Many people don’t think golf is a sport, never mind that golfers need performance training or sports science. On the surface, it is hard to argue with them. In the world of golf, we don’t even use the terms “sport science” or “performance training.” For some reason, we decided to call it “golf fitness” instead.

The historically based image of golf is that of a game where people smoke and drink, and their biggest challenge is getting the club around their beer bellies. The only reason a golfer sweats is if it is hot outside. Golfers don’t even need to walk! They can just sit in a cart for the over 6 miles of course and only need to stand over their ball for 10 seconds or so at a time. They make a single swing of a stick weighing less than 2 pounds, and then get back to sitting.

Could you imagine athletes like Usain Bolt drinking a Bud Light between races? Of course not! John Daly? Of course, yes!

The golf performance training world is quite young compared to other more-established sports such as track and field, football, and basketball. When you talk to professional golfers from the ’90s, ’80s, and earlier, they will tell you that there was one Tour trailer at an event and there were more guys in there with a scotch in their hand than a weight. Then came Tiger Woods, and everything has been changing for the past 20 years.

Some Context on the History of Golf Performance

In order to understand how golf performance training has progressed to where it is today, it is important that you quickly understand how technical golf swing instruction has developed. The reason for this is because golf instruction has heavily influenced the course of golf performance over the past two decades, with the latter industry mirroring much of the former in how information was passed down.

To understand how golf performance training has progressed to where it is today, you need to understand how technical golf swing instruction has developed. Share on XThe technical side of golf (how the golf swing is taught) is entrenched in theories and the experiences of great players and great coaches. There was minimal scientific basis in much of the early teachings; rather, it was more along the lines of “a mentor taught me this way so I will teach you that way too because he worked with a great player.” Today, instruction is light years ahead of where it began, but only because there are more instructors producing scientific research and data than ever before.

The point of this digression is to demonstrate to you where instruction started and emphasize the fact that “good ol’ boy science” based on what the great players and coaches were doing was rampant in the early years, much like golf fitness.

Great golf players are determined by wins, just as in any other sport. If they won a lot and had a “good looking” swing, historically, teaching professionals would coach their amateur golfers to swing like them. This started with 2D video and has continued into the 3D kinematic and force plate kinetic worlds to an extent. Similarly, in the golf fitness world, if a winning player works out a certain way, it has often just been accepted that all golfers should be working out that way too.

Great coaches are also historically determined by wins, but not their wins—their players’ wins. If a golf coach worked with a single great player, oftentimes their career would be made, and they would be considered a great coach. More players quickly followed and their “stable” of players multiplied.

This is how many of the early golf fitness coaches and authorities came to be as well. As with the early years of instruction, little actual science or testing was done to confirm whether the majority of the methods actually worked. They were just accepted and passed down to each generation because they previously worked with great players. While that pattern is changing today in both instruction and performance, “good ol’ boy science” is not even close to extinct.

To return to the golf performance world, it all started with a number of early adopters in the golf fitness field who worked with the world’s best players. It has continued to gain steam as a legitimate field and area of expertise since. Unfortunately, the tradition of how golf instruction developed bled heavily and predominantly into the development of this field and led to a lot of bad information and poor results along the way.

Luckily, there has been a minority of sport performance coaches and scientists who actually started looking at the science and physiological demands of golf early on. They began developing the resultant training that would be required to elevate the game to where it is today.

While the minority was doing that, however, the majority of the field went with the “it has to look like a golf swing to be a golf-specific approach.” We also were drawn heavily into the idea that if an exercise is hard, it must be even better when we make it complex too. Hence, the “swing a golf club while standing on a Bosu ball” exercise was born and even featured in Golf Digest, one of the major publications in golf, with the No. 1 golfer in the world doing it.

Some of my other personal favorites include the Bulgarian split stance jumps with rotation and transverse medicine ball slam for “maximal rotational power development in your swing” or the myriad or “max strength” exercises on a physioball. But perhaps my all-time favorite is the “hold a 5-pound dumbbell in both hands and swing with the same motion as your swing to strengthen your golf swing and clear you to return to play after surgery if there is no pain.” These are unfortunately still happening today…a lot.

Forget the scientific fact that if you stand on an unstable surface, your movement recruitment and sequencing patterns totally change and you train a totally different pattern.1Forget the fact that if an exercise is too complex, you lose the ability to train maximal strength or power.2Disregard that in order to develop maximal strength, you want as little as possible of your body’s energy focused on not falling off a ball, and instead focused on exerting maximal contractile force.2The No. 1 player in the world had a golf club in his hand, was standing on a physioball, and was featured in Golf Digest doing it, so this must be the way we should train golfers.

