What is speed? Why is speed important? And how do we develop speed?

Each of these questions serve as titles to the three ‘books’ that make up the ALTIS Need for Speed Course.

The excerpt below—taken from the middle of Book III: How Do We Develop Speed?—is directly preceded by a thought experiment.

Suppose you are the newly appointed S&C coach for a collegiate group of American football players and the Head Coach has tasked you with improving the speed of the team. After reviewing some film and speaking with various staff members and key athletes, you determine your focus will be on sprint mechanics and maximal sprint speed.

You have 3 sessions per week for 6 weeks prior to football activities—what do you do? How do you organize your training sessions?

How Do We Develop Speed (Excerpt)

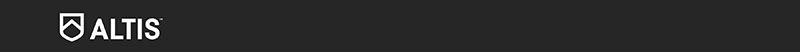

When it comes to facilitating the process of skill acquisition in sports, there are two primary approaches: from a systems-perspective, one can be thought of as ‘system-oriented,’ and the other is ‘parts-oriented’ (Figure 1, below).

The extreme end of the system-oriented approach is analogous to throwing your young child in at the deep end of a pool filled with a bunch of piranhas, and expecting her to swim. All learning at this end of the pool comes from performing the skill in full context all the time. At the other end of the pool, (and on the other side of a barrier, so no fish can get past) is the parts-approach, where learning is assumed to develop from first separating each part from the whole, and then plugging them back in once they have been mastered in isolation.

- “He scores great goals in practice, but always seems to panic when presented with goal-scoring opportunities in the game”

- “She plays great against the lesser teams, but always seems to fall apart against stronger teams”

- “He’s the fastest player, but never seems to run fast with pads and carrying the ball”

While we can all point to numerous examples like the above, we may have different rationale as to why they may occur. Often, the player’s ‘mentality’ is blamed—i.e., they are ‘mentally weak.’ But more often, it is probably that the player has not stabilized their patterns of movement in complex environments; the increased information leads them to perform in less than optimal ways.

Simply—there are too many piranhas in the pool.

Consider Jamaican sprinter Asafa Powell. Asafa has run the most sub-10 second 100m runs of all time (97 at the time of writing). He has been seemingly poised to win multiple global titles, but—despite often dominating smaller competitions—he was never able to appropriately manage the increased ‘information‘ that comes with international competitions, and instead has no individual Olympic medals, and only two from the World Championships.

In the relatively controlled world of track & field, this information really only manifests itself in greater levels of arousal from higher standards of competitors, bigger stadiums and crowds, more pressurized competition, etc. (additionally—especially in the jumping events—different weather conditions can be challenging, particularly for athletes who train predominantly indoors).

In team sport, on the other hand, this information is literally everywhere. It includes not only the increased arousal level from playing the actual game, but also team tactics, individual tactics and responsibilities, and the continuous, complex interactions with teammates and opponents.

So what can coaches do to increase the likelihood that athletes can manage the increasing magnitude and significance of information that occurs in the game?

We probably don’t just throw them in the deep end, and ask them to “figure it out,” right? And we probably don’t only perform repeated drills, under the assumption they will magically improve game-play, either.

Obviously, the truth exists somewhere in the middle: the appropriate removal of some amount of complexity from the skill in context so that the athlete is not overwhelmed by the sheer amount of information—but not too much such that it no longer represents the game in any significant way.

There are two general approaches to deciding how to remove complexity to aid in the learning objective:

- Decomposition

- Simplification

Before moving forward into this next section, please note that we are discussing motor learning, specifically. While related—and even somewhat intertwined—the organization of primary motor abilities (speed, strength, endurance, etc.) does not necessarily adhere to this distinction.

Decomposition

Simply put, task decomposition involves breaking a movement down into its component parts, training each part separately, and then reintroducing it into the whole movement under the assumption that it will improve the primary task.

This approach to learning is often called the ‘part-whole’ method, and generally includes the removal of, or reduction in, the amount of perceptual information—in many cases completely ‘decoupling’ perception from action.

Popular examples in sport include hitting a baseball off a tee, catching a football from a passing machine, and performing sprint drills.

Intuitively, this method makes a lot of sense and, in practice, coaches and athletes are often inspired by the process, and encouraged by the outcome: training the parts in isolation can lead to significant improvements in the execution of the part that is trained. A football player might, for example, break the sprinting skill down into its parts, and spend 10 minutes performing wall drills. Because of the relative simplicity of the task, it can be ‘perfected’ very quickly. This process of improvement encourages the player, and confirms the biases of the coach—as he observes the improvement in real time.

The player feels good about himself—confident in the task, and—even though there might be multiple generations between the part and the whole—he can see and feel the ‘connection’ to the extent that he can convince himself of the direct equivalence to the game task.

An outside observer might be impressed by this process: it is structured, it is ‘clean’, and he can observe clear improvement. The observer might consider this to be ‘good coaching.’

But he’d be wrong.

The problem is that learning should not look, or feel ‘clean’—it is messy. It requires that coaches place athletes in uncomfortable situations that present opportunities to make mistakes.

But how messy should it be? And how many errors are acceptable?

