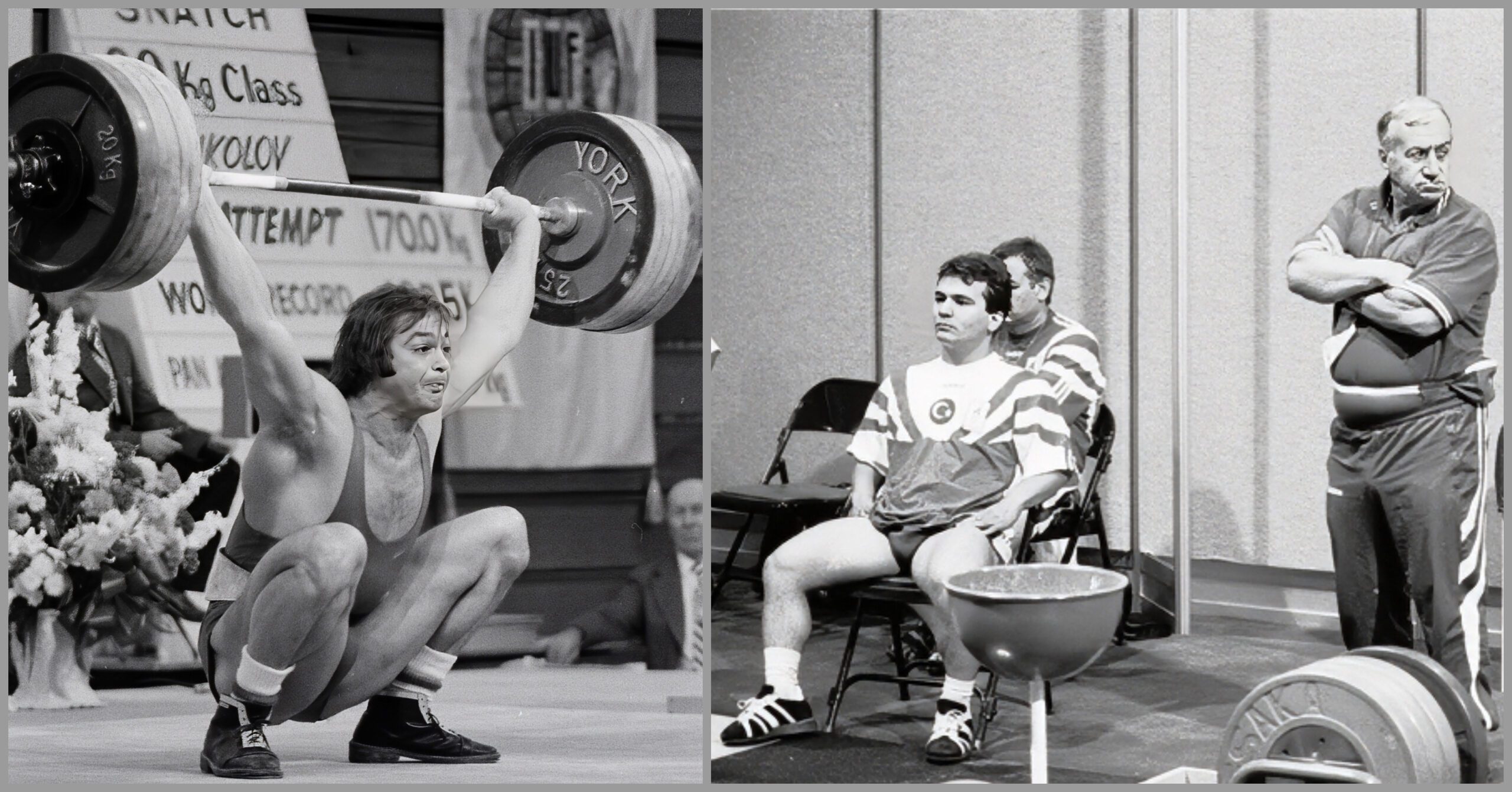

Although strength coaches rarely use wave loading, the method has a proven track record for developing the fastest, most powerful muscle fibers. I was first introduced to wave loading 50 years ago through an article about Bulgarian weightlifter Andon Nikolov in Muscle Builder/Power magazine—Nikolov won gold at the 1972 Olympics and later broke four world records. More about Nikolov later, but let’s start my sales pitch by reviewing how muscles function.

Motor units tell muscles to contract. There are low-threshold and high-threshold motor units, with the high-threshold motor units controlling the fastest, most powerful muscle fibers. The catch is that higher threshold motor units are recruited only when the central nervous system determines that greater muscle force is necessary.

Citing neurological development, Russian sprint coach Ben Tabachnik (PhD) says the best ages for increasing stride frequency are generally between 8 and 13. This restriction suggests that more mature sprinters typically experience greater performance improvements due to variables such as improved stride length. This idea is evident when comparing the difference in stride length between Usain Bolt’s 100m world records in 2008 and 2009.

In 2008, Bolt ran 9.69 to shatter the world record, and the following year he improved to 9.58. One difference was that Bolt covered the distance in 41.4 steps in 2008, compared to 40.92 steps in 2009. (For reference, in 1991, Carl Lewis set a world record of 9.86, finishing the race in 43 steps.) OK, so what does this have to do with pumping iron?

