From 1994 to 2006, anterior cruciate ligament (ACL) reconstructions increased by an astronomical 924% in individuals under the age of 15.1 Through a physical activity promotion lens, this number may indicate that young people continue to engage in sports, especially at competitive levels, even with some noted declines in overall youth physical activity participation. Interestingly, this data comes from a period when sport specialization and year-round sport models (>8 months/year) were not dominant; that is, youth were not exclusively playing a single sport during elementary years. The increased exposure to sports participation has clear physical, social, and psychological benefits,2 but the medical burden and consequences of ACL injuries and reconstructions make it feel like the house is on fire.

Sports participation has clear physical, social, and psychological benefits, but the medical burden and consequences of ACL injuries and reconstructions can make it feel like the house is on fire. Share on XIn 2005, some seminal work with injury-related fear and ACL reconstruction began to emerge when physical function, return to pre-injury levels of activity/competition, and other clinical outcomes could not be explained by traditional laboratory measures like biomechanics, strength, etc.3,4 Injury-related fear quickly became supported as a determinant of knee function, secondary ACL injury risk, and overall physical activity levels after ACL reconstruction. The difficulty in addressing injury-related fear—a complex and very individual response—can develop from a few areas:

- Increased rates of ACL injury.

- Who is at the center of the care team.

- Bridging the gap for athletes to return to an unpredictable and dynamic environment.

Nassim Taleb, an economist and author, developed the black swan theory. Black swan events are improbable, have far-reaching consequences, and are both difficult to predict (they take everyone by surprise) but obvious in hindsight. Despite the staggering percentages given a few sentences earlier, if we sit down and calculate the hours of exposure for each ACL injury, we may begin to see ACL injuries as an extreme outlier (even if they’re a common orthopedic injury) that have drastically changed the landscape of sports medicine as we know it. Some have found the incidence of non-contact ACL tears less than 0.1 per 1,000 player-hours between males and females, which included over 5 million player-hours and 40 million player exposures.5 Another study has shown ACL injury rates at 6.5 per 100,000 athletic exposures from 2007 to 2012.6

However, as the stakes increase (athlete safety and longevity, injury reduction, medical burden, etc.), it feels like the notion of ACL injuries being “improbable” is misplaced. There’s no question that ACL injury is devastating on both physical and psychological outcomes and that there’s a growing rate of ACL injuries, with some expecting overall rates to double by 2030.7

In an effort to slow these rates down, researchers have focused on biomechanics, strength, and other physical measures or mechanisms. Researchers are often (fairly) critiqued for living in ivory towers and not engaging community stakeholders (coaches, athletes, athletic administrators, etc.), which may be stoking the fire a bit from inside the house.

Qualitative work has begun to be incorporated into sports medicine research, which creates an avenue for the inclusion of stakeholder perspectives—what are the barriers and facilitators you face as a (fill in the blank with your role in sports) when it comes to ACL injury reduction?8,9 Sports medicine research has shifted from a disease-focused approach to a biopsychosocial approach or an emphasis on psychologically informed clinical care and athlete-centered care. Sometimes, care and performance enhancement can be as simple as asking someone what they want/need and supporting that through your skills and expertise.

The central drive to decrease ACL injury rates shouldn’t attempt to predict ACL injuries but rather build a robustness to negative physical and psychological stressors and exploit positive stressors. Share on XHot take: The central drive to decrease ACL injury rates should not attempt to predict ACL injuries but rather build a robustness to negative stressors, including:

- Physical (overtraining, undertraining)

- Psychological (lack of social support, school workloads, lack of sleep)

This should be done while, at the same time, exploiting positive stressors: we need to adjust to the existence of ACL injuries rather than try to predict them.

Adopting an Athlete-Centered, Multidisciplinary Approach

Sports medicine teams are uniquely suited to collaborate to improve athlete experiences AND reduce injury risk in active populations or build robustness in athletes. This should be a multidisciplinary approach between strength and conditioning staff, athletic trainers, physical therapists, and counseling and psychological staff—but the athlete must remain the center of this effort.

