“Do you guys ever, like…deadlift?”

An intern once randomly asked me that question. In classic strength coach fashion, my answer was, of course, “It depends.”

We do. Kind of.

The single leg Romanian deadlift (SLRDL) has become a “main” lift within the program we run at PACE Fitness Academy. Is it the classic 1RM deadlift that goes on the big PR record board in the weight room? Nope. But it gives us what we need.

Plus, we don’t even have a record board.

What Is a ‘Main Lift’ Anyway?

I hear this question a lot. What is a main lift? What makes it so important? In some cases, these lifts are prioritized simply based on tradition. In other scenarios, the “main lifts” are standardized more for convenience. Many times, main lifts are the ones athletes are tested on. I always think of the “big 3”: bench, squat, and deadlift. These are the “A1’s” of the training session.

I see this through a bit of a different lens. KPIs (key performance indicators) are a hot topic or buzzword right now. This concept represents a new school version of “main lifts,” but expands beyond lifts and sometimes lifting in general. A KPI can be a lift, a sprint, a heart rate, whatever coaches decide works best for their athlete—but at their core, KPIs are quantifiable or manageable and used to track the performance of an individual.

The SLRDL transfers to other things that we track and manage much more closely, such as speed and unilateral power, says @JustinOchoa317. Share on XFor us, a main lift (or a KPI) is simply something that is a pillar of our program and pays dividends in other areas that we may be quantifying or testing. That’s where the single leg Romanian deadlift comes in. It’s quantifiable (if we want it to be). It can be managed. But most of all, it transfers to other things that we do track and manage much more closely, such as speed and unilateral power.

Single Leg Strength

I don’t want to reignite the whole bilateral versus unilateral debate—the great part about that discussion is that you don’t have to choose sides. Use one or the other where you see fit. In terms of the Romanian deadlift, we program both the bilateral and unilateral variations, but ultimately choose to favor the latter.

In my own training—and based on feedback from our athletes—the single leg version is a fan favorite. This response was initially what sparked us to explore if it can be considered a main lift; something worth prioritizing in a program just as coaches do with the trap bar deadlift, back squat, clean, or bench press.

The answer we’ve found so far is…yes. The lift is worth prioritizing.

In terms of the debate between unilateral and bilateral exercises, much of my thinking comes back to the concept of bilateral limb deficit (BLD). Here is an excerpt from a 2011 study in the European Journal of Applied Physiology by Kuranganti, et al:

“The bilateral limb deficit (BLD) phenomenon is the difference in maximal or near maximal force generating capacity of muscles when they are contracted alone or in combination with the contralateral muscles. A deficit occurs when the summed unilateral force is greater than the bilateral force. The BLD has been observed by a number of researchers in both upper and lower limbs, in isometric and in dynamic contractions. The underlying cause of the deficit remains unknown. One possible explanation is that the deficit occurs due to differences in antagonist muscle coactivation between unilateral and bilateral contractions.”

I first read Mike Boyle’s writing about this around 2015-16, and his blogs sparked my interest. At that time, I was struggling with some really bad long-term injuries and pain. Even as a strength coach, I had my fair share of rough years in my early 20s, where I blatantly ignored my own advice and just tried to lift as much as humanly possible—mostly on bilateral “main lifts.”

This was the first a-ha! moment for me.

It makes so much sense. If an athlete can split squat 350 pounds on each leg, an equal stimulus would be a 700-pound two-legged squat. First off, most athletes simply cannot do that. Secondly, most athletes simply do not want to even try to do that. And finally, the risk of 350 pounds versus 700 pounds is a lot lower and more manageable. When we’re talking about non-barbell sports, there is just a better bang for your buck to go with the unilateral choice.

Even without the science, I’m a big common-sense guy. This concept just really makes a ton of sense, so I adapted it from Mike Boyle and started to add my own flavor on a lot of unilateral work.

