I have the opportunity to work with a number of female athletes at the NCAA Division I level, specifically young women competing in softball, track & field, and rowing. Through this experience, I’ve gained a certain perspective regarding various groups of young women who are incredibly devoted to their sports—in some cases, they are competing at the collegiate level as the culmination of 10-15 years of commitment and dedication to their given event. With regard to rowing, they are often beginning a new athletic endeavor altogether!

All too frequently with these female college athletes, their sport-specific skills are highly developed, but take the glove out of their hand or the spikes off their feet, and the weaknesses in their athletic foundations are quickly exposed. (Many coaches will recognize that these observations are not unique to female competitors, either.)

Can You Learn to Train, Compete, and Win All at Once?

Young women’s athletic careers are often too quickly shunted into being competitive, with little time dedicated to developing fundamental movement skills, foundational strength training, or any sort of structured athletic development outside of sport-specific practice or competition. It’s as if they must constantly prove themselves, and are being tested to see what they can do and how they compare with one another. This leads to games, then tournaments, traveling across the state and across the country, and club season in the summer and fall, with their respective high school season in the winter and spring.

We need to give young female athletes the chance to maximize potential that we do for male athletes, says @Cody__Roberts. Share on XFrom my perspective further down the line, it seems incredibly overwhelming and backwards. From a pre-teen age, we ask these young ladies to compete against one another with a high standard placed on winning, without ever engaging or prioritizing the ancillary pieces to performance enhancement and injury prevention through proper training, development, and education.

Don’t get me wrong—I understand that a sense of team camaraderie and competitiveness can be an important ingredient in this process. But then here on campus arrive 18-year-old young women who have little to no experience with strength training, or with having properly prepared their bodies and minds for the demands of practice, holistic training, and competition.

It may be a chicken-and-egg discussion, but I make this challenge to all parents:

- Are you making the time for your daughter to learn how to train?

- Is she playing other sports or doing other activities besides her primary sport?

- Is she allowed a true off-season?

- Does she have a true “off” day during the week?

As a strength and conditioning coach, I’m obviously partial to the mental fortitude that comes alongside the physical development from learning to squat, deadlift, lunge, press, and pull, with or under a load.

This is not to say that underdeveloped and overspecialized athletes are always the case: School districts often employ certified strength coaches (or contract out to private professionals), while CrossFit, social media, and more have all greatly increased the popularity of strength training and the use of the barbell. This can make a collegiate strength and conditioning coach’s job somewhat easier, smoothing the acclimation process of teaching an athlete how to lift properly and use free weights. (Properly can have different meanings to different people…but that is not the road I want to go down with this article.)

Overall, each individual teenage athlete will fall somewhere across a wide spectrum of experience that must be appreciated when they step on campus. Within the same group of freshmen student-athletes:

- Some may have been involved in structured strength and plyometric training since adolescence with a quality and experience professional;

- Some may have had a physical education class in high school and a football coach that let everyone do the program their football players were doing;

- Some may have been constantly playing their sport(s), traveling to tournaments, and participating in showcases, with a nonstop practice schedule and no commitment to proper or adequate strength training.

Let us focus our attention on that last end of the spectrum, with the athlete that has little to no experience in the weight room. They are possibly a victim of the youth and club sport system that puts a high priority on traveling to compete in tournaments every weekend, limiting the opportunity to dedicate time to enhancing performance potential and mitigating the risk of injury through basic strength training. Or maybe they simply never had the opportunity or encouragement necessary to step into a weight room with proper guidance? In the end, it is definitely not the student-athlete’s fault, as they are at the mercy of their environment and the system. I would encourage youth athletes to enjoy what they do and do a variety of activities (sports, exercises, games, etc.).

Too often there is this standard on competing, winning, and individual accolades. But this process can be very detrimental, because the athlete never puts in the necessary time for training and doesn’t learn to appreciate the work and commitment needed outside of game day. It is the work in the weight room, on the track, and outside the lines of the playing field that provides a foundation of both mental and physical development for a young athlete.