Evidence-based practice leverages provider experience and research evidence, but this model falls short without individual preferences and beliefs. As such, no single focus is likely to produce a great outcome—a focus solely on research evidence will fail if the care team doesn’t have the skills (or resources) to implement these methods. For a while, research on ACL injury homed in on strength and biomechanical deficits, which meant we missed out on these athletes’ psychosocial experiences, which we know now are a critical factor in this complex web.9–11

Athletes are exceptional in their ability to compensate and adapt to the challenges they face. We expect our athletes to return to sport or activity despite these challenges, and they usually do. However, if we don’t consider the multifactorial consequences of ACL injury, we aren’t fully preparing our athletes to return to unpredictable environments. There is a critical gap to bridge between post-injury recovery and return to play after ACL injury.

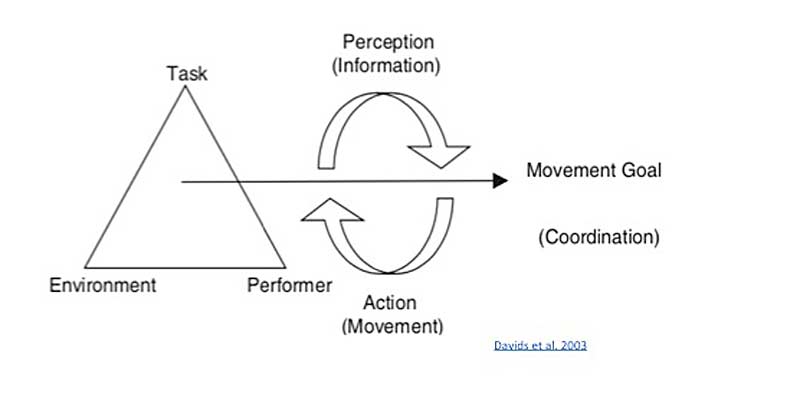

The Integrated Model of Response to Sport Injury, introduced by Wiese-Bjornstal12, provides a great visual to understand how pre-injury factors influence a stress (physical and mental) response leading to sport injury.

(Figure adapted from Davids et al, 2003.)

The focus here is the cycle of recovery outcomes, which is influenced by:

- Personal factors (injury severity, self-perceptions, coping skills).

- Situational factors (time in season, teammates and coaches, social support, access to equipment).

- Emotional responses (positive emotional responses, fear).

- Behavioral responses (adherence to rehab and sessions, effort and intensity, risk-taking behaviors).

Injury-related fear is an umbrella encompassing kinesiophobia (fear of movement), fear of reinjury, and other fear-avoidance beliefs.13,14 There are several patient-reported outcome measures to assess these responses, like the Tampa Scale of Kinesiophobia and the Athlete Fear Avoidance Beliefs Questionnaire.

If you work with an athlete consistently and have built an inclusive rapport, they may share feelings of anxiety, fear, or distrust in their body. Rehabilitation and return to sport take a massive physical, emotional, and psychological toll on our athletes. Most of them will have a strong athletic identity that is challenged when they miss a substantial amount of time in their sport, and some will have minimal coping skills, which lends to an inability to address stressors or a poor cognitive appraisal of situations.

As much you emphasize strength, speed & power during the season, include psychological coping skills. Hold athletes accountable but give them the space, time & resources to process their emotions. Share on XAs much as strength, speed, and power are emphasized during the season, psychological coping skills should be included. There is still a strong and prevalent stigma15 in athletics where athletes who show emotion or struggle are called out in front of their peers, shamed for their frustrations, called weak, and worse. Athletes can be held accountable but also given the space, time, and resources to process their emotions.

If you’re in a position working with young athletes, it is crucial to note that many of these individuals may also not have the emotional vocabulary to share exactly how they are feeling or have experience with regulating those emotions. The emotional-processing areas in the brain don’t fully develop until age 25, so “young” is relative and likely applies to athletes in most settings.

Fear and Return to Sport

Injury-related fear usually seems to manifest when athletes begin the transition in rehabilitation to functional activities (single-leg hops, decelerating, cutting, etc.) and return to sport. Some studies have shown that early measures (0–2 months after ACL reconstruction) of self-reported fear predict later levels of fear during these functional transitions.16

On the physical performance side, athletes need to be prepared for interacting with a chaotic environment and autonomously executing a massive number of movements in a variety of conditions.17 Motor learning should be a cornerstone of this effort—as important as programming and load management are, you should ground these approaches in motor learning theories. These theories can also help identify athletes who are struggling to improve their physical performance and/or experiencing a poor psychological response that is impairing their ability to perform.

