After his time as a collegiate and professional athlete, Nic Shimonek decided to pursue his true calling: performance coaching for elite athletes. Since beginning his career in Los Angeles, Nic’s desire to help individuals reach their highest potential has expanded beyond just elite athletes, and he now works with clients from all walks of life. His credentials include Certified Strength and Conditioning Specialist (CSCS) through the NSCA, Injury Resiliency and Performance Course through the Professional Football Strength and Conditioning Coaches Association (PFSCCA), Exercise Physiology at Stanford Center for Health Education (SCHE), Certification in Applied Functional Science (CAFS) from the Grey Institute, and functional range conditioning and assessment.

Freelap USA: You’re someone who has seemingly had a quick and unconventional development as a strength coach. For those who may not be familiar with you yet, what is your background and how do you see yourself gaining a strong foothold in this industry?

Nic Shimonek: I’m a former NFL quarterback, currently operating as a sports performance coach in Los Angeles, California. My time in the NFL was brief, but the impact it made on me was immense. From the relationships that were built to the opportunity to train at some of the best facilities around the country, it was an experience that has certainly provided value to my current career path.

Being a quarterback at the highest level requires an abundance of trust from your teammates. It’s up to YOU to communicate and lead by example in a way that creates instant buy-in. Very early on in my collegiate career, I tried to establish myself as the hardest worker in the room, and that reputation began to stick with me.

When deciding to retire from the NFL, I wanted to ensure that those communication channels and relationships stayed intact. Because of the reputation I built, I was extremely fortunate in having the ability to stay in contact with a lot of my college and professional teammates, as well as members of the strength and PT staffs, and I now work very closely with both. I train lots of old teammates and get lots of referrals for athletes in/visiting LA from previous staff members.

My experience as a professional athlete and the unique perspective I offer to sports performance allowed me to gain a foothold in this industry. I’ve lived it. I’ve breathed it, says @N_shim_9er. Share on XMy experience as a professional athlete and the unique perspective I offer to sports performance are what allowed me to gain a foothold in this industry. I’ve lived it. I’ve breathed it. I’ve been in the best facilities in the country and around world-class minds in this field as an athlete and now as a coach. While I’m still developing an elite coach’s eye and exhausting all of my resources to learn and grow as much as possible, my experiences and unique perspective on all things performance-related are what will set me apart.

Freelap USA: There are several advantages to being a former pro athlete as a strength coach but equally some disadvantages. Can you talk a little bit about how those advantages and disadvantages have played out for you so far?

Nic Shimonek: I think the number one advantage to being a professional athlete and then transitioning into this industry is the relationships that were built over the years. I’m still training athletes who I was direct teammates with and even athletes who are teammates of my former teammates. These clients have helped me build a foundation and trustworthy reputation to attract more athletes.

As for disadvantages, I think you alluded to it in the opening question. I’ve had a VERY quick and unconventional route to my current situation as a performance coach for some of the best athletes in their respective sports. The accelerated start to my career caused me to bypass very valuable moments that most people in this industry may go through.

For example, I’ve trained under and been around some of the best minds in the industry, but I never completed an internship (not yet anyway) or worked at a sports performance facility. Within four months of retiring from the league and starting my career, I started my own business and was on a world tour overseeing the health and wellness of a global rock star. It happened QUICK, but it was an opportunity that I couldn’t pass on! I had A LOT of downtime on tour (rock stars operate on a different sleep schedule than us regulars), which I filled with studying for the CSCS exam.

Completing the CSCS (and various other continuing education courses) while on tour gave me the confidence to begin reaching out and pursuing high-level athletes upon my arrival back in LA. One athlete turned into two, two turned into four, and so on. Here I am, three years later, having worked with over 40 professional athletes across the three major sports (NFL, MLB, NBA).

Freelap USA: Running your own business in such a big market like Los Angeles, what has been your early focus to establish your reputation and the growth of your business?

Nic Shimonek: It was intimidating at first because there are so many “performance coaches” in LA. Some already established, some trying to carve out a lane like me. The main thing I’ve done from the very beginning is to provide a service that GENUINELY cares for and wants to see the athletes succeed. Obviously, we all want our athletes to have success and do huge things on the field or court, but that’s where it stops for a lot of coaches. There isn’t a deeper connection with the client.

