This article was co-written by Derek Hansen and Robert Panariello.

Sports are such a big part of our culture, and not having an event to attend or watch on television due to COVID-19 shutdowns has left a significant void in our lives. This void is accentuated when people are cooped up in their homes without an outlet for their emotional energy. Those who work in sports—including athletes, coaches, and the staff of professional teams, sport institutes, universities, and high schools—are all dealing with an equal void because their professional lives have been significantly disrupted until further notice. They aren’t permitted to go to work and put in the long days of training, effort, and preparation leading up to a season. Some competitive seasons were interrupted mid-stream, and it’s uncertain whether those seasons will be adequately concluded, including post-season events. Everyone is left feeling empty and helpless, hoping the outbreak will subside so they can soon resume normal routines.

We’re all hoping that continued tragedy and loss of life can be averted in the coming weeks and months ahead. It may take significantly more time before governments are prepared to allow people to gather and resume their normal daily routines. For professional teams, this will include practices, meetings, rehabilitation visits, and workout sessions. While it may not initially include fan attendance in stadiums and arenas, the first order of business will be to allow teams to prepare as they normally would for a return. However, there are possible hidden risks for players as adequate training has been an uncertainty during the shut-down period. Rapid returns by teams to conclude playoff games may result in significant player injury that could impact numerous careers and livelihoods.

In this article, we provide guidelines for returning from the COVID-19 shutdowns and the possible consequences on both player performance and health as part of the return-to-sport process. We’ve already been working with many professional teams and universities to prepare for such circumstances, consulting with them about various scenarios and contingencies. We want to ensure we maximize player health while establishing rational and pragmatic guidelines around performance training and sport-specific practice. While there is no perfect way to handle this matter, we must focus attention and care on the preparation and requirements for both sport training camps and competitive demands when returning from a health crisis never experienced before.

The Reality of Training During COVID-19 Restrictions

It’s no secret that an athlete’s training during the COVID-19 pandemic has been difficult at best. Depending on which part of the country you reside in, restrictions can vary from strict orders to avoid public spaces to not gathering at private facilities located on school and university properties. As all gyms are closed, most athletes can’t participate in optimal weightlifting. The professional athlete who has a home gym might be able to accomplish their appropriate workouts, but this likely includes a small percentage of athletes. If they’re confident to go outside, they may be running on a sidewalk or street, though optimal training distances could be limited. The swimming athlete faces greater challenges to replicating their regular training sessions and can only attempt to preserve their basic physical qualities. To state the obvious, training with peers is definitely out of the question, unless they live with you. We are now fully realizing the physical, psychological, and social realities of training during a global pandemic.

We now understand the realities of training during a global pandemic and must assume that training qualities are deteriorating. Share on XTherefore, we must safely assume that all training qualities are deteriorating during this time. The magnitude of this detraining phenomenon will vary from athlete to athlete depending upon genetics as well as how much mitigation training they perform via bodyweight, resistance band, and modified running programs received from their coaches. The longer COVID-19 distancing measures continue, the deeper the hole dug. Realistically, all plans moving forward after this pandemic must take into consideration the depth of this deconditioning hole. It’s also unlikely that any return to normalcy will transpire rapidly. It’s more likely that a phased approach will be instituted when returning to normal daily activities. Gathering in large collective groups probably won’t happen as quickly as sport coaches, staff, and athletes desire.

We have the time now to prepare our athletes against injury and ensure they're ready for competition once the COVID-19 measures are lifted. Share on XHow this presents may not be apparent to schools and professional teams until we have a few months of flattened numbers and regressing positive tests. Because of the uncertainty and the number of questions that remain, organizations must plan for every possible eventuality. The positive aspect of this situation is that we have a good deal of time and availability to prepare for an optimal return to sport to ensure our athletes are both protected against injury and ready for competition. We must do the work now, however, to prepare us for later.