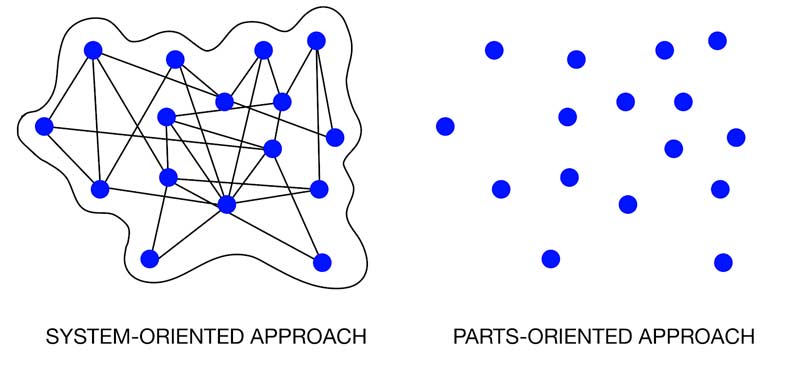

These are questions that the Challenge Point Hypothesis (CPH) attempts to answer.

Proposed by Guadagnolli and Lee in 2004 the goal of the CPH is to provide a framework for understanding how practice design variables influence skill acquisition.

Learning depends upon the functional difficulty of the task—and the CPH identifies three key points related to this:

- Learning does not occur in the absence of information: meaning, if an athlete is always successful, then the feedback is always the same—if there is no information, then there is no learning

- There is a Goldilocks Effect to the relationship between learning and information: too little, or too much, and learning is retarded

- For learning to occur, there is an optimal amount of information: This amount differs as a function of the skill level of each individual, and the difficulty of the to-be-learned task

Some might argue that the best athletes in the world have the ‘best technique,’ and for the most part, this is in fact true. Rarely will an athlete rise to the top of her sport without excellent fundamental technical abilities.

However, this is not the limiting factor to ultimate expertise.

As an athlete progresses through her development, expertise has increasingly less to do with how she can execute an isolated part of the game (the technique), and more to do with how she manages the information in the game (the skill).

Technique is important—but skill is more so!

The best athletes are not only the ones with the best technique; they are the ones with the best skill.

Technique is the content of an athlete’s movement; while skill is the technique in context—i.e., in the game. @ALTIS #NeedForSpeed. Share on XDecomposition focuses on the content.

Some coaches might feel that this part-whole method stabilizes techniques in less complex ways, so that they can be reintroduced at higher levels of complexity.

In reality, however, most coaches probably operate this way because it is easier, and looks better. It is far easier to choose from a list of drills than it is to design more representative training sessions, with the objective of greater transfer—and most of us are pretty uncomfortable with messy practices.

Skill is a problem-solving process, the solutions to which only make sense when considered in the context of information in the game. Therefore, if we want to improve an athlete’s skill, we need to provide them with problems they will encounter in the game.

The question is how do we do this?

With developing athletes—or with athletes who are experiencing specific problem-solving challenges, a preferred method to decomposition is simplification.

Simplification

“Without our context, we are not what we are. We are not a list of attributes. My aim is not to fracture and break apart what should be together, not to decontextualize. And that’s the oldest approach on earth.”—Manchester City Assistant Coach, Juanma Lillo.

In task simplification, movement and the information remain coupled—we simply scale the problems to the level appropriate to each athlete.

There are at least three primary ways 3 to do this:

- Reducing object difficulty: for example, youth football players playing with a smaller ball, youth basketball players shooting at a lower basket, or tennis players playing with a larger racket head and shorter handle

- Reducing attention demands: for example, manipulating the size of the field and the number of the players

- Reducing speed: simply governing the speed of the game or players within the practice.

Our friend, Dr. Rob Gray, identifies two keys to effective scaling:

- The coupling between the movement and the information should be similar to that which is required by the full skill

- An appropriate level of variability within the movement problems, so that athletes develop greater problem-solving abilities

Our challenge lies in how to do this effectively.

The process begins with investigating the athlete’s current movement behaviors in context to determine how movement solutions emerge within the game, so that we can appropriately identify where any weaknesses exist within their movement behavior repertoire.

If an athlete is having difficulty changing directions in the game, we might design the practice in such a way as to increase the number of change of direction problems the athlete will encounter (for example, by increasing the density of the playing area—creating a smaller area and more players). Similarly, if the athlete’s upright sprinting mechanics require improvement, rather than totally eliminating the relevant information and sprinting in isolation, we could design the practice such that there will be more opportunities to ‘open up and sprint’ (for example, by decreasing the density of the playing area— thus increasing the size of the practice area, and the number of players within it).

Such an approach to learning has been termed representative learning design which implies that the session goals revolve around precisely enhancing how a movement action occurs in its emergent process in sport.

“I think that the first thing that needs to be observed is something you cannot quantify easily. It’s the real game movements. If you’re a football player and you don’t add the football specifics into the model, it’s not a good model.”— J.B. Morin, ALTIS Interview, August, 2020

This is the opposite of a traditional approach to analyzing movement (i.e., a ‘movement screen’), which looks at the content of the movement first and foremost, and makes assumptions as to how it is executed in context.

We maintain that the initial level of analysis should be at the athlete-information interface: i.e., how the athlete moves in the game, and support this through studying and measuring the relevant underpinning capacities and abilities.

We then use this information to guide our training prescription to create more representative problems, and to better organize our training over the longer term to improve the skill in context.

Since you’re here…

…we have a small favor to ask. More people are reading SimpliFaster than ever, and each week we bring you compelling content from coaches, sport scientists, and physiotherapists who are devoted to building better athletes. Please take a moment to share the articles on social media, engage the authors with questions and comments below, and link to articles when appropriate if you have a blog or participate on forums of related topics. — SF

1 comment

Paul Harrison

Hi, very interesting as ever. The numbered links in the text do not have an associated bibliography at the end.