When I was training as an athlete, I wasn’t a huge name or highly touted guy, so I was just another body in a large group setting at these huge performance facilities: “Get in the back of the line and follow the guy in front of you.” I didn’t want my athletes to feel like that. I wanted the attention to detail for every individual rep to be felt and noticed.

I capped my first NFL off-season at five athletes. I probably could’ve had 8-10 guys had I really done some recruiting, but I wanted the quality of service to be so high with that first group of five that they were sure to tell their teammates where they had spent the last few months. I also wanted to establish a relationship with that first group that went beyond the training sessions, and to this day, any athlete I’ve worked with knows that I’m just a phone call (or text) away. Sure enough, those five turned into eight in the subsequent off-season. COVID-19 definitely had an effect on my operation, but the foundation had been set and it was only up from there, global pandemic or not.

Freelap USA: You’ve had an opportunity to work with a lot of high-profile athletes. Can you talk about some of the difficulties you’ve experienced with this? And what was your breakthrough moment, if there is one?

Nic Shimonek: I’m not sure if I’d consider it a difficulty but working around the preexisting schedule of a high-profile athlete has probably been the biggest challenge. The reason I wouldn’t call it a difficulty is because it’s all about your perspective and how you view the situation. You MUST be ADAPTABLE if you want to succeed in this world.

