Break out the smelling salts, crank up the Lil Boosie, tighten up the lifting belt—time to smash a big squat. The team surrounds the athlete, chanting encouragement as the spotters set up. The athlete takes the bar out, and there is a feeling of excitement and almost panic as to whether they will be able to accomplish this Herculean feat of strength.

The athlete descends—with the spotter tight to their body—and then drives back up with all their force. Veins pop out of their forehead with everyone screaming that famous coaching cue, “UPPPPP.” The athlete stands up and walks the bar back into the rack while the room erupts: players dancing, coaches blowing whistles, bedlam. Congratulations are exchanged like a national championship has been won. The athlete has hit a personal record 60 pounds above their previous squat. The strength coach stands there reveling in the accomplishment, like their purpose has been fulfilled.

But amid all this commotion, the purpose of a 1RM test is forgotten—to gain an appropriate number to train from in the next block of training.

Video 1. Teammates fire up an athlete maxing out in a clean.

Testing for a 1RM

One rep max testing is common practice in a majority of weight rooms around the country, including one in which I have been personally employed, but what purpose does it serve? From my own undoing in the “numbers chasing game,” I can tell you that it is easy to lose sight of the purpose of testing and fall into the trap of ego lifting your athletes. I bring up most of the issues and scenarios in this article because I have made the same mistake in my career. Let’s look at the history of strength and conditioning to give us insight into this traditional practice.

I can tell you that it is easy to lose sight of the purpose of testing and fall into the trap of ego lifting your athletes, says @CoachJoeyG. Share on XAs strength and conditioning continues to mature as a field, coaches continue to find ways to validate themselves through the traditional “Max Out Day.” I don’t fault coaches for wanting to prove that their program is working, and a lot of times, external pressure dictates that coaches have a certain quota of numbers at the end of every semester. Before some of the newer technologies were created, coaches in the early days of the profession had to show worth to sport coaches to validate the necessity of their jobs, and they did this by showing increases in strength through one rep maxes.

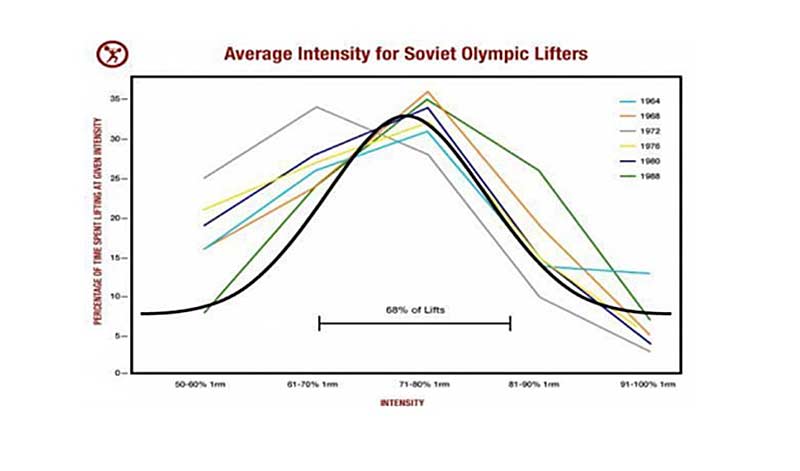

We must remember that, in the early stages of the field, strength and conditioning coaches were fighting the stigma that they weren’t necessary. Research in the U.S. was centered around aerobic conditioning, and a lot of the more advanced training methods were hidden behind the Soviet’s Iron Curtain. It wasn’t until the pioneering work of coaches like Johnny Parker, Al Vermeil, Al Miller, and many others that the strength and conditioning community in America start to use the more researched and proven training methods and best practices from the Eastern Bloc.

Though the knowledge that strength is one piece of the puzzle for increased athletic performance is now a shared philosophy for most practitioners, the allure of having bragging rights at conferences has fueled the practice of max out day to extreme ends. As the profession evolves, so should our practice of safer, accurate, and purposeful prescriptions of load—which is the end goal of one rep testing.

What Is the Specific Reason for One Rep Testing?

Mladen Jovanovic defines a one rep max as: “the maximal weight one can lift without a technical failure.” This definition coincides with what the purpose of testing should be. We should seek to create testing protocols that are repeatable and uniform in terms of standards and effectiveness.

