Medicine balls provide a unique opportunity, enabling athletes to accelerate until the very finish of the movement—something traditional resistance training cannot achieve. Whether for increasing outputs in rotational, linear, or lateral movements, most of us throw medicine balls with our athletes to become more explosive, leading to higher movement velocities. Yet I often see implementations of this training method without the detailed look it deserves.

Okay, give me 3×10 rotational throws is a common prescription found all the way up to the highest realms of athletic training. But what kind of rotational throw is the coach referring to? Do they always have just this one specific throw in mind that they always use? When the athlete seems to be getting stronger, do they then just give them a heavier med ball to throw? I don’t know—but I do know that we are still far away in most sports in terms of the best use of this amazing training tool.

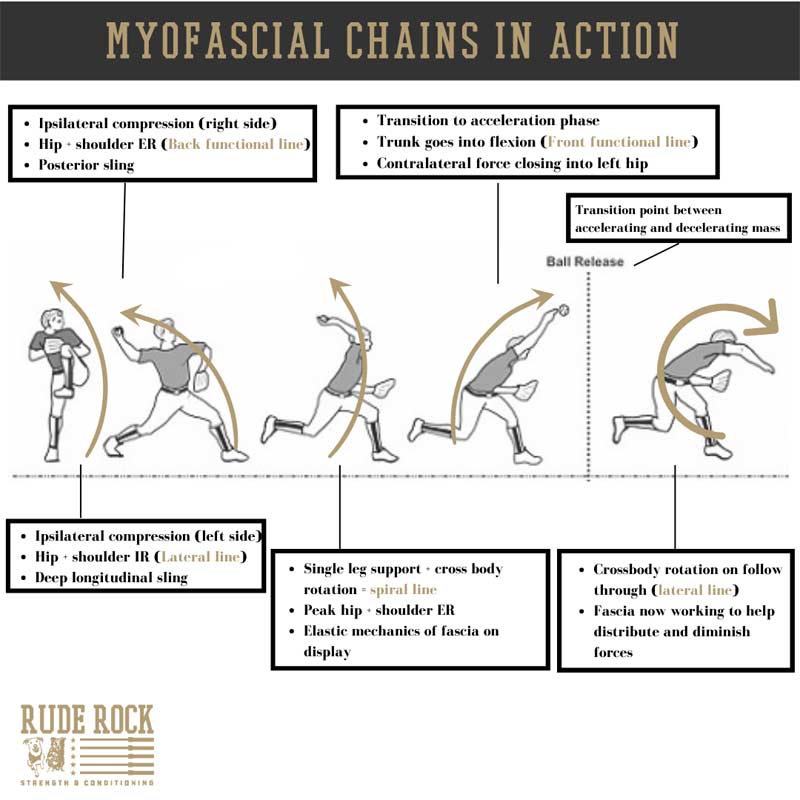

Med ball throws can be used as a bridge between the weight room and our sport-specific work, enabling us to work the ability to transfer momentum through kinetic chains in three dimensions. Share on XIn my experience, medicine ball throws can be used as a bridge between the weight room and our sport-specific work, enabling us to work the ability to transfer momentum through kinetic chains in three dimensions. I have often asked myself if there are any untouched areas in terms of progressing medicine ball throws and their intensities, apart from only increasing the weight. Doing only this might lead to submaximal results (adaptations to stimulate neural drive and motor unit recruitment), as movement velocities are slowed down, as well as increase injury risks in susceptible tissues (think of rotator cuff tendons and the like) and possibly interfere with optimal sequencing and movement rhythm.

