Cody sits down with good friend and private sector coach, Kyle Rogers from Seattle, Washington. Kyle own his own facility where he specializes in training baseball players from the youth level all the way up to the big leagues.

Kyle and Cody discuss how college strength and conditioning can improve with integration, how to approach programming through a skill acquisition lens, and how to allocate energy to get the most out of your training with athletes.

Connect with Kyle and Cody:

Kyle’s Media

Twitter: @KyleRogers18

Instagram: @klrogers28

Cody’s Media:

Twitter/Instagram: @clh_strength

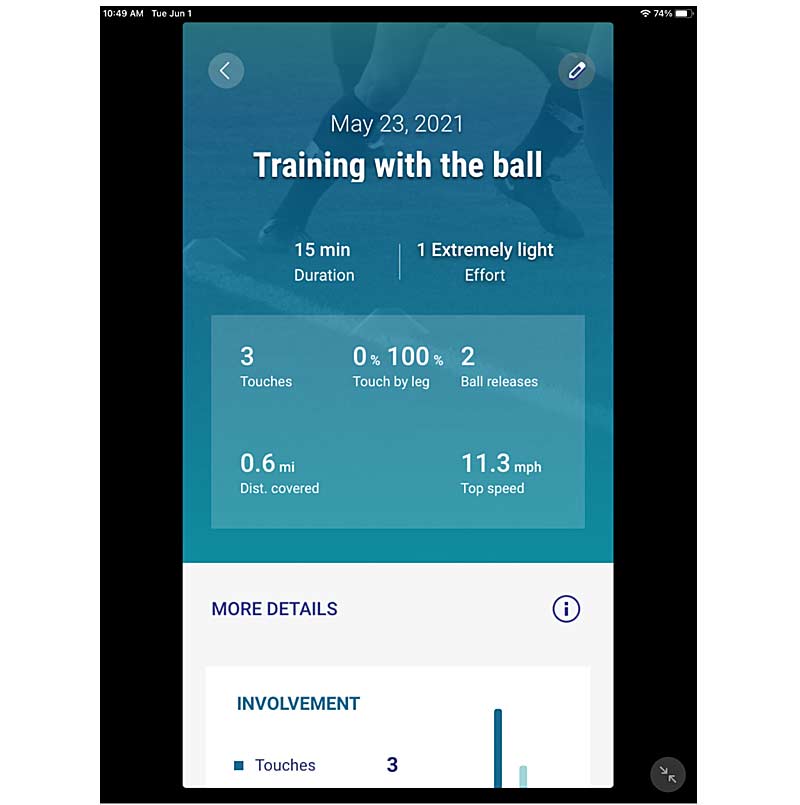

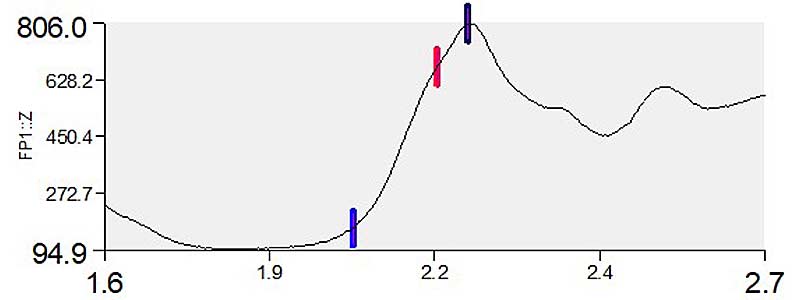

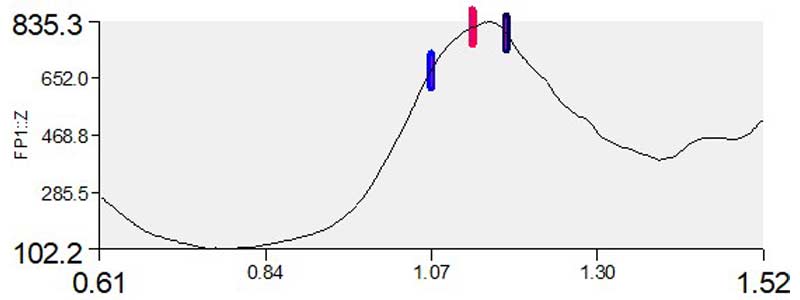

Matt Tometz is a sports performance specialist/sport science coordinator at TCBoost Sports Performance in Northbrook, Illinois. With a speed development background and a fascination for data, it’s his daily challenge to combine the art of coaching with the science of data for his athletes of all ages and sports. Outside the facility, Matt creates educational content for coaches and professionals. Find him on Instagram and Twitter @CoachBigToe, his website www.MattTometz.com, his YouTube channel and LinkedIn “Matt Tometz,” and his email:

Matt Tometz is a sports performance specialist/sport science coordinator at TCBoost Sports Performance in Northbrook, Illinois. With a speed development background and a fascination for data, it’s his daily challenge to combine the art of coaching with the science of data for his athletes of all ages and sports. Outside the facility, Matt creates educational content for coaches and professionals. Find him on Instagram and Twitter @CoachBigToe, his website www.MattTometz.com, his YouTube channel and LinkedIn “Matt Tometz,” and his email: