By Gabriel Mvumvure and Kim Goss

For more than a half-century, the back squat has been the go-to exercise for building bigger and stronger athletes. It’s become so popular, many strength coaches stand by the motto: “If you don’t have the back squat in your program, you don’t have a program!” However, many strength coaches have also ditched the back squat in favor of front squats in recent years. So, let’s take a deep dive into the benefits of this squat variation and particularly how it applies to sprinters.

Whereas there’s no question that discus throwers and shot putters have benefited from all forms of squats, some sprint coaches see little value in these exercises. These outliers believe that strength developed in the weight room will not transfer to the power needed to sprint faster and it will slow athletes down by adding bulky muscles. These opinions are based on misinformation. Just as strength coaches don’t prescribe 5-mile jogs for their athletes, sprint coaches shouldn’t have their athletes lift like Arnold Schwarzenegger!

(Lead photo by Viviana Podhaiski, LiftingLife.com.)

Next question: “Why full squats for sprinters?” If the legs do not bend past 90 degrees in sprints, why perform any leg exercise through a full range of motion? Two reasons:

- There are three ways to go in the squat: above parallel, parallel, and below parallel (i.e., quarter squats, parallel squats, and full squats). One problem with quarter squats is that athletes can use considerably more weight than with the other two squat depths, placing excessive stress on the spine. Such stress, and the subsequent lower back pain it produced, motivated Russian sports scientist Yuri Verkhoshansky to develop classical plyometric exercises such as depth jumps.

- Parallel squats use less weight than quarter squats but place the highest levels of shear forces on the knees (see reason #4 below). Consider that knee injuries are rare in weightlifting, and you would be hard-pressed to find examples of athletes tearing an ACL from a full squat. Additionally, limiting the range of motion of squats poses the risk of reducing flexibility and inhibiting the protective functions of the fascia (as discussed in our article on fast eccentric squats).

- Squatting enables sprinters to keep sprinting and jumpers to keep jumping. To achieve the highest levels of performance, some high school track and field coaches believe it’s best for their athletes to compete in indoor track, outdoor track, and even joint summer sprint programs. Maybe that’s not such a good idea?

- A 2017 study on high school athletes found that those who focused on just one sport had an 85% higher incidence of lower-extremity injury. As it relates to track and field, a 1987 study tracked 17 high school track teams (174 males, 83 females) over 77 days. The authors concluded: “A total of 41 injuries was observed over this period of time. One injury occurred for every 5.8 males and every 7.5 females. On the average, an injury resulted in 8.1 days of missed practice, 8.7 days for males and 6.6 days for females. Sprinting events were responsible for 46% of all injuries.” Ouch!

Yes, we understand sprinters “feel the need…the need for speed,” but injuries are a red light to finish-line glory. Resistance training is a green light.

In a meta-analysis of 25 research studies involving 3,464 athletes, researchers found that strength training cut overuse injuries in half and all injuries by one-third! Further, approximately 70% of ankle and knee injuries are non-contact—the athletes were not touched! One explanation for the high rate of non-contact injuries is that sports-specific training may compromise the elastic qualities of connective tissues, making these tissues act like frayed rubber bands, ready to snap.

Now that we have your attention, let’s explore how sprinters can benefit from front squats.

Front Squats: A Question of Balance

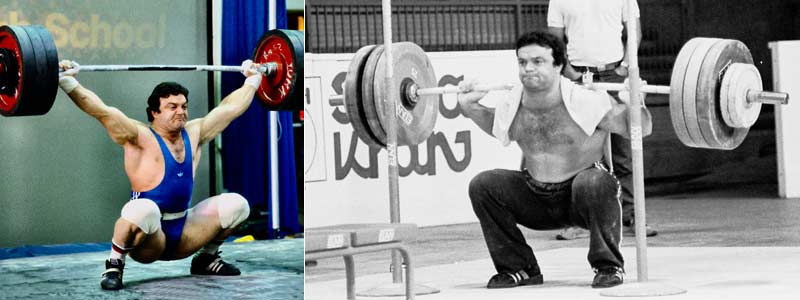

In weightlifting, many coaches of Olympic champions and world record holders favor the front squat over the back squat. During their “high impact” weeks, elite weightlifters from Kazakhstan trained six days a week and performed eight training sessions a day (yes, eight sessions a day!). They squatted twice a day, with 10 of those workouts being front squats and two being back squats. Bulgarian weightlifting coach Ivan Abadjiev shared a similar mindset.

