[mashshare]

The Developmental Academy (DA) is the highest tier of youth soccer in the United States. It was started by U.S. Soccer in 2007 and is based on the philosophy of “increased training, less total games, and more meaningful games using international rules of competition.”13Almost every MLS team has a developmental academy playing in this league, and the remainder of the 74 teams in the league are comprised of the biggest youth soccer clubs from around the country. The season is nearly year-round, with short breaks during December and June-July.

Even among other developmental academies, we have a unique situation with the Real Salt Lake Developmental Academy. It is a full-time residential academy, with the players living together in dorms and attending Real Salt Lake Academy High School. The dorms are a 5-minute walk from the high school, and the school is attached to the training facility. It is about as professional of an environment as you can get in amateur athletics.

Real Salt Lake Developmental Academy is about as pro an environment there is in amateur athletics, says @CoachCotter2. Share on XWith DA teams becoming better funded and getting larger support staffs that include strength and conditioning coaches, I thought it might be useful to write an article outlining what a six-week off-season program can look like when you are in this type of truly high performance environment (i.e., no school, no time restrictions, no space or equipment limitations).

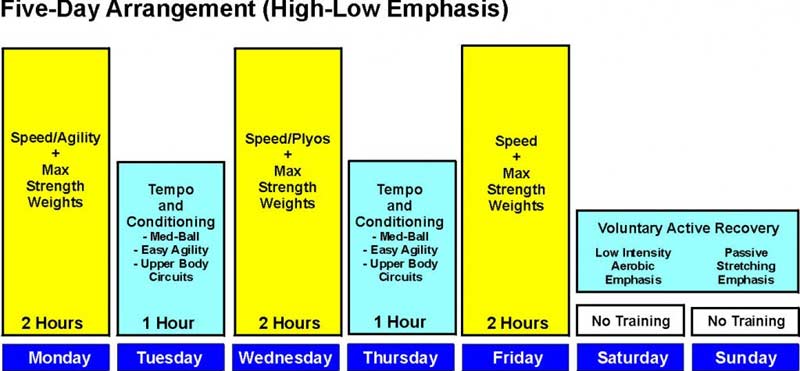

This year, our off-season began Monday, July 2nd, which was a week after our final match of the season. During this period, we train six days a week, utilizing Charlie Francis’s “High-Low Approach” to distribute central nervous system (CNS) stress appropriately throughout the week (Figure 1).

This article outlines what a typical week looks like for our RSL Academy players and how each element fits into the high-low model.

Day 1 – Monday – Testing: Vertical Plyometrics, Max Velocity Sprints, Repeat Sprints, Quad-Dominant Lift

Monday is the day of the week on which we implement our testing/monitoring protocols. This has less to do with daily monitoring from a readiness perspective, and more to do with assessing the progress of power and speed qualities week to week. Physical qualities like vertical jumping ability and maximum sprinting velocity are very sensitive to fatigue, so testing them on a more regular basis allows for a more consistent picture of how the athlete is responding to the training program; as opposed to just two snapshots in time six weeks apart, where current fatigue levels have a larger chance of being a confounding factor.7,10

We choose to do this on Monday because we are coming off a light day Saturday and an off-day Sunday, so this is the time of the week where the athletes are theoretically the freshest. This may not be the best day for these assessments for certain populations (i.e., collegiate athletes who might use the weekend for social activities rather than rest), but that is less of a worry with this population.

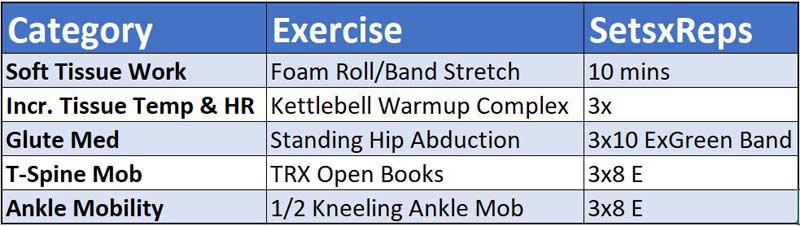

The session begins in the weight room with a standardized warm-up/movement prep, which is outlined below in Figure 2. Each speed/lift day, the warm-up programming is categorically the same (glute med work, T-spine mobility, etc.), but the exercises change simply for the purposes of staving off monotony.

