In 2011, I started my first internship at Longwood University under John Hark and Rick Canter. I was a Business Administration major with an interest in lifting weights and the desire to coach, but I didn’t know what exactly. A friend I trained with was interning for Coach Hark and suggested I reach out to him as well.

I understood only the basics of training (I went to the gym and worked out) and knew nothing about sports performance. The terms “kinesiology,” “biomechanics,” “triphasic,” “tier system,” and “energy system development” meant nothing to me, and to say I felt inadequate would be an understatement. I had no idea what I was doing, but within the first week I knew it was exactly what I wanted to do.

I’ve experienced three drastically different internships in my career, all at the college level. Overall, my time at Longwood was my best experience even though it was the “smallest” school. Why? It was the perfect blend of science and practice in a supportive environment. I was able to learn about the field and the science behind training, and most importantly, I coached every day for three years.

As I stepped into a full-time role, I wanted to develop an internship program that gave interns the best experience possible—a program that blended scientific truths, offered practical experience, and prepared interns to pursue any and every sector in the strength and conditioning field.

When developing an internship program from scratch, there were a few things I considered.

1. Start with Why

Determining the why behind a program will help guide us in the future when it comes to the growth or evolution of the program. The heart of any good program is rooted in education and service. We want to educate interns on the foundational principles of training, give them the practical experience to land a full-time job, and have a servant’s heart to guide them through this field. We tell our interns this in our first meeting and even during the interview process because it’s important for them to know what guides our decisions during this program.

We want to educate interns on the foundational principles of training, give them the practical experience to land a full-time job, and have a servant’s heart to guide them through this field. Share on XIf we’re starting an internship program to contribute to the future of the field, we’ll introduce and keep great people. If we’re starting an internship program to have bodies to clean and organize the weight room, then we shouldn’t have one in the first place.

I’m not saying interns shouldn’t do these things, because it’s part of the day-to-day responsibilities of any coach. I clean and organize the weight room every day. However, it can’t be the only thing a person experiences during their time with us. These types of internships push good people away from the field and leave them questioning what they saw in coaching in the first place.

2. Create a Deliberate Interview Process

Interview processes create the results they’re designed to produce. If we’re frustrated with the final product, then we need to change the interview process. This process should filter out any applicant that doesn’t fit our ideal candidate or culture. I’m not saying turn everyone away, but we need to be deliberate. Questions and discussion should require critical thinking, allow applicants to show their personality, and be transparent about what this position and career entails.

While marketing the internship, be upfront about the expectations and day-to-day experience interns will have. This includes the number of hours required, what the daily work looks like, and how they’ll be contributing to the department and training. This will help limit the number of applications and find the people we’re looking for.

To be honest, I’ve never turned away a person for an internship. However, we have open and honest dialogue during the interview. We describe what the field is like, what our jobs are day-to-day, and the long-term effort needed to be successful. This has led to applicants either realizing they want to go elsewhere or deciding this is exactly where they want to be. If a person is hesitant to get into this field based on this conversation, then this field probably isn’t for them.

3. Prepare Interns for the Next Step

Our goal at the end of our program is for interns to be able to coach from day one of their next stop. This doesn’t matter if it’s high school, college, private, or tactical: we want our interns to be confident in their ability to lead a room and program effectively.

Our goal at the end of our internship program is for interns to be able to coach from day one of their next stop, says @coachrgarner. Share on XAs a side note, I believe the most important skill of being a coach is public speaking. If we can’t speak confidently in front of large groups, then we’re going to struggle to lead a room. A coach may lack knowledge but still land a job because they can speak to and direct a crowd of people.

To fill our internship positions, we focus on recruiting freshman or sophomore students to our program. Why? This gives them an early start on their career to see if this field is something they’re interested in. Conversely, some may step in and realize it isn’t for them. That’s progress: now they know and can pursue other sectors instead of finding out they hate their “dream job” the last semester before graduation.

For those who decide this field is for them, we can pour into these students and guide them in the right direction. If they show potential, we can mold them into “assistant coaches,” and they’ll become another coach on the floor for the next 3–4 years.

By getting students in year one or two versus their last semester of college, we give them a massive advantage in the job market. If they intern from their sophomore year on, they could have three different internships under three different staffs by the time they graduate. With that much experience and networking, they’ll be able to land a GA or full-time position upon graduating. At the very least, they’ll land an excellent internship under a high-level coach. (I’d advise pursuing a big-time internship the summer before their senior year.)

4. Develop a Curriculum

Educating interns should be a significant portion of our program. As coaches in the field, it is our job to lead and educate the next generation. Developing a curriculum ensures we are teaching the foundational topics and skills needed to be successful without going off-track or missing topics.

