In August of 2015, the NCAA enacted legislation requiring all Division I full-time strength and conditioning coaches to be certified by an accredited certification body. This legislation has since prompted high school athletic directors to require that high school strength and conditioning coaches also obtain certification from an accredited organization.

This is significant for coaches, because there are numerous certifications out there that are not from an accredited certification body and it is very important for coaches entering the field to have an understanding of what they will need in order to obtain the positions they are applying for as strength and conditioning coaches. This article will give young S&C coaches—and even older coaches—the information they need to make good decisions when it comes to obtaining valuable certifications.

Because there are numerous certifications out there that are not from an accredited certification body, it is very important for coaches entering the S&C field to have an understanding of what they will need, says @DrRaymondTucker. Share on XThe two most popular accredited certification bodies for strength and conditioning are the National Strength and Conditioning Association (NSCA) and the Collegiate Strength and Conditioning Coaches Association (CSCCa). The NSCA offers the Certified Strength and Conditioning Specialist (CSCS) certification, while the CSCCa provides the Strength and Conditioning Coach Certified (SCCC) certification. The key difference between these two certifications is that obtaining the SCCC requires candidates to complete a 640-hour, hands-on practical internship under the supervision of an SCCC-certified strength and conditioning coach and pass a written exam. In contrast, the CSCS certification can be attained simply by passing the certification exam, without the same requirement for practical experience.

Certifications & Career Opportunities

Employment opportunities at the high school, collegiate, and professional levels typically require coaches to hold either the Certified Strength and Conditioning Specialist (CSCS) or the Strength and Conditioning Coach Certified (SCCC) certification before applying. Over the years, many coaches who are experts in strength and conditioning have created and developed the curriculum in these certification courses. These courses are based on those expert coaches’ extensive training, education, contributions to training methodologies that improve athletic performance.

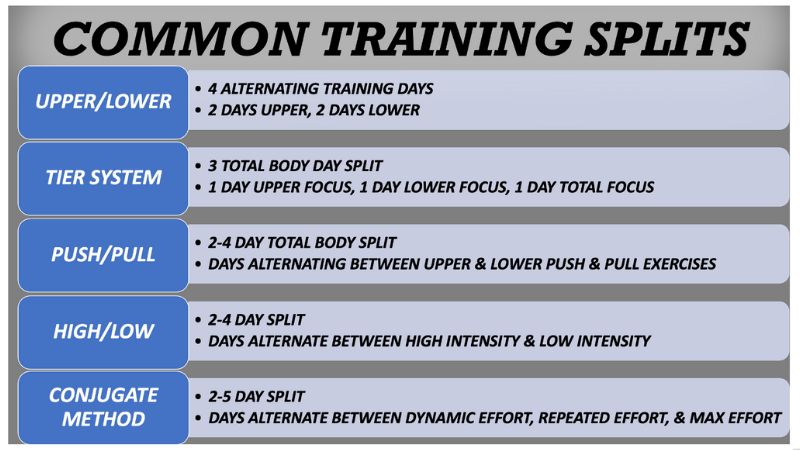

The CSCS and SCCC certification textbooks and resources will educate you, and the exam will test your ability to apply theory and scientific knowledge to reduce the chance of injury and improve athletic performance. One of the drawbacks of the CSCS and SCCC is that they do not really teach you a system of training that you can implement with your athletes or clients.

Athletic administrators, however, view the CSCS and the SCCC as the gold standards of strength and conditioning. One of the distinguishing factors between the two is that the CSCS is geared toward any coach or personal trainer who wants to get certified as a strength and conditioning coach. The SCCC, meanwhile, is geared specifically to those individuals seeking a career as a collegiate strength and conditioning coach. Also, the CSCCa is a practical program that gives coaches an opportunity to learn by conducting strength assessments in real time and you will be provided instruction by a certified collegiate coach who is experienced in training elite groups of athletes on a daily basis.