In a sports setting, the only reason to test a 1RM is to have an accurate training number to train off in a percentage-based program. The accuracy and prescription of load is essential to a successful strength program. How can we apply overload if we don’t know the amount of load necessary to elicit stress on the athlete and promote the adaptation that drives strength and growth? Trying to program and plan training without some idea of training maximums for athletes is like playing pin the tail on the donkey in the dark.

All training is a form of guesswork and experimentation. Scientific principles clear up a lot of the guessing, provide structure, and guide safe and effective strategies for training. Coaches can’t utilize these strategies if they can’t properly prescribe the appropriate loads during the training process. “Hope” is not a strategy—planning structured overload is essential to a safe and effective training program.

It is unsafe and irresponsible to guess at load prescription. Athletes get hurt when inappropriate loads are on the bar. Speed of movement and technique become compromised when loads are prescribed without sound reasoning. I am not advocating for no heavy lifting, but I am advocating for having a strategy to safely lift heavy in a progressive manner.

One rep testing, if done, should satisfy a specific training objective, not validate or be a metaphorical pat on the back to the S&C coach, says @CoachJoeyG. Share on XOne rep testing, if done, should satisfy a specific training objective, not validate or be a metaphorical pat on the back to the strength and conditioning coach. A strength and conditioning coach shouldn’t need to feed their ego with 1RM numbers. These bragging rights violate one of my main philosophical rules: you are in your position to serve the athletes, not the other way around.

Coaches should never expose an athlete to potential danger for their own benefit.

Let’s also look at when we, as strength and conditioning coaches, actually test athletes for one rep maxes. Typically, the one rep testing happens right before a transitional period in the training year, such as the end of the semester or the conclusion of summer workouts. This is an ass-backward way, as the reason to update a one rep max is to adjust it for future training blocks. Therefore, it doesn’t make sense if we wait to test until training is completed, with rest or a competitive period following.

Why would a coach risk injury or employ maximal fatigue on an athlete leading into a competitive period? Aren’t we trying to deliver the athletes to the sports coaching staff ready to compete in their sport? Athletes don’t come to college to be professional strength athletes; they come to compete in their respective sports. Putting these athletes at risk of injury just prior to a competitive period is careless and irresponsible and should not be common practice.

Risk Reward That Comes with Max Out Day

The accuracy of testing and safety are major concerns in testing one rep maxes. The minute a coach in any capacity helps the athlete accomplish the lift, the test is invalid. Spots can increase load anywhere from 10% to 40%. Bench press should be performed with two hands, not four. If a coach is so nervous about an athlete’s safety with a given load that they must physically grab the bar, then that load should not be on the bar in the first place.

If a coach is so nervous about an athlete’s safety with a given load that they must physically grab the bar, then that load should not be on the bar in the first place, says @CoachJoeyG. Share on XThis goes back to what is the purpose in testing one rep max? If coaches take these inflated numbers and program off them, athletes could be potentially training with supramaximal loads. It is a strength and conditioning coach’s job to do no harm—so why expose athletes to unnecessary danger, when proper testing protocols would allow accurate numbers with safe attempts?

Adding a spot in any capacity immediately creates a super-maximal attempt that the tissue may not be able to handle. I have seen pecs, backs, quads, and even a meniscus destroyed during a max out day. When an injury has occurred, I’ve always had to answer not only to myself, but even more so to the injured athlete and their coaches. When the smoke clears, there is the realization that the extra 5 pounds on the squat that you, as an S&C coach, were chasing was not worth the cost of the athlete’s health. Our job is to do no harm and mitigate any potential dangers of training. Excessive spotting and supramaximal loading are dancing with the devil and serve the strength and conditioning coach more than the athlete.

Technical Standards and Reliability of One Rep Testing

The technical side of max out days is something of great importance. If an athlete can’t complete a movement with the same technical proficiency that they do in training, coaches shouldn’t use that number to train off. Board benches, partial squats, and starfish power cleans are not acceptable numbers to train off if the mode of exercise in training requires full range of motion or cleaner technical efficiency.

If an athlete can’t complete a movement with the same technical proficiency that they do in training, coaches shouldn’t use that number to train off, says @CoachJoeyG. Share on XIf the point of a one rep max is to create a number to train off, coaches should aim for the movement pattern to replicate the technique the coaches demand in training. Cut-offs should be put in place during traditional max out days based on how the movement looks versus chasing a number. Bottom line: the lifts should look the same from the warm-up through the max attempt.

