What I’ve learned over the years is that there is seldom a best way. Even more rare is a right way. And, almost never, is there an only way.

Like most coaches, I struggled to fully understand that early in my career. When you first jump into an industry, you’re eager to prove yourself, show your worth, and earn the respect of your peers by trying to convince others you have the best, the right, or the only way to do something.

As you quickly find out, it doesn’t work like that. This is why I love to operate in those gray areas. This profession is all based on a continuum—we have extremes in every topic. Sure, the extremes will work for some, but not all. The conservative route will also work for some, but not all. Finding the balance between those extremes is what is going to help the most athletes possible, which is what we all want to do at the end of the day.

Finding the balance between those extremes is what is going to help the most athletes possible, which is what we all want to do at the end of the day, says @JustinOchoa317. Share on XOne gray area that I operate in is blending skill training with general performance training, a combination that many frown upon or outright avoid. It’s often said to keep the sport the sport and keep the training the training; but again, there are some coaches who can do both at a high level and why would we not want to help the athlete in as many ways as possible?

In this article, I’ll share my personal journey of how I now view this gray area and how it has changed in the past decade, as well as dive into some methods that have worked well for me. Although my perspective is from a basketball lens, these principles can be applied to all sports and training.

Defining Skill Training

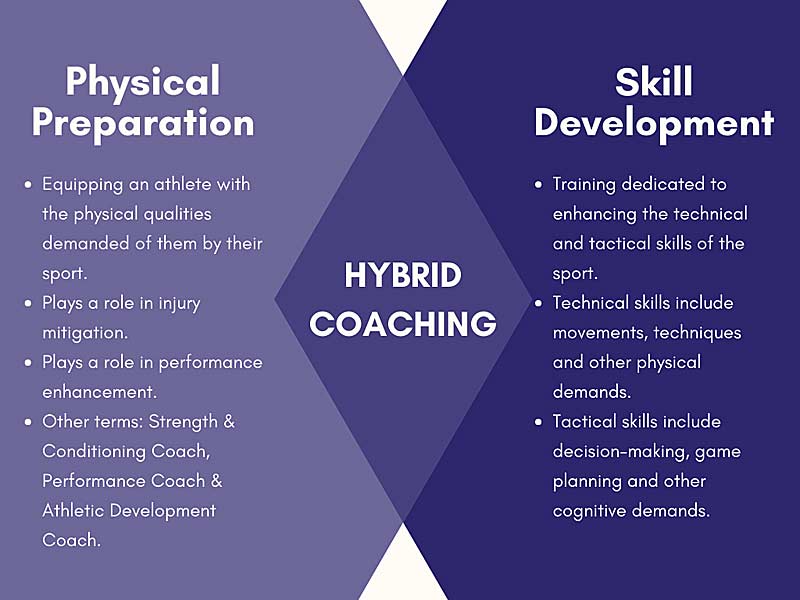

For a general working definition of what skill training is, I define it as training dedicated to enhancing the technical and tactical skills of the sport. This would include:

- Technical skills, which are the exact movements and physical tasks an athlete needs to compete in the sport.

- Tactical skills, which are the strategic, decision-based demands an athlete needs to compete in the sport.

A simple example of a technical skill in basketball would be the ability to deliver a bounce pass or chest pass to an open teammate. An example of a tactical skill in basketball would be knowing when to perform a bounce pass instead of a chest pass, and why.

Skill development is a crucial piece of the total athletic development puzzle for all sports. This is the foundation an athlete can build on, but also the repertoire that an athlete can constantly refine for the rest of their career.

Defining Performance Training

On the flip side, we can define performance training (aka strength and conditioning) as the general physical preparation of an athlete. This training is dedicated to equipping an athlete with the physical qualities demanded of them by their sport. This training is not only for performance enhancement, but also can serve a role in the mitigation of certain injuries and overall health and safety of an athlete.

Again, this is also a vital piece of an athlete’s development and it is equally important for the athlete’s long term success.