Implications of Detraining During Lockdowns for Injury Risk

Injury resiliency must be the highest priority for all organizations moving forward to a full return to sport. Due to athletes’ containment in a less than optimal training environment (i.e., home, apartment, absence of training facilities, etc.), an overall deconditioning of the physical qualities of the body, including the athlete’s work capacity, will likely occur. A deficiency in work capacity could set the stage for overuse soft tissue injury (strains, sprains). And excessive fatigue may result from limited work capacity, as demonstrated by an athlete’s inability to maintain optimal and consistent physical and mental performance during high-intensity sport practice sessions. The onset of excessive fatigue places athletes at the following physical disadvantages:

- Diminished optimal and consistent repetitive muscle force (strength and explosive strength) quality output

- Poor reactivity to the ground surface (i.e., propulsion, deceleration, change of direction)

- Diminished kinesthetic and proprioceptive awareness (i.e., foot and hand placement when moving at high velocity)

- Diminished ability to concentrate on specific tasks during the practice session

- Diminished ability to optimally physical recover after repetitive maximal efforts

- Diminished ability to optimally physical recover between sport practice sessions

Maintaining (or re-establishing) an athlete’s physical condition is imperative while they’re residing in a contained environment. HOF S&C coach Al Vermeil’s hierarchy of athletic development is one option we can use as a guideline for an athlete’s “home” COVID-19 training sessions to help them achieve as optimal a physical development as possible. The initial focus for the athlete’s work capacity in our current restricted training environment will give them the ability to maintain consistent, repetitive performance until the time return to sport arrives. An appropriate work capacity also allows for suitable recovery between maximal effort repetitions as well as sport practice sessions. There are various methods available to establish and maintain an athlete’s work capacity. One to consider for restricted training environments is the Javorek exercise complexes, which require minimal equipment (barbell, dumbbells) and training space.

The Javorek exercise complexes are the brainchild of Romanian S&C coach Istvan (Steve) Javorek. They incorporate two basic components: total body exercise performance benefits and work capacity enhancement. The complexes are traditionally performed with either a barbell or dumbbells and include performing 6 prescribed exercises consisting of 6 repetitions each for a total of 36 executed repetitions. One executed exercise immediately follows another to conclude 1 set or cycle. Initially, 3 cycles may be performed 3 times per week with an initial weight intensity of 15% bodyweight (BW) progressing over time to 5-6 cycles performed with a weight intensity of 35%-50% BW. You can review specific exercise complexes from Coach Javorek’s literature or his website. You can also modify the complexes according to an athlete’s medical history, needs, etc. The selection of exercises and the number of cycles should progress weekly. An example of a modified cycle includes performing the following exercise sequence:

- Mid-thigh pull X 6

- Muscle clean X 6

- Overhead press X 6

- Back squat or front squat X 6

- Good morning or RDL X 6

- Bent over row X 6

Javorek complexes assist in enhancing the following qualities:

- Work capacity

- Joint mobility and soft tissue compliance

- Exercise technical proficiency

- Neuromuscular development

- Strength levels

Once an adequate work capacity is established, the athlete needs to emphasize their strength levels. The physical quality of strength is the foundation from which all other physical attributes evolve. Stronger athletes have demonstrated faster sprint (i.e., 10, 20, and 40 yards) and change of direction times, deceleration abilities, and higher vertical jumps when compared to weaker athletes. Stronger athletes also demonstrate lower injury rates. Dr. Tim Hewett, who is well renowned for his ACL prevention research, has shown that weaker athletes are considered ligament dominant. In other words, they are more dependent upon ligament contribution for joint stability when compared to stronger athletes. With athleticism and skill levels being the same, the stronger athlete usually prevails.

While at home, athletes first must establish adequate work capacity (Javorek exercise complexes) & then enhance strength with bodyweight exercises. Share on XIdeally, we can enhance the physical quality of strength by applying an external unaccustomed high-intensity stressor (i.e., weights) during exercise. Some athletes may have limited, if any, access to high-intensity exercise equipment. And some may find themselves in circumstances where their BW is the only resistance variant available. These BW conditions will require them to play the preverbal “hand they are dealt,” needing maximal efforts to transpire during the exercise. The following are some recommendations for BW activities to enhance strength as well as improve the other physical qualities in Coach Vermeil’s hierarchy.