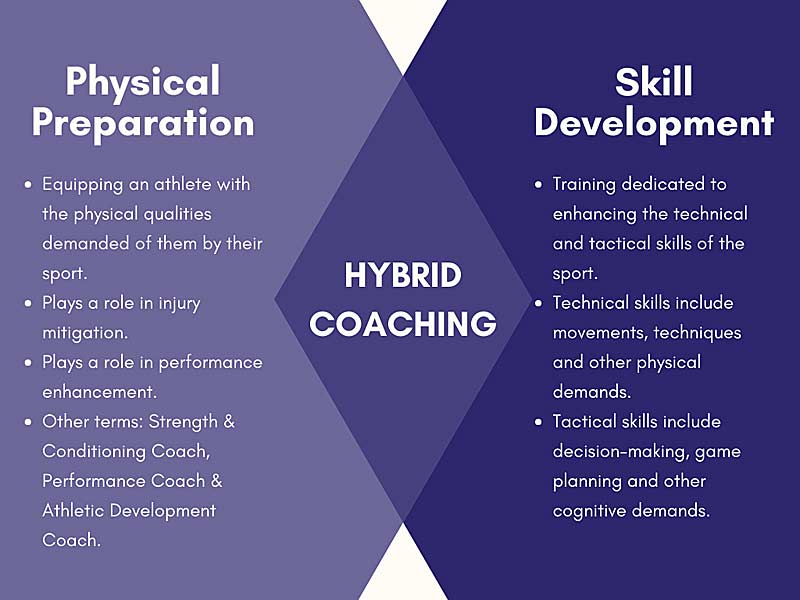

Unsurprisingly, the ultimate goal of this article is to lay out a straightforward way to progress the intensity of throwing a medicine ball by using what I call “momentum-based intensity techniques” (MBITs) to achieve higher athletic abilities for those we train.

Momentum and Impact

Momentum and impact are two of the most important terms in sport science, stemming from Newton’s Second Law (specifically the Impulse-Momentum Theorem), which basically states that:

The change in momentum of an object equals the impulse applied to it

- .

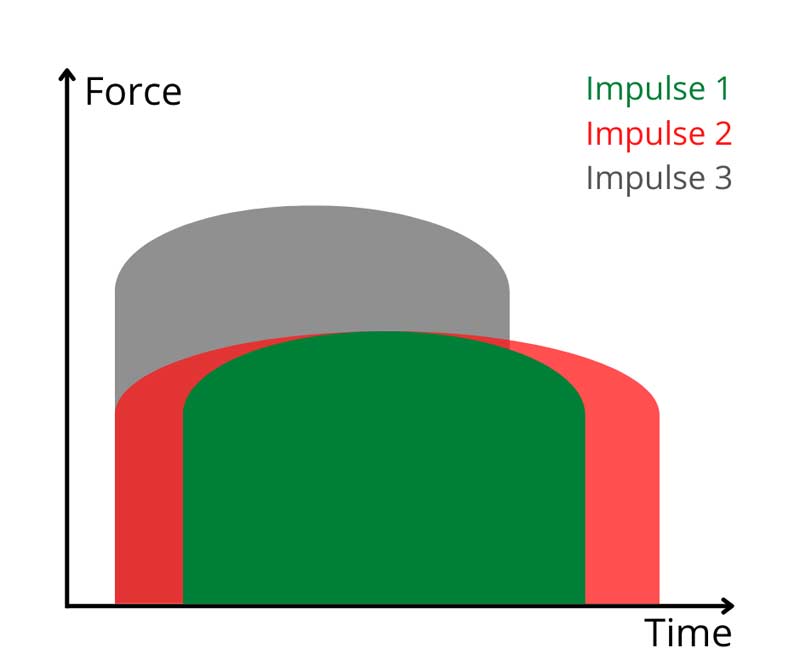

Momentum is the product of an object’s mass and velocity, whereas impulse is the product of the net force acting on an object and its duration. This means that if we want to throw a medicine ball faster, we need a larger impulse acting on it. This can be achieved either by:

- Increasing the duration that we act on the ball (see graph below: red impulse)

- Increasing the net force (while keeping the duration the same: grey impulse).

The first is possible when using a larger range of motion, the second by being able to produce a higher force faster (rate of force development and maximal strength). Although theoretically correct, the assumptions made must be taken with a grain of salt in terms of the reality of what we see happening.

In reality, if an athlete increases mean force, the duration of their actions on the ball will be shorter, as acceleration is faster. Thus, the duration will only be the same when the mean force increases if the ROM of the movement is increased in the same fashion. Nevertheless, I think the graph and described theory help us understand the fundamental relation.

But this is only one part of the story. Why? Because in sports, we commonly need to act upon an object—whether it is our body or an implement—that is moving in a countermovement action.

Think of a player who needs to make a complete 180-degree change of direction. Their net impulse needs to be comparatively larger than the one when they start from a standstill, as they need to overcome the momentum their body has built up before executing the COD task. The same must be said about throwing a medicine ball, with or without performing a countermovement, which is used to stretch the tissues that are asked to produce and transmit the necessary impulse on the implement and initiate the concentric part of the movement at a much higher ground-reaction force.