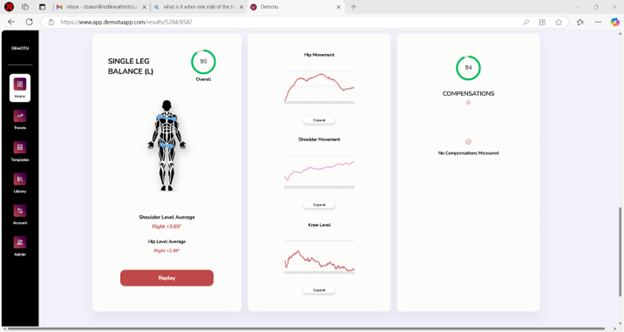

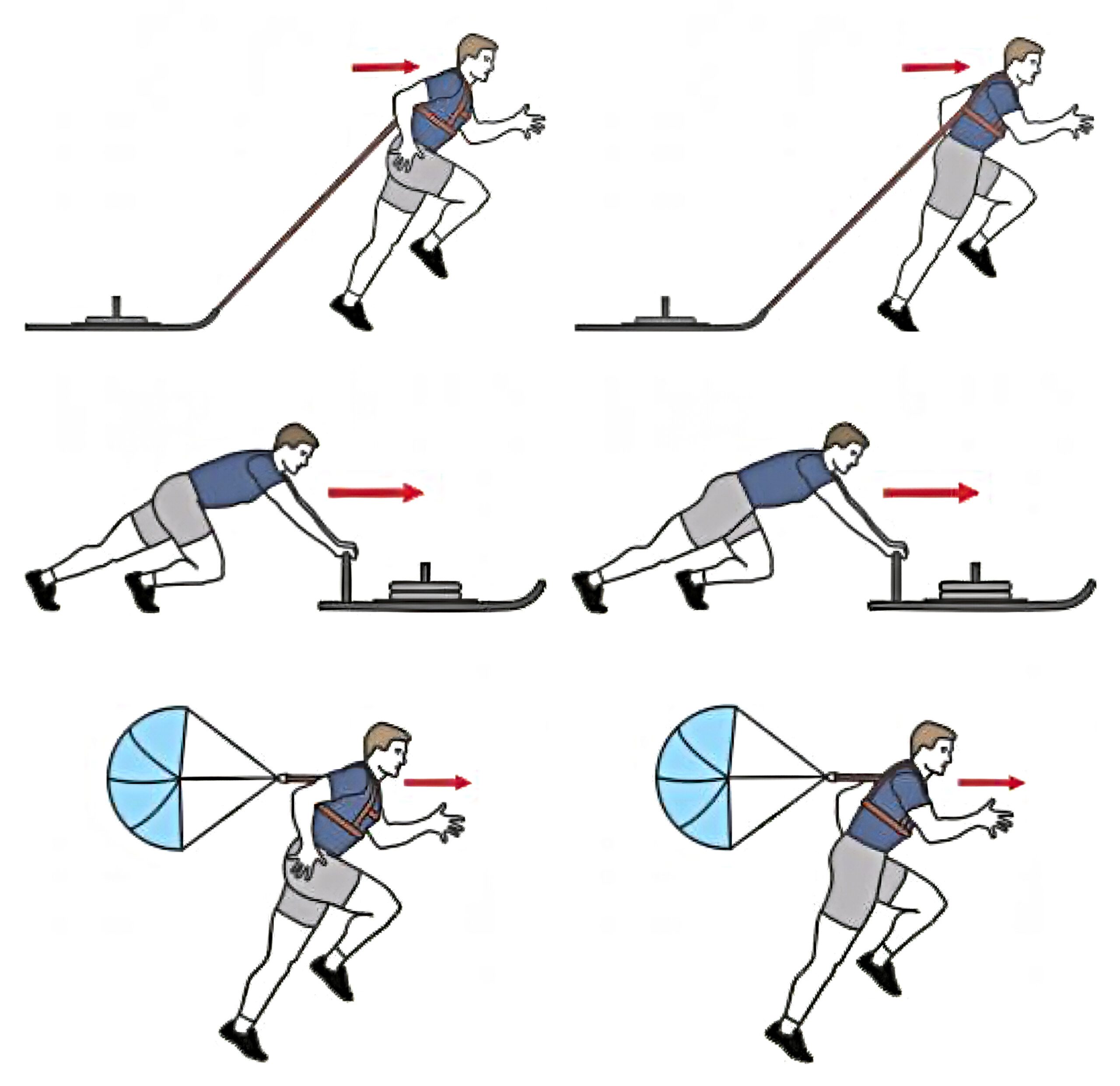

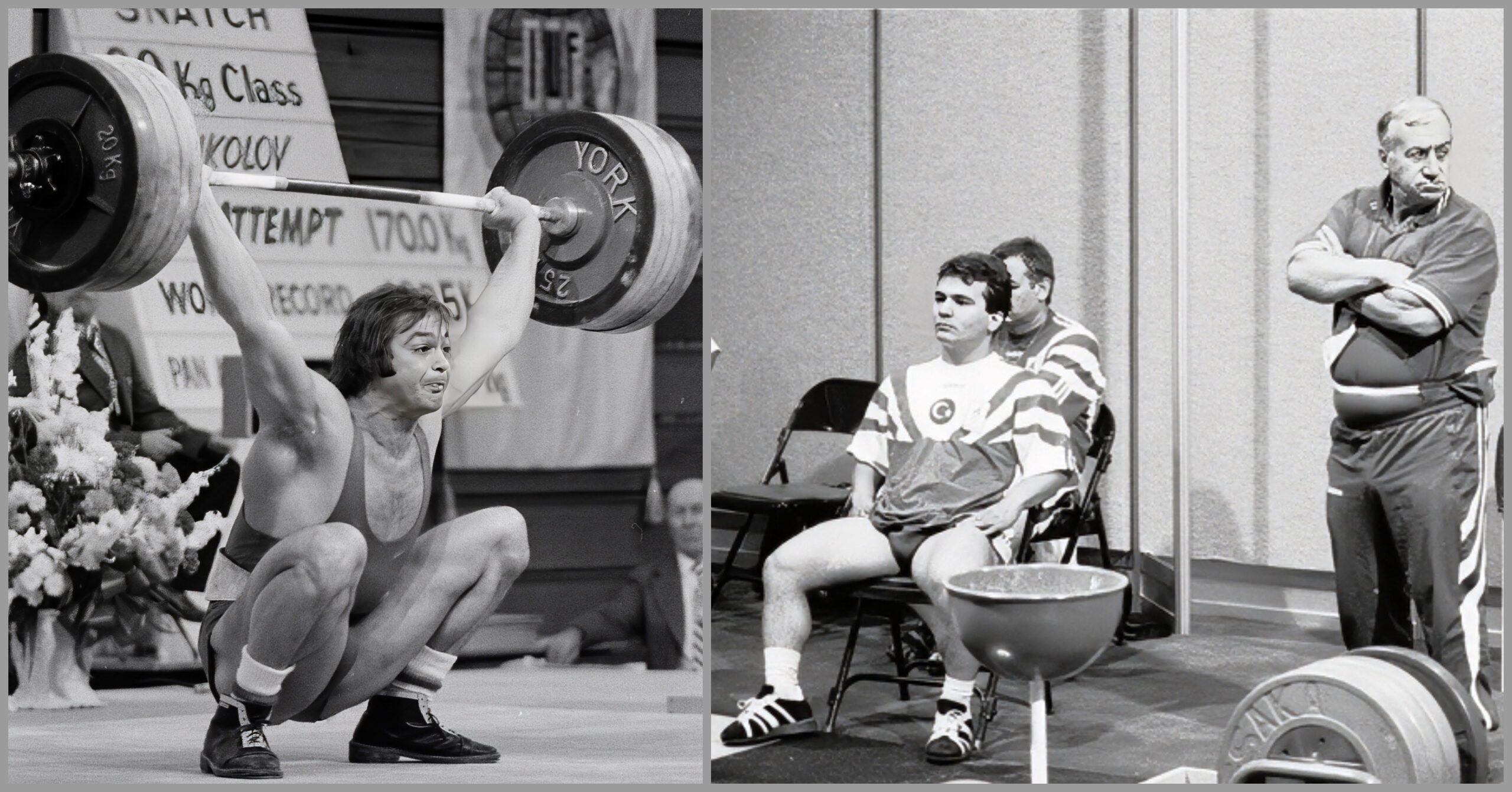

One of the distinguishing factors between the CSCS & SCCC is that the CSCS is geared toward any coach or personal trainer who wants to get certified as a strength and conditioning coach, says @DrRaymondTucker. Share on XThere are many excellent strength and conditioning certification courses available that provide a clear blueprint and a training system you can use with your athletes after completing the course. One certification that has gained popularity worldwide is the Certified Functional Strength Coach (CFSC) Level 1 and 2, offered by Coach Michael Boyle at MBSC. Another quality certification is the EXOS-XPS Performance Specialist Certification. If a coach wanted to learn more about speed and multidirectional training, Coach Lee Taft has several good certification courses and ALTIS education has several courses such as the foundation course and the short sprint courses. Finally, if a coach wanted to learn more about Olympic weightlifting, the USAW L1 and L2 courses are second to none and the majority of the coaches in the field of strength and conditioning have taken one or both of these courses.

While several certifications teach you how to incorporate various tools and methods into your strength and conditioning program—such as the Vertimax, kettlebells, TRX, and Dynamax—coaches need to understand that these are merely training tools and methods, not an entire training system.