Stride length is strongly influenced by how much force the athlete applies to the ground (as I assume Bolt’s leg bones didn’t get longer between 2008 and 2009). In a study involving 33 sprinters published in the Journal of Applied Physiology, researchers concluded that “…runners reach faster top speeds not by repositioning their limbs more rapidly in the air, but by applying greater support forces to the ground.” This effect is illustrated in Image 1 below, where the power this athlete generated by hip, knee, and ankle extension elevated her above the ground, increasing the distance she covered with each step. This brings us to the concept of “mass-specific force.”

Barry Ross is the author of the track and field classic Underground Secrets to Faster Running and worked with Allyson Felix. Ross discussed the importance of mass-specific force in sprinting. “It isn’t merely the amount of force applied to the ground that increases stride length; it’s the amount of force in relation to bodyweight.” For this reason, Ross believed that increased strength developed by lifting weights could translate into faster sprinting times if those gains are not associated with a significant increase in bodyweight. Let me expand on this point.

Many sprint coaches don’t see the strength developed in the weightroom transfer to the track because they use (often unintentionally) bodybuilding protocols. Bodybuilding protocols encourage the development of substances that increase size and weight but do not (for lack of a better word) amplify muscle power. This “sarcoplasmic hypertrophy” is one reason bodybuilders, although strong, are often not as strong as they appear.

Many sprint coaches don’t see the strength developed in the weightroom transfer to the track because they use (often unintentionally) bodybuilding protocols that increase size and weight but do not ‘amplify’ muscle power. Share on XTo improve mass-specific force, sprinters must focus on developing just the muscle fibers, a process known as “myofibrillar hypertrophy.” Ross noted that when Felix improved her deadlift from 125 to 300 pounds, she only increased her bodyweight by two pounds. Ross believes this led to her improving her 200m sprint time from 22.83 to 22.11 (22.30 adjusted for altitude).

The takeaway is that if running faster or jumping higher is a priority, you must find ways to get stronger without getting bigger. Wave loading is a way to do just that.

The Switch to Fast Twitch

Wave loading is a variation of contrast training, scientifically referred to as “Post-Tetanic Potentiation” (PTP). PTP suggests that prior muscular contractions affect a muscle’s ability to generate subsequent force.

In the early 1980s, Bigger Faster Stronger (BFS) began showcasing a striking demonstration of contrast training during their athletic fitness clinics. BFS clinicians would have an athlete perform a vertical jump, which they would measure. The athlete would then work up to a heavy set of box squats and retest their vertical. Because the box squat recruits the fast-twitch muscles without excessively fatiguing the legs, those fibers remain activated and powerful during the retest, enabling them to jump higher.