Stay in Your Lane

As coaches, it’s ingrained in us to work within our scope of practice. Strength coaches don’t diagnose medical conditions, athletic trainers don’t conduct a lifting program, physical therapists don’t perform surgery.

As coaches, it’s ingrained in us to work within our scope of practice, says @JustinOchoa317. Share on XSure, some individuals have the knowledge to cross these lines—it was never meant to be about the ability to do so, but rather the liability to do so. Each profession is set up with their specific services because that is what they are licensed and/or insured to perform.

I agree with this line of thought, because it keeps the safety of our athletes at the forefront. Somewhere along the lines, we associated scope of practice with staying in our lane. And to me, those are not the same thing.

Many coaches preach to stay in your lane, but the problem is that this is a very subjective line to draw in the sand. How do we even define what our lane is?

My aha moment was that my lane was never about one service to provide, but a solution to provide. My lane is basketball development. It wasn’t only strength training for basketball players. It wasn’t only speed and agility training for basketball players. It wasn’t only skill development for basketball players. It wasn’t only coaching a basketball team.

It is pure, holistic, multi-faceted basketball development.

So, I decided to pursue that and ended up wearing all those hats for the betterment of my athletes. My hope is that reading this is resonating with you right now, especially if you have been holding yourself back from operating in this gray area.

The Methods

Since we defined performance training and skill training separately, let’s look at how we blend the two. This hybrid approach obviously requires some personal experience and background context in multiple facets of the sport in consideration, but by no means do you have to be a former professional athlete in any sport to turn into an effective coach in that sport.

The first box to check would be to make sure you’re continually perfecting your craft and refining your skills in all of the areas you’re coaching in. It’s easy to get comfortable with what you know about a subject and neglect furthering your understanding on a deeper level, especially if you’re having success in it. Lifelong learners are always going to find ways to add value, regardless of what industry we’re talking about. In fact, one of the best parts of the hybrid training approach is that we get to view athletes through multiple lenses, which will give us a range of new perspectives and learning opportunities along the way.

Lifelong learners are always going to find ways to add value, regardless of what industry we’re talking about, says @JustinOchoa317. Share on XWhen you see an athlete in multiple environments, this can also provide a ton of usable coaching information. Even if you don’t use a hybrid training approach, it’s extremely beneficial to watch your athletes play their sport. I’ve previously written about how studying game film can impact programming for performance training, but seeing them play, practice, and train for their sport in-person is even better.

If you’re using a hybrid training model, what you see in sport can dictate some performance-based programming decisions for you in the weight room. On the flip side, what you see in general performance training sessions can help drive decisions for you on the sport side. After all, we want synergy between these two facets of training to give the athlete the most out of both. This is a major upside of the model because all of the info is consistent and streamlined by being run through a single entity.

As with any training, whether skill or performance, it’s always a great idea to begin with an assessment or some form of baseline. We need to collect objective data relevant to the athlete and their sport. We can also collect subjective pieces of info and feedback directly from the athlete. This is a critical step in the training process that many still ignore. I can’t stress enough how important it is to establish a starting point for measuring progress.

As with any training, whether skill or performance, it’s always a great idea to begin with an assessment or some form of baseline, says @JustinOchoa317. Share on XFor example, objective data for a college basketball player could look like:

Performance

- Vertical Jump

- 20 Yard Sprint (0-10, 0-20 and 10-20)

- Trap Bar Deadlift Load Velocity Profile

Skill

- Field Goal Shooting Percentage (in game or in training)

- 3-Point Shooting Percentage (in game or in training)

- Turnovers Per Game (in game)

We can test the performance portion and we can look at official statistics (or training stats) for the skill portion. These are all things that we can work to improve and objectively measure to see if that training had positive effects.

Examples of subjective data we can utilize could include:

- The Eye Test: Can we see a difference in any technical, tactical, or performance qualities?

- Athlete Feedback: Does the athlete see or feel a difference in any technical, tactical, or performance qualities?

- Outsider Feedback: Do those in the athlete’s network (coach, parents, teammates, etc.) see a difference in any technical, tactical, or performance qualities in that athlete?

