In strength and conditioning, various silos host more misconceptions than others and none more heavily debated than the ones surrounding women in resistance training and weightlifting.

Biology and human movement have been studied for centuries, but there are those who continue to think that weightlifting will cause infertility in women. Other misconceptions are more perspective-based, like the opinions that being strong isn’t feminine or that there is a higher risk of injury. In this article I will take you through these three common misconceptions that women—specifically in Olympic weightlifting—are often told and explain why they aren’t true.

#1. Reproductive Health

The risk of infertility is one of the most common reasons I hear about why women shouldn’t lift heavy weights. In some cases, when doctors learn of a female patient’s new training plan, they are met with the caution “don’t go too heavy,” citing the notion that it can disrupt their hormones and lead to reproductive issues.

Infertility is something many women struggle with, and it shouldn’t be taken lightly. Hormone production—specifically estrogen and testosterone—increase and decrease throughout the various phases of a woman’s cycle. The amount that is produced depends on the lifestyle and health history of the individual. And yes, exercise, especially heavy weightlifting, does play a role in hormone production as well.

Coaches should be familiar with the female triad: menstrual dysfunction, low caloric intake, and low bone mineral density. This is a dangerous form of exercise-induced amenorrhea, which can lead to poor hormone production and cause ovulation and fertility issues if unaddressed. A woman should not lose their period for months or years on end—but, lifting heavy is not a singular cause. Women who alter their menstrual cycle to this degree tend to have a low bodyfat percentage and are often malnourished, continuing to undereat while enduring strenuous hours of training.

Olympic weightlifting demands adequate nutrition to fuel the body in preparation for intense training days. The energy expenditure demanded in this sport does not allow for a woman to train in a deficit over a long period of time. The exception is a weight cut in preparation for a competition (and in this instance, the deficit wouldn’t be long enough to eliminate the menstrual cycle entirely). A weightlifter’s goal is never to see how low they can get their bodyfat percentage. Sure, there are weightlifters with lower bodyfat percentages than others, but due to the nature of the sport, that is a byproduct of that specific athlete.

Olympic weightlifting demands adequate nutrition to fuel the body in preparation for intense training days, says @nicc__marie. Share on X

Incontinence, although not specifically related to fertility, is commonly seen in women and is caused by a weak pelvic floor. From Olympic weightlifters to marathon runners to the sedentary woman, this issue is far more common than women realize. More importantly, there is something that can be done. Incontinence is not as simple as “do more Kegels.” The pelvic floor muscles work in conjunction with the diaphragm and often it can be a breathing and bracing issue that is causing the pelvic floor muscles to relax at the wrong time. Just like you can train your quadriceps to get stronger, the diaphragm and pelvic floor muscles can be retrained to prevent incontinence.