Fluctuation of One Rep Max

It’s May 1, and you, the S&C coach, just concluded a successful max out day in which you observed strength gains up to 40 pounds in some athletes. You add these new numbers into their Excel workbook in the master table. The coach programs the summer workouts that start June 1 off this new number.

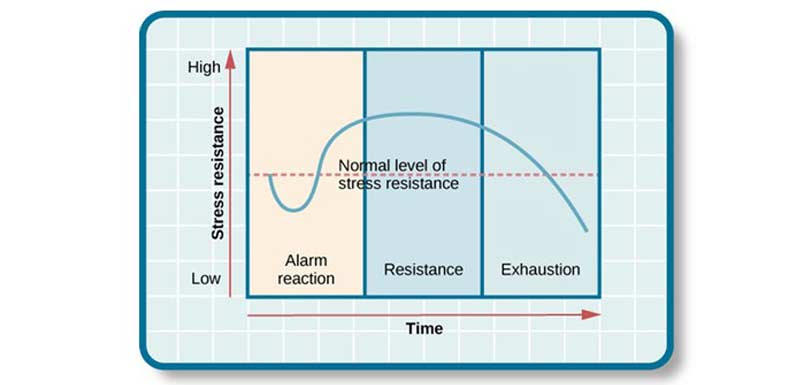

An athlete comes back off intersession break ready to get right, and when the first workout day approaches, you prescribe 75% of the newly tested 1RM for a set of four. The athlete takes the bar out and struggles with the first rep, grinds to get the second, and gets buried in the hole on the third. The coach is shocked and angered by the “lack of effort” of an athlete coming off a month break with an overexaggerated one rep max to train off. This is another situation that can be avoided by taking the appropriate steps in applying a training max.

Mladen Jovanovic proposed a viewpoint that really challenged my personal perspective on load prescription based on one rep maxes. Jovanovic stated that athletes have different levels of one rep maxes:

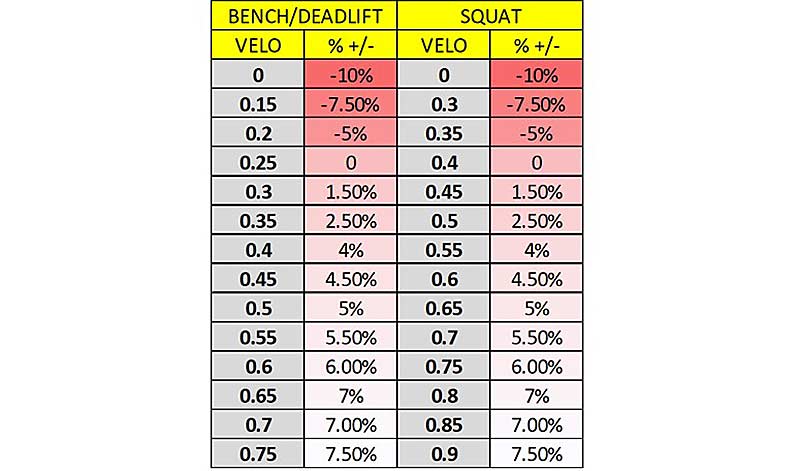

- The highest level is a competition max, which is the highest level of performance under major arousal. This could be directly correlated to the typically hyped-up max out days.

- The next level is a training max. This performance still requires a higher arousal state and can’t be repeated weekly.

- The last level is the everyday max. This number is a weight that you could walk in, load on the bar, and hit after a warm-up.

The reasoning behind Jovanovic’s viewpoint of these classifications is simple: there are huge fluctuations in absolute strength depending on various factors like fatigue state, environment, and arousal. To keep the athlete safe, it makes much more sense to undershoot a one rep max than overshoot the max and expose the athlete to the injury risk associated with faulty loading schemes. How would it make sense to use what Jovanovic defines as a competitive max as a number to train off, knowing the arousal state and environment that was necessary to produce that performance?

To keep the athlete safe, it makes much more sense to undershoot a one rep max than overshoot it and expose the athlete to the injury risk associated with faulty loading schemes, says @CoachJoeyG. Share on XTesting Is Training, Training Is Testing

The sheer planning and aftermath of a max out day takes away from the purpose of a one rep max—to train with more accuracy. A one rep max is a tool, not a training goal. Strength and conditioning coaches don’t win national championships for having a certain number of 500-pound squatters (as much as we would like to believe otherwise).