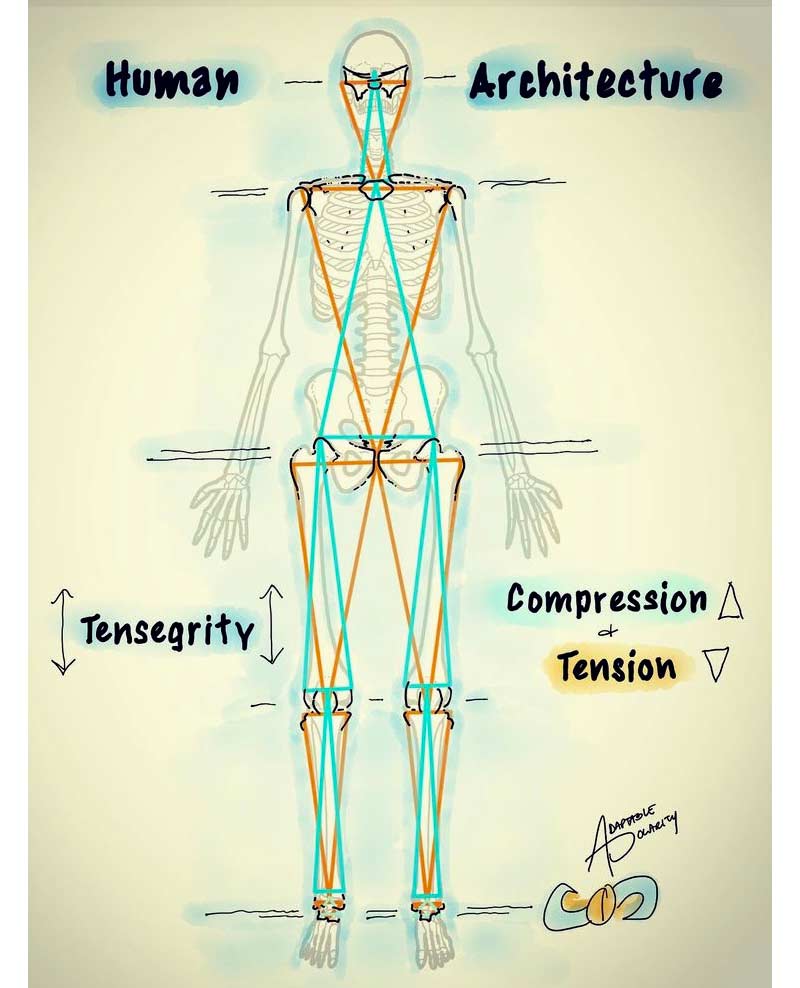

Momentum doesn’t just go ‘anywhere,’ but in a specific direction—and via our impulse, we want to redirect it to achieve the goal of our movement task. Share on XWe must remember that momentum is a vector quantity, where mass is a scalar and velocity is a vector. This basically means it is a quantity that has a direction and magnitude. Therefore, we should always remember that momentum does not just go “anywhere,” but in a specific direction—and via our impulse, we want to redirect it to achieve the goal of our movement task.