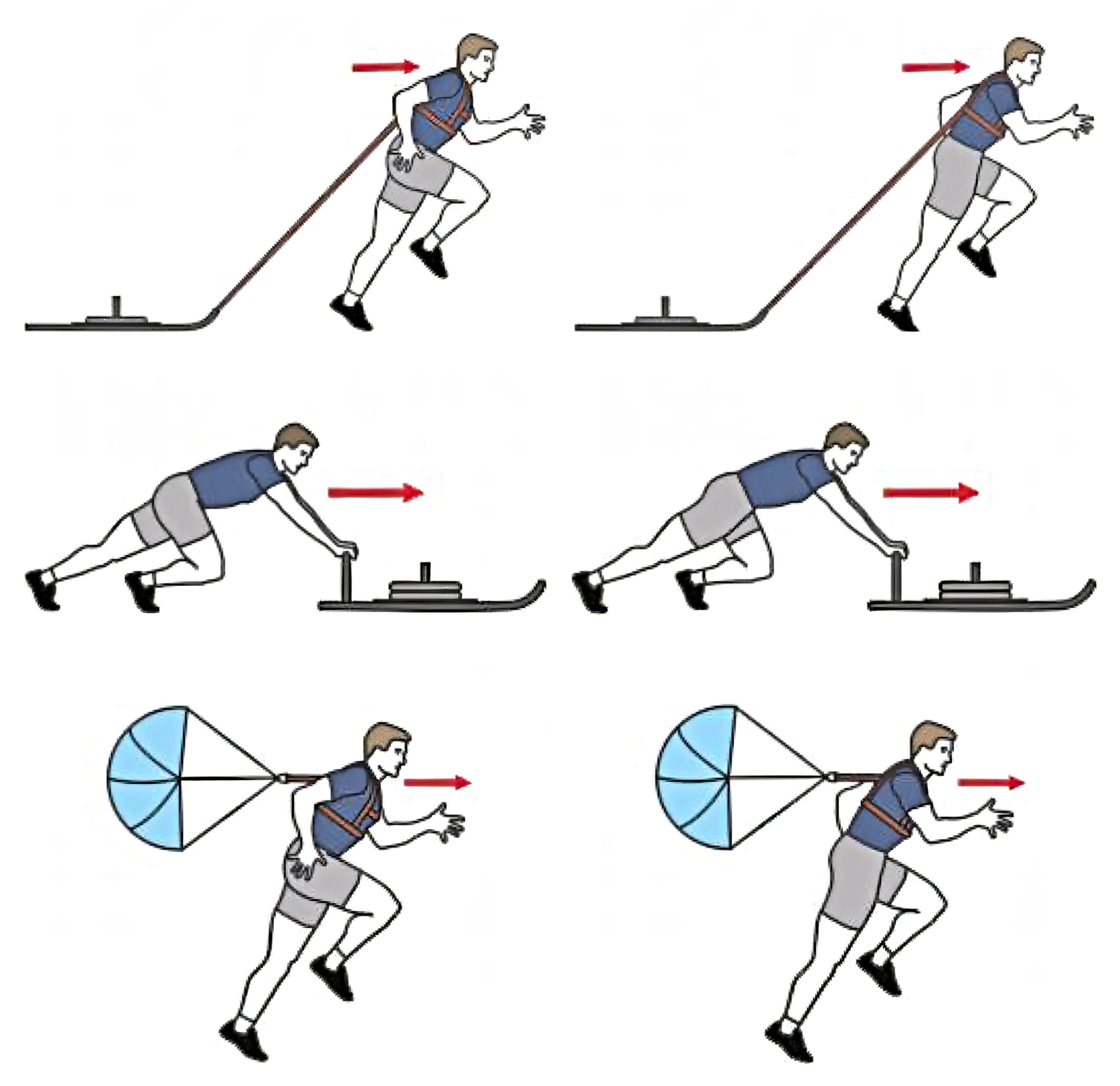

When I coached at the Air Force Academy in the 1980s, we began using contrast training with our football team. We had athletes first pull a sled and then perform short sprints without it. During this time, speed parachutes gained popularity as a contrast training method (in fact, in the early 1990s, BFS worked with Dr. Tabachnik to promote this product, which he introduced to the US market). These devices featured a quick-release mechanism that allowed athletes to disengage the chute mid-stride. Later, push sleds such as the Prowler® became a popular resistance running tool. To perform contrast training with a push sled, the athlete briefly pushes the weighted sled, then releases their grip and sprints past it.

In weightlifting, the intensity of a lift is determined by how close the weight lifted is to your one-repetition maximum. If you can lift 100 pounds for one rep and do so, your intensity is 100 percent. Conversely, if you lift 90 pounds for four reps, you might feel like you’re working harder, but your intensity remains at just 90 percent.

As a general guideline, weights of at least 85 percent of your one-repetition maximum (1RM) represent an intensity level that will recruit high-threshold motor units. Completing 10 reps represents approximately 75 percent of your one-repetition maximum, which will not significantly develop the fast-twitch fibers. This relationship has important implications for program design for athletes who want to run faster, jump higher, throw faster, kick further, and become more powerful overall.

Having addressed the science stuff, let’s now look at two types of wave loading that can be performed in the weightroom.

Wave Loading Method #1: Back-Off Sets

Understanding the history of wave loading is essential for appreciating its value. This brings us back to Nikolov, one of three Bulgarians to win a gold medal in the 1972 Olympics. These victories helped Bulgaria upset the heavily-favored Russians for team time, which shocked the Iron Game community.

I say “shocked” because the Russians were the dominant force in weightlifting in the 1960s. Reasons for their success included substantial financial support from their government and a large genetic pool of reportedly over 100,000 competitor weightlifters. In contrast, the Bulgarian weightlifting program operated with limited financial resources and had only a few thousand weightlifters. However, these disadvantages were offset in 1969 when Ivan Abadjiev became the head coach.

Under Abadjiev’s leadership, the Bulgarians became a weightlifting powerhouse for two decades, producing 9 Olympic and 57 World champions. I wanted to learn more.

With the wave loading method I read about in Muscle Builder/Power, Nikolov would work up to a maximum or near-maximum in a lift, then decrease the weight to complete his repetitions with heavier weights than could be utilized in a conventional pyramid approach. We can call this approach “back-off” sets, although another name could be “reverse pyramid.”

Besides recruiting fast-twitch fibers, the heavy singles raise the “shutdown threshold” of a tension/stretch receptor known as the Golgi tendon organ (GTO). An example of the shutdown threshold occurs during an arm-wrestling match when the weaker opponent’s arm suddenly slams onto the table, safeguarding their muscles from tearing.

Here are two contrasting workouts showing how back-off sets allow athletes to lift heavier weights for multiple repetitions. Both methods prescribe “working sets” of three sets of three reps.

| Set | Conventional Approach | Back-Off Sets |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | 50% x 5* | 50% x 5 |

| 2 | 60% x 4 | 60% x 4 |

| 3 | 70% x 3 | 70% x 3 |

| 4 | 80% x 3 | 80% x 2 |

| 5 | 85% x 3 x 3 | 85% x 1 |

| 6 | None | 90% x 1 |

| 7 | None | 95% x 1 |

| 8 | None | 87.5-90% x 3 x 3 |

*Percent is the percent of 1-repetition maximum

As you can see, the back-off series allowed the athlete to lift significantly heavier weights for the working sets. It accomplished these results without a substantial increase in volume (+3 reps), leading to a high level of fatigue that could affect the amount of weight lifted. The back-off set approach also comes with a physiological bonus.