Full disclosure: There’s not a single theory that encompasses everything, but my favorite is Newell’s Theory of Constraints (Dynamic Systems), which includes individual, task, and environment. In this constraint-led approach, there are emergent properties of the whole system (individual, task, environment) that can be used to understand the self-organization of the individual and intrapersonal relationships in the environment (increased high-risk contact, avoidance of contact, “lost in space”).

For individual constraints within Newell’s Theory, we can have sublevels for structural and functional changes. Structural changes after ACL reconstruction are well described for the knee: poor strength, inefficient force production, asymmetric functional movements, and plenty more. Researchers have also seen functional changes in brain activity and connectivity between brain regions after ACL reconstruction. These changes may indicate a shift in how ACL-reconstructed individuals use sensory information (visual information) and a predisposition to fear or anxiety (Grooms, 2017; Baez, 2021).18,19

Injury-related fear has been implicated in both structural and functional changes.20–23 Critically, if you suspect an athlete has feelings of fear or anxiety or hear them admit this, pushing through that exercise can be detrimental at the structural and functional levels. Athletes experiencing fear can adopt a more internal focus of attention, which will disrupt motor performance and break down coordination.24

Injury-related fear has been implicated in both structural and functional changes. It’s not as simple as telling an athlete to ‘get over it,’ as there are incredibly complex relationships at play. Share on XIt’s truly not as simple as telling an athlete to “get over it”—there are incredibly complex relationships at play. Take the time to validate their anxiety and refer them out if their fear and anxiety are sustaining over two weeks or interfering with their activity or quality of life. Referral should be made to a sport psychologist, a licensed doctoral-level provider, or other appropriate mental services provider. Be very wary of those who advertise themselves as a performance coach but hold no formal training, extensive mentorship, or educational background (AASP or CMPC).

Coaches and other members of the sports medicine team can help athletes regain confidence by appropriately exposing them to exercises/drills, affirming and celebrating them during this process, and keeping them engaged with their social support (usually the team).

1. Graded exercise25,26: Coaches, especially strength and conditioning coaches, are exceptional at programming and seeing the big picture performance peaks during seasons. On a smaller scale, load and exercise programming should be very intentional and individually graded. Some athletes may struggle with symmetrical squatting or running, so breaking down those complex exercises into smaller, easily accomplished exercises will help give your athlete the building blocks to be confident.

If you notice that progressing to exercises induces a regression in performance, this is partly expected—but give the athlete a chance to be “messy” before hounding corrections. Some athletes will naturally self-evaluate and know when a specific set wasn’t their best; acknowledge and affirm their feelings and give feedback if requested/required.

In the weeds: Focus of attention also plays a vital role in performance improvement and will benefit motor learning. An external focus of attention is directing attention toward things outside of the body, like the environment and goal of the movement. An internal focus of attention is concentrated on how their body moves in space. Most rehabilitation specialists and coaches use internal, which may be taxing mental resources.27–29

2. Practice and return to sport structures30–32: Differential learning capitalizes on purposefully creating a varied and random practice. With support from Newell’s Theory of Constraints, this method supports a self-organized process of learning movements and skills, which introduces a healthy variability of movements given the environmental context and constraints. Building on our graded exercises, changing task parameters could look like this—before performing a broad jump:

- Skip with your right leg, or

- Perform butt kicks, or

- Perform a shuffle to the right/left.

To change the environment, perform exercises in different light conditions, without shoes, with loud music, etc. To change athlete parameters, have them complete exercises while fatigued, with additional weight (when safe), etc. Often, this is far from the standard in most rehabilitation and return to sport settings, where athletes are given a strict 3×10 of a particular exercise in a highly controlled environment. There should be an emphasis on safe progressions, but variety can otherwise be introduced in plenty of ways.