Another major a-ha! for me, ironically, was the common pushback I got when I shared this idea and some of my new methods with colleagues. I heard a lot of feedback from people afraid to let go of tradition, and I heard a lot of people who were incapable of opening their mind to new concepts (despite claiming to be “lifelong learners”). I heard a lot of “but we always used to just do this…” and “I was always taught that…”

Frankly, hearing that made me love going against the grain even more. For some reason, I took that as a sign to keep going toward the single leg, single arm work. I think tradition in S&C is great in a lot of ways, but those traditions can also hold us back by failing to adapt to the evolution of methods, education, and our athletes.

The third and final a-ha! came when I learned about Reflexive Performance Reset (RPR) in 2018. This is what connected all the dots for me. The basis of RPR practice is to learn to get better control of your nervous system so you can manage physical or mental stress to move and feel your best.

You do this through their “resets,” which are simple and effective drills athletes can do to optimize the neurological firing pattern of any chosen muscle group(s). It’s not a muscular release; it’s not trigger points; it’s not mechanical in any sense. It’s completely neurological. This was a huge paradigm shift for me.

I was honored to speak at the 2020 Arnold Sports Expo right before COVID-19 shut the country down, and I spoke on RPR and how coaches can use it.

One of the RPR founders, JL Holdsworth, helped me prepare for the presentation by giving me some gems and great ways to communicate these concepts. One of the best analogies I stole from him is that the nervous system is the electricity of the body. When you walk into a dark room, you don’t immediately go changing the light bulbs or lighting fixtures in order to illuminate it. You flip the light switch. You give the light bulbs a source of electricity.

This is what RPR does. Electricity is the nervous system. Light bulbs are your muscles. Lighting fixtures are the skeletal structures. RPR helps you flip the switch, so then you can determine when or if you even need to mess with the bulb or fixtures.

What I’ve learned while doing RPR on myself and with every single one of our athletes is that our brain is not the biggest fan of bilateral movements.

Video 1. This example illustrates how a bilateral movement can instantly alter stability and movement.

These three a-ha! moments collectively brought it home for me: The journey from thinking I knew it all, to realizing I didn’t really know anything, to learning more, and then to realizing I know maybe a little more now but not that much…and then it continued to experimenting and seeing real-life examples of a concept give incredible results.

We still do plenty of bilateral work, especially for athletes with a younger training age. But for the most part, all of our KPIs are unilateral movements, says @JustinOchoa317. Share on XAs I mentioned earlier, these are the reasons why we turned to a single leg RDL and determined it completely worth our athletes’ time to prioritize in a program. We still do plenty of bilateral work, especially for athletes with a younger training age. But for the most part, all of our KPIs are unilateral movements.

What Makes the SLRDL Special?

So, what is a Romanian deadlift anyway? I like to simplify it to this: An RDL is a loaded hip hinge that does not involve a pull from the floor. You unrack the bar at waist height and begin your rep with the eccentric phase, rather than pulling a bar from the floor.

The RDL, in general, can have a great effect on posterior chain strength, most specifically hamstrings and lower back integrity. Of course, you’ll get a lot of lat engagement as well as glute activity, but most would consider it a hamstring exercise in terms of primary movers.

The RDL is not just a training tool, but a diagnostic tool too. This is helpful for teaching athletes how to hinge at the hips, load the posterior chain, and gain access to these sorts of hip-dominant positions. Not that knee-dominant movements need to be avoided, but there are definitely clear times to use one or the other in a lifting environment.

In general, those are some of the things we see in a classic RDL, but here are three specific reasons why I love the single leg version so much.

1. Grip Is Not a Limiter

Part of the bilateral limb deficit (BLD) theory that doesn’t get talked about enough is how grip-based exercises work into the concept. In an RDL, grip is often a limiting factor. This means athletes will often fail reps due to grip failure before the hamstrings, glutes, and back are even close to their limits.