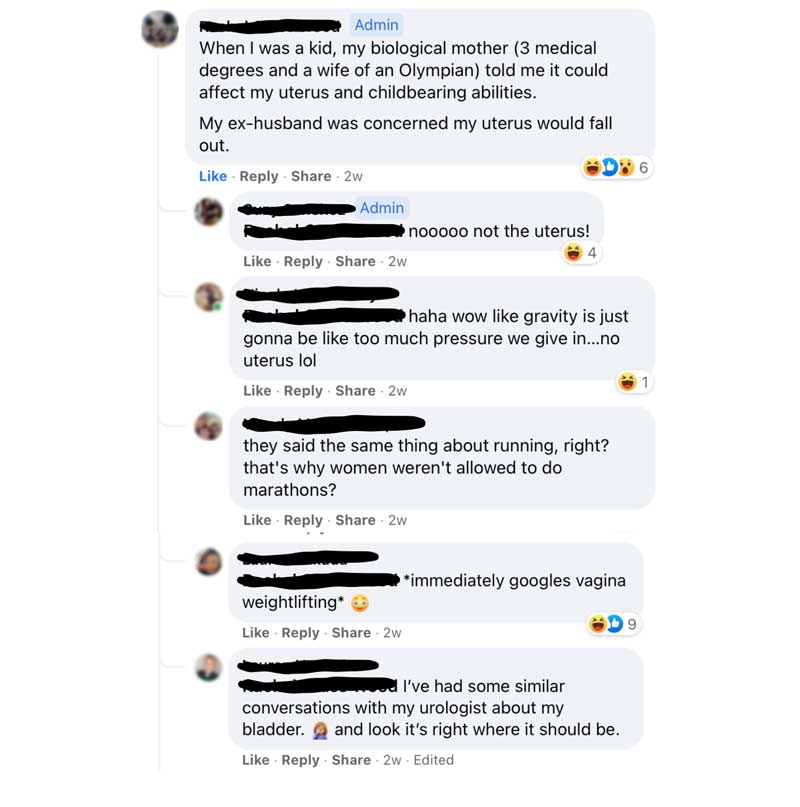

Just like you can train your quadriceps to get stronger, the diaphragm and pelvic floor muscles can be retrained to prevent incontinence, says @nicc__marie. Share on XWomen’s health is a growing field and physical therapists are beginning to study how to help their patients work to strengthen their pelvic floor muscles, engage their diaphragm, and help them work together. Bracing is another cause for concern if done incorrectly. Athletes often assume bracing means to bear down and squeeze their insides even though this is an incorrect way to brace and can be a cause of incontinence—I promise you this will not cause your uterus to fall out. Gravity will not take over and suck it out (yes that is something a woman was told).

2. Strong Isn’t Feminine

Some people don’t view women who appear strong and muscular as being feminine. Although this misconception might be more of a poor perception, it is interesting that women are still shamed into believing this. First off, women have always been strong creatures, enduring childbirth long before epidurals and hygienic delivery conditions were available. In the modern era, women have been proving that they can be strong and develop strength just as men can. They do not need a “female” catered workout to help them get stronger.

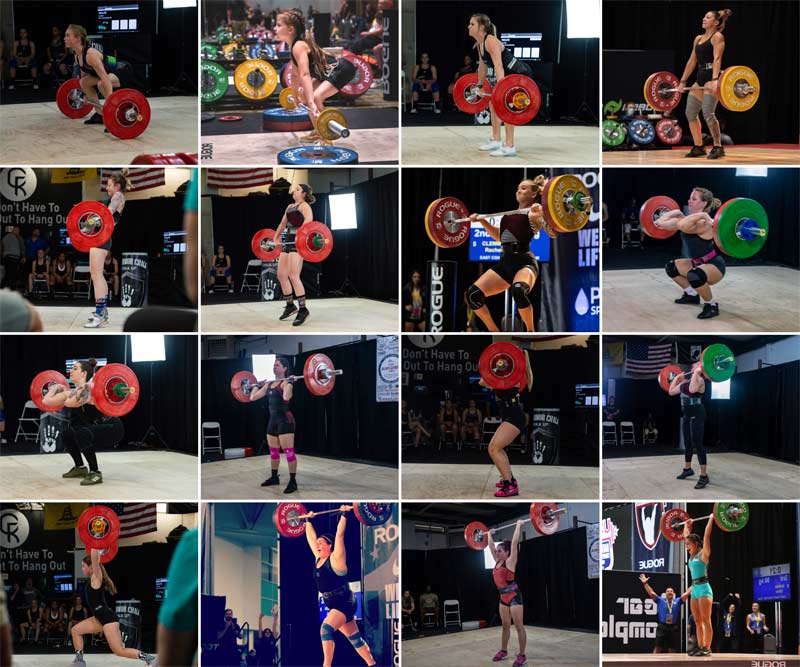

The strength and power phase parameters are the same among males and females. It’s also important to recognize that strength is shown in females of all shapes and sizes.

There are some women who don’t wish to look as defined or muscular as others. There is nothing wrong with this, but women shouldn’t be shamed for wanting to appear more muscular either. It does not make them any less of a woman. It is important to understand that if you don’t want that to happen, it won’t happen.

Nutrition plays a pivotal role in the muscular development and appearance for both women and men to obtain a certain physique. There is a discipline involved to become that lean, but it is not something that is required in Olympic weightlifting. I have worked with dozens of nationally competitive weightlifters in every weight class and watched their bodies change in and out of competition season.

Strength training will highlight their musculature because it will increase testosterone production, which in turn effects muscular tone and size. However, the visual difference that manifests when they are in a weight cut and preparing for competition, versus an out of competition training cycle, is based largely on nutritional discipline. The “shredded” or “lean” appearance that many will gawk at is a product of macro counting and a reduction of bodyfat and water in order to reach their competitive weight.