Abadjiev’s athletes won a dozen Olympic gold medals and shocked the world in 1972 when their team beat the mighty Russians. Abadjiev “changed the game” by focusing on only a few lifts, in contrast to the Russians, who performed a large variety of exercises.

In his early years as the national coach, Abadjiev often had his lifters squat twice a day for a total of 12 training sessions in a week; nine of those workouts were front squats and only three were back squats. Eventually, Abadjiev determined that the only supplemental leg exercise needed for his elite athletes was the front squat. But that’s weightlifting—what do elite strength coaches think of the front squat?

According to legendary strength coach Charles Poliquin, European coaches were asked if their athletes could only perform three exercises, what would they choose? The consensus was the power snatch, the incline bench press, and the front squat. With that background, here are a dozen reasons why front squats hold an edge over back squats for all athletes, particularly sprinters:

Here are a dozen reasons why front squats hold an edge over back squats for all athletes, particularly sprinters. Share on X1. Emphasizes the Lower Portion of the Hamstrings

Some strength coaches contend that low-bar, wide-stance powerlifting back squats work the hamstrings more effectively than conventional back squats. Yes and no…and it’s a big NO for sprinters, according to Canadian strength coach and posturologist Paul Gagné.

“The powerlifting back squat focuses on the proximal section of the hamstrings, closer to the glutes,” says Gagné. “I’ve seen many NFL players with big glutes and large upper thighs but little development in the muscles around the knee—they are basically built like horses. Such unbalanced development may be one reason the NFL has such a high risk of hamstring injuries.”

Gagné says balance during the front squat is influenced by the relationship between the center of gravity of the bar and the center of gravity of the body, a concept presented by Russian sports scientist Robert Roman in 1986. “With the back squat, the bar stays over the body’s center of gravity. With the front squat, the bar is forward of the body’s center of gravity. For an athlete to maintain their balance during the lift, the distal portion of the hamstrings, closer to the knee, will be more active than during the back squat. I believe that such development is one reason weightlifters seldom get hamstring injuries.”

2. Transfers Better to Sprint Starts

Explosive strength is the ability to overcome inertia, such as during the start of a 100-meter sprint. In our article about fast eccentric squats, we discussed how relatively weak hamstrings (in relation to the quadriceps) could affect explosive strength.

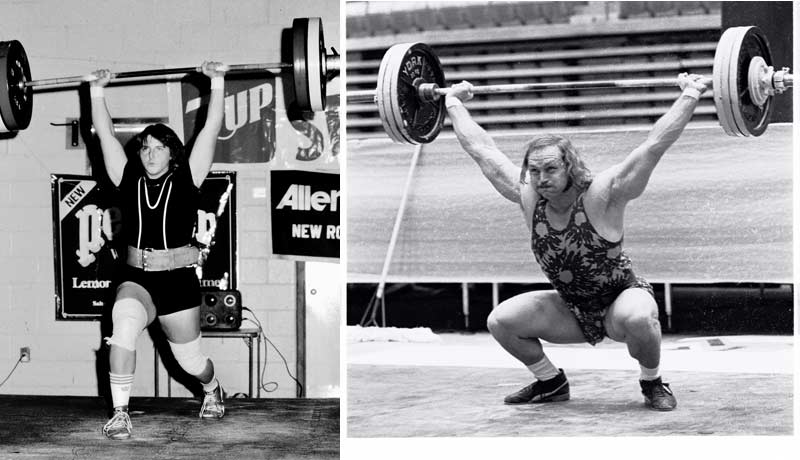

It can be argued that weightlifters perform back squats, but they also perform front squats, and the catch position and recovery from the clean resembles a front squat. Research on college football players found that weightlifters exceeded powerlifters in short sprint speed, suggesting that front squats more effectively train the start. One extreme example is the mock race between Mark Cameron and Renaldo Nehemiah.

Research on college football players found that weightlifters exceeded powerlifters in short sprint speed, suggesting that front squats more effectively train the start. Share on XCameron was the second American to clean and jerk 500 pounds, which he did at 240 pounds body weight in 1980. Renaldo Nehemiah ran the 100-meter hurdles in under 13 seconds, the first to do so, and played wide receiver for the San Francisco 49ers. In a mock race at the University of Maryland, Cameron was ahead of Nehemiah for the first 10 yards, at which point Nehemiah rocketed ahead.