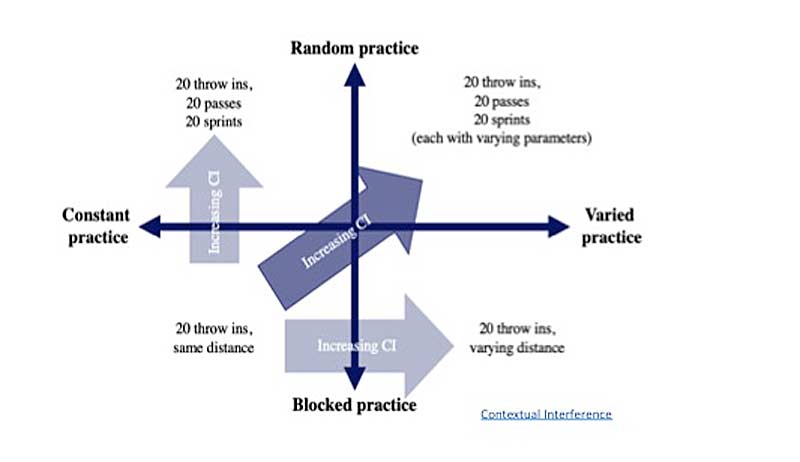

In the weeds: Contextual interference (CI) considers the variability of the tasks being performed and the scheduling of practices. CI can help speed up skill acquisition despite poor practice performance, which is intentionally targeted. High CI, or random practice order, yields better skill retention and transfer despite those poor performances. Low CI would mean one task is completed before moving to the next, which seems to be the standard across the board.33,34

(slide via Sports Science Insider.)

3. Incorporating psychological support into the coaching process: Coaches can emphasize positive coping skills like mindfulness meditation, journaling, reframing, or other relaxation techniques.35 It is also essential to normalize feeling bad or not normal sometimes—don’t tell them it could be worse or feel like you need to share your experience. Hear them, affirm them, and try to find the root, if possible.

Incorporating pre-season mental skills training seems to help reduce injury risk for your entire team and sets your athletes up with important coping strategies for when the season picks up. Share on XIncorporating pre-season mental skills training seems to help reduce injury risk for your entire team and sets your athletes up with important coping strategies for when the season picks up.36 If you’re working with an athlete returning from injury, mindfulness can be introduced at the beginning of each session to reduce potential anxiety and allow them the space to be ready to proceed. YouTube and other free resources are readily available if you aren’t sure where to start. Using the concepts above will also promote motor learning and enhance your athlete’s ability to relearn these skills after ACL injury.

Empowering Athletes and the Path to Recovery

Sports medicine teams are critical in helping athletes transition back to sport and improve their quality of life after ACL injury. These teams are often essential sources of support for athletes, no matter what stage of life they are in. Simple human-level things like building mindfulness into strength programming or imagery into rehabilitation support the physical and psychological well-being of athletes.

Whatever your specific role, you possess the expertise and capabilities to implement some form of psychologically informed and athlete-centered care. The escalating rates of ACL injury and reconstructions in sport demand a level of intentionality in engaging both physical and mental well-being, which will have far-reaching benefits beyond the athlete’s sport. Psychological skills should be trained and valued in the same manner that squats, sprints, and scores are.

Lead Image by Fred Kfoury III/Icon Sportswire.

Since you’re here…

…we have a small favor to ask. More people are reading SimpliFaster than ever, and each week we bring you compelling content from coaches, sport scientists, and physiotherapists who are devoted to building better athletes. Please take a moment to share the articles on social media, engage the authors with questions and comments below, and link to articles when appropriate if you have a blog or participate on forums of related topics. — SF

References

1. Buller LT, Best MJ, Baraga MG, and Kaplan LD. “Trends in Anterior Cruciate Ligament Reconstruction in the United States.” Orthopaedic Journal of Sports Medicine. 2014;3(1):2325967114563664. Published 2014 Dec 26. doi:10.1177/2325967114563664

2. Pluhar E, McCracken C, Griffith KL, Christino MA, Sugimoto D, and Meehan WP 3rd. “Team Sport Athletes May Be Less Likely to Suffer Anxiety or Depression than Individual Sport Athletes.” Journal of Sports Science and Medicine. 2019;18(3):490–496. Published 2019 Aug 1.

3. Kvist J, Ek A, Sporrstedt K, and Good L. “Fear of re-injury: a hindrance for returning to sports after anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction.” Knee Surgery, Sports Traumatology, Arthroscopy. 2005 Jul;13:393–397.

