Anna Woods is a wife and mom to three children in central Kansas. She earned her degree in Exercise Science with a minor in marketing in 2005. Her credentials include: ACE-CPT, Biomechanical Exercise Specialist, CF-L1, DNS Running/Weight Training/Exercise 1, Functional Aging Specialist, PFP-Personal Trainer of the Year Finalist (2017), Metabolic Flexibility Certified.

She has been in the fitness industry for over 16 years and currently is the CEO and Founder of sheSTRENGTH, an online and in-person fitness and training program. She trains women and youth of all abilities in her barn gym behind their home in rural Kansas. Additionally, she is the strength and conditioning coach for the Hutchinson Community College Blue Dragon NJCAA softball team and she works with many softball players in the area. Anna is also the author of the soon-to-be released book and CEU course “Adaptive Fitness Exercise Specialist,” which trains coaches, teachers, and trainers on how to work with athletes with special needs/accommodations.

Freelap USA: Breaking technical movements into constituent parts is a common process in skills training for team sports—how do you use this same concept to “reverse-engineer” Olympic lifts and teach youth athletes how to begin getting into foundational positions that will support the full movement?

Anna Woods: As an athlete myself, I have had the huge honor to train under the mentorship of multiple high-level Olympic lifting coaches over the years and I’ve taken various cues they’ve given me and tried to apply them in practical ways for my athletes to understand. The late Glenn Pendlay always taught the clean from the top down, and I applied this same concept to my teaching methods.

I like using medicine balls to break down the clean positions for many reasons:

- Because we have a smaller gym with limited access to barbells.

- A medicine ball is less intimidating, which allows the athlete to relax and not overthink all the steps to completing a clean.

- More athletes can go at one time, which is great for large-group or team settings.

One of my favorite top-to-bottom clean position drills is “beat the ball to the floor.” Athletes stand arms-width apart from each other, both hands on a medicine ball, with arms extended out straight at hip-height. The athlete going first stretches up on her toes and extends her hips fully toward the ball. Both athletes then count to three, and on three, one athlete drops down under the ball into a squat catching the ball in a front-rack position with their feet flat on the floor.

Video 1. Playing “Beat the Ball to the Floor” game to teach basic positions of the clean.

The second pull of the clean is the hardest to teach, so again, trying to keep the drills less technical and intimidating, we use medicine balls for this as well. This is the most impactful portion of the lift in its carryover to power and hip drive in other sports—yet it is the part of the clean that is bypassed by most athletes.

For the next drill, both partners stand apart from each other: one partner will be on the floor, kneeling back on their heels and holding the medicine ball out front of their body (and I like to have my athletes elevated on a mat with their feet hanging off the back for this position, because many lack the ankle dorsiflexion to kneel all the way back). The partner on the floor violently extends their hips up and forward to drive the medicine ball up and out toward their partner, who is standing a few feet away and waiting to catch the ball.

The only cues I provide are that the arms should stay long and loose and cannot extend away from the body before the hips are fully extended. Sometimes, we will even place bands under the athlete’s armpits and I tell them the bands can’t fall out until the ball is released out of their hands. This forces the ball to be tossed up in the air using only hip drive, not arms or traps.

Video 2. Partner medicine ball exercise to teach the feel of the second pull of the clean.

From here, we will transfer these same drills to a PVC pipe or lighter barbell and continue with drills like the “rocking chair” as I like to call it. For this, I have my athletes stand in front of a tall box. Again, focusing on the second pull of the clean, I have them start with their back toward the box in a hang clean position, with their chest over the bar and knees slightly bent.

I cue the athlete to pull their chest behind the bar to slide the bar up their thighs, and as they pull their chest behind the barbell, they sit back on a high box to feel the load of the bar in the mid-foot and heel. After the chest has passed behind the barbell, the athlete then violently stands up, driving their feet into the floor as they extend their hips upward and out to maneuver the bar up to the shoulders in a front position.

Video 3. “Rocking Chair” clean drill with a box.

We will practice one or two of these positions as foundations to learning the clean the first month, then we progress to using barbells or dumbbells mostly, and only use these drills as part of our warm-up prep for lifting that day.

Freelap USA: Softball is a rare sport in that playing the game doesn’t necessarily improve the main physical qualities that most impact the game. How do you approach performance training to improve physical KPIs for softball, particularly with year-round players who have demanding game and practice loads?

Anna Woods: My approach to the performance training side of softball is very intuitive and based on a weekly assessment of workloads for the athletes I work with. For the college team, I have 3 different templates I will work from each workout session, depending on the week’s workload in terms of practices and games. The three templates vary in intensity, volume, and recovery—depending on that, we will choose one of the templates to work from.

