In the last 3-5 years, the subject of optimal recovery has grown to near-cliché status in the human health and performance industry. It seems like every time I turn around there are new gadgets that help athletes better connect to their recovery, as well as push the needle in the right direction when they need to. With all the tools, techniques, and gadgets out there, it can be difficult to separate the wheat from the chaff.

There’s a lot for coaches and athletes to filter when it comes to best practices in recovery, and it is way outside the scope of this article to try to cover it all. Instead, what I would like to do is provide simple, proven, and cost-effective strategies that can improve recovery using breathing techniques.

Once learned, breathing techniques are free to both coach and athlete, are virtually risk-free, and can be easily implemented into found time. This makes for an absolute no-brainer. Share on XOnce learned, breathing techniques are free to both coach and athlete, are virtually risk-free, and can be easily implemented into found time. This makes for an absolute no-brainer when deciding if you want to include these protocols on your menu of available options to improve overall adaptability and performance readiness.

Defining Recovery

Like most buzzwords, “recovery” has been overused to the point of a blandness akin to chewing on dry steel-cut oats. So it’s important that if we have a discussion about a tool to improve it, we agree upon a definition—at least while you’re reading this article. Recovery is usually thought of as the return to a normal state of mind and body: in biology, homeostasis. An interesting way to think of homeostasis is the sum range of tolerances inside an organism.

In human performance, we purposefully stress those humans in our care to elicit specific and predictable adaptations. As far as the animal kingdom is concerned, we are the only species (we know of) that purposefully doses ourselves and others with stress to elicit a prescribed adaptive response. I’ve never seen my dog running shuttles with a stopwatch in the backyard so he can finally catch that squirrel (that would be epic, though).

Of course, adding precise stress is only half of the picture. We then have to allow the system to return to a sufficient state of homeostasis that allows for more work to occur. If this cycle is repeated with proper frequency, intensity, and precision—bada bing! We are a-changin’!

Without getting too into the weeds on the aspects of specific training responses, one of the most reliable ways to measure readiness, in general, is with tools that connect to autonomic tone. The autonomic nervous system (ANS) is our deepest neural circuitry and responds to all stress in the body by managing system-wide arousal states to meet the predicted demands of both acute and predicted stress by reacting to environmental cues.

Before I go on any further, I just want to make a point that I think is essential for all coaches to hear. Sport is a neck-up phenomenon. Exercise is a neck-up phenomenon. These are both artificial environments created by humans. Your ancient stress biology has no idea in holy hell what squats are. Or what football is. It only knows how far did this push us past what we are used to? How can we avoid this and/or be ready for the next time?

Onward.

There have been a variety of indicators of athlete readiness used over the course of sports performance history, both subjective and objective. I personally know world-class coaches who place heavy stock in athlete questionnaires. Subjective feedback from athletes certainly has a place in any coach’s toolkit, but it can be tainted by personality and perspective.

Subjective feedback from athletes certainly has a place in any coach’s toolkit, but it can be tainted by personality and perspective. Share on XWhile subjective data is an important part of readiness systems, it has holes that require some objective resources. Due to the fact that the ANS is such a reliable tell of how the body has responded to increased stress (arousal), we use it as a catch-all indicator of athlete readiness.

When it comes to recovery at present, the gold standard of measurement is heart rate variability or HRV. As a rule, the more variable the heart rate, the better the recovery; the less varied, the more sympathetic and less recovered. There is certainly some nuance to this, but this summarizes the idea enough for our purposes.

What we are ultimately looking at in response to stress—training or otherwise—is if when we put our feet to the fire, the system can return itself to “normal” in a timely and energy-effective manner and be prepared to be dosed again.

Now that we have a clear operational definition of recovery, let’s tackle some obvious points before we talk about supplementing breathing techniques to enhance it. If you haven’t checked these boxes, know that the techniques that follow will only mitigate the cracks in the wall. Nobody gets to skip the basics.