As a coach or member of a coaching staff, it’s crucial to determine how these training methods fit into your overall training approach. Unfortunately, many coaches in the industry become certified in these specific methods and end up basing their entire training system around them. Coaches need to remember that these companies aim to educate you on a training method, while also promoting their products. The rest of this article will focus on three of the common questions asked by young coaches entering the field, with an answer that will provide some guidance in helping to make the right decision.

Question A: “Do I need certifications?”

The answer to the question is yes. Administrators at various levels have required coaches to have either the CSCS or SCCC certification to even be considered for an interview. In some cases, they may even ask candidates to submit a video of them coaching various exercises to evaluate their coaching skills.

Most coaches who are interested in careers in strength and conditioning prefer the SCCC certification due to the internship requirement, which must be completed under a certified strength and conditioning coach. This internship is an excellent opportunity for any coach, as you will be introduced to a training system. The internship would also connect you to other industry coaches and allow you to network with other professionals.

Question B: “What other certifications do I need to complete to make myself more marketable?”

As young coaches entering the field of strength and conditioning, many of us have mistakenly pursued one certification after another in hopes that these credentials would enhance our marketability and lead to job opportunities. Some experienced strength and conditioning coaches in the profession, who may not hold numerous certifications, often joke about those who list various credentials after their names, referring to it as “chasing alphabets” or “alphabet soup.”

There are both pros and cons to obtaining multiple certifications.

On the positive side, if you’re older or have a busy lifestyle, you might find it challenging to quit your job for an internship, or you may lack the time or resources to travel, meet coaches, or attend conferences. In such cases, enrolling in a certification course can be a valuable experience, offering you access to educational material you can review and continue to learn whenever you need it. On the negative side, they can be quite expensive, and some certifications may overlap with others you have already obtained. Some courses may not meet your educational expectations, and some require an annual renewal fee.

