By Gabriel Mvumvure and Kim Goss

Athletic fitness magazines are packed with result-producing weight training methods promising to make you faster, stronger, and more powerful. Some are quite effective. Unfortunately, however, many are nearly impossible to implement with large groups—and with the popularity of weight training in high schools and colleges, pretty much all groups are large.

One workout system we’ve found to improve the quality of our workouts at Brown University is cluster training. Cluster training significantly increases the intensity of a workout by prolonging the rest time between repetitions. The good news is that it’s easy to administer and doesn’t require special equipment. The bad news is that it’s often prescribed incorrectly, leading to less-than-spectacular results.

Although cluster training is associated with weight training, forms of it can be found in other sports, such as the mile run.

A mile breaks down to 1,760 yards or 1,609 meters. The first official world record for the mile was 4:14.4, set by John Paul Jones on May 31, 1913. For many years, a sub-four-minute mile was considered by the coaching and scientific community to be unattainable. For example, in a paper published in 1935, respected track coach Brutus Hamilton wrote a piece called “The Ultimate of Human Effort.” Supporting his opinion with impressive tables and statistics, Hamilton predicted the fastest mile possible would be 4:01.66.

Ten years later, the record dropped to 4:01.4, slightly exceeding Hamilton’s prediction. Nine years later, on May 6, 1954, Roger Bannister of the United Kingdom proved all the skeptics wrong by crossing the finish line in 3:59.4.

Just a month after Bannister’s historic run, Australia’s John Landy ran 3:58, and the number of athletes who have broken the four-minute barrier since then is nearly 2,000. Bannister’s achievement thus became the go-to story for motivational speakers about overcoming mental and physical obstacles. Another story is how Bannister did it.

(Lead photo of Daniel Sarisky by Brian McWalters)

The Need…for Speed!

As neuroscientist Harold L. Klawans explained in Why Michael Couldn’t Hit, Bannister determined that the best way to approach his event was to run each quarter-mile as close as possible to one minute, so he asked the announcer to broadcast his splits and recruited pacers. During his record-breaking run, Bannister passed the three-quarter mark at exactly three minutes.

In Bannister’s era, many elite distance coaches believed it was necessary to develop an aerobic base before working on speed. Bannister thought differently. According to Klawans, Bannister focused on developing speed with 60-second quarter-miles, then he worked on improving his endurance to maintain that speed for four separate quarter-miles. Let’s break down Bannister’s approach with an exaggerated example.

An elite runner who has a goal of running a four-minute mile could start by running four quarter-miles in 60 seconds each but walking one minute between each rep. Thus, with their first workout, this athlete would run a four-minute mile…it just took them eight minutes to do it! When that workout becomes easy, their rest periods between reps would be decreased to 55 seconds, and so on, until that athlete develops the speed-endurance to run a four-minute mile!

Roger Bannister prolonged the rest time between quarter-miles, thus increasing each lap’s intensity. Therefore, by definition, he was performing cluster training. Share on XIn the years before Bannister’s historic run, no one could exceed the speed of four continuous, 60-second laps. However, Bannister could by prolonging the rest time between quarter-miles, thus increasing the intensity of each lap. Therefore, by definition, Bannister was performing cluster training.

So, what does Bannister’s approach to running the mile have to do with sprinter faster and lifting weights? Let’s start by expanding on the definition of intensity.

The Power of the Pause

Whereas training intensity on the track is measured by speed, training intensity in the weight room is defined by how much weight is lifted. Intensity has nothing to do with the difficulty of a set or how it, as Hans and Franz would say, “pumps…you up!”

If an athlete bench presses 200 pounds for one rep, the intensity is higher than if that same athlete grinds out 185 pounds for eight reps and bursts blood vessels in their nose. Yes, the eight-rep set may be more mentally challenging and create a high level of fatigue, but the intensity level is lower than the 200 pounds lifted for a single because it’s a lighter weight. Here’s where cluster training comes in.

Let’s say an athlete can bench press 190 pounds for three reps. By resting 15 seconds between reps, the athlete could load the bar to 195 pounds and might be able to complete three reps. Again, heavier weights = greater intensity.