The beauty of the SLRDL is that it kills two birds with one stone in terms of the BLD. The sum of the unilateral work exceeds the limit of the bilateral work, but also the grip never changes. A barbell SLRDL still allows athletes to use both hands to hold onto the bar, making grip much less of a limitation compared to the bilateral version.

An example of this would be an athlete who can SLRDL 250 pounds but can’t RDL 500 pounds because their grip gives out. Sure, you could make grip training more of a priority in training, but then you’d have to possibly sacrifice training other attributes that are much more important to the athlete’s performance.

2. Movement Assessment

Another benefit of the SLRDL—which I touched on earlier—is its value as a movement assessment. You can learn a lot about an athlete just by watching them performing an SLRDL, including things you would not be able to see in a standard RDL. One example would be an athlete’s pelvic or hip positioning. No one is symmetrical, nor should we expect them to be, but knowing where these asymmetries are and how they alter function is a powerful tool for coaches.

You can learn a lot about an athlete just by watching them performing an SLRDL, including things you would not be able to see in a standard RDL, says @JustinOchoa317. Share on XVideo 2. Hip opening: Shows a common difference you may see in a left-legged versus right-legged SLRDL.

Compensations like this could be due to a range of causes, but at least it gives coaches a start in helping resolve the issue. It could be as simple as uneven hips that a chiropractor could adjust or simply teaching an athlete how to shift into their hip during the movement. On the contrary, it could be more complex, such as a muscular imbalance that forces the athlete into this position. Or it could be some sort of protective mechanism the brain has forced the athlete into to cover up a deeper issue.

Every situation is different, but the diagnostic features of a simple SLRDL allow you to see these things, whereas in a standard RDL they could easily be hidden, since it’s a two-legged exercise.

3. Build Adductor Strength

Lastly, I think my favorite benefit of the SLRDL is the amount of adductor strength you can build up in a very functional way. Most adduction exercises isolate the movement and neglect the collaborative nature of the involvement of the hamstrings and glutes.

I think my favorite benefit of the SLRDL is the amount of adductor strength you can build up in a very functional way, says @JustinOchoa317. Share on XYou’re probably picturing the classic commercial gym seated adduction machine that almost always makes for some fantastically awkward eye contact from across the gym. The adductors (or “groins”) themselves are a cluster that tends to get grouped together under this blanket term, but they also play such a large role in athletic movements that it’s valuable to train them along with those muscles they often work with synergistically.

Using the hinge pattern—which is predominately hamstrings, glutes, and lats working with the adductors—will not only let the athlete strengthen their adductor complex, but it will do so in a way that effectively translates to their sport. In sprinting, for example, those muscles are vital in every stride. In lateral shuffling, those same muscles emphasize the adductors even more to produce force.

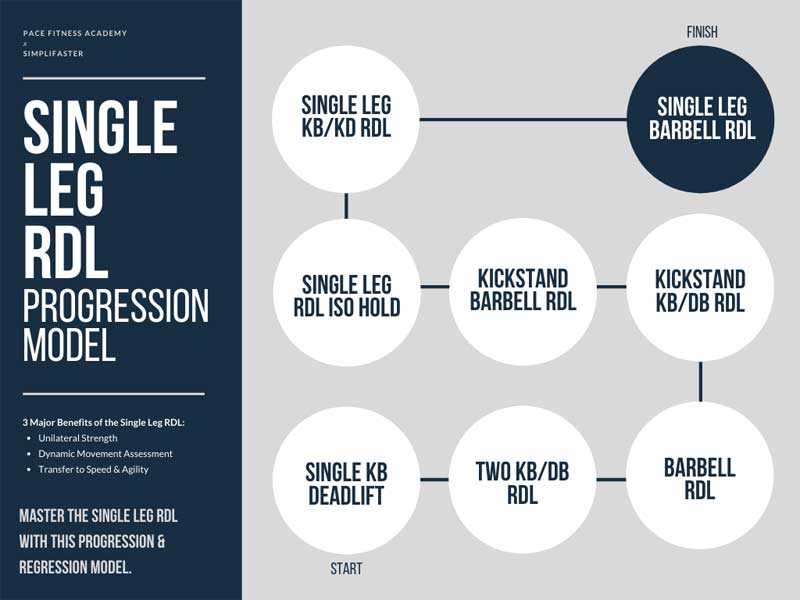

Progression

The single leg RDL is definitely not a beginner’s lift. Although it looks smooth and simple when flawlessly executed, it is a skill that must be learned and refined over many months of training.

