When it comes to the box squat, there is no gray area in the field of strength coaching. You either love it or you hate it. The athletic fitness training company Bigger Faster Stronger (BFS) loves it, and their coaches have taught the exercise for 44 years in over 10,000 clinics, covering every state of the country. Having worked for BFS, I can tell you why they believe this exercise has value for virtually all athletes, not just those involved in the Iron Game.

Let’s make it clear that BFS does not claim to have invented the box squat, although there is debate about who did. There is a good case that 1946 AAU Mr. America Alan Stephan created it, while others say that Polish athletes were taught it in the mid-1900s. The answer may be that several people came up with the exercise at the same time, not knowing about others who were also experimenting with it.

Many strength coaches believe that box squats have little value for athletes because they’re performed through a partial range of motion. If partial range exercises are so bad, why do these same coaches have their athletes do bench presses? The arms don’t come together at the top of the movement, so the pectoral muscles can’t fully contract, and the barbell stops at the chest, preventing a full stretch of these muscles.

The truth is, partial range exercises provide many benefits. We’ll get into a few of these in this post.

Background on Bigger Faster Stronger and Box Squats

The inspiration for the BFS workout that includes box squats began about 50 years ago when BFS coaches studied the training of several of the best throwers in the world. These men were impressive not just because they were big and strong but also due to their athleticism, speed, and jumping ability.

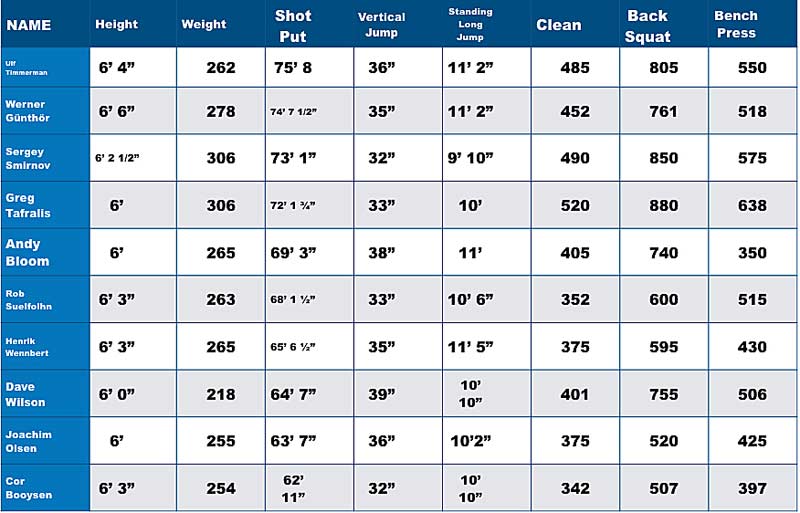

Many throwers weighing over 270 pounds could run the 40-yard dash in under 4.6 seconds and had a vertical jump of 35 inches or more. In fact, in the ’60s and ’70s, coaches from the former Soviet Union would visit the United States to study these physical phenoms. Need more convincing? Table 1 highlights some of the strength and jumping performances of several top shot putters.

Two US throwers who were especially impressive—and whose training methods inspired the development of the BFS training system—were Jon Cole and George Frenn. Cole and Frenn toured Europe as members of the USA Track and Field squad and often trained together. These powerful giants were multiple-sport athletes and the closest thing you could find to Marvel superheroes at the time.

Cole threw the discus 231 feet, put the shot 71 feet 4 inches, and threw the javelin 241 feet. Weighing 258 pounds, he ran the 100-yard dash in 9.9 seconds in a sanctioned AAU event, threw a baseball 435 feet, and kicked a football 68 yards.