In our first video, Brown sprinter Jaiden Stokes is shown performing six reps in the chin-up, resting 10 seconds between reps—that’s one cluster set. The rest period begins when Stokes’ feet touch the bench. Brown Head Sprint Coach Gabriel Mvumvure counts down backward between reps in this manner: 10, 9, 8…

Video 1. Cluster training for chin-ups.

To ensure the optimal stimulus is applied during each cluster, a training partner or coach should be recruited. A stopwatch is a nice addition, but most smartphones have a built-in timer. At Brown, a large clock is available near the platforms that athletes can use when flying solo. (And if you happen to play the piano and don’t mind annoying your teammates, bring your metronome to the gym to help you count.)

We used Stokes as an example for our video because many female athletes give up on chin-ups because it’s such a challenging exercise for them. By using cluster training, however, they can perform more reps than they could otherwise. However, our focus with chin-ups is on strength and not muscular endurance, so as soon as an athlete can complete at least six reps on their own, we start adding resistance with a special belt that holds weight plates.

Our focus with chin-ups is on strength, not muscular endurance, so as soon as an athletes can complete at least six reps on their own, we start adding resistance. Share on XFor example, Stokes has done 21 chin-ups non-stop, but during normal training, we keep her reps low and use resistance—as a result, she has done one rep with an additional 40 pounds. Stokes is not the exception. We’ve had several other female sprinters use this much weight or more, and several male sprinters use over 90 pounds of resistance. (At the end of the video, Brown sprinter Abayomi Lowe is shown performing a chin-up in strict form with 100 pounds.)

Sprinter Strength: It’s All Relative!

The origin of cluster training in the weight room is a bit of a mystery. About 50 years ago, bodybuilding icon Joe Weider popularized a form of inter-rep rest training for muscle building he called rest-pause. And in the 1940s, Body Culture magazine editor Henry J. Akins introduced the multi-poundage system, now known as drop sets. With drop sets, you perform a set to failure, reduce the weight, then perform additional sets with lighter weights. But that’s bodybuilding. For sprinters, we need to look at the work of the late Carl Miller.

Miller was the National Coaching Coordinator for USA Weightlifting and the head coach of the USA Weightlifting Team for the 1978 World Championships. In the ’70s, Miller made presentations at his training camps and wrote articles about using cluster training to improve the relative strength of a weightlifter.

Relative strength is the ratio of strength to body weight. If two people lift the same weight, the one who weighs less has greater relative strength. In a 2002 paper, sports scientist Igor Abramovsky warned that additional body weight for a weightlifter “…creates additional loading on the sportsman’s muscles because the weightlifter has to lift this excess weight during the execution of the weightlifting exercises; second, the sportsman’s speed deteriorates.” That speed also relates to sprinting.

Two ways a sprinter can run faster are by reducing the time they spend on the ground (ground contact time) and increasing the distance between each stride (stride length). Both can be achieved by becoming stronger. However, the sprinter wants to become stronger without increasing their body weight, even if that additional weight is muscle, because the extra weight will negatively affect their speed.

To prove our point, have a sprinter run 60 meters, then see how fast they run while wearing a 10-pound weight vest—even a 5-pound weight vest will make them run significantly slower. For longer distances, consider that extra body mass increases the stress on the cardiovascular system.

One advantage of cluster training over many other training systems is that no special setup is required. It’s not like supersets or tri-sets (i.e., performing multiple exercises in a circuit fashion), where several exercise stations often have to be reserved. Nor does it require special equipment such as chains, bands, or eccentric hooks. You simply manipulate the rest periods between the reps.

One advantage of cluster training over many other training systems is that no special setup is required. You simply manipulate the rest periods between the reps. Share on XNumerous scientific studies have proven the value of using longer rest periods between sets to increase strength and power; we’ve included several of them in our reference section. For example, one 2012 study published in the Journal of Strength and Conditioning looked at force, velocity, and peak power output using no rest between reps, 20 seconds’ rest, and 40 seconds’ rest. The exercise tested was the power clean.

The bottom line was that the 20-second-rest group was superior to the no-rest group, and the 40-second group was superior to the 20-second group. However, rather than discussing fascinating topics such as the desensitizing of Golgi tendon organs, let’s focus on the practical applications of cluster training.