- Isometrics. Training with isometric exercise is beneficial in both the rehabilitation and performance training environments. Isometrics are used for reducing pain, increasing muscle hypertrophy (when performed at longer muscle lengths), greater neuromuscular activation (with ballistic execution), rapid force production, and increased recruitment of the motor unit pool available. They also improve muscle efficiency at submaximal loads and enhance oxidative metabolism. Guidelines for isometric exercise prescription are as follows:

- Hypertrophy: 70-75% max force, 3-30 seconds per repetition, 80-150 repetitions per training session performed at longer muscle lengths

- Strength: similar or higher forces as hypertrophy, 1-5 seconds per repetition, 30-90 repetitions per training session

- Tendon: similar to strength guidelines

- Ballistic isometrics are best performed for rate of force development (RFD)

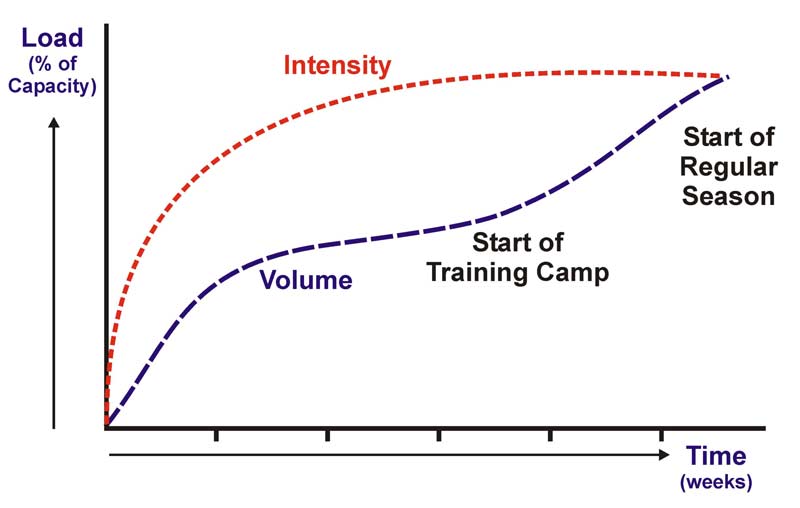

- Squats. BW squats and, more specifically, overhead squats ensure joint mobility and soft tissue compliance and help maintain and increase strength levels. Regardless of the squat variation used, this BW exercise should be performed at different tempos and with appropriate exercise depth. Although squat depth and applied external intensity go “hand in hand,” studies have presented squat depth as related to relative muscular effort (RME) during exercise performance. RME is the muscle force required to perform a task relative to the maximum force a muscle can produce. Concerning RME, squat depth is accentuated over intensity for quadriceps muscle enhancement. Squat depth was also found to be just as essential as applied exercise intensity for hip musculature strength development.

- Jumps up stairs. Most homes and apartment complexes have a set of stairs. Wooden staircases are better than cement ones due to the reduced ground reactive impact forces placed on the lower extremities. Single maximal effort jumps up a set of stairs will provide explosive strength efforts with associated low impact upon the body as each subsequent landing surface is higher than the step of the take-off surface. Multiple successive jumps up a set of stairs will also comprise reactive strength abilities.

- Lateral bounds. Although there are various track and field drills we can use during this COVID-19 time, it’s important not to exclude exercises for the lateral hip musculature. Lateral hip strength contributes significantly to the prevention of knee injury as well as athletic postures necessary during high-velocity performance. Our good friend Dr. Donald Chu would test his athletes by performing a single maximal effort lateral bound on a standard track. He taught us decades ago that athletes who cover the greatest distance laterally (the most track lanes) likely have the fastest linear velocity.

- Sprinting. Sprinting will occur outside the home while athletes adhere to social distancing. Sprinting is the purest of all plyometric activities and includes all physical qualities in the hierarchy. Sprinting also maintains and enhances the athlete’s linear velocity and work capacity. An often overlooked benefit of sprinting is the establishment and maintenance of the neuromuscular timing of the hips and lower extremities that’s necessary for both injury prevention and optimal athletic performance for high-velocity movement. Take caution if sprinting activities take place on cement or asphalt surfaces (sidewalk, street, parking lot). These surfaces are not very forgiving and are extremely taxing on the body. Performing work up a slight hill or incline, as well as reducing overall volumes of sprinting on a hard surface, will go a long way to minimizing impact stress and overall eccentric load on the body.

Program all exercise performance safely and based on the athlete’s medical history, training history, present physical condition, and environment available for training. The program design should also include a prescription of maximal executed exercise efforts.