My advice is to have a general system in place with some one size fits all key performance indicators and leave some room for individualization that you can sprinkle in on a case-by-case basis, depending on the athlete in front of you. The moral of the story: have something in place and grow it as needed.

Just as a strength and conditioning coach would do after an assessment or a skill development coach would do after an athlete’s first workout, a hybrid coach develops a needs analysis for the athlete and programs for them based on that. The only difference is that a hybrid coach is going to program for both skill and physical preparation simultaneously.

And it’s really all the same.

We begin with the low hanging fruit, use progressions and regressions to get the adaptations we want, track progress, reassess, and repeat the cycle.

Need to improve an athlete’s lower body strength? A healthy dose of squat, lunge, and deadlift variations will do the trick. Need to improve an athlete’s jump shot? A healthy dose of shooting drills will do the trick.

It’s not easy, but it really doesn’t have to be overly complicated.

Below are three hybrid methods that have worked well for me in the basketball world which can be applied to other sports in their own right.

1. Sport Movement Data

One of the most powerful things I’ve used in this hybrid training model is quantifying sport skills or sport movements. This can be done in so many ways, depending on the tools you have.

I am an avid user of the 1080 Sprint, which makes it really easy for me to hook an athlete up to it and have them perform a dribbling sequence or some sort of acceleration-based basketball skill and get immediate feedback on their force, power, and speed outputs.

I’ve even talked to coaches and athletes who are utilizing these same concepts with wearable EMG garments. I’m not quite there yet either financially or, admittedly, in my understanding of the data, but it’s another option that can give really useful data.

Like I said, I love the 1080 Sprint, but it’s not exactly the most common thing to see around a facility. Don’t have one? That’s okay, you can still use timing systems to get a similar result. We’ve used Brower Laser Timers, the Freelap Timing System, Smart Basketballs, Accelerometers, and a good old-fashioned stopwatch to time drills.

Not only does this give us output data on specific, sport-related movements, but in-session it can also gamify things and really bring the intensity of the workout up a notch. It’s amazing to see an athlete’s competitive nature kick-in and turn what was already a really good session into one that gets talked about for weeks to come.

It’s amazing to see an athlete’s competitive nature kick-in and turn what was already a really good session into one that gets talked about for weeks to come, says @JustinOchoa317. Share on XA few major things I look for are sport actions that can be quantified and linked with a training option that we can not only use to improve that sport action, but also quantify on its own.

For example, change of pace is a huge component of basketball. We don’t want our players to be flying around the court at top speed and completely out of control: rhythm, pace, balance, and control are vital.

If we want to help an athlete improve their change of pace, we use the 1080 Sprint to quantify that attribute in various attack moves. In training, we need to help them decelerate cleanly, learn to relax, and then turn that small moment of relaxation into violent re-acceleration. All things we can train in the weight room and in our SAQ work, as well as practicing the actual skill.

Video 1. I want to measure change of pace and track progress on it.

Programming may involve box squat variations to overload the eccentric phase. This can help improve an athlete’s deceleration qualities, as well as contribute to acceleration speed due to increased eccentric and isometric strength, which is massively important in early acceleration.

We may also include some box squat variations and concentric-only lifts like pin squats or dead stop trap bar jumps to help the athlete improve their rate of force development, another major factor in that re-acceleration phase.

From an SAQ perspective, we can sprinkle depth jumps, drop jumps, and resistance sprints when possible, based on the athlete’s total workload. On the court, we can practice a lot of hesitation and deceleration moves to fine-tune the pace we’re looking for.

Of course, this changes from athlete to athlete, but this is just a general outline of a potential thought process that you can apply to whatever sport skill you’re focusing on. I really love the system of quantifying a sport skill, finding ways to globally improve the physical qualities relevant to that skill, and then putting it all together with skill training.