4. Chmielewski TL, Jones D, Day T, Tillman SM, Lentz TA, and George SZ. “The association of pain and fear of movement/reinjury with function during anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction rehabilitation.” Journal of Orthopaedic & Sports Physical Therapy. 2008 Dec;38(12):746–753.

5. Chia L, De Oliveira Silva D, Whalan M, et al. “Non-contact anterior cruciate ligament injury epidemiology in team-ball sports: a systematic review with meta-analysis by sex, age, sport, participation level, and exposure type.” Sports Medicine. 2022 Oct;52(10):2447–2467.

6. Joseph AM, Collins CL, Henke NM, Yard EE, Fields SK, and Comstock RD. “A multisport epidemiologic comparison of anterior cruciate ligament injuries in high school athletics.” Journal of Athletic Training. 2013 Dec 1;48(6):810–817.

7. Maniar N, Verhagen E, Bryant AL, and Opar DA. “Trends in Australian knee injury rates: An epidemiological analysis of 228,344 knee injuries over 20 years.” The Lancet Regional Health–Western Pacific. 2022 Apr 1;21.

8. Little C, Lavender AP, Starcevich C, et al. “Understanding Fear after an Anterior Cruciate Ligament Injury: A Qualitative Thematic Analysis Using the Common-Sense Model.” International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2023 Feb 7;20(4):2920.

9. Burland JP, Toonstra J, Werner JL, Mattacola CG, Howell DM, and Howard JS. “Decision to return to sport after anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction, part I: a qualitative investigation of psychosocial factors.” Journal of Athletic Training. 2018 May 1;53(5):452–463.

10. Erickson LN, Jacobs CA, Johnson DL, Ireland ML, and Noehren B. “Psychosocial factors 3‐months after anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction predict 6‐month subjective and objective knee outcomes.” Journal of Orthopaedic Research®. 2022 Jan;40(1):231–238.

11. Burland JP, Toonstra JL, and Howard JS. “Psychosocial barriers after anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction: a clinical review of factors influencing postoperative success.” Sports Health. 2019 Nov;11(6):528–534.

12. Wiese-Bjornstal DM, Smith AM, Shaffer SM, and Morrey MA. “An integrated model of response to sport injury: Psychological and sociological dynamics.” Journal of Applied Sport Psychology. 1998 Mar 1;10(1):46–69.

13. Meierbachtol A, Obermeier M, Yungtum W, et al. “Injury-related fears during the return-to-sport phase of ACL reconstruction rehabilitation.” Orthopaedic Journal of Sports Medicine. 2020 Mar 26;8(3):2325967120909385.

14. Hsu CJ, Meierbachtol A, George SZ, and Chmielewski TL. “Fear of reinjury in athletes: implications for rehabilitation.” Sports Health. 2017 Mar;9(2):162–167.

15. Chow GM, Bird MD, Gabana NT, Cooper BT, and Becker MA. “A program to reduce stigma toward mental illness and promote mental health literacy and help-seeking in National Collegiate Athletic Association Division I student-athletes.” Journal of Clinical Sport Psychology. 2020 Jul 28;15(3):185–205.

16. Bullock GS, Sell TC, Zarega R, et al. “Kinesiophobia, knee self-efficacy, and fear avoidance beliefs in people with ACL injury: a systematic review and meta-analysis.” Sports Medicine. 2022 Dec;52(12):3001–3019.

17. Khadartsev AA, Nesmeyanov AA, Es’ Kov VM, Fudin NA, and Kozhemov AA. “The foundations of athletes’ training based on chaos theory and self-organization.” Theory and Practice of Physical Culture. 2013(9):23.

18. Grooms DR, Page SJ, Nichols-Larsen DS, Chaudhari AM, White SE, and Onate JA. “Neuroplasticity associated with anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction.” Journal of Orthopaedic & Sports Physical Therapy. 2017 Mar;47(3):180–189.

19. Baez S, Andersen A, Andreatta R, Cormier M, Gribble PA, and Hoch JM. “Neuroplasticity in corticolimbic brain regions in patients after anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction.” Journal of Athletic Training. 2021 Apr 1;56(4):418–426.