Cluster Training Basics

Some coaches consider cluster training an advanced training method that should only be used by athletes with several years of experience and high strength levels. One reason for this belief is that Miller would prescribe as many as five sets of clusters with seven singles in each cluster, a protocol that is quite harsh and requires relatively lighter weights to be prescribed.

We use a different approach at Brown, believing that nearly all levels of athletes can perform cluster training. To get you started, here are seven guidelines we follow with our sprinters for cluster training:

- The length of the rest periods between reps is determined by the type of exercise. The more muscle mass involved in an exercise, and the more complex a movement, the more rest time needed. Whereas five seconds of rest between reps may be fine for chin-ups, you might need 30-45 seconds of rest between reps in the clean and push jerk to ensure optimal form.

- The number of clusters is determined by the conditioning of the athlete. You wouldn’t start an absolute beginner with five sets of clusters because they wouldn’t be able to recover. In contrast, an elite athlete might achieve their best results with five sets of clusters.

- The length of rest periods between clusters should be longer than with traditional sets. More rest is required between cluster sets. You wouldn’t perform max 60-meter sprints with 60-second rest intervals during a speed training workout, and likewise with cluster sets in the weight room. Whereas 2-3 minutes’ rest between sets may be fine for a conventional set of power cleans, 3-5 minutes’ rest may be necessary for cluster sets to maintain the highest intensity levels on subsequent sets.

- The weight used in each cluster is influenced by the total number of reps in each cluster and the total number of clusters. For Miller’s hardest workouts, the percentages for snatches were 80-85% of 1-repetition maximum, and for clean and jerks, 77-82%. However, higher percentages can be used if fewer reps are performed in each cluster and fewer clusters are performed.

- Use conventional sets to warm up for clusters. Perform enough sets with conventional sets to get you near a max effort, then proceed with cluster training. For example, if you were to perform a cluster set using 200 pounds in an exercise (say, a deadlift), you might warm up as follows: 105 x 5, 135 x 4, 155 x 3, 175 x 2, and 190 x 1. Performing cluster sets for every warm-up set would create too much fatigue, reducing the amount of weight that could be used on the primary work sets.

- Limit cluster training to one exercise per workout. Cluster training is especially taxing on the nervous system, and the quality of your workout would suffer if you tried to use it with several exercises in the same workout. An exception would be if the second exercise was for an upper-body exercise, such as chin-ups.

- Make the first exercise the cluster set exercise. You want to use the heaviest weights in cluster sets, so clusters should be performed first in your workout when you are fresh. The exception is with smaller group exercises. For example, if using cluster sets on chin-ups, we would perform them after our major power and leg exercises, such as cleans and squats.