After the athletes complete the warm-up sequence (approximately 20 minutes), we move on to jump testing. We utilize a three-jump countermovement jump test (hands on hips), as well as a three-jump Abalakov jump test. We are lucky enough to have access to force plates, so the jumps are performed and recorded on there. The metrics we look closest at are jump height (which the athlete is most interested in), impulse, and peak vertical force. If we can get one or all three of those metrics moving up on a fairly consistent basis, the athletes are heading in the right direction.

I believe it is very important for both the athletes and coaches to see these metrics move (or stagnate) over time. First, it gives the athletes a sense of progress— a confirmation that the time and energy that they are putting in is paying off. This is especially important in the soccer world, where even teenagers can be apprehensive about weight gain (even in the form of muscle).

The vertical jump data gives the coach something to reference when the athlete expresses concern over gaining a few pounds in the off-season. For the vast majority of the time, while the athlete may be gaining weight, the improvements in their force-producing capabilities far outweigh the negative effect of this increase in mass. Second, the data does not lie, and therefore it holds the coach accountable for the training they are delivering. It can often be a source of reflection and re-analyzation of the training program, which is important for driving continual improvement.

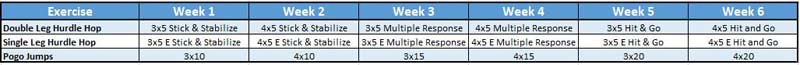

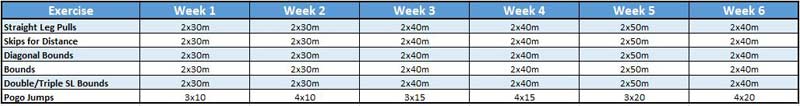

After the jump testing, we head to the field and begin our on-field warm-up (5 minutes of light jogging and dynamic movements, mostly athlete directed) and vertical plyos (10 minutes). Regarding plyometrics, we follow the basic principles Mike Boyle laid out.2Our six-week vertical plyo progression is shown in Figure 3.

As you can see, the intensity of the plyometrics increases every two weeks with weekly increases in volume. It isn’t the most aggressive plyo program out there, but I share the same sentiment as Dan Pfaff when he says “I’d rather be a mile undertrained than an inch overtrained,” and too quick of a plyo progression is a fast track to knee tendinitis. Pogo jumps are the only plyometric exercise performed more than one time a week. The intensity of these jumps is fairly low, and we put a big emphasis on ankle stiffness in the program, which is crucial for improving sprinting and jumping abilities.

Along with the plyometrics, we also mix in some wicket running to prime the athlete’s technique for the subsequent max effort sprints. These generally include a 10- to 15-yard lead-in, so the athlete can get up to speed before running through 8-10 6-inch hurdles. In my experience, no drill has improved athlete’s running technique faster and more reliably than wicket running.

No drill improves athlete’s running technique faster and more reliably than #wicketrunning, says @CoachCotter2. Share on XThe height of the wickets cues a high knee drive and the distance between wickets challenges athlete’s stride length—two aspects of sprinting that non-track athletes tend to struggle with. To determine the distance between the wickets, I rely on Chris Korfist’s suggestions of starting at 1.5 meters and increasing the distances in .2-meter increments from there. For the taller and faster athletes, 1.5 meters might be too short of a distance right away, so 1.7 meters would be a more appropriate starting point for them.

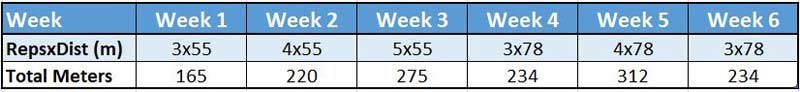

Next, the athletes run anywhere from 3-5 max effort sprints, ranging from 55 to 78 meters. We use 55- and 78-meter distances for a few reasons. First, while soccer players rarely perform a sprint longer than 30 meters in a match, we want to prepare our players for the “worst case scenario,” where they make either a long recovery run back or a long sprint forward on the counter. Second, these are not elite track athletes, and they generally reach max velocity by 40 meters; therefore, we can get away with starting our sprints at 55 meters and be fairly confident we are still getting to max velocity. Third, most soccer fields are 110 meters long, with the penalty boxes about 75 meters apart, so running end line to midfield (55 meters) or “box to box” (78 meters) is an easy designation to make. Our max effort sprinting progression is shown in Figure 4.