After lifting your maximum or close to it, the bar feels lighter when you reduce the weight to perform your working sets, boosting your confidence to complete more reps. This is akin to using chains attached to a barbell during squats. As the lifter bends their knees, the chain links begin to rest on the floor, and the resistance decreases, giving the athlete confidence to complete the lift or squat more deeply.

Rediscover Wave Loading: Program Design for Speed and Power Share on X

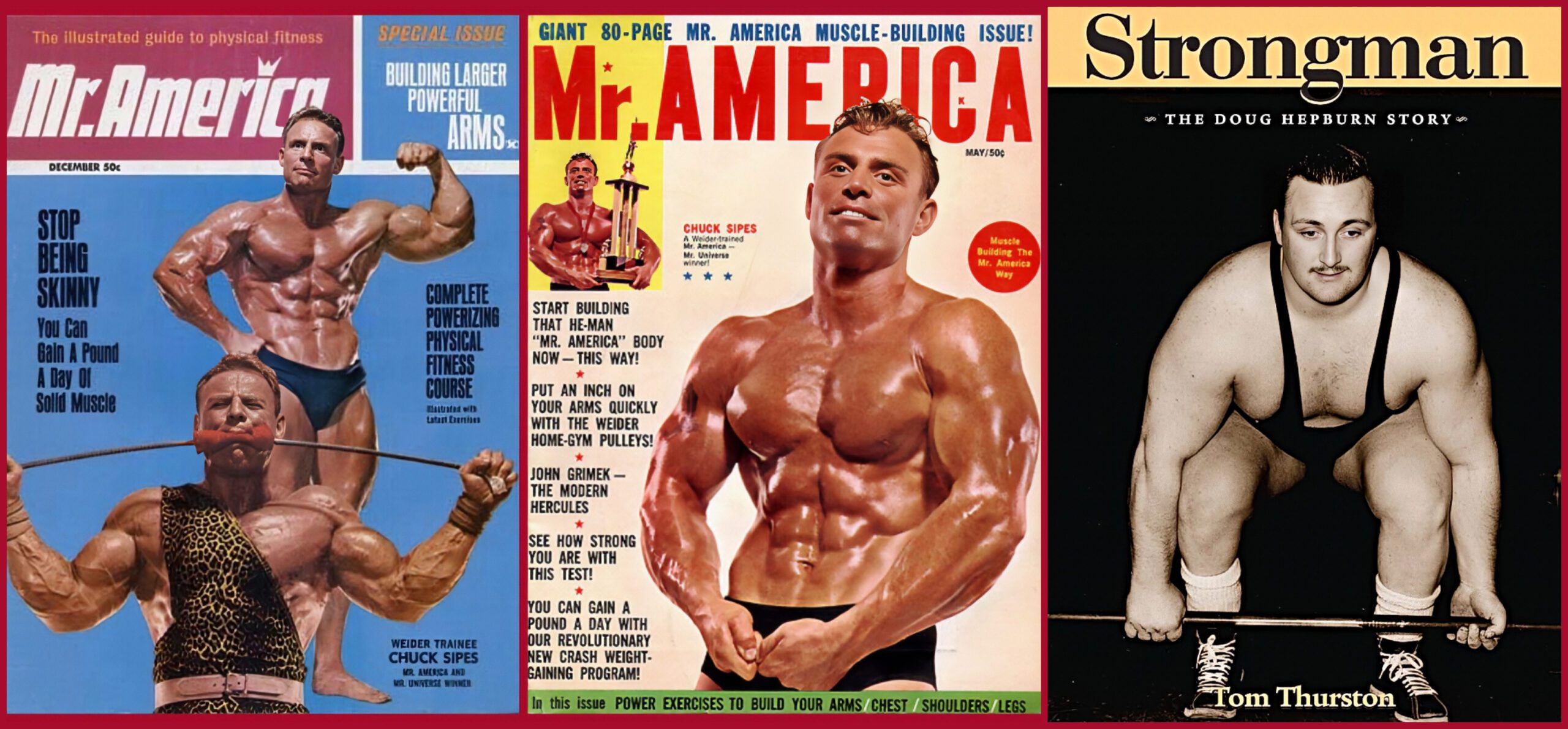

Giving credit where it’s due, legendary strength athlete Doug Hepburn and bodybuilding champion Chuck Sipes practiced forms of contrast training. Hepburn broke eight world records in weightlifting and won the 1953 World Championships. He was the first man to bench press 500 pounds and did a one-arm military press of 200 pounds. Sipes was the 1960 IFBB Mr. Universe and was as strong as he looked. At a bodyweight of 220 pounds, Sipes bench pressed 570 pounds, squatted 600, and did a “cheat” barbell curl with 250.

Hepburn would perform low reps with maximal weights on one exercise, then decrease the weight and get in his reps. Sipes would support heavy weights in the lockout or near-lockout positions. For example, during a deadlift workout, he might perform standard deadlifts, deadlifts from below the knees, and conclude with deadlift holds. In one example, he would perform deadlift holds for six sets, holding the weight for one minute per set. (Note: The issue with using isometrics for contrast training is they are especially fatiguing; however, to be fair, Sipes said he used heavy supports for tendon and ligament strength.)

While back-off sets are effective, another wave-loading approach allows athletes to train at even higher intensity levels.

Wave Loading Method #2: The Abadjiev Method

In 2013, I attended a seminar by Coach Abadjiev. Much of his lecture discussed concepts such as the neurological adaptations caused by the Protein Memory Hypothesis. Abadjiev said protein memory deals with how the protein strands synthesized by mRNA with 90 percent lifts differ from those synthesized by 95 percent lifts…ah, sure. Anyway, the point was that to achieve physical superiority, Abadjiev believed that weightlifters must train as heavy as possible as often as possible.

The next day I spent an hour with Abadjiev in our gym, asking him questions and observing him train one of his lifters. I asked him about using weights in the 75-85 percent range to improve speed, which seemed a popular approach by Russian weightlifters. He responded: “I don’t want my weightlifters to lift light weights fast—I want them to lift heavy weights fast!” This idea is similar to the methods promoted by Charlie Francis, who saw little value in having sprinters perform longer distance runs for sprinters. Okay, now for the details.

When aiming for a maximum single, a common approach for an athlete is as follows:

50% x 5

60% x 3

70% x 2

80% x 2

85% x 1

90% x 1

95% x 1

Go for a maximum

Although this method prepares an athlete for a maximum lift, Abadjiev discovered how to enable his athletes to lift even heavier weights. Specifically, he had his athletes work up to a maximum single, reduce the weight, and then work back up to another max. His athletes would often perform several of these waves.

Rediscover Wave Loading: Program Design for Speed and Power Share on X

Often, particularly with advanced athletes, wave loading enables athletes to surpass the results of previous attempts, increasing the training stimulus. Here’s an example, using 100 pounds as a personal best for a power clean:

| 1st Wave | 2nd Wave | 3rd Wave |

|---|---|---|

| 50 x 5 | 90 x 2 | 92.5 x 1 |

| 65 x 4 | 95 x 1 | 97.5 x 1 |

| 80 x 3 | 97.5 x 1 | 100 x 1 |

| 90 x 2 | 100 x 1 | 102.5 x 1 |

| 95 x 1 | ||

I first tried Abadjiev’s wave-loading method with a former D1 college lineman who had decided to focus on weightlifting. I watched him compete in a local meet—where he made all his attempts and snatched 230 pounds—and then invited him to our gym. A week later, he performed several waves in a single workout and finished with 255 pounds.

Here’s a closer look at this method in action. Video 1 (below) shows Nikki, a former D1 field hockey player, performing the power clean. On her first wave, she easily succeeded with 65.5 kilos (144 pounds). She jumped to 70.5 kilos, but could only manage a high pull. We lowered the weight to 66.5, which she made, followed by successes at 67.5, 69.5, 70.5, and 71.5 (157 pounds). The result is that the second wave enabled Nikki to increase the intensity of her workout by about nine percent.

Video 1. A real-world demonstration of how wave loading can enable athletes to use heavier weights for a given workout.

Getting the Most out of Wave Loading

Although I could write a book wave loading, here are ten guidelines I’ve found effective for getting the most out of this remarkable training method.

1. Perform wave loading exercises first in a workout.

You should schedule wave loading at the beginning of a workout when you are fresh and can put the most effort into these sets. Expanding on this idea, legendary strength coach Charles Poliquin said that fatigue changes the pH levels in the blood, affecting the muscles’ ability to contract.

[bctt tweet=”Schedule wave loading at the beginning of a workout when you are fresh and can put the most effort into these sets—Charles Poliquin said that fatigue changes the pH levels in the blood, affecting the muscles’ ability to contract.”]

2. Reserve wave loading for multi-joint movements.

To stimulate maximum muscle mass development, a bodybuilder might perform exercises to target each of the three heads of the triceps: long, medial, and lateral.

A general rule for someone who isn’t a bodybuilder is, “If you take care of the larger muscle groups, the smaller ones will take care of themselves.” Therefore, athletes who perform dips, which work all three heads of the triceps, don’t need to perform finishing sets of rope triceps pressdowns. Similarly, because so many sets are performed with this method, using it exclusively with multi-joint movements reduces your workout time.

3. Perform wave loading sparingly.

Wave loading is a highly taxing training method that necessitates longer recovery times. For instance, completing a wave loading session with squats on Monday can result in lingering fatigue that would impact your ability to lift monster weights on Wednesday.

You must also consider that not all exercises have the same recovery periods. The recovery period for a squat may be longer than for a military press, and the recovery period for a deadlift may be longer than for a conventional deadlift.

A conventional hex bar deadlift is performed with a more upright spine than a conventional deadlift, which might lead to a shorter recovery period. Additionally, a high hex bar deadlift has a significantly shorter range of motion, which should lead to an even shorter recovery period.