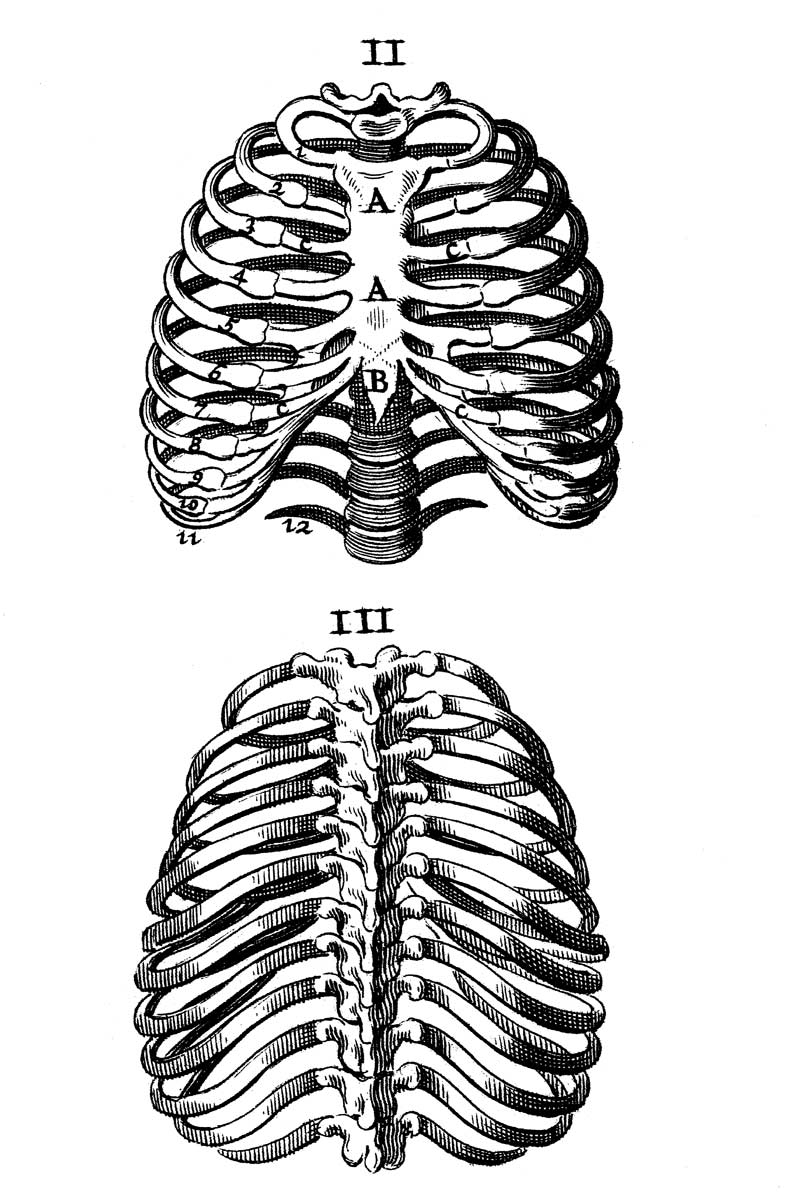

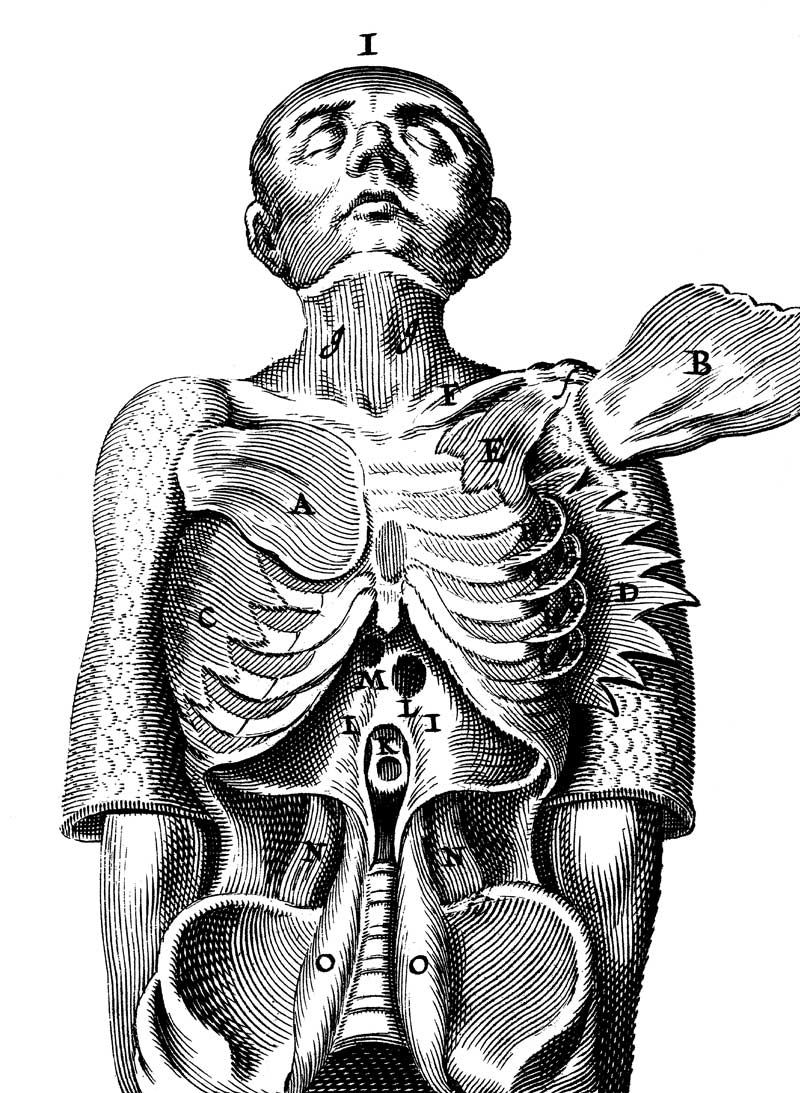

To successfully turn their momentum around, the athlete must have sufficient technical and physiological qualities. If the “negative” momentum surpasses the athlete’s ability to redirect it—perhaps because the weight of the ball is too high in symbioses with the produced acceleration via the countermovement—then the ball’s exit velocity will drop. This is despite the coach initially thinking that by implementing a countermovement, the exit velocity should be higher due to the build-up of elastic energy in connective (endomysium, perimysium, and epimysium, as well as tendons and ligaments) and muscular tissues (titin) in addition to the stretch reflexes. If our only strategy to counter such a situation would be to lower the weight of the ball, we might lose out on what we are trying to achieve: building athletes capable of dealing with increasing amounts of momentum as they develop athletic abilities.

Stemming from the argument above, the foremost question should be: how can we logically increase momentum—of the whole body and the ball—by using variations of a specific throw? Based on this question, I propose a progression regarding training for output that not only addresses increasing the weight of the ball but also the fact that a better skilled and developed player can perform tasks that are more challenging in terms of the height of momentum they face.