How Breathing Helps

As a brief aside, I want to mention that when it comes to recovery, there are some essentials. Breath control, as much as I love it, is not one of them. The essentials are sleep, nutrition, and input management. This is an article about breathing techniques to improve recovery, but if you fail to cover these bases, you’re just breathing uphill, if you catch my drift.

So then if we agree that:

- Being “recovered” is returning to a relative homeostatic state within tolerances that allow us to receive another dose of stress.

- In general, this is best measured by autonomic tone (by HRV, for example).

Then, tools that help the autonomic nervous system return to a state of readiness are among the most helpful tools we can use.

The feedback loop between breathing and the ANS is bidirectional. This means your respiratory system responds to cues from the ANS that adjust both the rate and the depth of breathing from moment to moment, but the ANS can also receive cues from our breathing. These are complex and deeply interwoven into our physiological survival mechanisms, which help us both make efficient use of energy in the body for defense against external threats and maintain internal homeostasis.

Normally, the homeostatic feedback loop for our some 23,000 breaths per day is adjusting to our internal and external environments literally breath by breath for the entire time we are alive. The pulmonary and cardiovascular systems work in concert to supply oxygen to the body and remove carbon dioxide. Baro and chemoreceptors that live in the aorta and carotid arteries keep track of pH (metabolic stress residue is acidic) and let the heart and lungs know how often and how hard to work.

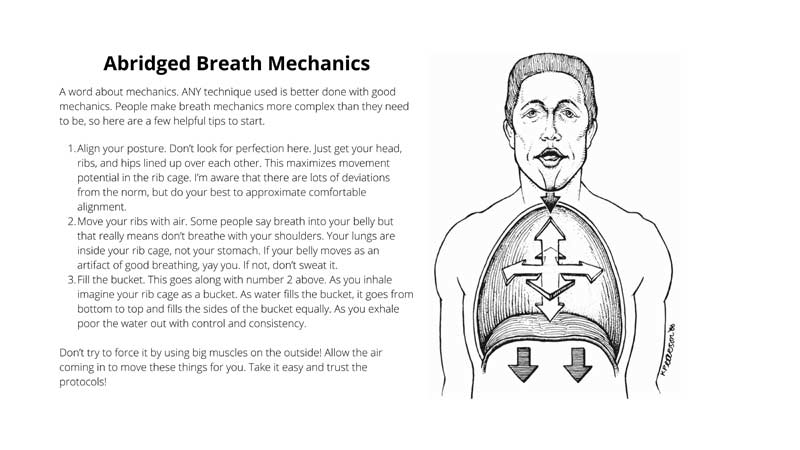

The ANS, and thus HRV, is affected by breath through both mechanical and biochemical means. Mechanically, the diaphragm has a direct impact on the fascial envelope around the heart as well as affecting hemodynamics through pressure changes in the thoracic cavity.1 The relationship between the two is in direct response to breath rate and depth, which, if you recall, is controlled by the body’s response to arterial pH.

This means by controlling skeletal muscles (diaphragm and superficial trunk and neck muscles) you can slide the dimmer switch on the autonomic nervous system from more sympathetic (lower HRV) to more parasympathetic (higher HRV). Slow, purposeful breathing (to the tune of six breaths/minute) tips us toward the parasympathetic side of the ANS, allowing for better rest.

Small, purposeful, and regular doses of properly applied breathing techniques can have a strong effect on recovery in both the short and long term. Share on XWith that said, just because we do some slow breathing for one session, that doesn’t necessarily mean we’re going to recover better all week long; however, small, purposeful, and regular doses of properly applied breathing techniques can have a strong effect on recovery in both the short and long term. This can have an aggregate effect over time that allows for faster and more complete rest, better recovery, and more energy to allocate toward performance.

Implementation Strategies

As with any tool, there are variances in individual applications, but there are some general approaches that are reliable and valid ways to improve recovery. When you first introduce new habits into your routine, microdose them into “found time.” Going from zero to hero with breathing will probably be short-lived, so instead use times that are congruent with these goals.

