often “tea party”-like approaches to psychology. It is not appropriate to shelter someone from stress because, the reality is, it will probably show up at some point and challenge our ability. Instead, we need to help develop coping mechanisms that work for the individual as opposed to rolling out the book of standardized questions that work for everyone—they don’t.

Why Developing Coping Strategies Is Important

We must also consider the attitudinal effect on biochemical balance, particularly in and around dense training periods. John Kiely has really sharpened my approach to this area with his belief that imposing stress on the body is more than a physical stimulus. Instead, as an athlete executes a program, there are psycho-emotional and cognitive stressors occurring that influence our output. This is obviously not only applicable in sport.

If we are chronically stressed, anxious, and just generally a walking time-bomb, our performances will be quite poor. Sleep, for example, is often neglected, both by choice and by nature, due to chronic stress. With stress comes increased allostatic loading, or our body tries to restore internal balance, and then sleep quality declines.4 Why is this important? Well, if we ignore the reality that stress is a psychological concept and neglect the biochemical stress response, the athletes that we coach will more than likely have limited progress. More holistically, it will damage their overall condition both physically and mentally.

6. Perfectionism

Perfectionism is one of those traits usually associated with the devil and it has certainly been thrown on the coals. However, while the pitfalls of the quality are regularly highlighted, there are also plenty of positives. There are two forms of perfectionism: harmonious and obsessive. Harmonious perfectionism is driven by enjoyment, passion, and autonomy. Obsessive perfectionism is powered by, well, obsession and a feeling of guilt and failure if certain things are not done.

We certainly want perfectionistic traits because, with harmonious drives, there are evident benefits. However, if they become excessive, the damaging effects are also noticeable—primarily burnout, but also the lasting effect that these traits have on the individual, their family, and their friends. Whichever type of perfectionism we identify needs to be controlled, but certainly not caged.5

There are plenty of “perfectionism stories” in sport that are then glorified. However, it is often just people doing their jobs to the best of their ability and wanting it done well. Perfectionism is a difficult trait to control, so this is where regular conversations become paramount. If things are not going quite to plan, then you need to have a conversation about why this is the case and that it is okay, as long as you all work hard to get back on track.

7. Self-Awareness and Self-Regulation

Without self-awareness, we will struggle to understand what we are good at and what we are poor at. It is, therefore, no coincidence that some of the greatest athletes and coaches all tend to display high levels of self-awareness in their behaviors and performances. Self-criticism is, again, another trait that people view as a “dark side” quality. There are two sides to the coin, however, as excessive self-criticism can be damaging but there needs to be sufficient honesty to accept that things are not quite good enough. With that comes self-regulation: the process whereby people manage and change their own behaviors in accordance with their goal.6

In general, those with better self-regulation skills, such as evaluation, reflection, and planning, achieve more productive learning and performance outcomes. Athletes that self-regulate their behavior have a strong overriding purpose, and they understand their current levels and what they can progress towards.7 Active learning will always encourage self-regulation because it encourages high levels of accountability and autonomy, so while the coach acts as a facilitator, the athlete works things out for themselves. To me, this is the ultimate goal: Give the athlete the tools to then replicate their training without supervision.

8. Goal Setting

Goals must be created by the athlete. A goal that is imposed will not have the same meaning to the individual. In essence, it has to invoke a sense of passion and determination, so that when things do go wrong, there will be a work ethic in place that is capable of overcoming the obstacle.

By all means, follow the SMART principle, but you must also regularly monitor the goal. In addition, identify what the goal is and then work backwards. This is the principle of reverse engineering in process. To achieve the goal, we must know what is required to achieve it because, without the requisite components, we are probably training aimlessly.

9. Quality Practice

There is a substantial amount of literature surrounding the type of practice that we plan; however, that is beyond the scope of this article. By “quality practice,” I mean the attitude that coaches and athletes display in terms of commitment, intent, and effort. The coach assumes a pivotal role in developing quality practice sessions, but then the athlete must take ownership of their performance and approach everything with the desire to develop. Every session is an opportunity to develop.

In my experience, there have been many young athletes that display a genuine desire to learn how to train and develop their ability. They are exactly what we look for. Now, because we are social beings, there is a danger that if we highlight those individuals as the “shining lights,” other team members are going to grow to dislike them.