Nutrition plays a pivotal role in the muscular development and appearance for both women and men to obtain a certain physique, says @nicc__marie. Share on X“Bulky” is a common term that gets thrown around, but people need to understand that they are in control of that component. Sure, genetics will play a role due to natural hormone levels, but for the everyday female weightlifter, stop thinking that lifting anything over 15 pounds is going to turn you into Arnold Schwarzenegger—it won’t!

That’s the beauty of this sport: you can compete wherever your body feels comfortable sitting. You can control the amount of muscle size you gain and the amount of bodyfat you shed. From the casual weightlifter who incorporates the lifts into her training, to the competitive athlete within the various weight classes, all female weightlifters look different. There is no one mold to fit to be an Olympic weightlifter. In fact, some women have to eat to fill out a certain weight class or compete heavier than they normally sit (for example, Mattie Rogers at the 2020 Tokyo Olympics).

And unless you have an opportunity to compete at a national or international level, major weight cuts should be the furthest thing from your mind. I know that might ruffle a few feathers, but I will die on that hill. Unless a qualifying total is in reach, it literally doesn’t matter. Go lift weight and have fun.

To another end, if a woman decides she doesn’t want to continue with an intense training lifestyle, it’s okay to transition out of it. A woman’s muscles will not simply turn to fat the minute they stop lifting heavy (yes, someone was once told this.) Muscles atrophy, they don’t transform into something different. The important thing to take away is that as this sport grows and athletes such as Kate Nye, Jordan Delacruz, Meredith Alwine, and Sarah Robles continue to claim their rightful place in the history of strength sports, they will continue to inspire the next generation of young females. Strong can be anything you want it to be, and it most certainly is feminine.

#3. Risk of Injury

What is probably the biggest misconception revolving around Olympic weightlifting is the dangers and risk of injury due to the technical demands of the lifts—and this is true for men and women. The research has been done, and as long as it is supported by proper coaching and programming, Olympic weightlifting is no more dangerous that contact sports. The severity of an injury will vary, but the likelihood of those catastrophic injuries occurring is much greater in more traditional sports.

The research has been done, and as long as it is supported by proper coaching and programming, Olympic weightlifting is no more dangerous than contact sports, says @nicc__marie. Share on XOlympic weightlifters are taught how to properly miss a lift. The athlete has more control of their surroundings and movement patterns without having to respond or react to another person; meanwhile, traditional sports will see more acute injuries from a quick traumatic event where force or pressure couldn’t be managed. Weightlifters are more likely to experience chronic injuries from repetitive forces or tissue overuse. These injuries are much less severe and require a shorter time away from training. More importantly, when diagnosed and managed, the tissue can clear up and future issues can be minimal.

As it relates to women, there are misconceptions that heavy loads will be more damaging to a woman’s bone health and soft tissues due to more laxity in the connective structures. Women commonly struggle with calcium and vitamin D deficiencies and are more likely to develop osteoporosis and arthritis. But consider Wolff’s Law: the stress applied to the bone creates more durability. Lifting heavy will improve bone densification. Women do tend to have more laxity in their connective tissues; and, yes, too much mobility without proper stability and control can be dangerous. But the same way an athlete can train to be more mobile, an athlete can train to be more stable.

In either case, if the Olympic lifts are something you are interested in trying and safety is a concern, that’s okay. Reach out to a coach for knowledge and guidance to help you understand the lifts in relation to your body.

Ask the Right Questions

Whether the basis is biological, physical, or technical, misconceptions will continue to surround women in Olympic weightlifting. What’s important is that there are more women who are willing to call BS on it all! Remember to do your research and ask questions.

We are learning more and more about exercise and health as it relates to women every day. And if we can stop gaslighting with these misconceptions to scare women off and into a poor relationship with a cardio machine, then we might end up with some incredible generations of lifters in the future.

Since you’re here…

…we have a small favor to ask. More people are reading SimpliFaster than ever, and each week we bring you compelling content from coaches, sport scientists, and physiotherapists who are devoted to building better athletes. Please take a moment to share the articles on social media, engage the authors with questions and comments below, and link to articles when appropriate if you have a blog or participate on forums of related topics. — SF