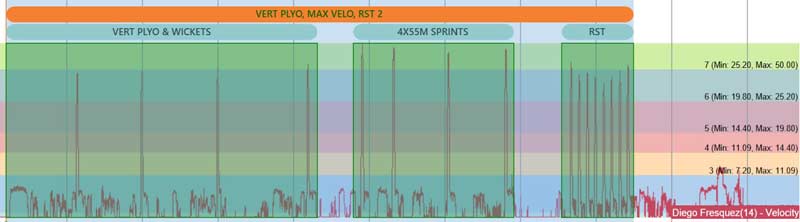

The max velocity sprints serve as our second performance test of the day, as the players are wearing GPS units so we can track improvements in max velocity capabilities over the course of the off-season. We also try and do “kinograms” (Figure 5) of each athlete sprinting every few weeks to give them some feedback on their stride mechanics.

After the max effort sprints, we finish our on-field segment with some metabolic sprint work. On Mondays, these come in the form of repeat sprints over 38 meters. We use 38 meters because that is the length between the penalty box and the halfway line on most soccer fields. The athletes sprint this distance every 30 seconds, resulting in about 5 seconds of work interspersed with 25 seconds of rest (which is comparable to many RST protocols). This isn’t meant to be too exhausting, as we still have to finish the session with a lift, so we only do 1-2 sets of 6-10 reps. The incomplete rest intervals during this exercise cause the players to get a slight metabolic (i.e., lactic) conditioning effect, which can be beneficial for an anabolic endocrine response.5

Figure 6 shows a velocity trace from one of these sessions.

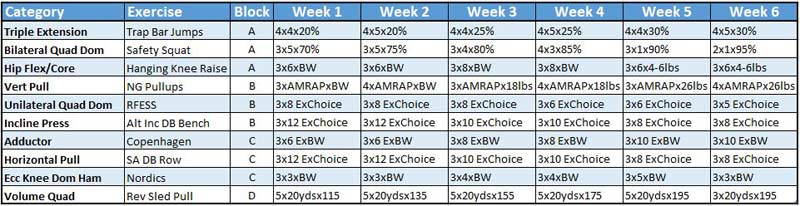

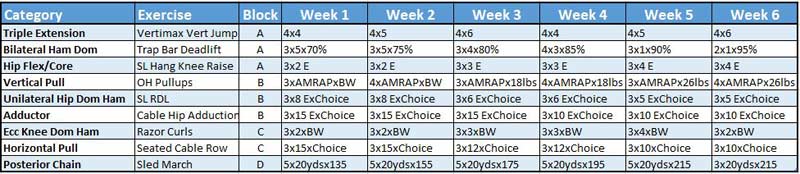

Once the on-field work is finished (approximately 45 minutes), we head into the weight room for a quad-dominant lift. With the hamstrings already being taxed from the sprinting, we choose to not load them too heavily again in the weight room on the same day without an off-day following. The six-week progression of our Day 1 lift can be seen in Figure 7 below.