Exploring the Concept of a Reverse Taper for Return to Sport

Once teams and sports organizations determine an appropriate return-to-sport date, we’ll need to draw up plans to prepare the athletes in a conventional setting to ensure they’re physically, psychologically, technically, and tactically prepared for an effective resumption of sport. Let’s be clear, though—we have no idea what this will look like since it’s uncharted territory. We don’t know if there will be restrictions on group gathering size, duration of sessions, differing requirements for indoor versus outdoor sessions, virus testing requirements, and many more logistical details that may be phased in over time. We can only approach this from a known position: returning to sport as we previously knew it. If athletes are allowed to return to their professional team facility or university campus, how would this look in terms of providing safe and effective training, COVID-19 restrictions aside?

We’ve been proposing an approach to prepare athletes both adequately and expediently. We also acknowledge the reality that different leagues may not provide enough time to prepare for resuming a season or introducing post-season play in a condensed format. Given that the road back to high-level, competitive sport is laden with many challenges, we must adopt a strategic approach to minimize the risk of injury.

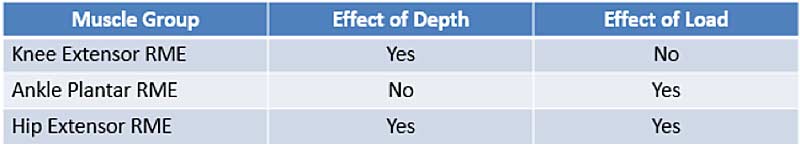

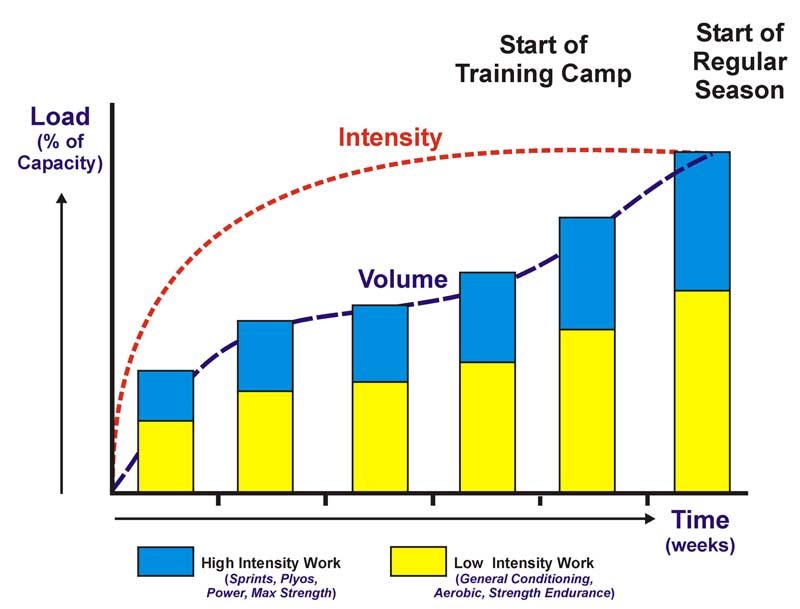

Since the road back to high-level, competitive sport is laden with many challenges, we must adopt a strategic approach to minimize the risk of injury. Share on XWhile the conventional approach to improving athletes’ physical qualities traditionally has involved gradually introducing both volume and intensity over a protracted preparatory period, volume has typically increased at a greater rate than intensity. Higher volumes of work with reduced recovery times often go a long way to naturally limiting output intensities, whether they involve strength, power, or speed. While this approach allows for general fitness qualities to improve in a relatively linear fashion, we can limit exposure to higher intensity training elements such a sprinting, jumping, and weightlifting until the end of the preparatory period. This is illustrated in Image 1, with not much volume accumulated at these higher intensities. This phase is typically followed by a specific preparatory phase where we accrue larger volumes of high-intensity training for both performance and injury resiliency.