MBITs: Techniques to Increase Intensity by Using Momentum

There are many ways to ask more from the athlete than simply increasing the weight of a medicine ball. I would even argue that increasing medicine ball weight as the only means to increase intensity is not optimal when the goal is to increase movement velocity via neural and structural adaptations—particularly since the weight of the implement an athlete deals with in sports like tennis and javelin remain the same, while advanced players (in comparison to those of lower levels) increase their exit velocities by efficiently transferring built-up, whole-body momentum into their implements.

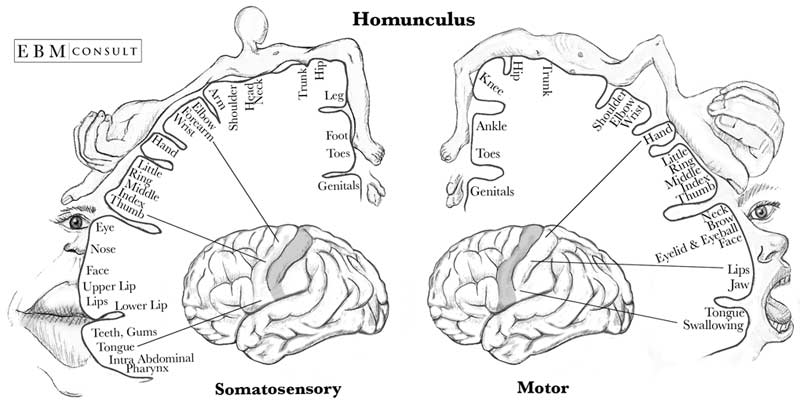

Increasing medicine ball weight as the ONLY means to increase intensity is not optimal when the goal is to increase movement velocity via neural and structural adaptations. Share on XThis also holds for athletes in sports not dealing with implements but just their bodies. Elite athletes have unique abilities in terms of using their momentum to create acceleration and output by near-perfect segmentation and sequencing of their body parts. Imagine a highly capable soccer player using two to three steps to accelerate their whole body, effectively blocking forward momentum via their plant leg to kick the ball with a very high velocity. To do this, they must learn how to manage momentum optimally.