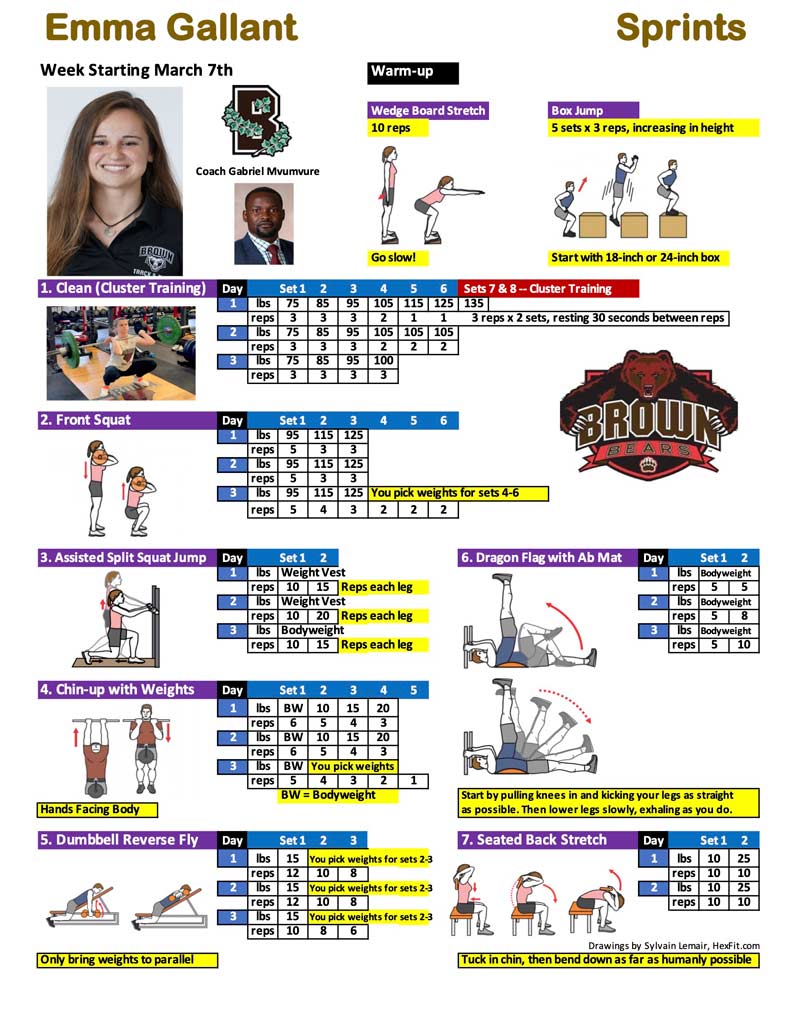

Pulling this together, Figure 1 shows an example of a workout with Brown sprinter Emma Gallant during her introduction to cluster training. Cluster training is performed during the last two sets of the first exercise, which is full cleans.

From the Blackboard to the Lifting Platform

One key to success in cluster training with beginners is to start conservatively, using longer rest periods and just one set. The following are examples of cluster training progressions in various exercises. For these progressions, the rest periods between sets are 3-5 minutes. Note that the rest periods decrease in the second variations, allowing the athlete to get accustomed to this type of training.

One key to success in cluster training with beginners is to start conservatively, using longer rest periods with just one set. Share on X-

Chin-Ups

1 set x (3 reps, 3 reps) x 10 seconds’ rest between reps

2 sets x (3, 3, 3) x 5 seconds’ rest

3 sets x (3, 3, 3, 3) x 5 seconds’ rest

-

Power Clean

1 set x (2, 2) x 30 seconds’ rest

2 sets x (2, 2) x 20 seconds’ rest

3 sets x (2, 2, 2) x 20 seconds’ rest

-

Clean and Push Jerk

1 set x (1, 1) x 45 seconds’ rest

2 x sets (1, 1) x 30 seconds’ rest

3 x sets (1, 1, 1) x 30 seconds’ rest

One way to determine when an athlete is ready for more training volume (total reps x sets) in cluster training is by measuring barbell speed. For sprinters, you have to be careful not to let fatigue reduce bar speed to ensure optimal transfer to their sport. For more on this topic, see our article “Using Fast Eccentric Squats to Sprint Faster and Jump Higher.”

Bar speed can be measured using a velocity-based training (VBT) device to determine what’s known as the critical drop-off point. Such a device is shown by hurdler Brooke Ury squatting in the second video. Ury’s lift is followed by a conventional squat performed by Maddie Frey, a sprinter who this year broke the 32-year-old school record in the 200m.

Video 2. Velocity-based training with squats.

The critical drop-off point—a term attributed to the late track coach Charles Francis—occurs when the quality of an exercise degrades to the point where the muscle fibers being targeted are no longer being stimulated. For bodybuilding, the late strength coach Charles R. Poliquin said the critical drop-off point occurs with 20% diminishing returns. For relative strength training, he said the range is 5-7%. Let’s look at an example of how this approach works.

Let’s say a sprinter is performing barbell back squats, and the cluster training protocol is 3 x (1, 1, 1) x 30 seconds’ rest, with 4 minutes’ rest between sets. If the barbell speed during the ascent portion of the squats during the second cluster does not decrease by more than 7%, the athlete should perform the third set. However, if the bar speed decreases by more than 7%, the athlete should not perform the third set. This decrease in bar speed could also suggest that this athlete may be better off going back to conventional training until their conditioning level improves.