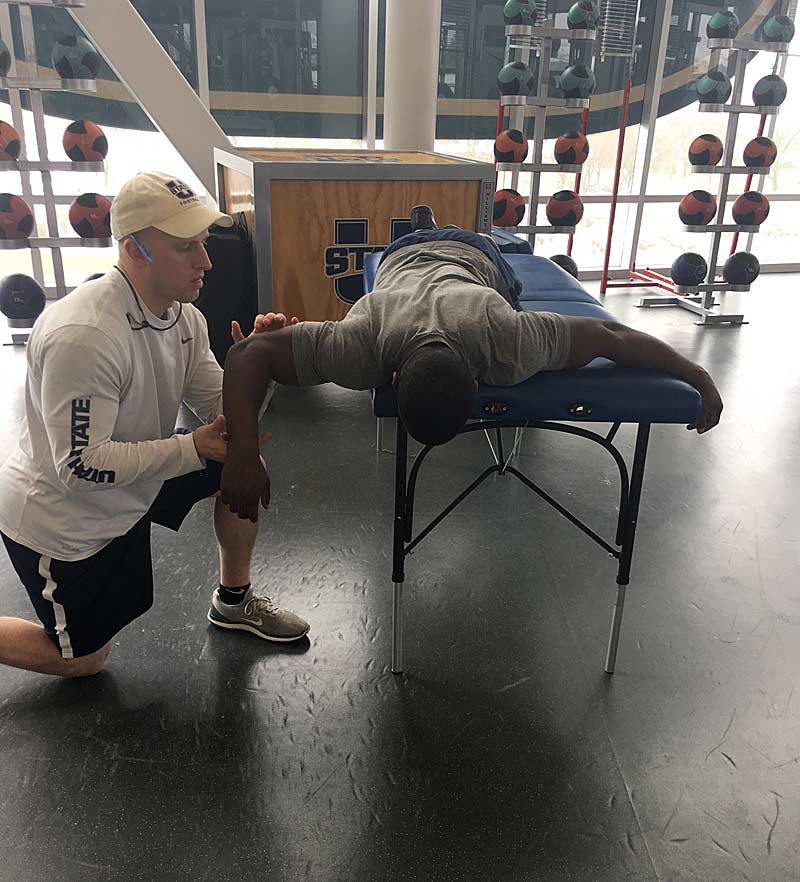

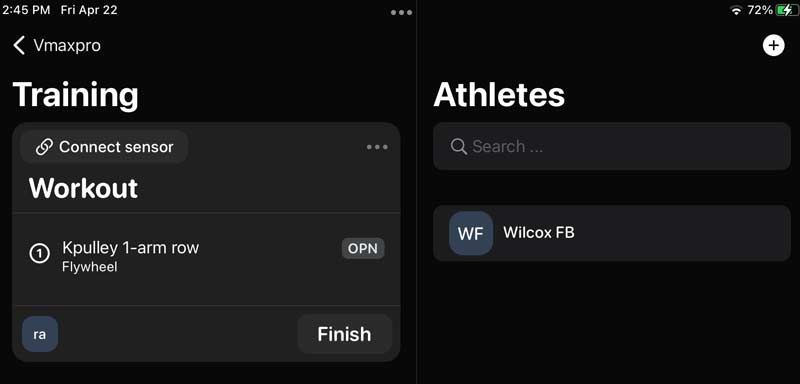

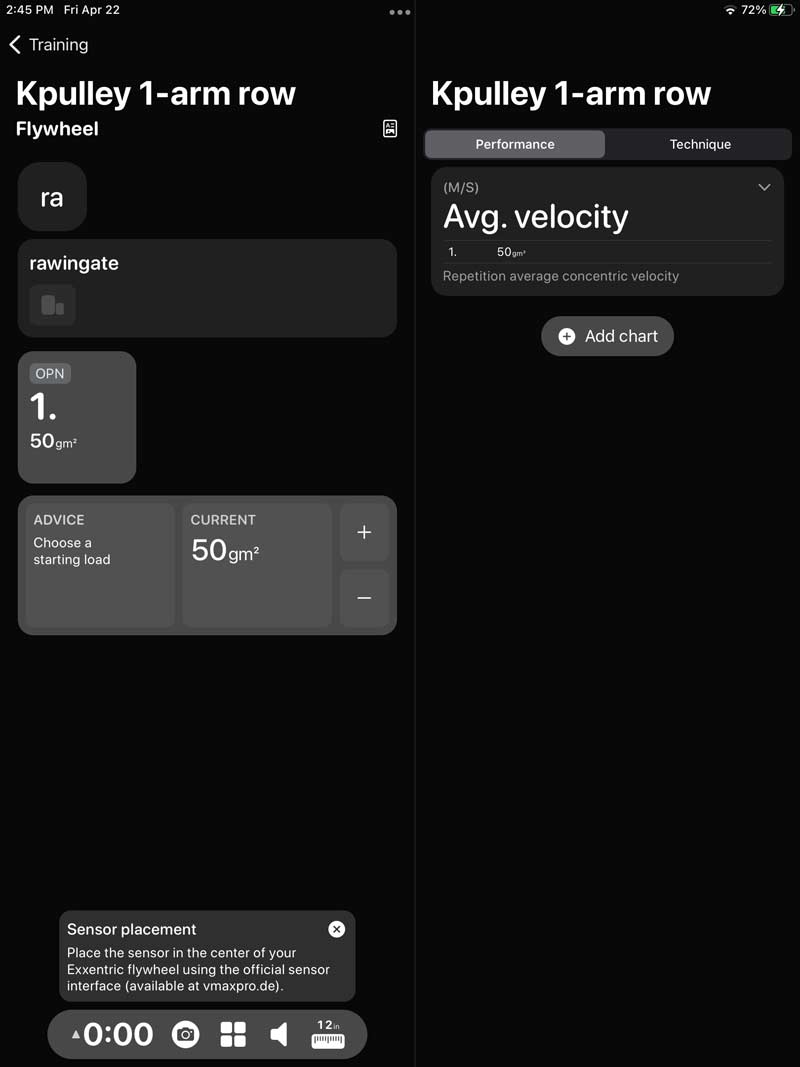

For example, I oversee all things performance-related for a running back in the NFL. I travel all over the country for him to ensure we’re putting him in a position to be successful. Throughout the off-season, he works with the organization’s physical therapy and S&C teams, his personal physical therapist, and a position-specific coach. It’s on me to digest all of this information and be in constant communication with the others he’s working with (current phase of training, current rehab protocols, volume of position work, etc.) and adapt/adjust my training plans to fill in the gaps.