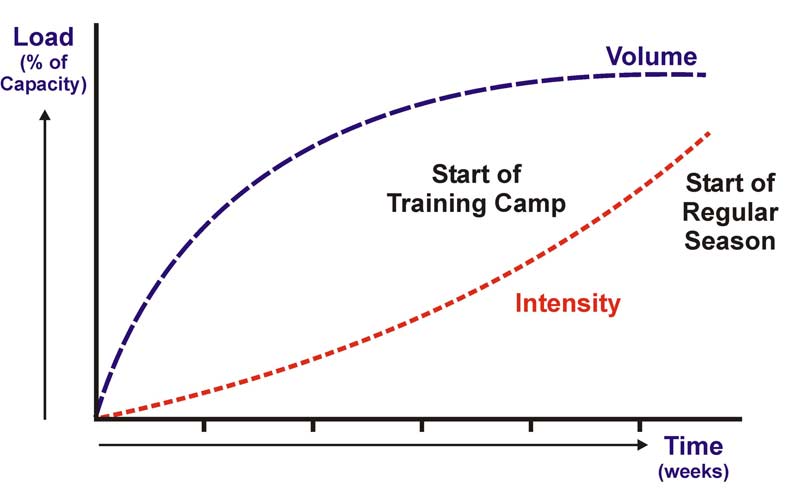

When time is in great supply, the conventional approach to loading can be quite effective at limiting exposure to risk and gradually accumulating safe volumes of work. However, when time is constrained, we must consider alternative strategies. Our experiences with Olympic athletes in track and field, swimming, and cycling has demonstrated that high-intensity work can be maintained—albeit at lower volumes of work—as part of the taper to peak competition to maintain athlete readiness while keeping them fresh and recovered, as illustrated in Image 2. These tapers can often occur over 7 to 14 days—a relatively short timeline leading up to a major competition—with significant results.

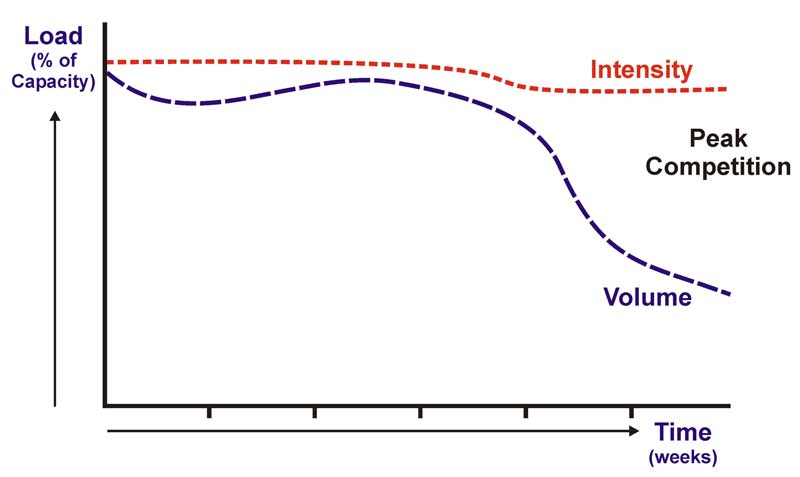

Extending our competitive taper concept and understanding that high-intensity work can be introduced and tolerated at lower volumes of work, we decided to reverse the direction of the taper with some of our professional team athletes to ensure they were prepared and ready for the shorter preparatory timelines experienced in pro sports.

We successfully reversed the taper with team athletes so they were prepared for the shorter preparatory timelines experienced in pro sports. Share on XThe example illustrated in Image 3 depicts a scenario where athletes have a two- to three-week preparatory period before a two-week training camp leading into a competitive season. We introduce very low volumes of tolerable high-intensity work throughout the micro-cycle to make sure the athletes are exposed to these stresses relatively early in the preparatory period. This allows athletes to accumulate high-intensity work from the first week onward, inoculating them against the risks of higher velocity and higher load activities they may experience in training camp and the competitive season.

The efficacy of any stress inoculation program is to determine the optimal dosage and exercise prescription for the early phases of the preparatory period. Given our proficiency with both sprint work and plyometric activities, we devised training programs that took advantage of short-accelerations and medicine ball throws in low doses but relatively high frequencies in the early stages of the return-to-sport preparatory program and had great success.

Image 4 illustrates the distinction between the proportions of high-intensity training elements (i.e., sprints, throws, jumps, lifts) and low-intensity components (i.e., general conditioning, strength endurance, aerobic endurance) that can vary subtly throughout a preparatory period. On average, the proportion of high-intensity work to low-intensity work may be in the order of 40% to 60%, give or take 5% for the preparatory phase. Older athletes may limit exposure to higher intensity work and modify the ratio to 30:70 or 25:70 (high:low) given their longer recovery requirements and overall “mileage” on their odometers. Understanding the distinction and allocation of these work classifications is important for maximizing comprehensive resiliency and minimizing the risk of both contact and non-contact injury.