Things are shifting and evolving, but I hope we, as coaches, and especially at the youth level, provide an opportunity for young women to maximize their potential and development much as we do with male athletes playing football, basketball, wrestling, or baseball. A weight room can be a male-dominated environment and can be terrifying and intimidating for a young adolescent, and girls cannot be treated as boys that don’t lift as heavy. Fundamentals may be the same in the movements, but the approach needs to be adapted to the individual and personality.

It is our responsibility to bring guidance, welcoming women into the weight room at an earlier age, says @Cody__Roberts. Share on XScience and research have shown that per unit of muscle, potential for strength is equal across genders (women can potentially make greater improvements in strength in the short term) and women can build muscle at similar rates to men1. We may know this, but young athletes are not reading this research and it is our responsibility to curb these doubts or fallacies and bring guidance, welcoming women into the weight room at an earlier age. Further, the research and encouragement around youth strength training and the benefits, especially for a post pubescent female, are astounding when it comes to performance enhancement and injury prevention3.

Control the Controllable

Regardless of the youth system, as strength and conditioning coaches—especially at the collegiate level—we are left to assess, adapt, and adjust our training philosophy to quickly onboard and maximize the time and efforts of the student-athletes who are our responsibility. An effective coach is one that can rapidly acclimate an inexperienced athlete to the weight room. As Carl Valle wrote in a recent barbell squatting article: “We shouldn’t overcoach, but the blend of teaching and challenging an athlete with tasks is an art worth exploring.” Helping the athletes understand proper technique and educating them on how strength training can impact their ability, durability, work ethic, and commitment—this is the psycho-physical side to training. The physical actions and techniques are important, but more important is the psychological approach to the general process and each training session (and, when it comes down to it, each set and repetition).

Over time, the technical cues, progressions, and programming may become more simplified and more easily understood in the eyes of the strength coach. However, what never gets easier are the personalities and the people, as each individual presents new and unique trials and tribulations. Herein lies the art and science of being a strength coach, where it is challenging, but at the same time incredibly rewarding, to see the growth and maturation of any young student-athlete, male or female.

S&C coaches are responsible for molding not only an athlete’s body, but more importantly their mind, says @Cody__Roberts. Share on XThere is no recipe for success, and it takes time and effort to slow-cook an athlete to buy into training and simultaneously compete at the NCAA level. When all is said and done, strength and conditioning coaches are responsible for molding not only the body, but more importantly, the mind of the student-athletes they work with. There should be pride taken in how an athlete conducts themselves in the weight room, and the strength coach is the driver of that bus.

Teacher & Coach

Back to our freshman female athlete with zero “weight room” experience. The first responsibility is to meet her at her level with regard to exercise prescription and ability. The proper exercise progressions and regressions that help set her up for success will be a vital piece to building trust and confidence between coach and athlete. She may be intimidated by the barbell, the plates, the larger set of dumbbells—and even though her legs may be strong, her grip is not equivalent yet, so starting small and simple is important.

But even with the simplest exercise, there are still at least a handful of technical cues that need to be understood and appreciated. This is where the coach becomes a teacher, aiding and guiding the focus to keys like posture, foot pressure, and intent on each repetition. In a large team setting, a coach only has one pair of eyes and one voice and cannot actively coach every individual through each repetition. But what a coach can do is simplify the technical cues and set the athlete up for success, teaching her what to remind herself or her teammates to do while performing every exercise.

A coach should identify three standard cues with each exercise:

- Stance/Setup

- Grip/Bar Position

- Bar/Body Action

For example, for a Goblet Squat:

- Stance: Shoulder width

- Grip: DB/KB at sternum, with forearms actively squeezing the weight

- Body Action: Sitting hips between the feet, maintaining an upright posture and full foot pressure

Even simpler than a Goblet Squat, a Counterbalance Squat or Lateral Squat, where the arms extend out from the body and allow the hips to counter backward, keeping the arms parallel to the ground and the torso upright. This exercise is a great way to autocorrect position and action, allowing the coach to assess abilities and limitations with regard to movement quality. The simplest of activities in the weight room can help acclimate athletes and reduce the intimidation factor associated with the space.