If we don’t have a written-out curriculum, then it can be hard to stay on task or have a progression of topics. There are times when we want to sit down and answer any questions interns have, which can lead to great discussions, but we still need to have a curriculum in place.

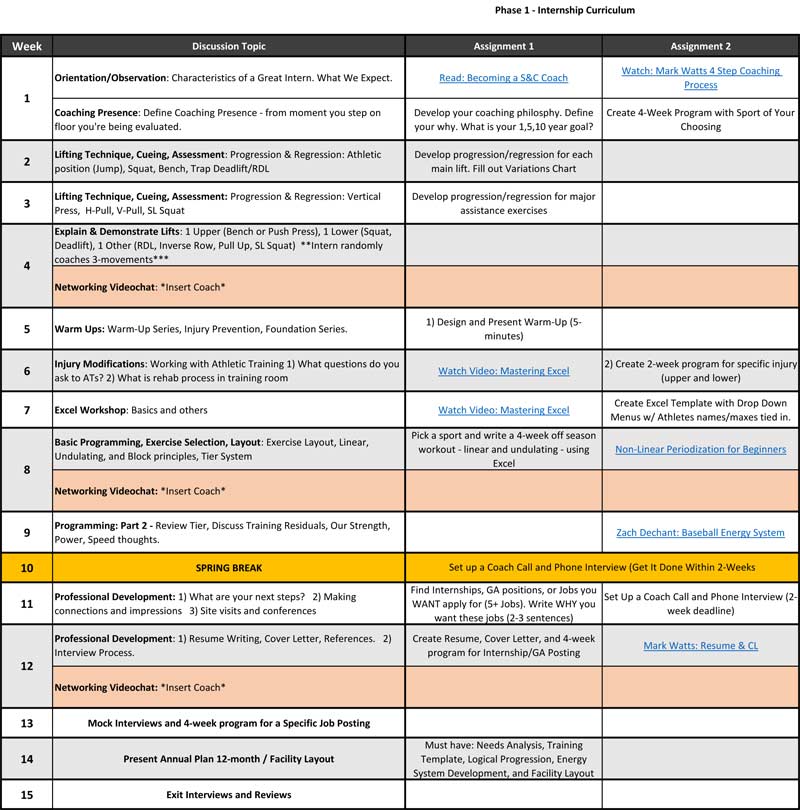

Table 1 shows a sample of the curriculum we’ve previously used. We focus on the practical side because most students lack this experience. Since they’re getting the detailed science in class, we want to fill in the back-end with practical information to help present the whole picture. Do we discuss scientific topics? Absolutely, but the practical side is what separates average from great coaches. Topics covered include lifting technique, assessment, warm-up, injury modification, Excel, programming, and professional development.

The two biggest takeaways for our interns were always the Excel workshop and video calls with coaches. It’s vital to show interns how to use Excel, as most have never used it, and Excel is a strength coach’s best friend. This is a unique skill set for coaches. It also helps applicants stand out and may land them a job, as not every place will have resources yet to manage and distribute their workouts.

5. Let Interns Coach

The purpose of internships is to connect the classroom to the real world and letting interns coach is as real world as it gets. If we only instruct our interns to clean, then we’re wasting their time. What’s the best way to serve and educate interns? Letting them coach under our supervision.

In my first internship, I was able to coach and lead different parts of workouts regularly. Although I lacked the scientific knowledge compared to my peers, I could lead and coach a room better than most, setting me apart. Starting out, I preferred learning how to coach from the floor versus from a place of deep scientific knowledge, believing I could learn biomechanics, energy system development, and programming on my own. However, learning the soft skills of communication, emotional awareness, critical thinking, and time management takes time and often requires positive and negative experiences to form. In the end, soft skills typically make or break a hire, which is why internship programs should focus these skills.