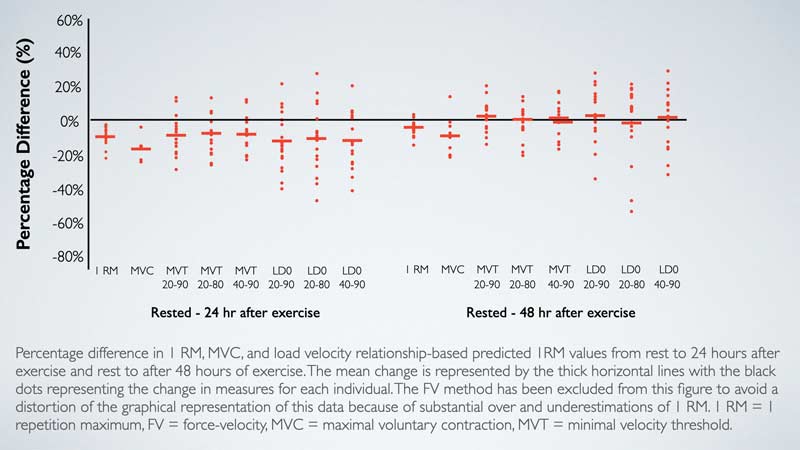

The sheer planning and aftermath of a max out day takes away from the purpose of a one rep max, which is to train with more accuracy, says @CoachJoeyG. Share on XThere are several methods that are safe and effective for achieving and adjusting one rep maxes. Load-velocity profiles have become extremely popular since the emergence of affordable bar velocity sensors hit the market. Reps in reserve (RIR) and rate of perceived exertion (RPE) also fit the bill if you have limited resources. Here at FAU, we rely on velocity cutoffs when trying to achieve an athlete’s one rep max that is currently unknown.

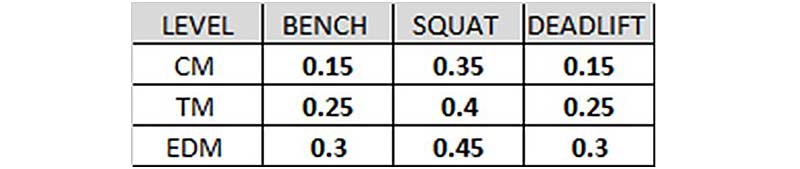

We don’t want to disrupt the training cycle, so we gather our one rep testing data on deload weeks every fourth week, which is when we drop our training volume down significantly while maintaining high intensity. This loading prescription scheme allows us to hit anywhere from 85%–90% every fourth week for a single. Like I stated, we love training heavy but in a way that doesn’t disrupt training from before that week or cause residual fatigue that lasts into the next training block. When the athletes hit the single, we record the average velocity of the movement and provide a sliding scale based on velocity for how much the athlete’s one rep max should go up or down.

Video 2. Velocity-based bar speed measurements.

Over the course of a summer, we have seen athletes progress to hitting their previous one rep max in a workout as their new 90%, faster than their previous 90% test. Because we use this method in training, the number is a valid measurement and an effective number to train off, as the arousal state, technique, and environment are that of a normal training session. It also allows strength and conditioning coaches to provide feedback to the athlete on their training status without the tapering and stress of a max out day.

Many other methods have been discussed previously on SimpliFaster. Some of these methods include RIR, RPE, load velocity profiling, and rep maxes.

Keep the Main Thing the Main Thing

Don’t get caught up in ego lifting, as it only hurts the athletes you train. Coaches must do no harm. It is a strength and conditioning coach’s duty to provide responsible training that supplements the main emphasis in training for sport, which is better sport performance.

Having X amount of 500-pound squatters and X amount of 400-pound benchers won’t guarantee a championship, even though it will make the strength and conditioning coach feel good. Training must serve a bigger purpose. Technology has provided strength and conditioning coaches with safe and effective ways to prescribe load—we need to advance with the times.

Since you’re here…

…we have a small favor to ask. More people are reading SimpliFaster than ever, and each week we bring you compelling content from coaches, sport scientists, and physiotherapists who are devoted to building better athletes. Please take a moment to share the articles on social media, engage the authors with questions and comments below, and link to articles when appropriate if you have a blog or participate on forums of related topics. — SF