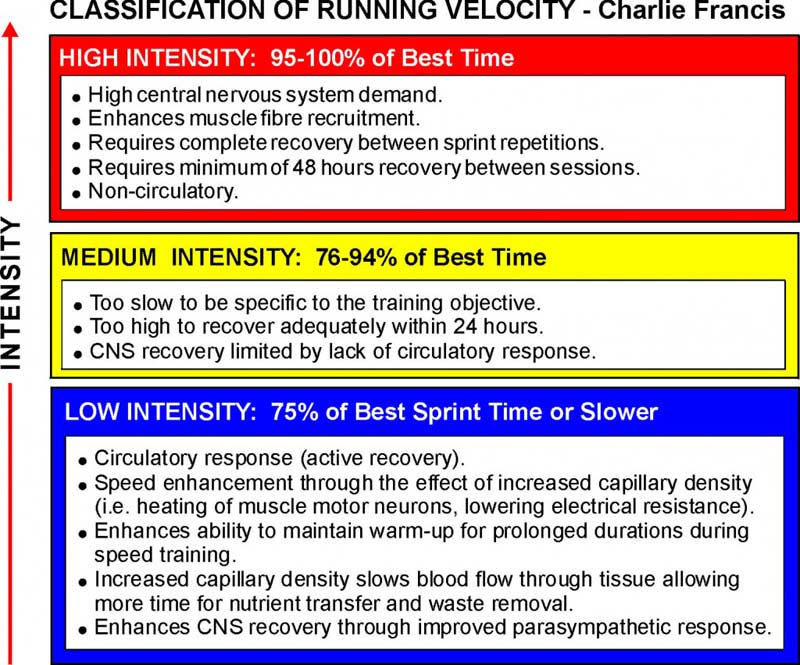

Day 2 – Tuesday – Low CNS: Extensive Tempo, Passing Patterns

Similar to James Smith,12Keir Wenham-Flatt, and many other coaches influenced by the work of the late Charlie Francis, my preferred method of aerobic conditioning is “strides” or “extensive tempo running.” The higher velocity of the runs allows the athletes to work on fluid running technique, while the longer rest periods (we use approximately 1:3 work:rest) permit high volumes of running without substantial accumulation of lactate. Additionally, in a soccer world often dominated by small sided games, accumulating a lot of distance at higher speeds (20-24 km/hour) can have a protective effect on what might be underutilized hamstring musculature. Twenty to 24 kilometers an hour is about 60-73% of our athletes’ max sprint speeds (29-35 km/hour), so it still falls into the low-intensity category in Francis’ high-low model (Figure 8).

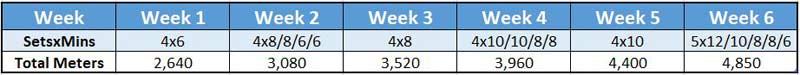

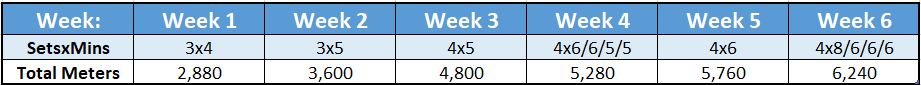

To make it simple, we utilize the soccer field for our extensive tempo runs. Players run the length of the field in 17-20 seconds (depending on the fitness level of the athlete), then use the remainder of the minute to walk the width of the penalty area (38 meters). Each rep is 1 minute, and it takes 2 minutes for one lap around the field, so 4×6 minutes is 4×3 laps. We take 2-3 minutes of passive rests between sets. With regard to volume, we follow the guidelines laid out by Derek Hansen, in which soccer players are recommended to work up to 4,500-5,000 meters of tempo running per session.

The volume increases by two laps, or 440 meters each week, which ends up being a 16% increase in volume from week 1 to week 2, with that relative change in volume decreasing each week until the jump from week 5 to week 6 is only 10%. Figure 9 shows our six-week extensive tempo run progression.

After the conditioning, we perform some sort of passing pattern for 15-20 minutes. These passing patterns serve multiple purposes. First, the players love it, so it gives them something to look forward to at the end of a conditioning session. Second, practicing these sport-specific skills under fatigue is a different stimulus for them compared to what we typically do in-season. During the year, we usually perform these types of passing patterns at the beginning of a session as a technical warm-up, when the athletes are still fresh. Finally, soccer-specific movements, such as opening up to pass and receive, changing directions, and dribbling, are unique movement patterns that stress the hip musculature in an explicit manner.

I believe that it is important to keep those movements and muscles conditioned, even in the off-season, so the first week of pre-season is not such a shock to the system. An example passing pattern can be seen below in Figure 10.