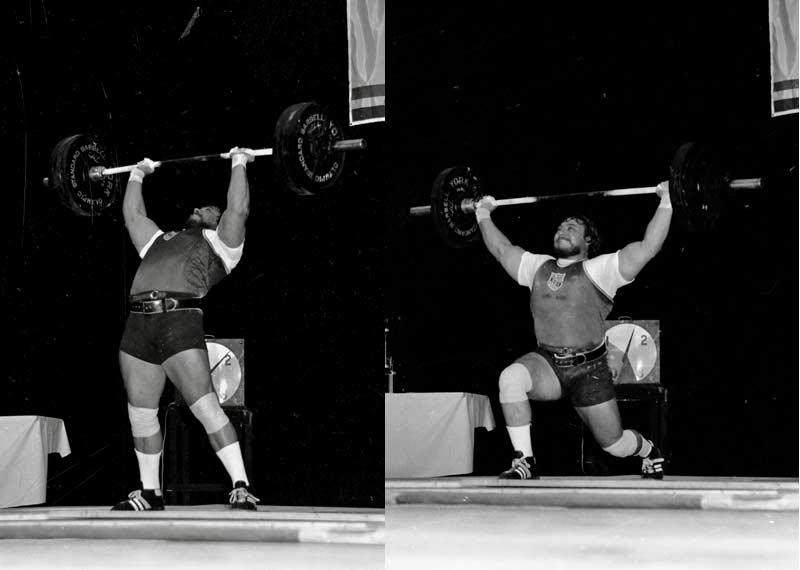

In powerlifting, without the supportive gear used today, Cole became the first man to total over 2,300 pounds. His best official lifts, performed in 1972 with only elastic bandages for his knees and a weightlifting belt, include the following: squat, 905; deadlift, 885; bench press, 580; and total, 2,370. In weightlifting, Cole competed in the 1972 Olympic Trials and made the following bests: Olympic press, 430; snatch, 340; clean and jerk, 430; and total, 1,200.

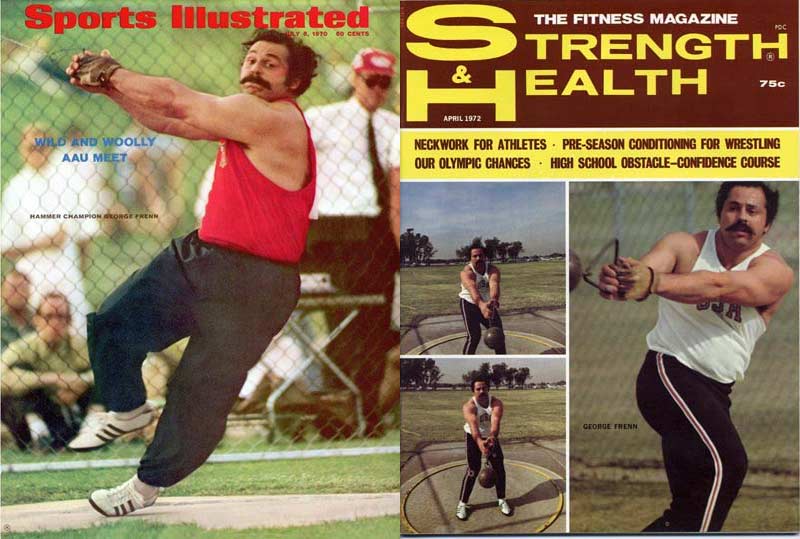

Frenn was a hammer thrower who competed in the 1972 Olympics, just missing out on the 1968 team when he placed fourth in the trials. He had a personal best of 232.5 feet, established world bests in the heavier hammers, and was one of the few field athletes to appear on the cover of Sports Illustrated.

Equally impressive was Frenn’s strength, which enabled him to break world records in powerlifting. At a bodyweight of 242 pounds, Frenn officially squatted 853 pounds, deadlifted 815 pounds, and—although he didn’t emphasize the lift because he felt it didn’t help his throwing much—a 540 bench.

Cole’s athletic accomplishments convinced the BFS coaches that virtually all athletes could benefit from focusing on a combination of powerlifting and weightlifting exercises, but it was Frenn who sold BFS on the box squat.

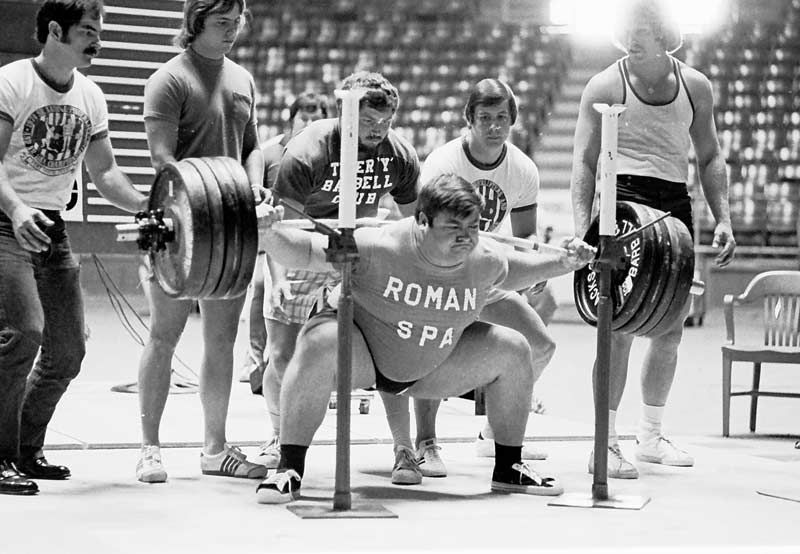

Since these were the days before the Internet, BFS learned about Frenn’s training from first-hand accounts of a BFS coach who watched him train as well as articles Frenn wrote and those by other writers in the Iron Game. In one article, Frenn said he would squat on Tuesday and Saturday and perform two types of box squats: the high box squat and the low box squat.

Frenn performed his high box squat on a 20-inch tall box. This height enabled him to use considerably more weight than his competition best. He reportedly used over 1,000 pounds with this exercise. His low box was 14-inches tall, forcing him to use weights below his competition best squat. Of course, Frenn said that for anyone who wants to try these exercises, the exact height of the box depends upon the height of the athlete.

Box Squat Variations and Safety

George Frenn performed a variation of the box squat where he rocked back on the box, lifting his feet off the floor before slamming them down hard as he drove upward to the finish. For safety reasons, BFS doesn’t recommend this advanced variation, especially when working with large groups of young athletes. That said, if a coach can competently teach this method and can adequately supervise their athletes, there is little cause for concern. As is often said in the field of coaching young athletes, “There is optimal training, and there’s reality!”

As for the risk of injuring the spine with the box squat, consider that BFS once consulted with Dr. Greg Motley, an orthopedic surgeon who specializes in arthroscopic procedures at Southeastern Sports Medicine in Asheville, North Carolina. Motley’s athletic career caused him to have six surgeries and left him with two degenerated disks, “So I would know if there was increased pressure on the lumbar spine,” Motley said.

Not only did Motley perform the box squat with no pain, but he also ended up endorsing the exercise. “I went up pretty heavy that day, a lot heavier than I thought I could go—and I hadn’t squatted in 10 or 12 years. I think that it’s critical with the box squat—with all squats—that you have good technique and alert spotters. That being said, I think the box squat is a very, very good exercise.”

Before describing how BFS teaches the box squat, I must mention Westside Barbell’s Louie Simmons. Frenn was a member of the original Westside Barbell club run by Bill “Peanuts” West, and Simmons took on the name as a tribute to this Iron Game pioneer. Simmons advocates the box squat but promotes a wide stance variation designed to reduce the work of the quads while increasing the work the posterior chain muscles. If you want to learn the Westside box squat technique, you should go to the source and check out the material produced by Coach Simmons.

Powerlifters often perform wide stance squats (with the bar low on the back and a large forward lean), so the box squat with a wide stance has a better carryover to the sport of powerlifting. There is a case to be made for athletes to occasionally perform wide stance squats, as often in sports the legs are positioned outside the shoulders.

Why Box Squat?

From a BFS perspective, the most important reasons for doing box squats are to get stronger during the season and to stay fresh for competition. As a bonus, the squat helps motivate athletes to use heavier weights and set personal records. Let me expand on these benefits.