Protocol 1

Immediately after training is a great found time to include breath control techniques. This time is often spent talking smack with friends or looking at our phones while we pretend to cool down, so we might as well integrate some breathing into the mix.

Additionally, there is a tremendous problem with sleep dysfunction in our culture, and athletics is no exception (probably worse). Sleep hygiene is not the topic of this article, but one helpful sleep aid can be “tuning down” the system before bed with slow breathing techniques.

3-2-5 Resonance Breathing:

- Sit or lie comfortably.

- Inhale slowly through your nose for 3 seconds.

- Pause for 2 seconds.

- Exhale slowly out of your nose for 5 seconds.

- Try to use good mechanics. It matters!

This protocol is directly linked to the HRV research mentioned earlier. It coordinates the rhythms of the lungs, heart, and vascular system.

If you do the math, it is six breaths per minute. Five minutes of this, and you’ll be on your way to chill town.

Protocol 2

Breathe with purpose while you stretch or foam roll. You’ll get a bigger bang for your buck by including this easy-to-use protocol into already-planned cooldown sessions.

A great thing about breath control during these kinds of activities is that you’re having a conversation with the nervous system while you challenge tissues. That means you’ll have a deeper understanding of whether what you’re doing is perceived as a threat by the body or not.

This means you’ll be more precise in your application and yield better results for improving tissue quality, proprioception, and recovery all at once.

- Inhale slowly through your nose for 3 seconds.

- Pause for 3 seconds and at the same time isometrically contract the muscles you’re working on.

- Exhale for 4-8 seconds through your nose.

- Repeat 3-5 times while you work on the area in question.

- Practice good mechanics.

Recover Better

How well we recover from stress is a massive topic and one I’ll spend the rest of my life trying to better understand and explain. There are so many options that involve technology and a library of libraries on social media, experts with the newest this and the latest that to help you get back sooner and stronger.

There are many options to help recover from stress, but much of it is out of reach and unscalable across an entire team. Slow breathing works, it’s easy to learn, and it’s free. Share on XHere’s the thing—much of this stuff works, but just as much of it is either bull crap or out of reach and unscalable. I love ice baths but scaling ice baths for an entire high school cross country team is out of reach for most. Same for sauna. Same for Normatec boots. And so on.

Slow breathing is such a great tool because it works, it’s easy to learn, and it’s free. An average middle school soccer player can use it to great benefit and so can the MVP of the All-Star Game in the NBA.

Start with the small steps in this article and aim to use them frequently and with a focus on the quality of the application. I promise that you will not find a more ubiquitous recovery tool anywhere.

Since you’re here…

…we have a small favor to ask. More people are reading SimpliFaster than ever, and each week we bring you compelling content from coaches, sport scientists, and physiotherapists who are devoted to building better athletes. Please take a moment to share the articles on social media, engage the authors with questions and comments below, and link to articles when appropriate if you have a blog or participate on forums of related topics. — SF

Resources

1. Russo, Marc A., Santarelli, Danielle M., and O’Rourke, Dean. “The Physiological Effects of Slow Breathing on the Healthy Human.” Breathe. 2017;13(4):209-309.

2. Li, Changjun, Chang, Qinghua, Zhang, Jia, and Chai, Wenshu. “Effects of slow breathing rate on heart rate variability and arterial baroreflex sensitivity in essential hypertension.” Medicine. 2018;97(18):p e0639.

3. West, John B. Respiratory Physiology, The Essentials, Tenth Edition.

4. Levy, Matthew. Cardiovascular Physiology, Ninth Edition.

Fantastic content. Rob is an expert at making complex physiology and bio-mechanics simple to understand and execute. Need more of these from Rob!

Outstanding articles. Easy to read, understand and make applicable. Greatly appreciate the info, Rob. Keep posting!