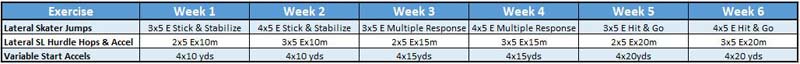

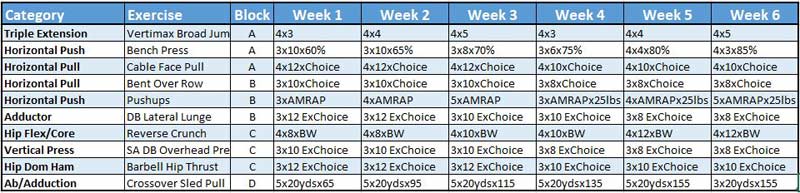

Day 3 – Wednesday – High CNS: Movement Prep, Lateral Plyos, Accelerations, Upper Body Lift

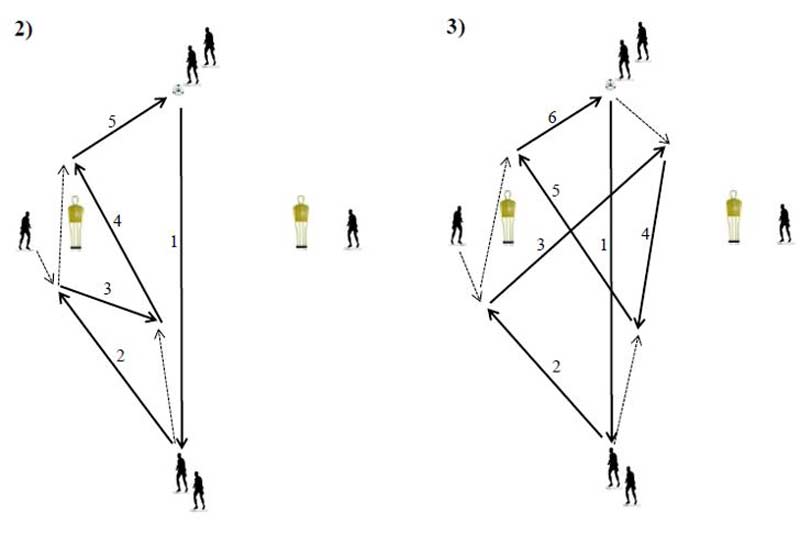

Wednesday is the second high CNS day of the week. In the same fashion as our other high CNS days, it begins in the weight room with our movement prep, then moves to the field for lateral plyos and variable start accelerations (falling, rolling, COD, etc.—see Figure 11), and ends with an upper body lift (Figure 12).

Upper body lifting is sometimes overlooked in non-collision sports like soccer. Obviously, a large amount of upper body hypertrophy is not the goal of the program, but I believe that upper body lifting with soccer players can serve two distinct purposes. First, heavy upper body movements like bench press can provide a large CNS and endocrine stimulus without further taxing the legs. Second, developing the musculature of the back through heavy pulling exercises can help athletes improve speed through more intense arm swing action.3

Day 4 – Thursday – Low CNS: Aerobic Grid Runs, Passing Patterns

On our second low CNS day of the week, we opt for slightly more high-volume conditioning. For this session, we use an adapted version of Dan Baker’s “Maximal Aerobic Grids” (Figure 13).1

Dr. Baker’s original protocol calls for athletes to run the grids at 100% and 70% of their maximal aerobic speed (MAS), but I have found it more practical with my athletes to run them at 100% and 60% MAS. When we slightly decrease the speed of the slower side of the grid, the athletes can complete more volume in a single session.

Day 5 – Friday – High CNS: Movement Prep, Horizontal Plyos, Max Velocity Sprinting, Speed Changes, Hamstring-Dominant Lift

The final high CNS day of the week is Friday. Friday is structured very much like Monday, but with the plyos horizontally directed as opposed to vertically, and the lower body work in the weight room being more hamstring dominant compared to more quad dominant on the first day of the week. You can see our horizontal plyometric exercise selection and progression in Figure 14.

We then repeat the same sprint technique work through the wickets, the same max velocity sprint work (55- to 78-meter sprint every 3 minutes), and our metabolic sprint work. The metabolic sprint work on Fridays comes in the form of 60- or 80-meter “speed changes,” where the athlete accelerates for 20 meters, slightly decelerates and cruises for 20 meters, and then reaccelerates for another 20 meters. In an effort to get a little lactate accumulation, we utilize incomplete rest periods (1:1 work:rest) for anywhere from 4-8 reps.

Finally, we finish with a hamstring-dominant lift (Figure 15). We choose to do our hamstring-dominant lift at the end of the week for two reasons. First, we trap bar deadlift on these days, which requires the heaviest load of any exercise we perform, and therefore induces a significant amount of CNS and mechanical stress. Second, the hamstrings are much more prone to DOMS than the quads (especially when eccentric hamstring work is the focus), so it makes sense to perform it going into the weekend.