Simple activities in the weight room can help acclimate athletes and reduce the intimidation factor, says @Cody__Roberts. Share on X’Starting Strength’

The exercise end goals I reference in this article all center around the barbell—in my mind the primary static strength exercises. Multi-joint in nature, they are the “best bang for your buck,” allowing the athlete to handle the heaviest loads and having the tried-and-true greatest return on investment. These are the squats, deadlifts, and presses with a barbell. These lifts do not always start with a barbell (as is the case with squatting), but the barbell is the goal.

This is another nugget I appreciated from Carl’s barbell squatting article—“Heavy training is the ultimate teacher”—and in the progression of athletic development, there will come a time that it becomes a necessary piece. But with heavy barbells comes great responsibility, and what makes these exercises so potent is that if an athlete wants to truly embrace their greatness and reap their benefits, a solid mental and physical approach is necessary. These exercises create the strength and skill needed for an athlete to operate at higher levels with Olympic lifts (cleans, snatches, and jerks), and, ultimately, the ability to create force in other skills and sports.

Crawl, Walk, Run (Progression)

A coach can improve their ability to effectively coach and impact a group by controlling the tempo of each rep. Starting slow can be effective, and this accentuated eccentric focus has training benefits as well, especially for a beginner. This approach improves the neuromuscular connection and provides the mechanical tension necessary to create the desired adaptation and motor learning.

Controlling the eccentric phase of each rep allows the athlete to better feel the positions and actions she is going through: Connecting coaching cues with mindfulness and focus; learning to create tension and stiffness throughout the torso, upper body, and lower body; creating this concentration and appreciation for technique; and focusing not so much on counting repetitions, but on making each rep count. This is the first step toward developing maturity in training, instilling diligence and treating each multi-joint exercise as a skill—not to mention it also helps prevent putting too much load on the bar too soon.

Any variation of tempo, such as pausing prior to the concentric action, can be valuable. It continues to challenge the athlete and provide variety, and is all part of the pursuit of mastery in building a wide base of physical and mental understanding for a specific exercise.

I rarely say never, but I never promote an accentuated concentric action, as there are no benefits and it can confuse the athlete as to what the goal is regarding moving the load. There are always exceptions, and there may be a time that the athlete needs to go slower on the way up to build confidence and establish control, but I am not going to be the one to control or limit that. Let the athlete develop a sense of overcoming gravity on their own. When the time is right and in the effort of progression, add velocity-focused training after technical mastery and rudimentary strength is established. This can be very valuable, since it promotes intent, provides immediate feedback, and can be a way to take focus off of load and facilitate competition through moving moderate loads aggressively between teammates. But as I said, when the time is right…

Another way to increase use with a barbell while governing the load is to prescribe some sort of barbell complex (three to five different exercises performed consecutively without putting the barbell down).

Barbell Complex– RDL, Hang Clean High Pull, Hang Clean, Front Squat x2 – five each

This can be used as a warm-up at the beginning of a session or cool-down activity to help establish technique. At the end of the session, things can often be incredibly productive as minds and bodies are their most alert and mobile for this type of work.

Never Sacrifice Technique for the Weight on the Bar

Technique is always the priority, for safety purposes as well as the discipline and accountability piece mentioned earlier. We never want to fool ourselves or the athletes we work with into thinking they are getting stronger by increasing loads at the expense of either shorter ranges of motion, or sloppy technique. This is when we are driven by ego, and chasing numbers rather than focusing on the “Learn to Train” phase of development. Competition can be a great thing, but check your ego at the door and focus on the progress, not the performance under the bar.