The golf fitness industry has historically failed to accept that the only true sport-specific training is the sport itself. Share on XThe golf fitness industry has historically failed to accept that the only true sport-specific training is the sport itself. The mantra, instead, became “the more exercises we can invent that look like the golf swing, the better golfers we will produce.” While this line of thinking is slowly dying off, it is still very present in mainstream arenas such as the Golf Channel and social media. I personally can’t keep up with the number of new training devices and products that continue to come out daily from this line of thinking. Unfortunately, the average golfer is still very much drawn to the idea of “golf-ish” exercise to improve their performance.

The New Age of Golf Performance Training

As the field has matured over the past two decades and the minority has been able to educate and share their findings with more strength coaches and medical professionals, we have begun to see a shift in the field and the golf community. It’s slow, but it is shifting. Both are moving toward accepting and understanding the value of golf performance training and its importance to delivering results on the increasingly competitive and lucrative stage of golf.

Take a look on the PGA or LPGA tours and you will no longer see beer bellies as the norm, but the exception. There are now two trailers on tours, and they are busy from sunrise to sunset.

If you watch the Golf Channel whenever Dustin Johnson or Brooks Koepka play, you will undoubtedly hear comments from the commentators about their workout regimens and how “fit” they look. They will also talk about how far they can hit the ball and the new generation of golfers who are “fit and explosive.”

The reason? We are now seeing a direct correlation between how far a golfer can hit the ball and how much money they make.3

Having data showing that if you create more power, there is a correlation to making more money, aka playing better, is great! However, we are also seeing an increasing number of high-profile players who swing the club really fast getting hurt. Resiliency and longevity are starting to become higher profile concerns as the sport continues to evolve.

For golf as a larger industry, longevity should be the No. 1 concern, as the industry is combatting the baby boomer generation aging out of playing due to injury, loss of distance off the tee, and subsequent loss of enjoyment. This leads to them dropping club memberships and shifting their attention and dollars to other activities.

These elements, among others, are starting to drive an increased desire among golfers as a whole to “show me the data.” Because of this, we are in the most dangerous time for golf performance training since its inception.

Golf fitness coaches, new companies, and new products are coming out of the woodwork with the “latest and greatest” exercises and protocols to improve your golf swing speed at deafening volumes. They know golfers want to see data, so they use phrases like “we have found” and “our research shows” but there is rarely any actual research shared. Sure, they share general numbers, such as you will increase by “x” amount in your first session alone, but if you ask them to share how they found that, the science behind it, or other answers to probing questions, there will usually be crickets. If you do get a response, it is typically along the lines of “our research is proprietary.” There certainly are exceptions to this, but they are rare.

If you know a golfer, you know they will not blink at dropping hundreds or thousands of dollars on a quick fix or improvement they are told will help them play better. They also are conditioned to see a Tour player using a device or doing an exercise and immediately think they should be doing that too. Put these two things together with deceptive data marketing and you have a recipe for poor outcomes based on “good ol’ boy science” and the potential for easy money.

The Science Behind Golf Performance Training

The ultimate sport-specific expression of power in golf is club head speed. Every mph increase a golfer is able to achieve with their swing speed equates to just about 3 yards of added distance, assuming similar launch conditions.4

The average elite golfer age 17-30 swings the golf club at 113 mph.5The length of time it takes their downswing to accelerate from 0 mph to 113 mph is under 1 second, and this is only the 50th percentile. From our research here at Par4Success, of over 600 data points, the 90th percentile is above 120 mph.5We have compiled percentiles for all ages/sexes, and all of these numbers are available at our website for free if you are interested in how speeds change over life and development.5

Golf is an anaerobically driven sport with incredible accelerations and max speed and 3-5 minutes on average between swings in competition, depending on pace of play. Hip rotational speeds on the PGA Tour are around 600 degrees per second, torso rotational numbers are in the 800 degrees per second range, and hand speeds are in the 1500 degree per second range or more.

The best players on Tour are some of the most explosive rotational athletes on the planet. What increases their need for solid strength and conditioning is that they have to do it week in and week out, playing 5-6 days per week during a season that spans over 11 months! It also includes travel around the world, which makes recovery and resiliency a huge issue as their “off” days are more often than not spent traveling to the next event.