In our third video, Stokes (who has cleaned 165 pounds) cleans four reps with 20 seconds between reps. Note that rather than counting down every second in a rest period (which can be quite annoying), Coach Mvumvure waits until 10 seconds remain before counting down. If 30 seconds of rest were prescribed, he would note when 10 seconds have passed, then count down from 10.

Video 3. Cluster training for cleans.

For a sprinter, it’s important to select exercises for cluster training that give these athletes the most “bang for their buck.” Weightlifting movements (snatches, cleans, jerks, and so on….) are the number one choice. Powerful leg exercises such as front squats (a Brown favorite!) and deadlifts are also good choices. Poor choices would be bicep curls or any isolation movement designed to “pump…you up!”

For a sprinter, it’s important to select exercises for cluster training that give these athletes the most ‘bang for their buck.’ Share on XSprinting is a fast-twitch activity requiring the performance of high-intensity workouts, both on the track and in the weight room. Roger Bannister inspired us with his historic mile run and revolutionary training methods, so take advantage of his pioneering work and incorporate cluster training into your workouts!

Since you’re here…

…we have a small favor to ask. More people are reading SimpliFaster than ever, and each week we bring you compelling content from coaches, sport scientists, and physiotherapists who are devoted to building better athletes. Please take a moment to share the articles on social media, engage the authors with questions and comments below, and link to articles when appropriate if you have a blog or participate on forums of related topics. — SF

Kim Goss has a master’s degree in human movement and is a volunteer assistant track coach at Brown University. He is a former strength coach for the U.S. Air Force Academy and was an editor at Runner’s World Publications. Along with Paul Gagné, Goss is the co-author of Get Stronger, Not Bigger! This book examines the use of relative and elastic strength training methods to develop physical superiority for women. It is available through Amazon.com.

Kim Goss has a master’s degree in human movement and is a volunteer assistant track coach at Brown University. He is a former strength coach for the U.S. Air Force Academy and was an editor at Runner’s World Publications. Along with Paul Gagné, Goss is the co-author of Get Stronger, Not Bigger! This book examines the use of relative and elastic strength training methods to develop physical superiority for women. It is available through Amazon.com.

References

Abramovsky, I. “A weightlifter’s excess bodyweight and sport results,” Olimp magazine, 1:28-29:2002. Translated by Andrew Charniga, www.sportivnypress.com.

Baack, LJ, ed. “The Sport of Track and Field: Flights of Fancy,” Chapter 4 in The Worlds of Brutus Hamilton, Tafnews Press, 1975.

García-Ramos, A., Padial. P., Haff, G.G., et al. “Effect of Different Interrepetition Rest Periods on Barbell Velocity Loss During the Ballistic Bench Press Exercise.” The Journal of Strength and Conditioning Research. 2015;29(9):2388–2396.

Hamilton, Brutus. “The Ultimate of Human Effort,” 1935.

Hardee, J.P., Triplett, N.T., Utter, A.C., Zwetsloot, K.A., and McBride, J.M. “Effect of interrepetition rest on power output in the power clean.” The Journal of Strength and Conditioning Research. 2012;26(4):883–889.

Klawans, Harold L. Why Michael Couldn’t Hit: And Other Tales of the Neurology of Sports. W H Freeman & Co., Sep 1, 1996, p. 203–214.

Miller, Carl. The Sport of Olympic-Style Weightlifting, Training for the Connoisseur. Sunstone Press, Apr 10, 2011, p. 87–90.

Oliver, J.M., Jagim, A.R., Sanchez, A.C., et al. “Greater gains in strength and power with intraset rest intervals in hypertrophic training.” The Journal of Strength and Conditioning Research. 2013;27(11):3116–3131.

Prestes, J., Tibana, R.A., da Cunha Nascimento, D., et al. “Strength and Muscular Adaptations Following 6 Weeks of Rest-Pause Versus Traditional Multiple-Sets Resistance Training on Trained Subjects.” The Journal of Strength and Conditioning Research, 2017;33(suppl. 1).

Schoenfeld, B.J., Pope, Z.K., Benik, F.M., et al. “Longer Interset Rest Periods Enhance Muscle Strength and Hypertrophy in Resistance-Trained Men.” The Journal of Strength and Conditioning Research. 2016;30(7):1805–1812.