2. Contrast Sets

Another concept we can carry from performance training into skill development is the idea of contrast sets. In the weight room, we utilize contrast sets to enhance central nervous system activation and neural drive of a given movement. Using a heavy compound lift followed by a violent ballistic or explosive movement of the same pattern gives us that potentiation effect to help the athlete produce more power. This potentiation can give the athlete both acute and long-term training adaptations, including improved motor unit recruitment, rate of force development, and power output.

Video 2. The idea is that we can load a basketball movement to create a high-intensity muscle contraction, then contrast that with the same movement without load.

I use a ton of contrast sets on the court as well—and these same principles can be applied to all sports. Same concept, different environment. We load a movement with cables, bands, weighted balls, etc. to perform a sport movement, then immediately perform the realistic sport movement to follow.

For example, we can use something like a VertiMax and heavy ball combo to load a jab series. This challenges the athlete’s mobility, control, and ability to perform the technique precisely. In contrast, we can work the moves in on a dummy defender in a drill setting to give the athlete that extra burst to keep all reps at game speed with extreme intent.

Another thing I’ve loved experimenting with is towing an athlete into a deceleration-based basketball movement using the 1080 Sprint. This applies a slight amount of overspeed to the movement, challenging their ability to decelerate and control the movement, as well as exciting the central nervous system. While observing the move immediately after, I noticed insane footwork and stopping on dimes to complete the move.

Note: I would not recommend using this method with a basketball player’s jump shot mechanics. Using a weighted ball to shoot is not going to give us the same training effect as in cuts, sprints, changes of direction due to the delicate nature of an athlete’s individual shooting form and may actually alter mechanics in a negative way.

We only work these in once or twice a week for about 20 total reps each time, but the feedback I’ve gotten from athletes regarding these contrast sets has been amazing. When an athlete says they feel the difference, that’s a huge win.

When an athlete says they feel the difference, that’s a huge win, says @JustinOchoa317. Share on X3. Movement-Based Programming

I’ve started to use the phrase “Movement > Moves” a lot, meaning that if we can help our athletes move efficiently, we give them the tools they need for any move they want to do.

Lifting-wise, we don’t have a leg day, chest day, back day, etc. We have a push day, pull day, and multi-planar day. Or we have an acceleration-based day, top-end speed day, or change-of-direction day. The skill work we perform on the court is just another puzzle piece in the bigger picture, fitting in perfectly with the off-court work.

We want all of these training sessions to feed each other. Since some athletes may knock it all out in one session and others may split it into two separate sessions or days, we want there to be a common theme and training goal behind each drill, lift, and session.

Don’t get me wrong, I love to experiment and troubleshoot, too. Some days we get off the program and go rogue down a rabbit hole. It’s not a script, it’s just a template to keep us focused on the athlete’s goals.

Video 3. Speed and agility day on the court.

We’re not robotically practicing situations we hope happen in a game the same way they happened in training—we’re equipping athletes with the physical and mental qualities needed to use various concepts from their training in the game without even having to think about it.

We’re equipping athletes with the physical and mental qualities needed to use various concepts from their training in the game without even having to think about it, says @JustinOchoa317. Share on XLessons Learned

At the beginning of the article I stated that there is rarely a one way, a right way, or a best way to do anything. I have, however, learned some lessons the hard way. Through trial and error, countless failures, and just flat out being wrong about a lot of things, I’ve been able to put together a pretty solid recipe of things that have worked for me and may also work for others.

Here are the five most notable lessons that failure in the hybrid space has taught me.

1. The Importance of Load/Athlete Management

Yes, we know load management is a crucial element to any kind of training program, but I can’t emphasize this one enough for hybrid coaches. This is the biggest benefit of the hybrid approach, but it can easily be the biggest drawback if not carefully managed.

Rarely do athletes actually overtrain; what typically occurs is an athlete will under-recover. Big difference. Athletes must be taking nutrition, hydration, sleep, mobility, mental health, and all other components of recovery seriously for any of their training to truly pay off.

So while load management is absolutely critical, we can’t forget about athlete management. This means relationships. This means communication. This means we need to go deeper than lifts, drills, and readiness scores. We need to really get in tune with the humans in front of us and see them as people first, athletes second.