Another point is that the start of a sprint is highly influenced by the strength of the calves. A 2007 study concluded that the gastrocnemius medialis “is one of the most important muscles generating the start and block acceleration.” In squats, a narrower foot placement and full range of motion increases the activity of these muscles. Athletes tend to front squat with a narrower stance than when they back squat, especially if they perform the wider-stance low-bar squats promoted by many prominent powerlifters and strength coaches. This calf-strengthening effect may help prevent hamstring injuries. In a study spanning 17 years, researchers found that one of the greatest risk factors for a hamstring injury was a previous ankle injury to that same leg.

3. More Specific to Upright Sprinting Mechanics

Sprinters don’t run on their heels. Because the barbell is forward of the body’s center of gravity during the front squat, the resistance is felt more on the forefoot. Also, the upright sprint position more resembles a front squat than a back squat.

Another characteristic of the front squat is that it requires more dorsiflexion than a back squat. One of the issues we’ve found with incoming sprinters is they often lack ankle mobility and the strength to maintain dorsiflexion when they sprint. As such, we have these athletes perform remedial strength exercises and special sprint drills to achieve and maintain optimal sprint mechanics during a race.

4. Superior to Back Squats for Improving Knee Stability

Although the word “quad” is in quadriceps, there are six quadriceps muscles. Research has shown the vastus medialis muscles, located on the medial (inside) portion of the knee, are more active with front squats than back squats. This is because the trunk is more upright, and the knees travel more forward than the back squat.

Gagné says that training the vastus medialis muscles is critical for maintaining optimal knee stability while sprinting, especially the lower portion called the vastus medialis oblique. As such, it’s important to emphasize exercises that strongly solicit the vastus medialis muscles, such as the front squat. And, according to Poliquin, the key to strengthening the vastus medialis muscles is performing full “knees in front of the toes” squats.

In his work with elite athletes, Poliquin found that getting athletes to perform full-range squats enabled them to reduce their risk of injury. For example, when he was hired to work with Canada’s national ski team, he said every athlete who had been with the team for the previous five years needed knee surgery. For the following five years under this legendary strength coach’s watch, no skiers went under the knife. Likewise, when he took over the training of the Canadian national women’s volleyball team, all but one athlete had jumper’s knee (a form of tendinitis). Within two months, only one athlete had knee issues.

As for the stress on the knees with both squat variations, there are two types of forces to be concerned about with squats: compressive and shear. Compressive forces act vertically on the knee, trying to compress the knee. Shear forces act horizontally on the knee, trying to pry the knee joint apart.

Front squats and back squats place equal amounts of shear force on the knee, but front squats place less compressive force….it makes sense that sprinters should focus more on the front squat. Share on XAccording to Dr. Aaron Horschig, founder of Squat University, there is an inverse relationship between compressive force and shear force during squats. Thus, the deeper the athlete squats, the higher the compressive force and the lower the shear force. Front squats and back squats place equal amounts of shear force on the knee, but front squats place less compressive force. Sprinting is stressful enough on the knees (as suggested by the study previously mentioned), so it makes sense that sprinters should focus more on the front squat.

5. Works the Glutes More Effectively Than Wide-Stance Back Squats

If a sprinter’s glutes are relatively weak, their hamstrings must work harder, potentially increasing the risk of hamstring injuries. Some powerlifting coaches say that a low-bar, wide-stance back squat more effectively works the glutes, but there is a positive relationship between squat depth and the work of the largest glute muscle, the gluteus maximus. The range of motion is restricted with the modern powerlifting squat as the wider stance transfers much of the work to the adductors.

6. Accesses and Improves Flexibility

If you’re looking for a quick test to determine an athlete’s flexibility, the front squat is hard to beat, and not just for the lower body. For example, athletes who have tightness in their forearms and the muscles that externally rotate the shoulders will have difficulty supporting the bar on their clavicles. This doesn’t mean they will never be able to front squat.

Those athletes who cannot comfortably perform the front squat can attach lifting straps to the bar to reduce the stress on their wrists and forearms, and athletes can hold the bar on their fingertips with a thumbless grip. As athletes perform these variations, they should eventually be able to switch to the conventional front squat technique. Yes, there is a front squat variation where the arms are crossed in front, but this does little to improve flexibility, especially in the upper body.