4. Cycle wave loading into long-term planning.

To get the most out of wave loading, scheduling it at the most appropriate times is essential. Because it is so physically demanding, you would not perform wave loading a few days before a major athletic competition.

Here is a general outline of a four-week weightlifting cycle inspired by Coach Spassov that I’ve used with several of my competitive weightlifters:

Week 1: Deloading

Week 2: High Volume

Week 3: High Intensity

Week 4: Peaking

In this example, back-off sets (higher volume) could be performed during Week 2 and the Abadjiev Method (higher intensity) during Week 3.

5. Focus on low reps for speed and power.

As Ross explained when he worked with Allyson Felix, activating these high threshold motor units in the weightroom could increase stride length as long as there are also minimal increases in bodyweight. Let me share three real-world examples of weightlifters who dramatically increased how much they lifted over several years while remaining in the same bodyweight division.

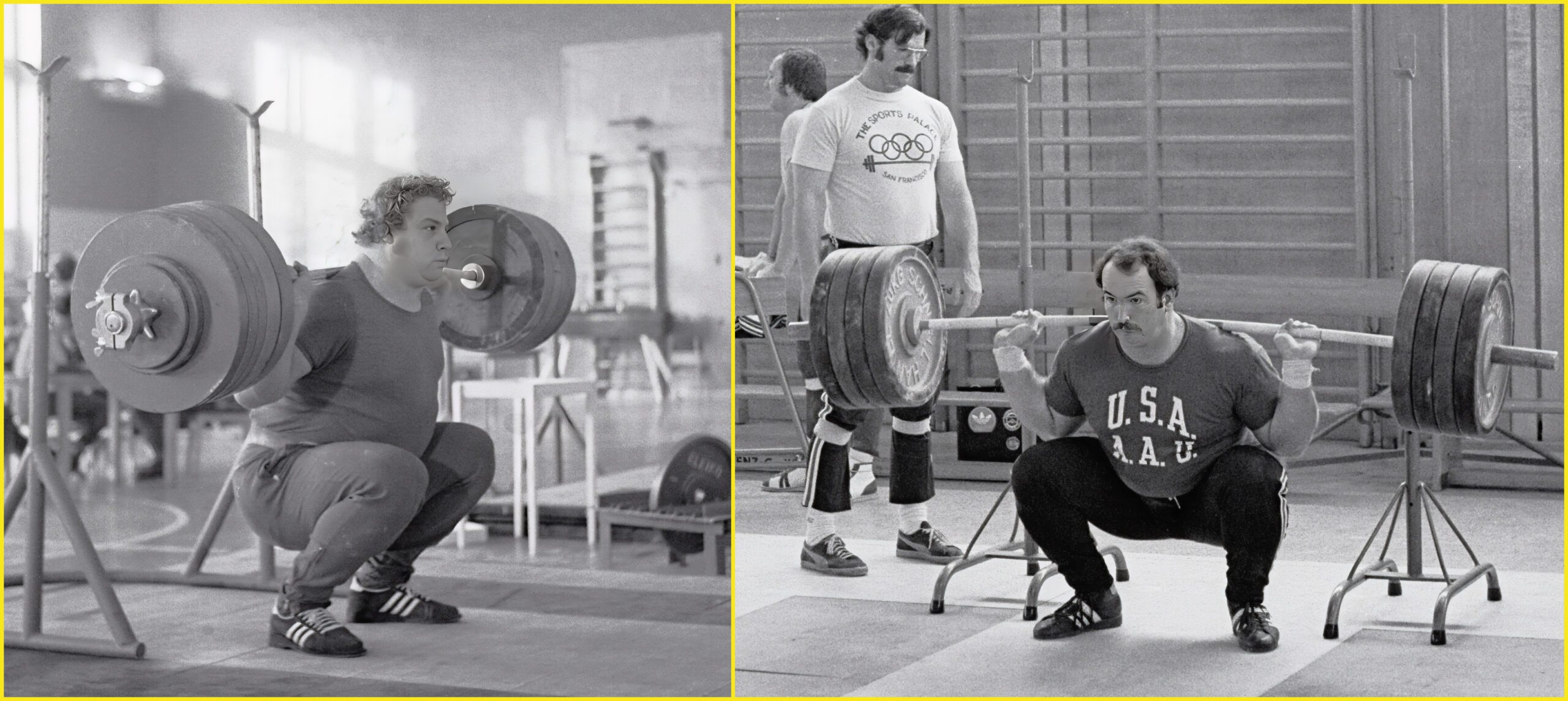

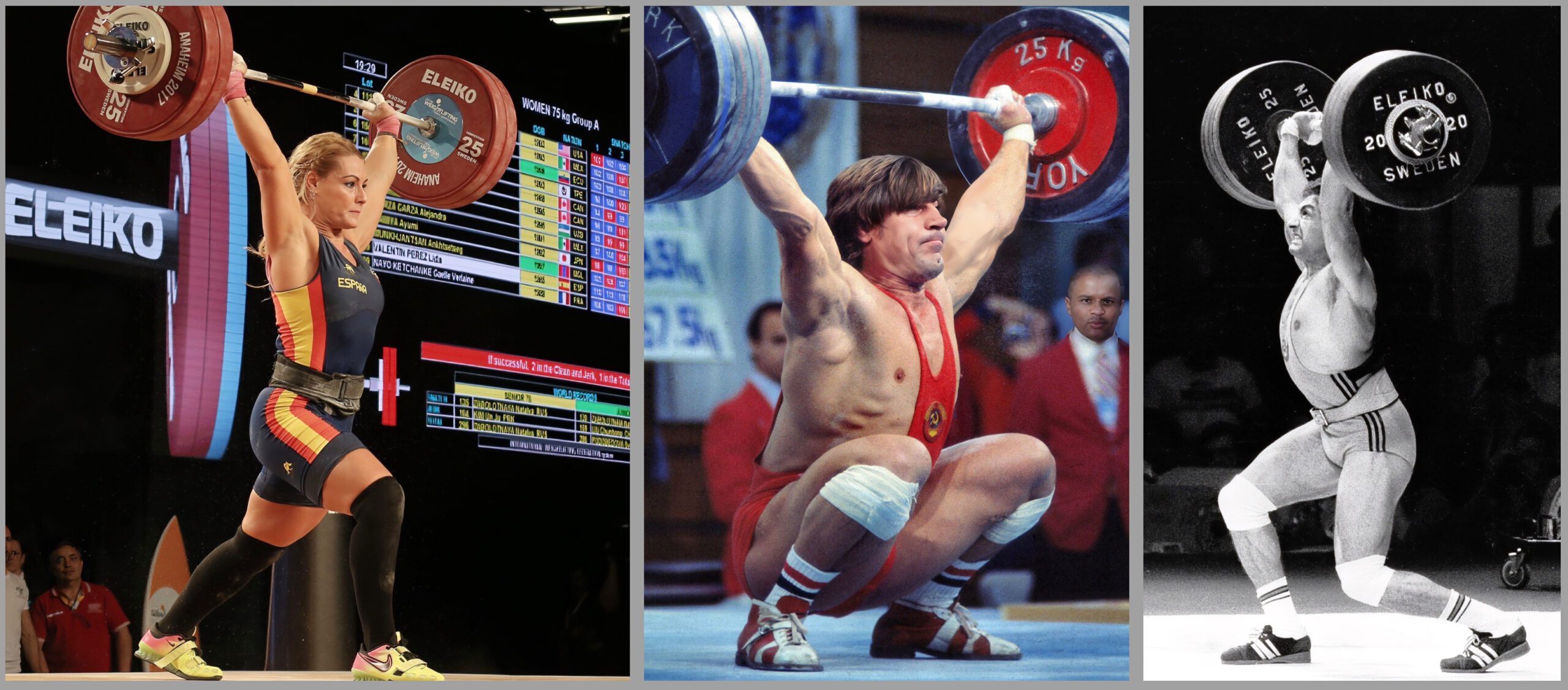

Image 7 below shows three weightlifters who won Olympic gold. The men’s first and last lifts in this table represent world records, so they all competed at the highest levels and possessed superior technique. All three lifters’ body weight remained the same despite spans of six, eight, and nine years. By focusing on training the high-threshold motor units, they got stronger without getting bigger.

| Name | BW | Year | Snatch | Clean and Jerk |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| David Rigert | 198 | 1970 | 357 | —– |