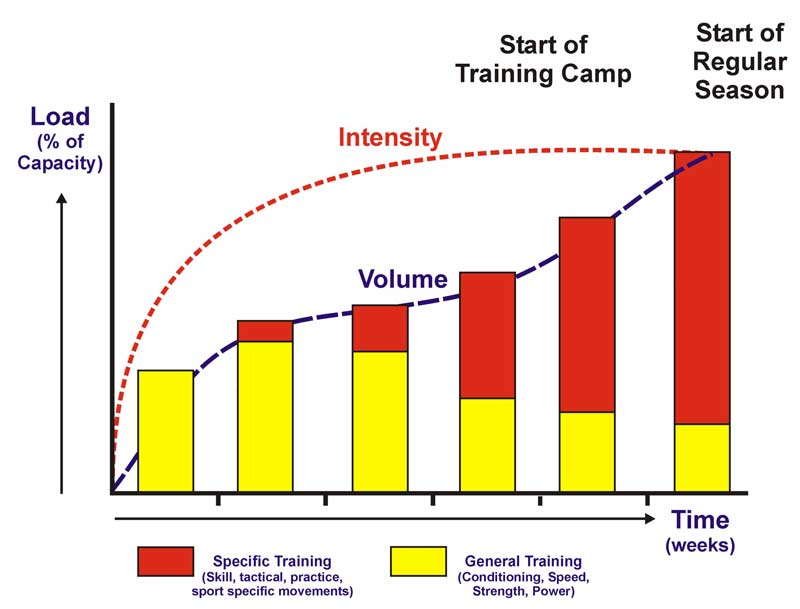

Similarly, Image 5 illustrates the distinction between the proportions of general work (i.e., sprinting, weightlifting, plyometrics, conditioning) and specific work (i.e., practice, skill work, tactical work, sport-specific agility, and movement patterns). General work predominates in the early stages of preparatory training, with specific work progressively growing in volume from week to week as athletes develop physical capacity and competence with both high- and low-intensity training elements. Once athletes fully return to competition, they must maintain a baseline of general work; the maintenance and further development of performance qualities will pay off in the long run.

Sprint training is exceptional for the high-intensity aspects of training while keeping the work general in nature, minimizing risk of injury. Share on XOnce again, sprint training is an exceptional means of addressing the high-intensity components of training while keeping the work relatively general in nature, minimizing the risk of injury during the preparatory phase. Over relatively short distances, an athlete can develop both lower and upper body strength, power, speed, and overall conditioning in a relatively short time. The problem with quickly resuming weight training is that many athletes will not have had access to weights during the layoff period, and muscle soreness will be a significant side effect of re-establishing conventional strength training approaches. The delays in returning to faster, more powerful movements created by the delayed onset muscle soreness (DOMS) will further restrict the rate of return to full sport and competition preparedness and readiness.

To allow sport coaches to understand the full importance of progressing gradually to specific elements, we must present this information in a practical way. There’s an inherent compulsion to rush back into every training element—both general and specific—as soon as possible to “hit the ground running” once competitions resume. However, most sports will re-enter playoff series or regular season competitions, and one game will not make or break a season. Playing the long game in this respect will pay more dividends for the individual players and the sport organizations as a whole. Live to fight another day is the mantra of civilizations across the planet. Sport teams should be no different.

Concluding Remarks

As with every aspect of the global pandemic, there is no blueprint for a successful return to normalcy. Sport organizations and performance directors must take a day-by-day approach using constant monitoring and ongoing communication. In many ways, the return-to-sport model will closely resemble the return-to-work models and the overall economic rebuilding of cities, states, provinces, and nations. Planned phases of recovery and reflection must be part of any return-to-sport approach. Rushing to be the first off the line is not a prudent means of managing the situation over the long run.

Planned phases of recovery & reflection must be part of any return-to-sport approach. Rushing to be the first off the line is not a winning strategy. Share on XSlow and steady may not be the answer either, but strategic, calculated, and deliberate will be the preferred approach by those with the patience and intelligence to lead their teams back to success. This is going to be the time when true leaders emerge in every sector of society, and true champions seize the moment with purposeful intent and precision. Perhaps the successful return of sports will be the truest indicator of our return to life as we once knew it.

Since you’re here…

…we have a small favor to ask. More people are reading SimpliFaster than ever, and each week we bring you compelling content from coaches, sport scientists, and physiotherapists who are devoted to building better athletes. Please take a moment to share the articles on social media, engage the authors with questions and comments below, and link to articles when appropriate if you have a blog or participate on forums of related topics. — SF