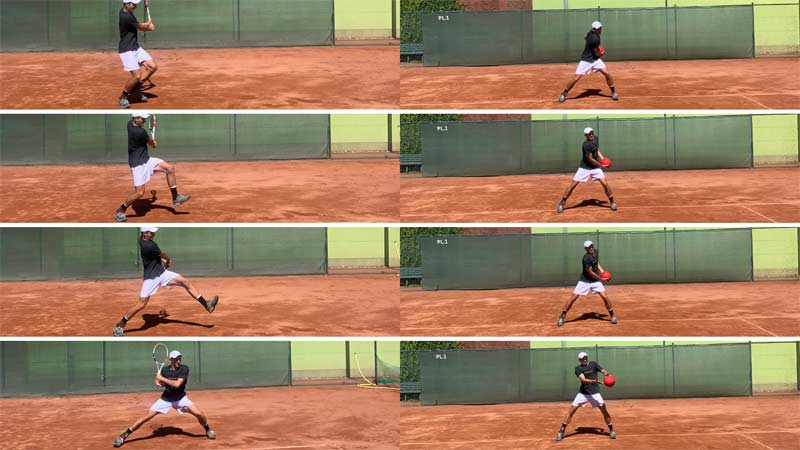

Video 1. A progression of rotational throws from a stationary, concentric-only throw to a “shock” and run-up variations.

Based on this reasoning, a much better way to increase intensity when training for movement velocity is to use methods to build momentum the athlete will need to deal with, as this will differentiate the great from not-so-great athletes: the ability to produce and deal with large momentums via impulse generation. Think of an athlete running to a COD task being able to create a higher impulse than their opponent, leading them to be faster out of that turn. Or a javelin thrower being able to use a faster run-up, which has been shown to be one of the most important KPIs for throwing distance.

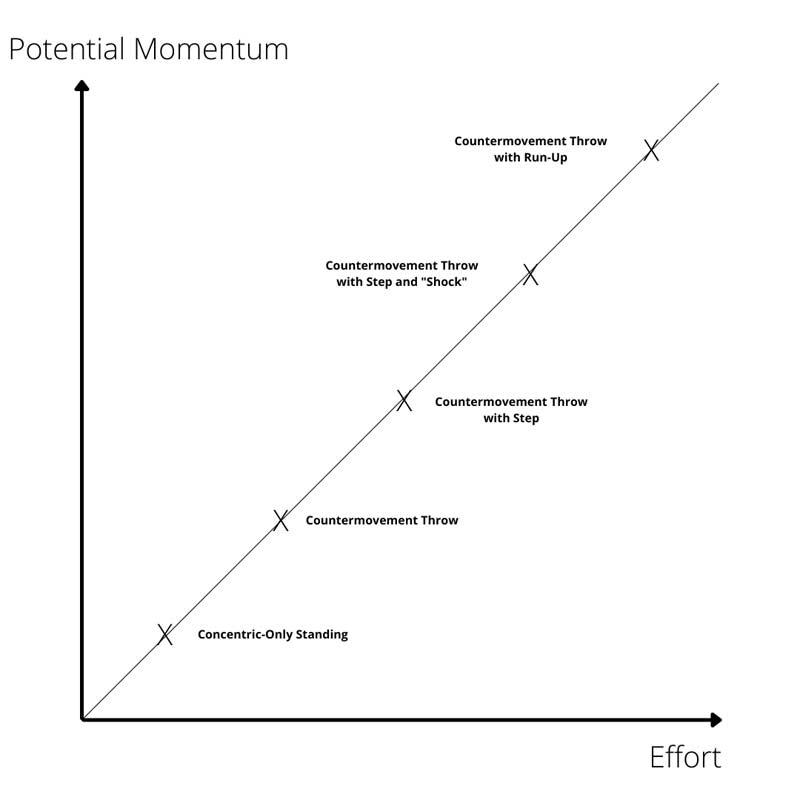

To exemplify my method of increasing intensity, the graph below shows the MBITs that I use to increase rotational movement velocities. They can be used in nearly every throw variation, such as overhead and scoop throws, as well as chest pass tosses.

The easiest throw is concentric-only—the athlete does not need to deal with any negative momentum; they only need to produce an impulse on the implement. This throw is great for beginners, as they can work on the basics of technical aspects such as hip-shoulder segmentation and the sequencing of body parts. I believe hip-shoulder separation, in particular, is something many of us try to work on intensively with most of our athletes if they play a rotational or overhead sport. The fewer components novice athletes have to deal with, the more they can concentrate on specific elements of the technique they want to work on. This is not to say that learning a movement as a whole is not useful, but depending on the context, breaking down complex movements into different parts can be of great help.