| David Rigert | 198 | 1971 | —– | 457 |

| David Rigert | 198 | 1978 | 397 | 488 |

| Yuri Vardanyan | 181 | 1978 | 375 | 462 |

| Yuri Vardanyan | 181 | 1984 | 397 | 493 |

| Lidia Valentin | 165 | 2005 | 229 | 257 |

| Lidia Valentin | 165 | 2014 | 273 | 324 |

Notes:

— BW = Bodyweight

— All weights in pounds

— Lidia Perez Valentin’s initial lifts were performed at the Junior World Championships

I should point out that Rigert was known for exceptional sprinting ability (reportedly running 10.4 in 100m) and Vardanyan for his jumping ability, as he could reportedly standing long jump 12.1 feet and high jump seven feet using a three-step approach and forward takeoff. There are YouTube videos showing Vardanyan performing remarkable displays of his jumping ability.

6. Use longer rest periods.

The nervous system may need 5-7 times more rest than the muscular system—you wouldn’t rest for 15 seconds between sets of 50-meter sprints if speed development is the goal. For lifting, rest periods should range from 180 to 300+ seconds, depending on the training priority and repetition intensity chosen. Here is an example, using the 2nd wave in the previous example:

| Percent of 1RM | Rest (seconds) |

|---|---|

| 90 x 2 | 180s |

| 95 x 1 | 240s |

| 97.5 x 1 | 300s |

| 100 x 1 | 300s |

| 300s | |

| Begin 3rd wave |

An exception would be if you used wave loading with supersets involving two exercises, such as a push press and deadlift. Rest periods with these protocols could be shortened as returning to the first set takes longer.