Focus on progress, maintain perspective, and above all, stay true to the technique, says @Cody__Roberts. Share on XFor beginners, things will happen and progress quickly, and it is often too easy to bite off more than they can chew. Use your experience, knowledge, and maturity as a coach to help keep the reigns tight on these young and excited minds. Maintain perspective and stay true to the technique. Instilling this patience and appreciation will pay dividends, and most importantly, when the athlete trains away from your supervision they will have their concentration and effort in the right place.

As the basic technical cues are understood and loads begin to increase, there can be layers of technical cues that need to be added. The stance, grip, and body action that got them started will always remain, and you should work to connect consistencies to any and every exercise or sport-specific skill. As the loads begin to challenge posture and the position of the joints and spine, this is where we add in advanced components of bracing and positioning that initially happened on their own, but now need additional cuing and regard. This can be a focus on engaging or using the upper back, head/chin position, in maintaining a neutral neck, or position and focus on knuckles, wrists, and elbows. All are potentially one-inch adjustments that have incredible return on safety and performance in the respective lift.

Further, the use of diaphragmatic breathing and the Valsalva maneuver can also be learned during this time and should flow well, as philosophically the use and cuing of breathing through the diaphragm happens concurrently in warm-up, corrective, or torso exercises as well. This is in effort to avoid the use of a belt and to promote proper bracing. It may be a philosophical opinion, but I am not one to encourage wrapping a belt around an athlete to help them handle a heavier load. In the end, we want to progressively load and this is a technique and means to accomplish that which will have greater transfer to their sport (where they will not be wearing a belt either)—empowering the athlete from within to transfer strength and power from the lower body to and through the torso and upper body/barbell.

I measure my impact on athletes on the way they conduct themselves without my instruction, says @Cody__Roberts. Share on XUltimately, each set and every rep is a tuning process, developing physical proficiency as well as mental fortitude. Identify two to three cues that the athlete understands, and implement these as she sets up under or on the bar and attacks the set mentally and physically. This is training: the practice and rehearsal of a task that challenges the individual and helps facilitate change. In order for that change to stick, there has to be mental engagement. This is the “teaching” and “challenging” side to coaching that must be instilled in athletes. I measure my impact on athletes on the way they conduct themselves without my instruction and take great pride in how they operate and conduct themselves in a weight room.

Progress Is a Process

Strength and conditioning coaches have the opportunity to not only improve performance and physical output, but—more important and more impactful—the molding of the athlete’s mindset and approach to training. There is so much to be gained from strength training, and the barbell will never lie. Training, like life, is a place where you cannot cut corners, and the greater the investment, the greater the return. The investment is not measured in how much you do, but rather in the focus you do it with: “train smarter, not harder.”

As an athlete learns to train, it is the responsibility of the coach to encourage patience and a focus on progress over time, taking away the focus on load. Again, dipping to the “art” of coaching versus the science, but building trust with the athlete allows them to gain confidence in their preparation. When an athlete sees steady progress with the barbell, in their body, and on the field, then they will continue to become more mentally engaged in the process.

Progress with a Purpose

Once technique is established and the periodization of training ensues, a layer that helps to promote progress with our athletes is to give them purpose in how to load. I generalize my weeks of training into four categories:

1. Base: This is the introduction of the exercises and a feeling out for what loads can be handled.

- During this session, the athlete focuses on establishing technique as well as challenging reps per set, setting an understanding for the weeks ahead regarding how much she can handle.

2. Volume: This is where we stabilize the weights used in the base week and look to increase the amount of work being done.

- This is another opportunity to potentially add the RPE layer of training.

- Help the athlete understand Rate of Perceived Exertion, as during this week RPEs should be roughly an 8 (2-3 reps left in the tank, nothing to failure).

3. Intensity: This is where the athlete looks to increase the weights used and volume (sets or reps) decreases.

- Coaches need to pay the most attention here, keeping egos at the door and continuing to promote technique as the priority.

- Reinforcing the RPE concept, we can start to explain and understand RPEs of 9-10.

4. Unload: Intensity is generally maintained during this week, but volumes (usually reps) are very low.

- This serves as a way to stabilize the intensity of the bar and gain confidence operating with the newfound loads and abilities from the previous session.