On the negative side, courses can be quite expensive, and some certifications may overlap with others you have already obtained. Some courses may not meet your educational expectations, and some require an annual renewal fee. Share on X

Several years ago, there was only one certification in the strength and conditioning profession: the CSCS offered by the NSCA. The purpose of obtaining this certification was to demonstrate that individuals had acquired and understood the scientific knowledge necessary to reduce the risk of injury and improve athletic performance. Since this was the first strength and conditioning certification for coaches, it was considered to be the gold standard for hiring strength and conditioning coaches across various levels, from high school to collegiate and professional sports.

Over the years, several other certifications in strength and conditioning have emerged, allowing coaches to deepen their knowledge in different areas. Some coaches who have completed these various certification courses often add these credentials to the end of their names as a symbol of accomplishment and dedication to their education, enhancing their skills as coaches. However, we have coaches in the field of strength and conditioning who tease other coaches for going through various certification classes and adding the multiple alphabets at the end of their last name.

Coaches need to understand that adding the various alphabets to the end of your last name after completing a certification course does not make you a better coach. Applying what you have learned from courses such as the Functional Movement Screen, Certified Functional Strength Coach, Performance Specialist, Certified Speed and Agility and the United States Weightlifting is what ultimately makes you a better coach. I have noticed that you find more coaches in the private sector who have attended several certification courses compared to a coach at the high school, collegiate, or professional level, because most coaches working in these various environments do not have the time to attend these clinics or study at home because of their work schedules.

Coaches need to understand that adding the various alphabets to the end of your last name after completing a certification course does not make you a better coach. Applying what you have learned does, says @DrRaymondTucker. Share on XQuestion C: “Should I be prepared to invest in my education as a coach?”

The answer to this question is also yes. As a strength and conditioning coach, you should take the time to educate yourself and improve. If taking a certification course from one of the leading experts in strength and conditioning will enhance your coaching ability, then you should take the course. Some of these certifications are being taught by experts in strength and conditioning who have traveled the world to learn from other strength and conditioning coaches, and they want to share what they have learned. So, why not pay to learn?

What makes me qualified to write this article is that as a young coach in the field, I tried to take every course I could because I was trying to learn from some of the best in the profession, and I just wanted to get better. Here are some of the courses I took:

- Functional Strength Coach Level 1

- Speed Specialist United States Track & Field Cross Country Association Certification

- Speed and Agility Coach

- Performance Specialist XPS

- Certified Functional Movement Screen

- Level 1 Sport Performance Certification

- Certified Strength and Conditioning Specialist (CSCS)

- Level 1 Track and Field Coach

And, yes, I added the various alphabets to the end of my last name, and I was never embarrassed to add them because I invested in my education as a coach. One of the early mistakes I made when taking these certification courses, however, is that I didn’t stop to apply what I learned in my training with my athletes or take the time to practice what I learned.

One of the early mistakes I made when taking certification courses, however, is that I didn’t stop to apply what I learned in my training with my athletes or take the time to practice what I learned, says @DrRaymondTucker. Share on XOver the years, I have now found myself going back through these courses and applying what I have learned with the athletes I work with. For example, one of the certification courses that I have gone back through a number of times is Michael Boyle’s Functional Strength, rereading the books and watching the videos over again. The certification is very practical and provides a simple process of getting good at the basics. I have used this training system with middle school, high school, and collegiate athletes as well as general population clients, and I have seen the improved results in movement, strength, power, and speed. Not only do the athletes enjoy the training, I also use this system in my own training and I have enjoyed the benefits of what I learned in this course.

My recommendation to any coach is to invest in your education by reading books, attending conferences, and taking certification courses. However, it’s essential to take the time to practice and apply what you have learned. If you complete and pass a certification course, be proud of your accomplishment and consider adding the letters indicating your certification to your last name: you’ve worked hard and invested your time in these courses, so celebrate your achievements. Don’t worry about other coaches who make dismissive comments about you for having several letters after your name. Throughout my coaching career, I’ve attended many conferences, and you would be surprised at the number of coaches who have multiple certifications and proudly display their “alphabet soup” after their names. You are responsible for your own learning as a coach, and do not let another coach discourage you from being your best—because, your athletes deserve your best.