My goal with these movements for corrective exercise is to stay on top of building and maintaining good patterns in throwing, hitting, and pitching, says @SheStrength. Share on XA common denominator for all three templates includes long warm-ups and cooldowns, with a lot of soft tissue work, breathwork in various positions, t-spine mobility, pelvis control for hamstring length, and anti-rotation/rotation patterning. Our sessions typically last no longer than 45-60 minutes, 2-3 days a week. My goal with these movements for corrective exercise is to stay on top of building and maintaining good patterns in throwing, hitting, and pitching. Bad habits sneak into these technical movements so easily, so we do our best to create opportunities to slow down and reintegrate good movements—specifically with rotation—into our lifting sessions.

After re-patterning good movement back into the body, we will work to add load and intensity at various levels to build strength and power. We saw this carry over into the performance of our athletes last year in terms of avoiding injury—we had only one hamstring strain all year, and that was related to a fluke accident.

Video 4. Before vs. After of addressing this pattern of low back extension and one way we correct it.

We also spend a lot of time working foot load and rotation in our pre-lifting skill work with the use of bands. And lastly, for strength, we focus on working antagonist muscles that are overused in their year-long seasons. This is where the use of TRX and light bands/dumbbell work comes into play. Again, everything we do is focused on creating efficient patterns of movement to avoid bad habits and injury.

For conditioning, we focus mostly on energy system development based on the position played. But in general, most days will include team competitions, EMOM’s, assault bike all-out efforts of 4-6 seconds, or sprints with acceleration and deceleration. It looks something like:

- (5-8 Min) Soft Tissue Work: Foam rolling, lacrosse ball focus on shoulders, lats, bottom of the feet.

- (8-10 Min) Corrective: Thread the needle, foot wringing, big toe mobility, hip flexor stretches, tripod rocking, adductor rocking, Dynamic Neuromuscular Stability Development positions (6-10 mos).

- (5 Min) Postural: Deadbug, bird dog, Paloff presses in half-kneeling, lazy squat holds, single leg squat holds, deadlift holds with breathwork.

- (30-35 Min) Lifting: Deadlift variations, split squats, pulling, rowing, landmine press, internal/external shoulder rotation.

- (10-15 Min) Power/Skill/Conditioning: Agility ladders, Medicine ball drills, team relays, sprints, plyometrics, box jumps, banded runs.

- (5 Min): Breathwork, mindset, soft tissue work, DNS re-patterning.

Freelap USA: Softball is also highly asymmetrical with stress on one throwing arm, one drive leg, and in most cases one swing pattern. Do you target those specific imbalances in performance training for softball, either to mitigate or to accentuate the effects of those repeated actions?

Anna Woods: I spend a lot more time working on this with my pitching athletes. Many go to pitching lessons and work on speed, spins, and power, but spend little time slowing the motions down and learning to activate the big-toe/glute with take off, how to “feel” the oblique’s load and stretch through the middle of the pitch, and how to drive through a strong front leg and foot load.

Most of my time is probably spent learning how to teach the athletes to truly rotate. I have had the pleasure of working under the guidance of Dr. Jared Shoemaker, DC at InMotion Spine Muscle Joint and he has helped me learn how to break down true rotation through the mid-back and obliques and teach it in small pieces to our athletes. Many athletes I assess will overcompensate true rotation by leaning to the side, overthrowing with anterior delt and bicep, extending through the low back, clenching through the neck and teeth, and overusing the hip flexor of the drag leg.

When the athlete is forced to slow down and work through these compensations, she will begin to feel the difference between rotation and overcompensation and retrain the tissues to work correctly, says @SheStrength. Share on XWhen the athlete is forced to slow down and work through these compensations, she will begin to feel the difference between rotation and overcompensation and retrain the tissues to work correctly.

My favorite ways to train this are:

- Banded single-arm rotation with ball.

- Paloff anti-rotation in kneeling, half-kneeling, lazy squat (stick across back of shoulders).

- Hanging stance with ball.

- 3-Mos to low oblique sit.

Video 5. Here I am tactile-cueing an athlete to rotation through her mid-back using the stick as a guide.

Freelap USA: After being forced to utilize remote coaching methods during the pandemic, many coaches have realized this is a sustainable model for training a broader base of athletes. What do you think are a few of the keys to executing a viable and effective remote coaching program?

Anna Woods: The main way I have learned to execute an effective remote coaching program is to try to maintain as much of the culture of in-person training as you can via an online community. Some of the best ways I have figured out how to do that include:

- Creating team competitions within the group.

- Making social media challenges.

- Sharing videos of my own workouts or sharing personal struggles.

- Asking guests to drop a line or two in the group as motivation.

- Delegating team captains or leaders in the group to lead conversations in the message boxes.

I require daily accountability and post check-ins on each day’s workouts as part of the points system we use in team competitions, which drives others to get their workouts completed. I keep workouts simple and repetitive for 4-5 weeks, and include videos to follow along with. I record workouts we do as a team at every session and load those videos to YouTube so I don’t have to spend a lot of extra time making videos for athletes to follow during remote coaching times.