- As a coach, watch the speed and technique, and reinforce that the RPEs should be in the 6-8 range. Combine telling the athlete with allowing the athlete to feel and tell you how they would rate the sets they perform.

It is such a beautiful process as it unfolds and the athlete (female or not) comes into the room with an established understanding of proper technique, and knows how to appropriately apply that technique and balance the workload as it fits into the holistic picture of their sport, season, and development.

Facilitating Engagement

As much as the focus has been on molding the mind of the individual athlete, much of what we do in sport is team-related and team-focused. To be effective coaches, we must also facilitate the engagement, conversation, and interaction of our student-athletes during a session. What they are doing is difficult, and often not the most enjoyable (early mornings, at the end of a hard practice, etc.). The best way to not simply get through, but to truly get better, is to support one another. Hold each other accountable to the techniques everyone is collectively learning, ask questions, provide feedback, and be encouraging for each rep and set.

There needs to be an understanding that the time is now, and in order to truly benefit from the training, there needs to be an urgency, purpose, and motivation through the process. This does not mean that loud music, yelling, screaming, and slapping each other is the answer. But just as any artist would approach their craft, things need to be methodical. An effective coach helps the athlete and team navigate this system and approach, which can be done in part by leaning on the veterans and upperclassmen of the group to help continue the standard and on-board the freshmen.

The athletes I work with are technicians with the barbell, and I work to help the athletes develop a routine and checklist for how they begin each set and perform each rep. Even in the lighter/warm-up sets, no matter the week or session, there is an “act as if” mentality. So, psychologically, when the athlete begins to handle loads that are 85%+ their 1RM, they already have the mental maturity for how to operate and what to think about, and they are set up for success and progress.

More than telling athletes they should care, create an environment that makes them wantto care, says @Cody__Roberts. Share on XThere is a mental switch that gets flipped as soon as they grip the bar, and a focus that carries over into their sport and life. It is much more than simply telling them they should care, it is creating an environment that makes them want to care. They care because they see the results of others before them, they see their own results, and they have dreams and goals of success. Help them unlock their potential and aid in the maturation process from learning to train to training to win.

Timing Is Everything

The primary piece to be understood is that this is not a recipe where you can simply mix all the ingredients together at once and have everything come out of the oven as you envisioned. We must add each ingredient at the right time and in the right way to get the product and reaction we wish. This is where the art of coaching outweighs the science, and is what truly makes a coach effective in their craft. The best training program is the one that athletes believe in. The psychological feeds the physical—the greater their investment, the greater the return.