I’m reluctant to consider any of this a ‘big break.’ That phrase implies that I got lucky to be in this position. In reality, I put the work in and built the relationships, says @N_shim_9er. Share on XI’m reluctant to consider any of this a “big break.” I feel as if that phrase implies that I got lucky to be in this position. In reality, I put the work in and built the relationships. I said what I wanted to accomplish out loud, and then made it happen. YOU control your destiny.

Don’t put a limit on what you can do or be in this field, or in any field for that matter. I’m constantly trying to learn, grow, and evolve as a coach and as a husband/father, regardless of the success early on in my career. Avoid a complacent mindset! Again, it’s about perspective and putting in the work to get where you want to be.

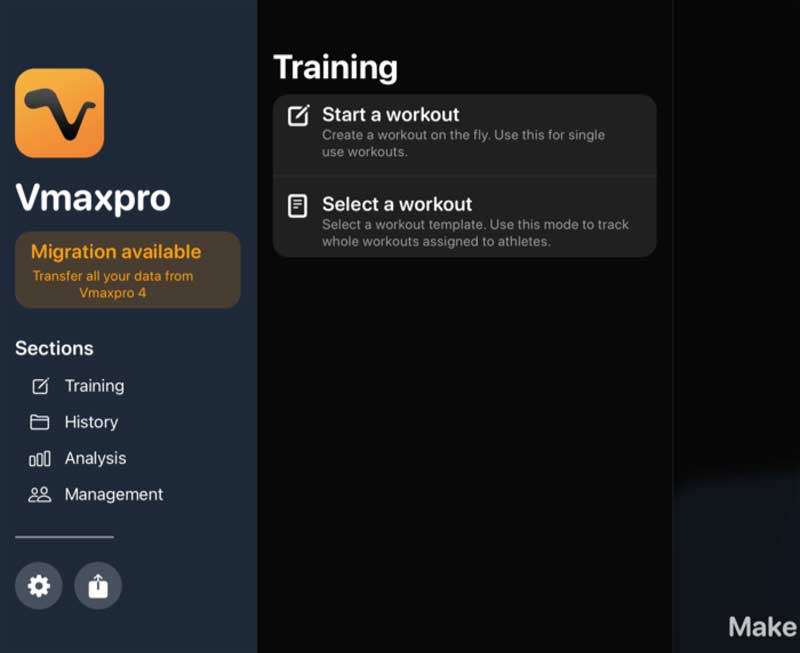

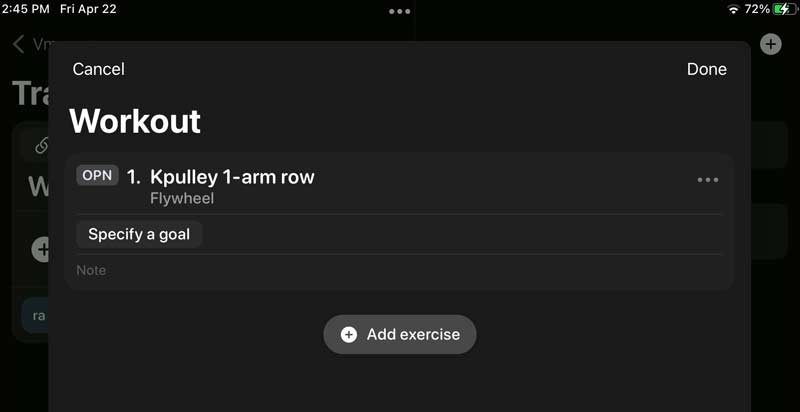

Freelap USA: You might have one of the coolest home gym setups in the entire country and have utilized your space very well. What are some of your favorite pieces of equipment and/or training applications to optimize a home gym space?

Nic Shimonek: I get asked all the time about my favorite piece of equipment in the gym. The Keiser machines are nice, and if I had unlimited space and budget, the Keiser Functional Trainer would be my number one machine because it’s so versatile. I also understand that’s not realistic for most “in-home” situations.