A great place to start is with a simple bilateral hip hinge, such as a barbell RDL or a KB deadlift. I believe showcasing sound mechanics in this lift is an important detail for this progression. Even though it’s the furthest lift away from an SLRDL, it still sets a good foundation for figuring out the hinge pattern.

Video 3. This is an example of a reactive neuromuscular training (RNT) barbell RDL, using a band to pull the bar away from the body so the athlete must focus on keeping their lats engaged and their hinge motion smooth.

As we continue to move toward an SLRDL, the bilateral options are still very key. Not just from a movement standpoint, but also from a strength and resilience point of view. If the movement pattern looks great, but we can’t load it much, it may not be the right time to progress forward. When the coach and athlete both feel comfortable and experienced with the bilateral variations, moving to a unique stance called “the kickstand” is a game changer.

A DB or KB loaded kickstand RDL features a staggered stance that allows athletes to emphasize one leg without completely relying on that leg for stability. This is a great bridge from bilateral to unilateral work. You can also progress the kickstand RDL to a barbell to load it up heavier.

Athletes love these kickstand variations. A huge advantage of this stance is that it gives the athlete a little bit more ownership of their lifting positions. I am a big believer that there are certain things coaches DO NOT want to see in a lift, but beyond those obvious major red flags, the rest is very much left to the athlete’s individual preference.

The kickstand RDL gives the athlete more flexibility to find their perfect stance, not the perfect stance. And as long as the standard principles of the RDL remain intact, everyone wins.

The kickstand RDL gives the athlete more flexibility to find THEIR perfect stance, not THE perfect stance, says @JustinOchoa317. Share on XOnce an athlete gets comfortable with the kickstand RDL, you can begin to move into true single leg work with either a dumbbell or kettlebell. You could even introduce single leg RDL isometric holds before moving to loaded variations. I am a huge fan of isometric holds not only for their help with new movements, but also for their huge benefits for tendon health.

Video 4. Tempo single leg RDL with KB or DB.

The end goal is to get to a clean barbell single leg RDL like the one in Video 5. Some athletes may skip certain steps, others may start at different points of the progression model, but this is just an outline of some options we can use to help achieve the end goal.

I should note that I am not as particular as other coaches when it comes to the back leg of an SLRDL. I personally prefer it to have some knee flexion—the bent back leg helps the athlete balance better because keeping that leg in closer to their center of mass helps them stay tight rather than reaching out and away from the body. I am not a fan of the straight, locked-out back leg. Some athletes end up somewhere in between, which is just fine, but we coach it with more bend in the back leg than typically seen.

Video 5. A 165-pound high school junior with a 225-pound barbell SLRDL.

Above all, if the working leg looks and feels good, I’m not going to overly obsess about the non-working leg if the athlete is comfortable. Sometimes, less coaching is more. Again, we want the athlete to find their perfect stance, there is no one-size-fits-all approach.

Here are a handful of my favorite accessory lifts that may also serve as useful lifts in the progression toward a single leg RDL:

- Oscillatory RDL

- Eccentric overload tempo RDL

- Bent over straight arm lat pulldown

- SB hamstring curl (one or two legs)

- Hip airplanes

- SLRDL iso hold

- Copenhagen plank

- Unstable single leg RDL (Video 6)

Video 6. Athlete performs single leg RDL with earthquake bar.

From Performance Indicators to Performance Outcomes

Since putting more emphasis on single leg RDLs, we’ve witnessed a huge increase in our athletes’ single leg strength and jumping ability, which is to be expected. We’ve also seen a drastic improvement in balance and stability, both in the weight room and in sport, without ever doing anything that could be categorized as “balance training.”