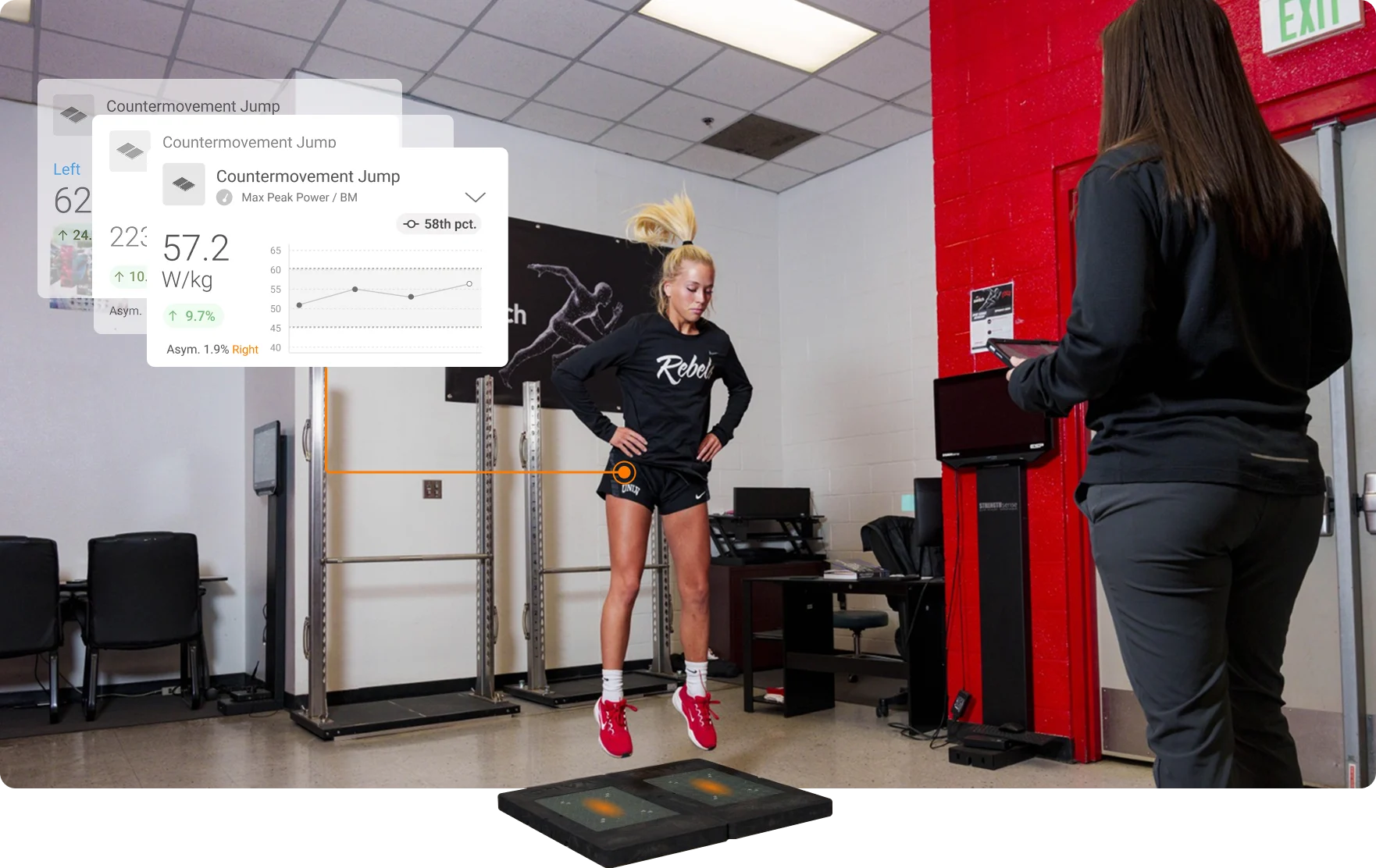

The best training program is the one that athletes believe in, says @Cody__Roberts. Share on XA coach must first know where they are going: meaning, what exercises they ultimately want to get to and what qualities they want to develop. Use the proper exercise regression that allows progression to the barbell exercises you are working towards. Establish technique and continue to add layers of understanding and mastery as the confidence of the female athletes increase, along with the weight on the bar and in their hands. Show them the transfer of training as performance in other areas begins to grow (speed, vertical jump, etc.); develop their trust and buy-in. Make them feel as welcome and important as their male counterparts.

Ultimately, give them purpose and ownership of the process as they fully engage both mentally and physically with their time and efforts. We are not looking to create weightlifters or powerlifters in this process, but we are developing values and skills that they can implement in all areas of their life. Iron sharpening iron, tough and together.

Since you’re here…

…we have a small favor to ask. More people are reading SimpliFaster than ever, and each week we bring you compelling content from coaches, sport scientists, and physiotherapists who are devoted to building better athletes. Please take a moment to share the articles on social media, engage the authors with questions and comments below, and link to articles when appropriate if you have a blog or participate on forums of related topics. — SF

References

1. Best Strength Training Articles – Stronger By Science

2. Long-Term Athlete Development Framework, Sport For Life Canada.

3. NSCA Position Paper: The Squat Exercise in Athletic Conditioning: A Position Statement and Review of the Literature National Strength & Conditioning Association Journal – 1991