The four elements that influence how fast a golfer will swing are equipment optimization, technical efficiency, mobility, and power. Share on XThere are four elements that need to be considered that influence how fast a golfer will swing. The first two are outside the realm of strength and conditioning: equipment optimization and technical efficiency. The second two that need to be considered are mobility and power.

Mobility in Golf

Mobility for golf can be quite complex if you get into the weeds of wrist angles, elbows, etc. At a minimum, you should look at the overall athletic movement competency of your golfer.

Whatever your preferred system is doesn’t matter to me, just have one. It could be a formal system such as the SFMA or just generally looking at squatting, hinging, and overhead mobility. I honestly couldn’t care less what you use, but please have a system to consistently assess and objectively place your athlete at a starting point. This is a critical step that gains you an understanding of where your performance plan needs to start.

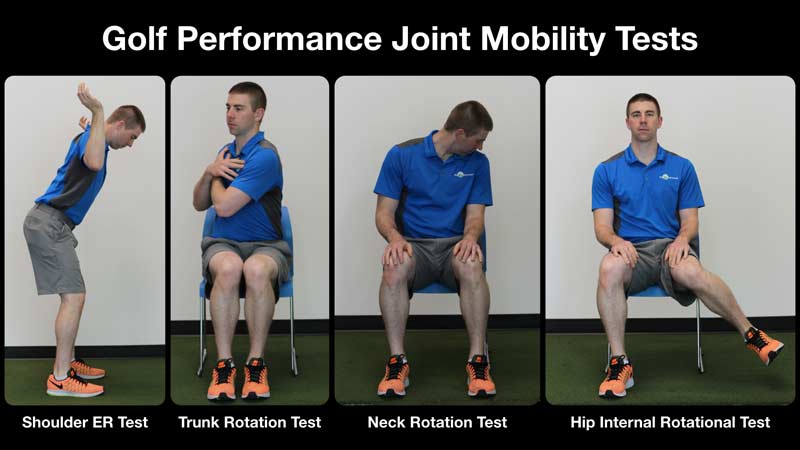

Look at the overall athletic movement competency of your golfer. Look at the critical rotary centers: hip internal, thoracic, shoulder external, and neck rotations. Share on XWhat I do care about, however, is that you look at the critical rotary centers of your golfer. The areas of rotation can be condensed into four main centers: hip internal rotation, thoracic rotation, shoulder external rotation, and neck rotation. Any limitation in one of these areas leads to unwanted lateral movement and loss of posture in the golf swing.

A decrease in internal rotation of the lead hip in a golfer is highly correlated to low back pain.6,7The fact that more than 50% of golfers experience back pain at any given time makes it the most common injury in golf.7In our clinic, we have also seen limitations in any of the rotary centers lead to technical compensation and injury in other parts of the body that end up taking up the slack.

One recent example in a golfer was an injury to the lead hand thumb at transition. This was due to limited trail arm shoulder external rotation and thoracic rotation to the trail side. It ended up placing increased stress on the lead hand thumb. The added stress ultimately led to injury, as well as decreased distance and accuracy. We also noted a significantly weaker grip strength on the lead side. This suggested decreased resilience to the vibratory stresses experienced during impact, likely also contributing to the injury.

Once the trail arm shoulder external rotation and thoracic rotation were fixed, the thumb was treated locally, and the decreased grip strength was trained up. We ended up seeing an increase in speed compared to prior to injury and an increase in accuracy without any future return of the injury.

Golfers need competency in all four rotary centers. If competency doesn’t exist, the compensations they have to make often lead to decreased performance and injury. Share on XThis example illustrates perfectly the importance of competency in all four rotary centers. If that competency does not exist, the compensations that will have to be made often lead to decreased performance and injury. It is very common in golf for a back injury, the most common injury in the game, to be caused by a lack of rotation in one of the four centers.

Identifying a fail is the first step, but the real impact will be made by determining why the fail is occurring. Identifying why allows you to quickly implement positive change and deliver improved results. When you are successful with this, you will see positive changes in the golfer from not only a power perspective, but also a longevity one.

Power in Golf

Creating power in golf boils down to the same physiological requirements as any other sport: how much force the golfer can create and how quickly they can deliver it. At Par4Success, our questions initially centered around figuring out what types of movements were most important for golfers to develop power in. This led to a three-year-plus study looking at 600+ data points to determine which tests would correlate most highly to club head speed with golfers.