The main way I have learned to execute an effective remote coaching program is to try to maintain as much of the culture of in-person training as you can via an online community, says @SheStrength. Share on XFreelap USA: You also work with clients who have special needs or who have suffered a serious injury. For those athletes who may not have clearly defined fitness or performance goals, what are the first steps for creating motivation and buy-in, and how do you individualize your programming to meet their needs?

Anna Woods: I have worked with athletes with special needs for 14 years and I have to say every client I work with is motivated differently—so that is a hard question to answer, because each client has his or her own motivations and needs.

In general, my clients who use wheelchairs or are non-ambulatory have goals that include maintaining independence for as long as possible. This includes being able to transfer themselves out of the wheelchair, having strength to drive a car, maintaining arm strength to manually wheel across terrain or up and down ramps in public places. Many also want to keep their weight down and continue to fit in their wheelchairs. Most people in wheelchairs only receive a new wheelchair every 5 years, so maintaining weight and strength is important to keep good posture in a chair over a 5-year span.

In general, my clients who use wheelchairs or are non-ambulatory have goals that include maintaining independence for as long as possible, says @SheStrength. Share on XMore ambulatory clients, such as people with ASD, Down syndrome, or other diagnoses have motivations to look like certain celebrities, to fit in certain clothes, or to look good in front of others. Their goals are similar to any other clients. Those that compete in Special Olympics or other athletic sports also want to get faster, stronger, and more athletic for their events—and parents and caregivers want the athlete to avoid injury as much as possible, so strength training and conditioning are of great assistance. The buy-in usually must be created with the parent or caregiver of a person with special needs, because so much of the life of a person with special needs is avoiding injury, disease, or pain—so the idea of weight training can be scary for most.

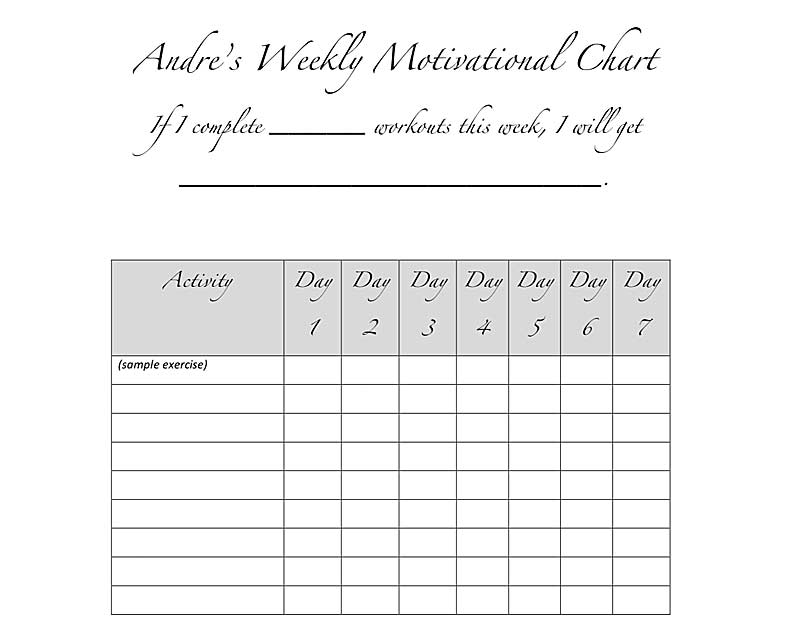

Great first steps to create buy-in include having a sit-down meeting to go over goals, address concerns, and understand triggers/struggles, fears, or anxiety the parent or client may have. Secondly, the coach should be prepared to demonstrate a few exercises to ease the concern of all involved. Positive reinforcement through reward charts, non-food reward goal lists, and daily, weekly, and monthly challenges help the person with special needs stay motivated.

Most athletes with special needs are underestimated in their abilities and strength, when they have more grit and determination than the most talented athletes in the program. Many can do similar movements as the other athletes in the group, they just may need slower directions and a visual cue to follow along with. Those in wheelchairs may need to use PVC pipes instead of barbells or may need hand attachments for bands because of limited grip strength, but in general, the programming is the same. For conditioning, I will have my non-ambulatory clients be timers or rep counters for those conditioning if it’s a movement they cannot complete, so they are still engaged and a part of the group.

Video 6. Air Assault Bike adapted exercise.

Communication is also different for people with special needs. For some diagnoses, like ASD or Down Syndrome—time is typically not a motivating factor to increased effort, so goals that are task-based seem to be more effective. Instead of saying do as many reps as you can in 30 seconds, tell the client they have to do 20 reps before they get to put the dumbbells down. Or for walking/running/rolling exercises, place manipulatives such as cones on the floor for each station or targeted distance instead of using time descriptions.

Since you’re here…

…we have a small favor to ask. More people are reading SimpliFaster than ever, and each week we bring you compelling content from coaches, sport scientists, and physiotherapists who are devoted to building better athletes. Please take a moment to share the articles on social media, engage the authors with questions and comments below, and link to articles when appropriate if you have a blog or participate on forums of related topics. — SF