So while load management is absolutely critical, we can’t forget about athlete management, says @JustinOchoa317. Share on XWhen we can help manage our athletes and the load or stress they’re under, we can really make our best decisions as to what training we need to apply and in what volumes or intensities.

2. Be Prepared for Push-Back

Bad news about hybrid coaching: you will most definitely get some push-back. People who view you as a performance coach will question your ability to coach the sport. People who see you as a sport coach will question your ability to be a performance coach.

It’s okay.

Many people won’t understand your vision. As long as you have a vision, it’s up to you to bring it to life. There’s no need to worry about what others think. Just become laser-focused on the athletes and people who you need to serve and the results will come.

And when the results come, then people will start to see the vision.

3. High-Impact of Individualization

Again, one of the major benefits of handling an athlete’s programming from sports skill to sports preparation is that you can manipulate so many variables to really fine-tune what the athlete needs. So much of training is general—which is perfectly fine, but the more individualized you can make a program, the better.

Individualization isn’t easy, but it can be simple. It doesn’t mean every single athlete must have a unique program from top to bottom, but rather each athlete can have certain variables adjusted to make their program more focused on their needs.

A common example I see with the basketball players I work with is how they produce force, power, or speed. Some athletes are elastic and bouncy, but may lack pure force production. Others are muscle-dominant and force driven, but lack elasticity. They could have similar RSI, vertical jump, and speed numbers, but their strategies to get there are totally different things.

These athletes can train together and even use the exact same exercise selection in some cases. However, their target bar speeds may be different, their volume may be different, their warm-ups or plyo work may be slightly different. The skeleton of the program doesn’t have to be completely turned upside down to still get really good results.

The skeleton of the program doesn’t have to be completely turned upside down to still get really good results, says @JustinOchoa317. Share on XWe can use both sport assessment and performance assessments together to build a roadmap for the athlete. If the athlete can’t master a sports skill, maybe it’s due to lack of some sort of physical trait; we can train to enhance that, then apply it directly to the sport skill.

If it works, we know exactly why. If it doesn’t work, we still know exactly why. It’s a win-win.

4. Use a Scale of Specificity

A great deal of what we do as coaches can be measured on a continuum—in terms of the hybrid coaching style, the continuum or scale in this case can be how sport specific to make something, and when.

Do we want athletes turning everything into a sport-mimicking drill? No.

Do we want athletes only doing the 5/3/1 program for the big 3 lifts? No.

We probably want them in the middle somewhere depending on the athlete, the time of year/season, their goals, and their current level of athleticism.

Video 4. A sample of some of the programming decisions we can make when blending general to specific training.

I’ve turned to a scale of specificity to help me organize programming when dealing with athletes in the weight room and in their sport.

I’ve turned to a scale of specificity to help me organize programming when dealing with athletes in the weight room and in their sport, says @JustinOchoa317. Share on X

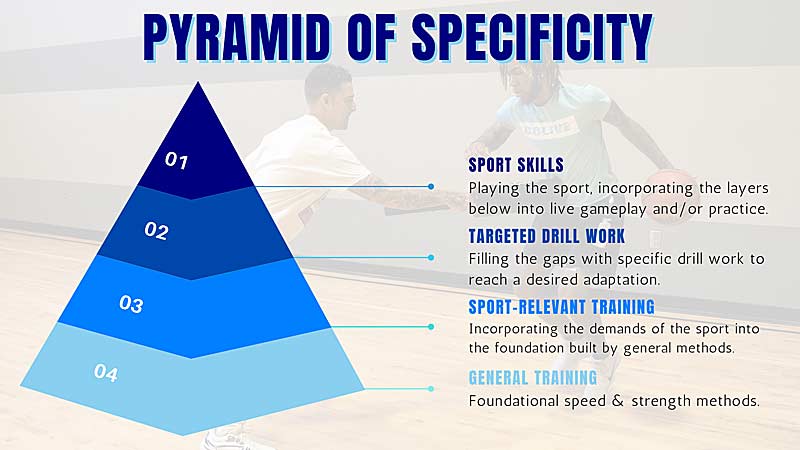

From bottom to top:

- General Speed or Strength

- Sport-Relevant Speed or Strength

- Targeted Drill Work

- Sport Skill

We want the bottom levels of the scale to feed the higher levels. This scale can help you properly program and dose athletes with lifts or drills that make the most sense for the stage or training or environment they’re in.