Day 6 – Saturday: Extensive Intervals

On the final training day of the week, we finish with extensive interval runs (Figure 16). The players do these runs on their own, or at least that’s the idea. Ideally, these runs would be at 60-70% of the player’s MAS. So, for our example, an athlete with a MAS of 5.03 m/s would run their intervals at 6.7-7.8 mph if on a treadmill, or anywhere between a 7:45- and 9-minute mile if they are using a GPS watch.

The final extensive interval run occurs 2 days before the official first day of pre-season (August 13). For this reason, there is a de-load in the volume of this run, as well as a de-load in volume for many of the other elements of the program on week 6.

One Way to Approach Off-Season Programming

Hopefully, this article provides some ideas for other coaches for their off-season programming and how they can fit all the different elements into a traditional High-Low Model. Obviously, there are many ways to skin a cat—this is just what we decided to do this off-season, based on the reasoning stated in the piece. Please feel free to leave any comments or critiques in the comments section below, or I can be reached on Twitter @CoachCotter.

Since you’re here…

…we have a small favor to ask. More people are reading SimpliFaster than ever, and each week we bring you compelling content from coaches, sport scientists, and physiotherapists who are devoted to building better athletes. Please take a moment to share the articles on social media, engage the authors with questions and comments below, and link to articles when appropriate if you have a blog or participate on forums of related topics. — SF

[mashshare]

References

- Baker, D. (2011). “Recent trends in high intensity aerobic training for field sports.” UK Strength and Conditioning Association, 3-8.

- Boyle, M. (2016). New Functional Training for Sports(2nd ed., pp. 173-190). Champaign, IL: Human Kinetics.

- Francis, C. (2008). The Structure of Training for Speed (Key Concepts 2008 Edition)(p. 18).

- Gathercole, R. J., Sporer, B. C., Stellingwerff, T. & Sleivert, G. G. (2015). “Comparison of the Capacity of Different Jump and Sprint Field Tests to Detect Neuromuscular Fatigue.” Journal of Strength and Conditioning Research. 29(9): 2522-2531.

- Godfrey, R. J., Madgwick, Z. & Whyte, G. P. (2003). “The exercise-induced growth hormone response in athletes.” Sports Medicine. 33(8): 599-613.

- Hansen, D. M. (2014, August 27). “Optimal Tempo Training Concepts for Performance and Recovery.” In Strength Power Speed. Retrieved July 10, 2018, from http://www.strengthpowerspeed.com/optimal-tempo-training/

- Johnston, R. D., Gibson, N. C., Twist, C., Gabbett, T. J., MacNay, S. A. & MacFarlane, N. G. (2013, March). “Physiological responses to an intensified period of rugby league competition.” Journal of Strength and Conditioning Research. 27(3): 643-654.

- Jouaux, T. (2015). “Technical Warmup: 50 Exercises Handout.” In TonyJouaux.com. Retrieved July 10, 2018, from http://www.tonyjouaux.com/forcoaches/technicalwarmup

- Korfist, C. (2016). “The Art of the Mini Hurdle: Building Sprint Form.” In Simplifaster. Retrieved July 8, 2018, from https://simplifaster.com/articles/the-art-of-the-mini-hurdle-building-sprint-form/

- Marrier, B., LeMuer, Y., Robineau, J., Lacome, M., Coudrec, A., Hauswirth, C. & Piscione, J. (2016, April). “Quantifying Neuromuscular Fatigue Induced by an Intense Training Session in Rugby Sevens.” International Journal of Sports Physiology and Performance. 12(2): 218-223.

- McMillan, S. & Pfaff, D. (2018). “The ALTIS Kinogram Method.” In Simplifaster. Retrieved July 8, 2018, from https://simplifaster.com/articles/altis-kinogram-method/

- Smith, J. (2014). Applied Sprint Training(pp. 38-42). n.p.: Vervante.

- “What is the Developmental Academy?” (n.d.). In U.S. Soccer Developmental Academy. Retrieved from http://www.ussoccerda.com/overview-what-is-da