A first progression to increase momentum from the concentric-only throw would be letting the athlete use a countermovement. A countermovement while standing can be further differentiated if the athlete is allowed to move from the ground up while using their feet or if they are instructed to keep their feet relatively stable. This removes the possibility of producing more significant momentum by engaging larger ranges of motion around the ankle, knee, and hip joint via rotation of the tibia and the femur.

Adding in a pre-step is the next logical progression when using a rotational throw. The athlete can effectively load their back leg, using it to produce a much higher momentum of the whole body, which needs to be blocked by the front leg and efficiently transferred up the kinetic chain to the ball.

In this progression, what Verkoshansky termed the “Shock Method” will lead us to another increase in intensity if the athlete moves with the highest possible intent (a prerequisite of the whole progression). Reversing the momentum of a ball that is thrown to them can—depending on how fast the ball is passed—immensely intensify the negative momentum the athlete needs to redirect. The “shock” in this method comes as the body collides with an external object, leading to a sharp increase in muscle tension—which can increase impulse generation (if the momentum is not too high for the athlete to handle). You can combine this MBIT with a number of the other MBITs, such as the countermovement, a pre-step, or even a run-up.

What you must keep in mind when combining MBITs, though, is the technical level the athlete displays: the more “noise” due to variables affecting the athlete (running up, catching the ball, etc.), the less likely they will produce the highest possible outputs if their technique is not advanced enough. (This is somewhat comparable to strength outputs on unstable surfaces in traditional resistance training exercises like squats and deadlifts.)

The last step (at least relative to this example) is using a run-up into a rotational throw. This increases the momentum of the whole body a great deal. Think of a pre-step that increases the velocity of the entire body to around 3 m/s and a run-up leading to twice the velocity. This would mean a difference in whole-body momentum of 240 kg x m/s when the athlete weighs approximately 80 kilos. The athlete would need a good blocking action of their front leg, bracing it hard to conserve the momentum and allowing it to travel through the kinetic chain, finally reaching the implement. If the blocking leg cannot stay stiff upon contact, the momentum will partly vanish, and exit velocity will drop.

Building on this, the run-up leads to an even stronger collision that the athlete needs to go through, and it requires producing a large impulse on the block leg to stay stiff, while also having great movement skills and technique. Without the latter, forces arising from the collision vanish and cannot be used to increase the exit velocity of the target movement. As mentioned earlier, momentum is a vector quantity—thus, the management of masses and their direction need to be fine-tuned. An effective block is great, but if the athlete cannot funnel masses into the desired direction, forces dissipate, leading to suboptimal exit velocities.

We must be very aware of the kinds of momentum our athletes have to deal with. Share on XWe must be very aware of the kinds of momentum our athletes have to deal with. Some sports (and movements within sports) don’t require a countermovement, such as starting from blocks in sprinting. In these cases, it could be better to use a different progression model than the one proposed due to higher similarity with the target movement, muscle actions, and timing. Thus, a progression model should always be specific to the sport, the movement, and the individual athlete.

Specificity of Throwing Variation and Intensity Techniques

The chosen throwing variation should reflect the needs of an athlete or group of athletes. However, not only do the throwing variations (e.g., rotational, scoop, overhead, chest pass, etc.) need to be selected but also the MBIT the coach implements.

Think of the difference between building up the momentum of the whole body, which is possibly already heading in the right direction, and reversing a negative momentum built up by the ball via a countermovement or having to catch the ball. While the need to brace your front leg might be specific to some sporting movements, such as a tennis forehand into which the athlete can accelerate, other movements fit better with using the shock method to increase the intensity. As I work with tennis players, this could be the moment a tennis player is on the run and merely able to reach the ball, hitting it while in the air. In this instance, they need to keep their hip stable, serving as a post (I often coin it “anchor”) for the upper body to rotate around.

Thus, the coach should be familiar with what the athlete needs to work on and how to achieve that in training while not using progressions that are too “heavy to handle” in terms of momentum.

When Is the Athlete Ready for a More Intensive Progression?

A coach has multiple options to use to establish how good an athlete is in dealing with momentum. Data should be your friend here—if you have an effective sensor (e.g., the Output or, depending on the throw, the Vmaxpro), you can measure exit velocity and acceleration of your throw (Output) or movement velocity (Vmaxpro). Another option would be to use a radar gun or measure the distance the athlete can throw in each variant. (Bear in mind that measuring distance is quirkier as more variables than just exit velocity, such as release angle, determine the outcome in the case.)