The reality of high school strength coaching is that many coaches fear the weight room. They’re afraid their athletes will get sore from lifting and not be able to practice hard or compete well. I’ve learned from working with high school coaches in my area that some coaches (not all) believe there’s little value in having sprinters lift at all. Here are some typical comments I’ve heard from sprint coaches, from the first meet to the last during the indoor season:

- Got the first meet of the season, and we want to show we mean business this season. Back off a bit with the weights.

- Got the first invitational meet of the season. There’s FAT timing, and college scouts will be checking us out. No legs on Thursday.

- Got an important dual meet coming up, and we need those team points. No lifting on Thursday.

- Got a dual meet against our school rival—we really need this. No lifting the entire week!

- Got the Class A Championships. Go light.

- Got the Division Championships. No lifting on Thursday.

- Got finals this week. Workouts are optional.

- Got the State Championships. No lifting.

- Got the New Balance Indoor Nationals. No lifting.

After their last meet, coaches want their athletes to take a few weeks off before starting back for the outdoor season. Translation: no lifting! And when the outdoor season starts, we’re back to the same recommendations (but focusing on the New England Championships). Again, they’re afraid of the weight room, and some coaches see no value in weight training. In fact, a local sprint coach bragged on social media about how one of his athletes broke a personal record in the 100m without touching a weight.

High school sprinters will spend two-thirds of their school year getting weaker or, at best, maintaining. Share on XEven if you can convince a coach to allow their athletes in the weight room, the second workout of the week will nearly always have to be light, and it’s difficult to make strength gains with these restrictions. Putting it another way, sprinters will spend two-thirds of their school year getting weaker or, at best, maintaining. Knowing these problems, where does the box squat fit in?

The box squat doesn’t create the fatigue of a conventional squat because it stops the eccentric motion of the lift and is performed through a partial range of motion. Yes, this type of movement increases the concentric muscular work of the quads (because much of the energy stored from the descent dissipates and the stretch reflex is inhibited), but a concentric contraction doesn’t produce the amount of soreness of an eccentric contraction.

Thus, an athlete can lift heavy the day before a competition, or even immediately before a hard practice, without the workout adversely affecting performance. BFS has also found that the second workout helped athletes to get stronger during the season.

Another benefit of performing heavy squats through a partial range of motion is the mental preparation for achieving personal records. Let’s say an athlete’s best squat is 200 pounds, and they regularly perform box squats with 250-275 pounds. When they attempt a new personal best, such as 210 pounds, this weight will feel lighter when they place the bar on their shoulders, giving them the confidence to “go for it!” Using heavier weights also takes advantage of post-tetanic potentiation (PTP).

Box squats mentally prepare athletes to use heavier weights and set personal records. Share on XPTP states that we can achieve a more powerful muscular response if a strong muscular contraction precedes it. For example, if you lift several heavy boxes and then immediately lift a lighter one, the lighter one will feel especially light (and may even fly out of your hands) because the same fast-twitch fibers needed to contract when you lifted the heavy boxes remains recruited.

To take advantage of PTP, you can have an athlete perform box squats and then immediately do box jumps. Coaches at BFS clinics have an athlete perform a vertical jump, do a box squat workout, and then perform another vertical jump. Without fail, the second jump is always higher.

There is also the concept of sport specificity as it relates to first step quickness. Some activities in sports start from a motionless position without involving the stretch reflex, such as when a sprinter starts or a football lineman jumps into action after the ball is snapped. A box squat teaches the athlete to initiate movement quickly.

Finally, there is the mental benefit. Having an athlete start a competition knowing that the day before they lifted a monster weight in the box squat reinforces their belief that they are strong—brutally strong. This gives the athletes confidence. At least, more confidence than they would have if the day before they reduced the amount of weight they used in half. Or, worse, didn’t train at all.

I should note that the box squat is not a mandatory exercise in the BFS program. If a coach wants their athletes to perform another squat variation, even the Bulgarian lunge, that’s fine.