Figure 1 shows the three power tests and the anti-rotational test that we found to have high correlations to club head speed. It is important to note that the table of 600+ data points is for golfers ages 10-70. Do not take this overall table to be reflective of all golfers at all ages, as there were stark differences within the age brackets and the corresponding r-values.

We have broken down the correlations by age brackets for more age-reflective and actionable data in our full research report and noted a significant change in each test’s r-value based on the age and developmental level of the player.5I would encourage you to look at the full report if you work with golfers and/or are interested in how the r-value for each value changed in relation to the age of the athlete.

| Sample Size | Vertical Jump | Seated Chest Pass | Shotput R | Shotput L | Keiser R | Keiser L | Height | Weight |

| 618 | 0.643 | 0.793 | 0.810 | 0.805 | 0.537 | 0.574 | 0.722 | 0.626 |

Figure 1. Par4Success conducted a 3+ year study looking at 600+ data points to determine which tests correlated most highly to club head speed with golfers. This table shows the four tests—three power and one anti-rotational—that we found to have high correlations to club head speed. (Note: The table is for golfers ages 10-70. Do not take this overall table to be reflective of all golfers at all ages, as there were stark differences within the age brackets and the corresponding r-values.)

As evidenced by the data, it is critically important to train golfers as a whole to be able to express power in ways that would improve performance in these tests (vertical, linear, horizontal, and rotational force generation). What this means is that as coaches, we need to assess where a player lacks power creation and work to train those areas up without neglecting to continue to improve their strengths.

As coaches, we need to assess where a player lacks power creation and work to train those areas up while continuing to improve their strengths. #golf Share on XI want to be clear that this data does not mean that we should train the specific tests, however. In fact, we rarely have our athletes do any of these tests in their actual training programs. Instead, we train the strength, speed, and skills required in the sport of golf as demonstrated by these tests.

How to train power is very well-researched in other sports and needs to be looked at and understood by any coach deciding to work with golfers. A player’s location on the speed-strength continuum, their training age, their goals, and even what they will be able to accomplish genetically should all be considered.

I believe it is also critically important to the development of golfers that we base our training systems, particularly with our elite athletes, on the science around peak power production such as the incorporation of Olympic lifts. Unfortunately, incredibly popular but unproven training ideas dominate the golf fitness world (i.e., throwing a 6-pound medicine ball against a wall will produce insanely powerful and resilient golfers).

Traditional and proven methods are more often the best option to train power than the new shiny thing that caught your attention or the movement that looks like the golf swing. But if the new shiny thing ends up being proven, don’t be close-minded and refuse to try it.

The Future of Golf Performance

The future of golf performance lies in my above statement. We need to prove that the traditional golf fitness methods we use really produce meaningful performance gains. When doing this, we need to challenge the traditional methods at a scientific level, not a case-by-case level, to determine which produces better performance objectively. Progress needs to be rooted in the true sports science of power and speed development without ever losing sight of the importance of empirical evidence.

The future needs to be wary of new methods and products with bold claims but unshared proprietary data. Traditional methods that fall short in quantitative results must be reconsidered. We need to focus on asking ourselves: How do we really know this works, and how do we know this is the most efficient way to achieve our goal? Is it because science showed us or because “x” expert or professional said so? The future is in researching and proving that what we are doing works.

Progress in golf performance must be rooted in the sports science of power and speed development without losing sight of the importance of empirical evidence. Share on XFor instance, we ran a small 20-golfer preliminary study in 2018, looking at the effect different types of rotary training might have on club head speed. We compared Exxentric’s kPulley eccentric flywheel to traditional bands and cable machines (the accepted industry norm) and saw some interesting results. We found double the increase in club head speed when utilizing eccentric flywheel rotational training compared to bands and cable machines over a six-week period. This should lead to questions of potentially more efficient rotary power training.

We also took a look at the incredibly popular overspeed training phenomenon that is helping golfers across the globe increase their swing speed. The system utilizes a 20% lighter club, a 10% lighter club, and a 5% heavier club. We assessed kinematic data with each of the clubs and also looked at a 66% lower training volume protocol to see what it would bear.

Our initial study of just over 20 golfers showed undesirable kinematic sequence changes with the 20% lighter club. It also demonstrated almost double the club head speed improvement with the lower volume protocol. This suggests only using the single 10% lighter stick, while requiring strict rest-to-work ratios adhering to glycolytic recovery needs to assure quality of repetitions, might be a more-efficient and more-effective training option.8

This study led us to do a follow-up study, which we are currently in the middle of. The initial study only spawned more questions as to the most effective ways to impact positive speed improvements.