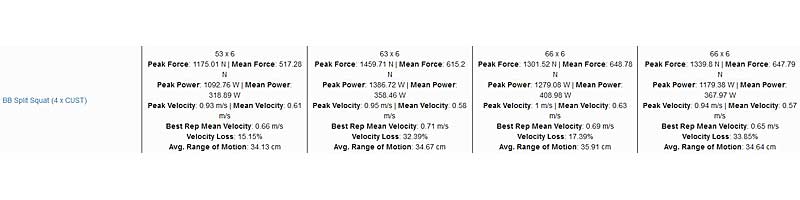

I use the Vmaxpro to determine movement velocities while performing medicine ball throws, even though it is not originally intended for such use. Share on XI use the Vmaxpro to determine movement velocities while performing medicine ball throws, even though it is not originally intended for such use. Simply attach the sensor to the wrist of the athlete and look for an exercise similar to that of the throwing variation you use.

For example, I have measured vertical unilateral scoop tosses by setting the exercise in the App to “Curl Scott.” This worked well for me and gave me interesting insights. Moving from a concentric-only to a countermovement and, finally, to a shock version of the throw, the sensor showed that the shock-version led to around 20% higher eccentric peak and average velocities compared to the countermovement throw. This is a strong increase in what an athlete’s kinetic chain on the back of their body—most importantly, the hamstrings—must deal with in terms of momentum and being able to redirect it efficiently.

Video 2. Scoop throws.

Let an athlete run through a progression and see when they begin failing to use the momentum they build up or that the ball has. Let’s say you use the cheapest way of measuring—throwing distance—and your goal is to increase output via neural adaptations in their backhand motion since they are a tennis player, and you want to add velocity to their stroke. You let them throw through the following progression, and these are the results:

The results would indicate they can deal with a pre-step, but they are not able to convert the momentum built up by running into the throw. The problem might be technical or physiological, which is up to the coach to determine via their coach’s eye and other data, such as raw strength levels and RFD measurements. Carl Valle has written about that in several articles on medicine ball training for SimpliFaster: Output is one thing, but how it was produced is another.

The decision on how to help the athlete able to bear a run-up is, again, up to the coach. Perhaps they might use a pre-step as a more volume-intensive approach, while slowly building in run-ups to prepare the athlete to deal with higher-momentum intensities. Whatever the approach, constantly measuring output via distance or movement velocities holds the athlete accountable, shows progress, and ensures they use the right way of implementation.

Constantly measuring output via distance or movement velocities holds the athlete accountable, shows progress, and ensures they use the right way of implementation. Share on XMBITs are basically comparable to the premises of Verkoshansky’s research on how to choose the right box height for drop jumps, the falling height of weights (in a machine that was built for an exercise like an MB chest pass), and an over-challenging situation when momentum becomes too high to handle for the athlete, leading to sub-maximal outputs. While slight “over-challenges” might be needed in terms of stimulating adaptations, constantly hammering an athlete with over-challenging situations might deteriorate performance while at the same time risking injury.

As with every other training modality, as trainers, we walk the fine line between enhancing performance and negatively affecting our athletes in the near term and long run. In simple language: It wouldn’t be wise to only program supramaximal-eccentric heavy back squats with an athlete struggling to even perform a technically sound bodyweight squat.

Building Your Own Progression Using MBITs

As humans, we can’t escape what Newton described in his laws, but we can help our athletes by enabling them to overcome, redirect, and manipulate the momentum they face in their sports and daily lives. This is where MBITs in medicine ball training can serve a great purpose as the base of sound progression models to enhance adaptations made from this amazing training tool.

By using momentum as a starting point for building your own model when chasing higher athletic ability, you can effectively intensify specific throwing variants without resorting to only using heavier balls. If this article contributes to helping you build better athletes, I will be more than happy.

Since you’re here…

…we have a small favor to ask. More people are reading SimpliFaster than ever, and each week we bring you compelling content from coaches, sport scientists, and physiotherapists who are devoted to building better athletes. Please take a moment to share the articles on social media, engage the authors with questions and comments below, and link to articles when appropriate if you have a blog or participate on forums of related topics. — SF