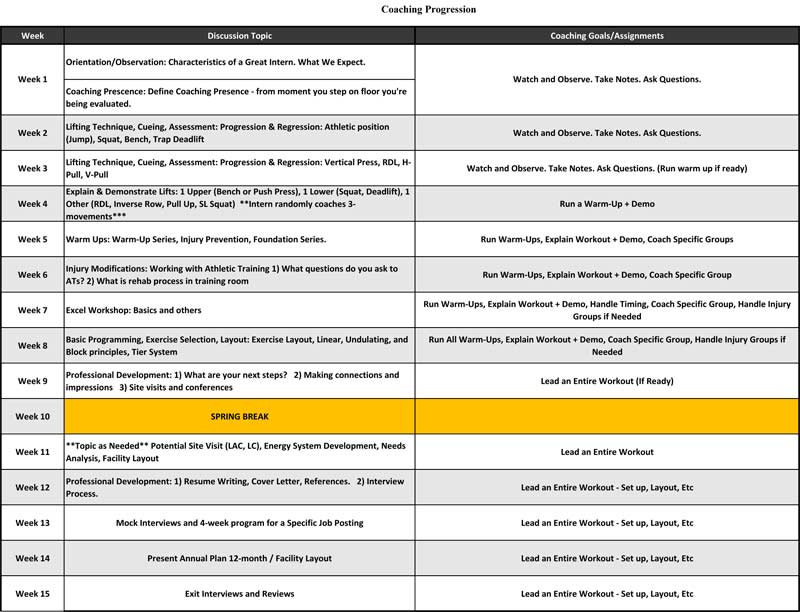

Soft skills—communication, emotional awareness, critical thinking, time management—typically make or break a hire, which is why internship programs should focus these skills, says @coachrgarner. Share on XTo get interns started, I have found it useful to organize a coaching progression (shown in table 2) and have them lead the warm-up, explain the workout, handle time intervals, lead post-stretch, or coach a rack. Start small and work up.

Some interns can step in on the first day and lead, while others may take more time. Overall, what matters is that we’re letting our interns coach more with time. I’ve had internships where I led teams for a whole year, and others where I wasn’t allowed to coach until the last day of the internship. I know exactly which one had the greater impact on my development as a coach.

6. Integrate Technology into the Experience

The use of laser timers, jump mats, heart rate monitors, and other technology is prevalent in our field today. If the department owns and uses technology, take the time to teach interns how to use it, how to collect and organize data, and how to interpret the data to make training decisions.

For the future of our profession, it’s crucial we teach interns how to use this technology and also to not be controlled by it. Technology is a tremendous tool, but at the end of the day, coaches must make the training decisions. Screens can’t replace the coaching eye.

There may be a time where a department has no technology available. Considering this, it’s important to educate interns on ways to train and evaluate programs without technological assistance. They might be hired somewhere without a budget, and it’s important we don’t set them up to be unable to show the administration that they can do their job effectively.

7. Teach Interns How to Train

We hear this all the time, but it’s the truth. An intern doesn’t have to be the strongest person in the room, but they need to know how to train. We learn by doing, and this is especially true when it comes to lifting. Getting under the bar is the best teacher we have. The only way we’ll know what a heavy squat feels like is to get under the bar and do it. The same can be said for speed and jump development. As a coach, if we’re going to prescribe something, we need to know what it feels like and what the recovery process looks like after the fact.

As a coach, if we’re going to prescribe something, we need to know what it feels like and what the recovery process looks like after the fact, says @coachrgarner. Share on XIf schedules align, we have interns train with the S&C staff. This is often when we get to know each other and build a stronger relationship. Personally, I have interns follow the program I’m doing unless they have a dedicated training plan or goal, such as Olympic weightlifting. My caveat is if I see they aren’t training consistently and diligently, then they’ll start training with the staff.

The other option is to follow the training plan the athletes are doing. I’ve seen this be a tremendous bonding tool for the interns and athletes. If the team knows the intern is following the program, they’ll ask them about the workout, how it felt, and the difficulty. On the flip side, the interns know how the athletes will feel during training and can coach them through it.

An underrated experience that we also need to teach is what constitutes hard training. To me, this means training when we don’t want to, pushing ourselves beyond our limits, and experiencing productive discomfort. This doesn’t mean reckless, excessive, and dangerous training, but there is a place for experiencing tough training cycles with amplified intensity and volume.

Build a Program for the Future

A well-rounded internship program can be a tremendous asset to any school or department. It provides a place for interns to learn and gives coaches a network of potential assistant coaches to hire in the future. Although we may be hesitant to let interns coach or lead specific parts of training, it’s critical to their development.

Although we may be hesitant to let interns coach or lead specific parts of training, it’s critical to their development, says @coachrgarner. Share on XInterns don’t need to write programs or take over entire teams. We can easily let them explain workouts, lead warm-ups, or coach athletes walking around the room. The practical experience is what internships exist to provide. Our internship programs should provide opportunities for interns to learn and experience what coaching is like with the support of a professional to help them progress. Remember, interns will determine the future of our profession, and their experiences will positively or negatively impact the next generation.

Since you’re here…

…we have a small favor to ask. More people are reading SimpliFaster than ever, and each week we bring you compelling content from coaches, sport scientists, and physiotherapists who are devoted to building better athletes. Please take a moment to share the articles on social media, engage the authors with questions and comments below, and link to articles when appropriate if you have a blog or participate on forums of related topics. — SF