Many YouTube videos show how to improve flexibility to perform front squats properly. Most of these ideas are effective, but one of the fastest ways to improve flexibility for the front squat is to perform front squats!

7. May Access Strength Imbalances

The hamstring/quad strength ratio has been extensively studied in athletes and the general population. Sports scientist Bud Charniga has some strong opinions about using seated exercise machines to test this ratio:

“All too often, athletes are tested and even trained seated on machines to measure, as well as to train hamstring to quadriceps strength, i.e., balance between thigh flexion to extension strength. This practice persists, utilizing in many cases expensive machinery; even though athletes in dynamic sport, with few exceptions; perform standing. Furthermore, it is unclear how training hamstring muscles lying face down or seated will have some prophylaxis effect for athletes running about on a field or court; where flexing and straightening of lower extremities entails far more complexity. After all, how often does one see an athlete sustain a hamstring injury lying face-down; or for that matter, seated?”

As an alternative, one interesting idea presented by Poliquin was that strength imbalances between the quadriceps and hamstrings could be determined by comparing the 1-repetition maxes of the front and back squat. According to Poliquin, if your front squat max does not equal 85% of your back squat, your hamstrings are relatively weak. Although this is just Coach Poliquin’s observations (and his formula may not be accurate), he does have a remarkable track record of reducing the risk of knee injuries in elite skiers and other athletes.

8. Improves Posture

According to Gagné, the front squat involves more body awareness than the back squat. “If you were to try squatting with a blindfold, it would be much more challenging to maintain your balance with a front squat rather than a back squat.”

Relating back to Roman’s drawing, Gagné believes that the reduced stability of the front squat may provide an advantage in sprinting. He says the base of support, the forefoot, is relatively small in sprinting. Because the foot strike is performed at high speeds, and the athlete has to deal with the disruptive forces of turns (and in the case of hurdles, jumps), the front squat may enable the athlete to more easily sprint with optimal technique and apply more force into the ground.

9. Strengthens the Upper Back Muscles Used in Sprinting

To keep the bar on the chest during the front squat, Gagné says many upper body muscles (and the abdominals) must be strongly engaged, especially the rhomboids and infraspinatus. The rhomboids help pull the shoulders back, which is important since sprinters with weakness in these muscles can develop a round-shouldered posture that affects sprinting mechanics. These muscles, which help athletes maintain optimal posture in the upright sprint position, are less active during a back squat.

The rhomboids, which help athletes maintain optimal posture in the upright sprint position, are less active during a back squat than during the front squat. Share on XIt’s been said that acceleration begins with the upper body, so upper body strength is important. Look at many of the best short sprinters, and you’ll find that they often have exceptional upper body development. Likewise with good running backs in football.

10. A Spotter May Not Be Required

For an athlete to safely back squat, they should lift in a power rack with the safety supports set at the appropriate height to catch the bar. Back and side spotters should also be recruited. Unfortunately, such guidelines are seldom followed in the real world. And if spotters are available, they are often inattentive or stand too far away from the athlete to save failed lifts.

With a front squat, experienced lifters can squat outside the rack. If the weight is too heavy or they get out of position, they can easily dump the bar forward. However, with this approach, bumper plates should be used (to protect the bar and the floor), and the lift should be performed on a platform (to avoid damaging the floor).

[vimeo 686018025 w=800]

Video 1. The safest way to perform squats is inside a power rack. However, experienced lifters can perform front squats outside a rack, as the athlete can easily dump the bar forward. Shown is senior sprinter Maddie Frey, who in four months improved her vertical jump (no step) from 26.6 inches to 29.4, and freshman sprinter Andrew Li, who improved his vertical jump (no step) from 37.3 to 39.9 in one month. (Frey action photo by Leslie Whiting-Poitras; Li action photo courtesy David Silverman, Brown University Athletic Communications)

11. More Specific to the Start of the Clean

Because the trunk is more upright than in the back squat, the starting position of a front squat more closely approximates the start position of a clean or power clean. According to some Russian researchers, the back squat would be considered more specific to the snatch, as the wider grip forces the athlete to start with a back angle more parallel to the floor. Again, many elite weightlifting coaches believe the front squat is more important than the back squat for improving weightlifting ability.