This is not what we want, but rather, a desire from every team member to represent the environment and help things move forwards. This is where an environment of excellence becomes prevalent again. Frank Dick talks about “the badge” and being passionate about the organization. I fully agree, because if you care about the “badge,” you will probably do the required work, and do it with high levels of intensity, commitment, and effort.

10. Imagery Skills

Having an idea of what success looks like is a valuable skill. Everyone has different ambitions and success looks extremely different for many of us. For some, it may be tangible (financial reward), but for others, it may be intangible (making family proud). Neither are “wrong” because, as always, the two rewards can intertwine.

With effective imagery skills, there is a greater chance of developing a confident performer. During practice, they envision the required intensity, and then they perform the repetitions. They can imagine themselves performing with clarity and, when the time comes to physically execute, they are often ready.

Knowing what success looks like and being able to visualize it is a valuable skill, says @JamyClamp. Share on XObviously, to truly prepare for competition, they need to experience a competitive atmosphere. There are many athletes that are excellent during practice, but on game day they do not fulfill their potential. As long as we do not simply throw them into the competition without any guidance, I am confident that they will be okay. Part of the issue is that athletes often do not have a coach with them, which is very important.

11. Effort

To progress at something, whether a skill, education, or our job, we must commit to it. If we are simply going through the motions on a regular basis, progress will be limited. It is about starting with a goal at the front of the mind, lighting the fire, and keeping it alive for as long as possible. Effort means taking a relentless, but very patient, path towards that goal.

12. Seeking Social Support

“Everyone needs a mentor and a couple of people around them that will give them a clear, unbiased view.”–Paul McGinley

This quote typifies what seeking social support is about. With that, I think we all have a responsibility to make sure that people are okay because, sometimes, they won’t be comfortable seeking support. We have to create a warm environment because we definitely do not want people on edge.

Everyone on the Same Path, Bringing Their Value

Being part of a team, naturally, requires working together to achieve the objective at hand. This is the Shared Mental Model concept: Everyone shares the desire to achieve the objective and an understanding of what is going to happen.8

I primarily work in private coaching, and this is particularly important because, at times, we are not there when “our athletes” train. So, whoever is available should be able to offer the necessary support and ensure that everything is done correctly. There will be more than one coach in contact with athletes, which is a good thing. However, if we want clarity, we need to all think in the same way, only with different approaches.

An athlete’s coaches should all think in the same way, although they have different approaches, says @JamyClamp. Share on XThere are many ways to get to Rome. Some may get us there quicker, but on the whole, most routes will get us there.

References

- Hays, K., Thomas, O. & Bawden, M. (2009). “The role of confidence in world-class sport performance.” Journal of Sports Sciences. 27 (11); 1185-1199.

- MacNamara, A., Button, A. & Collins, D. (2010). “The role of psychological characteristics in facilitating the pathway to elite performance. Part 1: Identifying mental skills and behaviours.” The Sport Psychologist. 24 (1) 52-73.

- Collins, D. & MacNamara, A. (2018). Talent Development: A Practitioners Guide. p.69. Routledge: Abingdon.

- McEwen, B. (2007). “Physiology and Neurobiology of Stress and Adaptation: Central Role of the Brain.” American Physiological Society. 87; 873-904.

- Hill, A., Macnamara, A. & Collins, D. (2015). “Psycho-behaviourally Based Features of Effective Talent Development in Rugby Union: A Coach’s Perspective.” The Sport Psychologist.

- Kirschenbaum, D. (1984). “Self-regulation and Sport: Nurturing and Emerging Symbiosis.” Journal of Sport Psychology. 6; 159-183.

- Toering, T., Elferink-Gemser, M., Jordet, G. & Visscher, C. (2009). “Self-regulation and performance level of elite and non-elite youth soccer players.” Journal of Sports Science. 27 (14); 1509-1517.

- Jonker, C., Riemsdijk, M. & Vermeulen, B. (2010). “Shared Mental Models: A Conceptual Analysis.” Conference on Autonomous Agents and Multiagent Systems.

Since you’re here…

…we have a small favor to ask. More people are reading SimpliFaster than ever, and each week we bring you compelling content from coaches, sport scientists, and physiotherapists who are devoted to building better athletes. Please take a moment to share the articles on social media, engage the authors with questions and comments below, and link to articles when appropriate if you have a blog or participate on forums of related topics. — SF

Great post!

I do believe the younger athletes do want it now rather than putting in the work and being patient.

Something that I see is more prevalent with Masters Athletes

Hi Jamy,

A great article.

Thank you