Another one of our studies over three years looked at the relative benefit of triphasic training versus traditionally periodized training (higher reps with lower weight progressing to lower reps with higher weights) on club head speed in different age groups. We noted that traditional training produced a 50% greater increase in clubhead speed in juniors (10-16 years old) relative to the expected 12-week average.5

Comparatively, traditional training produced a 10% worse result in adults 50 and older. We essentially saw the inverse results with triphasic training relative to each group.5The numbers in this study are quite a bit larger and therefore more easily expandable, but nonetheless, my hope is that this sparks follow-ups and future research into the area of golf performance.

These are just three examples of the studies we have completed in an effort to put some publicly available information and data behind what golfers are doing and be able to show them why. In the coming years, the idea that kinetic sequencing and power profiles for each specific player can maximize training program effectiveness will likely emerge. This might be based on what some would call a golfer’s “swing DNA,” and we could then look to develop training protocols to support the kinetic forces they most utilize in their swing. Theoretically, it makes a ton of sense, but we will have to wait and see if it pans out.

As we push forward in the golf performance industry, we need to continue an incredible emphasis on meaningful data. Share on XTo wrap up, the golf fitness industry has turned into the golf performance industry on the backs of some insanely smart and driven individuals early on. While we are a heck of a lot further into the realm of sports science and data-driven performance results than when we started, we still have a long way to go.

We need to display the discipline and drive to continue to push forward with incredible emphasis on meaningful data. The greatest thing I can hope for 20 years from now is for someone to send me this article and tell me that I was dead wrong on every single point I brought up. The email would come attached with all of the data from their research proving me wrong. That would be a great day for the world of golf and golf performance!

Since you’re here…

…we have a small favor to ask. More people are reading SimpliFaster than ever, and each week we bring you compelling content from coaches, sport scientists, and physiotherapists who are devoted to building better athletes. Please take a moment to share the articles on social media, engage the authors with questions and comments below, and link to articles when appropriate if you have a blog or participate on forums of related topics. — SF

References

1. Sternlicht, E., et al. “EMG Comparison of a Stability Ball Crunch with a Traditional Crunch.”Journal of Strength and Conditioning Research. 2007;21(2):506-509.

2. Cressey, E.M., et al. “The Effects of Ten Weeks of Lower Body Unstable Surface Training on Markers of Athletic Performance.” Journal of Strength and Conditioning Research. 2007;21(2):561-567.

3. Dusek, David. “By the Numbers: Distance Off the Tee Really Does Pay Dividends.” Golf Week. 4/22/18.

4. Tutelman, Dave. “What Is a MPH of Clubhead Speed Worth?” Swingman Golf. 7/7/15.

5. Par4Success Public Research Data.

6. Vad, V.B., et al. “Low Back Pain in Professional Golfers: The Role of Associated Hip and Low Back Range-of-Motion Deficits.” American Journal of Sports Medicine. 2004;32(2):494-497.

7. Murray, E., et al. “The relationship between hip rotation range of movement and low back pain prevalence in amateur golfers: An observational study.” Physical Therapy in Sport. 2009;10(4);131-135.

8. Prengle, B. Cassella, A. Finn, C. Graham, T. “The Effects of Reduced Overspeed Protocol Volume on Club Head Speed in Golfers – A 6-Week Study.” 10/18.

Hi Chris,

Great article. Thanks for your work.

Question for you concerning your findings using the kpulley… where/what did you find was the biggest improvement? Was it the golfers’ abilities to accept force, control it better because of the eccentric overload created by the k pulley? So therefore more capacity to regenerate it? Or was it something else?

Did you try a bigger sample size? With more athletes? Was this done with beginner level gym going golfers? You think it would work as well with golfers that have more loading experience?

Thanks for your time

JC

Thanks for reading the article JC and for the great questions. The biggest metric we were measuring was the end result of club head speed. I would tend to lean towards you being correct that the golfers improved their ability to absorb, transfer and then express the power better through the phases of movement. This was done with a group of golfers with handicaps ranging from 1 – 24, yes I believe it would be beneficial on golfers with more loading experience in general. We are looking at increasing our future sample sizes as well for sure.

Chris,

With our electronic world its easy to get side tracked.

Trying to get my gym to consider a K pully.

Thanks for keeping me on track.

gm

Does anyone have a basic set of must stretches, must strength, must core, etc. Exercises that a golfer should be doing constantly