12. Discourages Cheating

With back squats, athletes are more likely to cheat themselves by performing a partial lift. With front squats, according to Poliquin, athletes are more likely to squat lower. If athletes get out of position, such as by shooting their hips up or rounding their upper back, they will often drop the bar.

Big Benefits for Sprinters

Countless track and field athletes have benefited from performing back squats at the exclusion of front squats, and there is no question that back squats are valuable, especially when performed through a full range of motion. That said, we believe we’ve made a strong case as to why the front squat might be better than the back squat for sprinters, especially when compared to wide-stance powerlifting squats.

Is the back squat still “the king” of exercises? Absolutely, but for sprinters, the front squat should be a primary exercise in their weight training toolbox.

Since you’re here…

…we have a small favor to ask. More people are reading SimpliFaster than ever, and each week we bring you compelling content from coaches, sport scientists, and physiotherapists who are devoted to building better athletes. Please take a moment to share the articles on social media, engage the authors with questions and comments below, and link to articles when appropriate if you have a blog or participate on forums of related topics. — SF

Kim Goss has a master’s degree in human movement and is a volunteer assistant track coach at Brown University. He is a former strength coach for the U.S. Air Force Academy and was an editor at Runner’s World Publications. Along with Paul Gagné, Goss is the co-author of Get Stronger, Not Bigger! This book examines the use of relative and elastic strength training methods to develop physical superiority for women. It is available through Amazon.com.

Kim Goss has a master’s degree in human movement and is a volunteer assistant track coach at Brown University. He is a former strength coach for the U.S. Air Force Academy and was an editor at Runner’s World Publications. Along with Paul Gagné, Goss is the co-author of Get Stronger, Not Bigger! This book examines the use of relative and elastic strength training methods to develop physical superiority for women. It is available through Amazon.com.

References

American Orthopaedic Society for Sports Medicine. “Sports specialization may lead to more lower extremity injuries.” ScienceDaily. 7/23/17.

Brenner, J.S. and the Council on Sports Medicine and Fitness. “Sports Specialization and Intensive Training in Young Athletes.” Pediatrics. 2016;138(3):e20162148.

Coh, M., Peharec, S., and Baãiç, P. “The sprint start: Biomechanical analysis of kinematic, dynamic and electromyographic parameters.” New Studies in Athletics. 2007;22(3):29–38.

Escamilla, R.F. “Knee biomechanics of the dynamic squat exercise.” Medicine & Science in Sports & Exercise. 2001;33(1):127–141.

Goss, K. Ivan Abadjiev personal communication. 5/23/11.

Goss, K. Naim Süleymanoğlu personal communication. 1988.

Gullett, J.C., Tillman, M.D., Gutierrez, G.M., and Chow, J.W. “A Biomechanical Comparison of Back and Front Squats in Healthy Trained Individuals.” The Journal of Strength and Conditioning Research. 2009;(23)1:284–292.

Hennessey, L. and Watson, A.W. “Flexibility and posture assessment in relation to hamstring injury.” British Journal of Sports Medicine. 1993;27(4):243–246.

Horschig, A., Sonthana, K., and Neff, T. The Squat Bible, pp. 97–100. Squat University LLC, 2017

Krychev, A. “The Bulgarian weightlifting program (according to Alex Krychev), uploaded December 2019, iduc.pub

Komi, P., ed. “Training for Weightlifting,” Strength and Power in Sports, pp. 365-366, Blackwell Scientific Publications, 1992.

Lauersen, J.B., Bertelsen, D.M., and Andersen, L.B. “The effectiveness of exercise interventions to prevent sports injuries: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomised controlled trials.” British Journal of Sports Medicine. 2014;48(11):871–877.

Rojas, I. and Sisto, G.. Kazakhstan Weightlifting System for Elite Athletes. BookCrafters. 2015.

Roman, R.A. The Training of the Weightlifter, pp. 18, Sportivny Press, 1986

Watson, M.D. and DiMartino, P.P. “Incidence of injuries in high school track and field athletes and its relation to performance ability.” American Journal of Sports Medicine. 1987;15(3):251–254.

Yavuz H.U., Erdag, D., Amca, A.M., and Aritan, S. “Kinematic and EMG activities during front and back squat variations in maximum loads.” Journal of Sports Sciences. 2015;33(10):1058–1066.