With that said, my go-to piece for home gyms would have to be a trap bar. With a TB, you can do strength and power work (deadlifts and loaded jumps), aerobic capacity work (carries/marches), upper body (overhead pressing or push-ups/rows), and everything in between. It’s just a matter of being creative and implementing the tool to achieve your desired outcome/adaptation. I like Kabuki’s trap bar because of the open face, but you can make it work with most trap bars on the market. It’s an awesome tool that will be a staple in my programming for a long time.

Lead photo by Carlos Herrera/Icon Sportswire.

Since you’re here…

…we have a small favor to ask. More people are reading SimpliFaster than ever, and each week we bring you compelling content from coaches, sport scientists, and physiotherapists who are devoted to building better athletes. Please take a moment to share the articles on social media, engage the authors with questions and comments below, and link to articles when appropriate if you have a blog or participate on forums of related topics. — SF

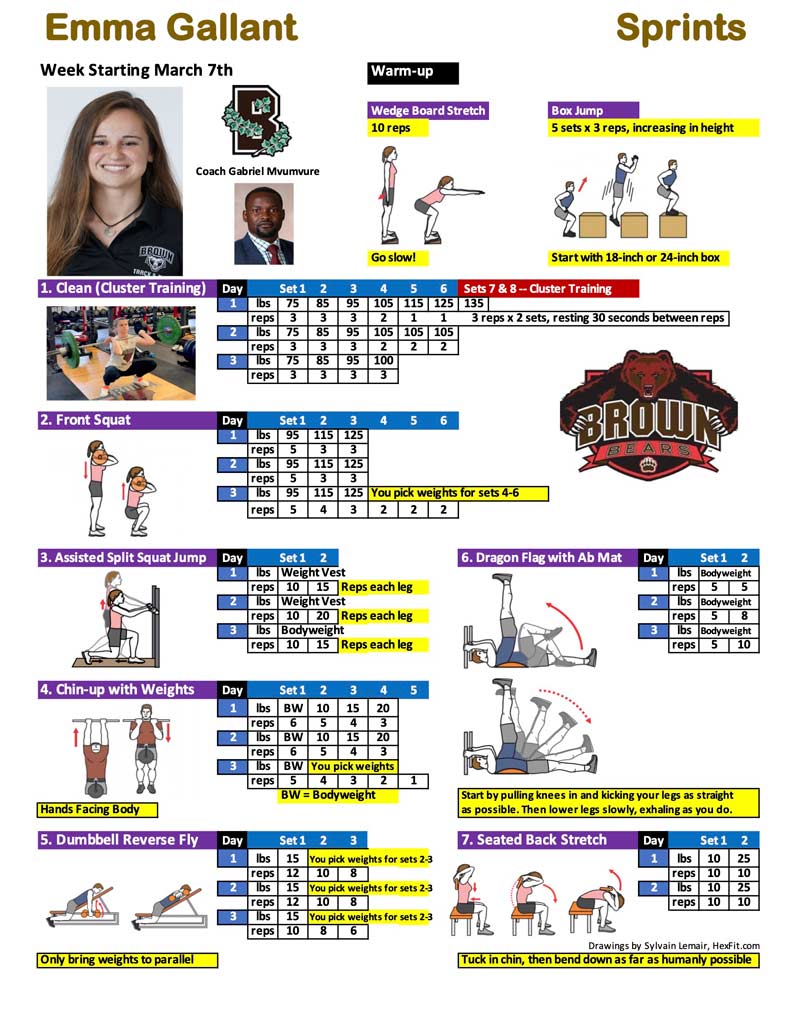

Kim Goss has a master’s degree in human movement and is a volunteer assistant track coach at Brown University. He is a former strength coach for the U.S. Air Force Academy and was an editor at Runner’s World Publications. Along with Paul Gagné, Goss is the co-author of Get Stronger, Not Bigger! This book examines the use of relative and elastic strength training methods to develop physical superiority for women. It is available through Amazon.com.

Kim Goss has a master’s degree in human movement and is a volunteer assistant track coach at Brown University. He is a former strength coach for the U.S. Air Force Academy and was an editor at Runner’s World Publications. Along with Paul Gagné, Goss is the co-author of Get Stronger, Not Bigger! This book examines the use of relative and elastic strength training methods to develop physical superiority for women. It is available through Amazon.com.