20. Genoese F, Baez SE, Heebner N, Hoch MC, and Hoch JM. “The relationship between injury-related fear and visuomotor reaction time in individuals with a history of anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction.” Journal of Sport Rehabilitation. 2020 May 29;30(3):353–359.

21. An YW. “Fear of reinjury matters after ACL injury.” International Journal of Applied Sports Sciences. 2018 Dec 1;30(2).

22. Paterno MV, Flynn K, Thomas S, and Schmitt LC. “Self-reported fear predicts functional performance and second ACL injury after ACL reconstruction and return to sport: a pilot study.” Sports Health. 2018 May;10(3):228–233.

23. Trigsted SM, Cook DB, Pickett KA, Cadmus-Bertram L, Dunn WR, and Bell DR. “Greater fear of reinjury is related to stiffened jump-landing biomechanics and muscle activation in women after ACL reconstruction.” Knee Surgery, Sports Traumatology, Arthroscopy. 2018 Dec;26:3682–3689.

24. Young WR and Williams AM. “How fear of falling can increase fall-risk in older adults: applying psychological theory to practical observations.” Gait & Posture. 2015 Jan 1;41(1):7–12.

25. Vlaeyen JW, de Jong J, Sieben J, and Crombez G. “Graded exposure in vivo for pain-related fear.” Psychological Approaches to Pain Management. A Practitioner’s Handbook. New York: Guilford. 2002:210–233.

26. Baez S, Cormier M, Andreatta R, Gribble P, and Hoch JM. “Implementation of In vivo exposure therapy to decrease injury-related fear in females with a history of ACL-Reconstruction: A pilot study.” Physical Therapy in Sport. 2021 Nov 1;52:217–223.

27. Singh H, Gokeler A, and Benjaminse A. “Effective attentional focus strategies after anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction: a commentary.” International Journal of Sports Physical Therapy. 2021;16(6):1575.

28. van Weert MB, Rathleff MS, Eppinga P, Mølgaard CM, and Welling W. “Using a target as external focus of attention results in a better jump-landing technique in patients after anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction–A cross-over study.” The Knee. 2023 Jun 1;42:390–399.

29. Gokeler A, Benjaminse A, Welling W, Alferink M, Eppinga P, and Otten B. “The effects of attentional focus on jump performance and knee joint kinematics in patients after ACL reconstruction.” Physical Therapy in Sport. 2015 May 1;16(2):114–120.

30. Gokeler A, Neuhaus D, Benjaminse A, Grooms DR, and Baumeister J. “Principles of motor learning to support neuroplasticity after ACL injury: implications for optimizing performance and reducing risk of second ACL injury.” Sports Medicine. 2019 Jun 1;49:853–865.

31. Gokeler A, Nijmeijer EM, Heuvelmans P, Tak I, Ramponi C, and Benjaminse A. “Motor learning principles during rehabilitation after anterior cruciate ligament injury: Time to create an enriched environment to improve clinical outcome.” Arthroskopie. 2023 Apr 26:1–7.

32. Kakavas G, Forelli F, Malliaropoulos N, Hewett TE, and Tsaklis P. “Periodization in anterior cruciate ligament rehabilitation: new framework versus old model? A clinical commentary.” International Journal of Sports Physical Therapy. 2023;18(2):541.

33. Gokeler A, Seil R, Kerkhoffs G, and Verhagen E. “A novel approach to enhance ACL injury prevention programs.” Journal of Experimental Orthopaedics. 2018 Jun 18;5(1):22.

34. Benjaminse A, Neuhaus D, Gokeler A, Grooms D, and Baumeister J. “Principles of motor learning to support neuroplasticity after ACL injury.” Sports Medicine. 2019 June;49(6):853–865.

35. Birrer D and Morgan G. “Psychological skills training as a way to enhance an athlete’s performance in high‐intensity sports.” Scandinavian Journal of Medicine & Science in Sports. 2010 Oct;20:78–87.

36. Reiche E, Lam K, Genoese F, and Baez S. “Integrating Mindfulness to Reduce Injury Rates in Athletes: A Critically Appraised Topic.” International Journal of Athletic Therapy and Training. 2023 Aug 28;1(aop):1–8.