BFS Box Squat Technique

What follows is the BFS method to teach the box squat. First, BFS recommends that athletes perform the box squat inside a power rack with the safety supports set high enough so the athlete can easily dump the weight forward without the bar moving more than a few inches. You can see this set-up in the first video below.

Next is the issue of what type of box to use. Although a sturdy wood or metal box is acceptable, it’s better to have some cushioning on the surface. BFS found that with wood and metal surfaces, athletes tend to plop down, causing the spine to flex and possibly cause injury. Having some cushion gives the athlete feedback so they can settle down on the bench. Also, adjustable boxes are a good investment when training large groups of athletes.

The height of the box is determined by how much weight the athlete will use. Set the box so that the top of the thighs are slightly above parallel. A good general guideline is to start with the thighs 1-2 inches above parallel. When an athlete can use 100 pounds over their best regular squat, lower the box slightly.

Video 1. The set-up for the BFS box squat.

Spotting is the next issue. BFS prefers using three spotters, one on each side and one in back. The spotters keep their hands on the bar at all times to ensure that the weight is secure on the shoulders and to help remove and replace the bar on the supports.

To perform a box squat without spotters, use a power rack with the safety supports set just below the lowest position, so the barbell reaches the bottom position. If the athlete fails, however, they would have to lean forward to allow the bar to rest on the supports. For some people, this action places adverse stress on the spine.

Video 2. How to spot the BFS box squat.

Many injuries in the squat occur when removing and replacing the bar on the supports and not during the lift. If you’re using bands, a back spotter is especially important because bands decrease the stability of the exercises. Squatting with bands is an advanced method that needs to be supervised by an experienced coach. Chains are better for large groups of athletes because they provide more stability, and athletes are less likely to be thrown off balance.

The start position of a box squat is the same as a regular squat; we want the strength developed with this exercise to transfer directly to the regular squat. The athlete positions their feet on either side of the box, bends from the knees and hips, and slowly sits down on the box, being careful not to plop down hard.

When the athlete touches the box, they shift back slightly to reduce the compressive stress on the spine. Keeping the back tight, they shift slightly forward from the hips and then drive up explosively. A useful cue is the BFS 3 S’s: down slow, sit, and settle. Check out the final video to see a demonstration.

Video 3. Performing the BFS Box Squat.

Finally, BFS does not recommend learning how to box squat from reading an article or watching a video—there is no substitute for hands-on teaching from an experienced coach.

It’s been said that all things being equal, the stronger athlete usually wins—so why train your body to be weak? Instead of hopefully using a lifting program to maintain an athlete’s strength, use the BFS box squat to get stronger—from the start of the season to the finish.

Lead photo from Waterloo High School courtesy BFS.

Since you’re here…

…we have a small favor to ask. More people are reading SimpliFaster than ever, and each week we bring you compelling content from coaches, sport scientists, and physiotherapists who are devoted to building better athletes. Please take a moment to share the articles on social media, engage the authors with questions and comments below, and link to articles when appropriate if you have a blog or participate on forums of related topics. — SF

[mashshare]

References

Frenn, George. “Conditioned Legs Break Squat Records,” (1972), reprinted in The Tight Tan Slacks of Dezso Ban, July 13, 2016.

Shepard, G. and Goss, K. Bigger Faster Stronger, Human Kinetics, Inc.; Third Edition, July 31, 2017, pp. 66-67.

Siff, M. and Verkhoshansky, Y. Supertraining, 1999, 4th Edition, Supertraining International, Denver USA 1999, (1st edition, 1993), pp. 271-275.

Swinton, P.A., et al. “A biomechanical comparison of the traditional squat, powerlifting squat, and box squat.” Journal of Strength and Conditioning Research, 2012 July; 26(7), pp. 1805-6.

Verkhoshansky, Y. and Verkhoshansky, N. Special Strength Training Manual for Coaches, Verkhoshanky SSTM, 2011, pp. 110-113.