7. Use a rep range for back-off sets.

One challenge in designing workouts is that numerous variables influence an athlete’s performance in a specific session, so a coach can only make an educated guess. (Fun Fact: One college strength coach told me he intentionally kept Monday workouts light because many of his athletes were often hungover from partying the night before!)

Let’s say an athlete is scheduled to perform three sets of three reps using 85 percent of their one-rep max. In this case, 85 percent might be too light or too heavy to achieve optimal loading, so the odds of a coach guessing the optimal weight are 1:3.

Instead of prescribing a single repetition number, use a rep range, such as 2-4, to optimally challenge the athlete.

One highly effective variation of back-off sets for this purpose—and a favorite of Coach Poliquin—is the 1-6 Method. To the best of my knowledge, Dragomir Cioroslan, an Olympian and the coach of 1984 Olympic Champion Nicu Vlad, created it.

In superset style, the 1-6 Method alternates between sets of one repetition and six repetitions. You start with about 90 percent of your 1RM for the first set and 75 percent for the set of six, increasing these percentages each set. After each set, the athlete rests for about four minutes. The weight for each superset increases.

After warm-up sets, here is how such a workout could progress for an athlete who squats 300 pounds:

Set 1: 1 rep with 270 pounds

Set 2: 6 reps with 225 pounds

Set 3: 1 rep with 275 pounds

Set 4: 6 reps with 230 pounds

Set 5: 1 rep with 280 pounds

Set 6: 6 reps with 235 pounds

Although this topic is beyond the scope of this article, my colleague Paul Gagné uses a form of the 1-6 Method with isoinertial (flywheel) training, alternating heavy disks with lighter ones. He also performs more repetitions, because achieving optimal speed requires a few “garbage reps” to tighten the belt’s slack.

8. Be conservative at first.

The number of waves an athlete can perform is influenced by their conditioning level. While it’s impressive to hear about the accomplishments of elite weightlifters breaking PRs on multiple waves, a beginner should start with only one wave. As a general guideline, you are probably doing too many waves if you do not exceed the previous maxes on your last wave.

9. Use wave loading to correct errors in weightlifting exercises.

Poor technique often hinders the performance of heavy lifts or partial movements, such as the snatch. Wave loading is an effective method for correcting errors that cause athletes to miss maximal weights. Also, with highly technical lifts such as the snatch, the improvements in a single wave loading workout can often be exceptional—backing off with lighter sets may enable the athlete or their coach to figure out how to correct the fault.

Rediscover Wave Loading: Program Design for Speed and Power Share on X

Video 2. A real-world demonstration of how wave loading can enable athletes to correct technique faults in the snatch.

In Video 2, you’ll see Lisa, a former collegiate tennis player, performing snatches. She made a shaky snatch with 41 Kilos (90 pounds) and then missed 42 kilos twice. On the second wave, she dropped to 37 kilos, then made 39, 42, 43, and 45 kilos (99 pounds), approximately a 10-percent improvement. She even seemed a little faster.

One more example. Athletes often miss a maximum power clean because they begin with the bar moving forward, away from the body’s center of mass. Once the athlete reaches their peak on the first wave, they can reduce the weight and perform a few light clean deadlifts to the knees to strengthen the optimal bar path. After a few of these sets, the athlete would work back up in the power clean to a new maximum.

10. Introduce variety into waves with similar exercises.

Similar exercises can be integrated into a wave-loading series to introduce variety into a workout. For example, you might perform two waves of hex bar deadlifts using the low handles and switch to the high handles for the third wave. This method ensures that the final set involves heavier weights, which is motivating for the athlete.

Wave loading is a proven training method for increasing strength and explosiveness in athletes. Follow these guidelines to see what this high-intensity training method can do for you!

References

Tabachnik, Ben. Personal Communication. January 1994

Weyand PG, Sternlight DB, Bellizzi MJ, and Wright S. “Faster top running speeds are achieved with greater ground forces not more rapid leg movements.” Journal of Applied Physiology (1985). November 2000;89(5):1991-9.

Stone MH, Sands WA, Pierce KC, Ramsey MW, Haff GG. “Power and power potentiation among strength-power athletes: preliminary study.” International Journal of Sports Physiology and Performance, March 2008;3(1):55-67.

Ross, Barry. Underground Secrets to Faster Running, BearPowered, November 2, 2005. [Also, a non-dated article by Ross called “The Holy Grail in Speed Training.]

Shepard, Greg. “Sprint Chute™ Training Guidelines.” Bigger Faster Stronger, Spring 1994.

Thurston, Tom. Strongman: The Doug Hepburn Story, Ronsdale Press, August 16, 2003.

Weis, Dennis B. “Echoes from the Power Storm that was Chuck Sipes!” Critical Bench.com, 2011.

Abadjiev, Ivan. Personal Communication, May 19, 2013

Francis, Charlie and Coplon, Jeff. Speed Trap: Inside the Biggest Scandal in Olympic History, St Martin’s Press, January 1, 1991.

Thibaudeau, Christian. “The 1-6 Loading Scheme for Strength and Size.” Thibarmy.com, April 17, 2018.

Gagné, Paul. Personal Communication, December 15, 2024.