Starting at the bottom, with general speed or strength, this is exactly what it sounds like. These are the basics and fundamentals of speed or strength training that we can use to set a proper foundation for future training. Foundational movements in the weight room include the squat and hip hinge (as well as unilateral variants of both), upper body pull, upper body push, rotational movements, and carrying. On the speed side, we have sprinting, jumping, landing, cutting, shuffling, and throwing, although that could be more of a weight room movement as well.

General speed or strength work casts a wide net and allows athletes to reap numerous benefits of training before focusing too much on minutia and missing out on the low hanging fruit.

General speed or strength work casts a wide net and allows athletes to reap numerous benefits of training, says @JustinOchoa317. Share on XNext on the scale comes sport-relevant speed or strength work. With a solid foundation set, we can now start to sprinkle in variations of those foundational movements with a little bit more focus on exactly how it can transfer to the sport. Some of the variables that can be altered to make a general exercise more sport-relevant include posture or body angles, duration of activity, overall volume or intensity, target bar speed, equipment or devices used in the exercise, and training environment or surface just to name a few.

Whether it be strength, power, speed, or even conditioning, the goal here is just to build upon that general baseline and add elements of the actual sport to the program.

Next we can add in specific drills that we think fill any gaps that may exist after the first two layers of training. It could be a purely sport-driven drill, a completely physical preparation drill, or a hybrid of the two.

And then, finally, comes pure sport skill. Just practicing the sport. The most sport-specific training that exists.

The goal is to build a holistic plan that allows the general to feed the specific.

5. Invest in Your Education

Lastly, continue to invest in your continued education. This doesn’t always mean investing financially, but also investing your time and energy into your education in outside-the-box ways. We can get a ton of information from clinics, courses, and certifications, and obviously those are great options for continuing education.

Don’t let those be your only forms of education though—other great forms of continuing education are less formal options such as networking, experimenting on yourself and…I can’t believe I’m about to say this…social media.

Networking and communicating with other coaches, athletes, and professionals in all industries is one of the best ways you can extract successful behavior and apply it to your own life.

Experimenting on yourself is great because you can then scrap all of your bad ideas and protect your athletes from them; the bad news is you may have to deal with the negative consequences of those bad ideas, but that’s okay, it’s kind of heroic in a way.

Experimenting on yourself is great because you can then scrap all of your bad ideas and protect your athletes from them, says @JustinOchoa317. Share on XIn all seriousness, it’s very important to practice what we preach as coaches. Sure, the levels of intensity or activities will change over the years, but at least having some relevant skills similar to the athletes you work with can make a huge positive impact on their buy-in.

And, lastly, social media. This ties into communication and networking, and there’s a ton of great info out there—but also I want to look at the flip side. The most underused benefit of social media is using it to view examples of what you shouldn’t do.

I can’t tell you how many times I’ve been scrolling through my feed, saw a video, and immediately thought, “Wow, I don’t think I would ever need to do that.” That goes into the mental Rolodex and honestly helps create a better organization system for when I go through those experimental phases with new exercises.

Never get comfortable. Never get complacent. Strive to master your skill set and fine-tune it daily so that you and your athletes can have the best experience possible.

Since you’re here…

…we have a small favor to ask. More people are reading SimpliFaster than ever, and each week we bring you compelling content from coaches, sport scientists, and physiotherapists who are devoted to building better athletes. Please take a moment to share the articles on social media, engage the authors with questions and comments below, and link to articles when appropriate if you have a blog or participate on forums of related topics. — SF