Kind of an odd “feat of strength,” we challenge our athletes with is the five-minute single leg balance iso. It’s simple. Take your shoes off and balance on one leg for an unbroken five minutes. Stable and balanced, not hopping around or wobbling the entire time.

This is a great way to train proprioception and really teach athletes how to use their feet to communicate with the ground and the rest of their body. Everything starts with the feet, so we can’t forget to train them like we would any other muscle group. Believe it or not, after about two minutes, this turns into a full-body exercise.

Since putting more emphasis on SLRDLs, we’ve seen a drastic improvement in balance and stability, both in the weight room and in sport, without doing any “balance training,” says @JustinOchoa317. Share on XThe SLRDL and this particular iso hold challenge have helped each other back and forth nicely. Almost every athlete we have who is older than 15 is able to hold this for five minutes. We also have several athletes who can SLRDL their body weight or more for 1-3 reps, which is pretty impressive.

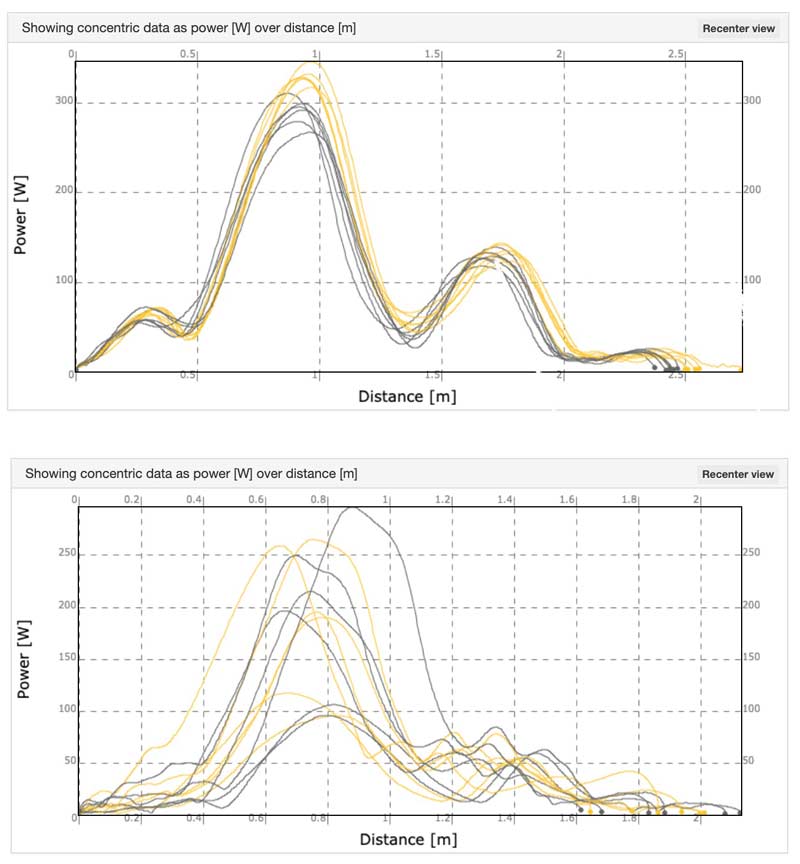

Although we’re relatively new to the 1080 Sprint, we’re also assessing data in sprints and jumps and noticing that our athletes who have been with us for multiple off-seasons (and therefore done a lot of SLRDLs) have much more symmetrical unilateral data in sprints and jumps compared to our newer athletes.

Although I have absolutely nothing against the Olympic lifts, barbell conventional/sumo deadlifts or barbell back squats, these are three extremely common lifts that we rarely utilize in our programming. I would say less than half a percent in the last five years. I have not seen anything that would lead me to believe that those are necessary or more beneficial to a program than some of the alternatives, including the SLRDL.

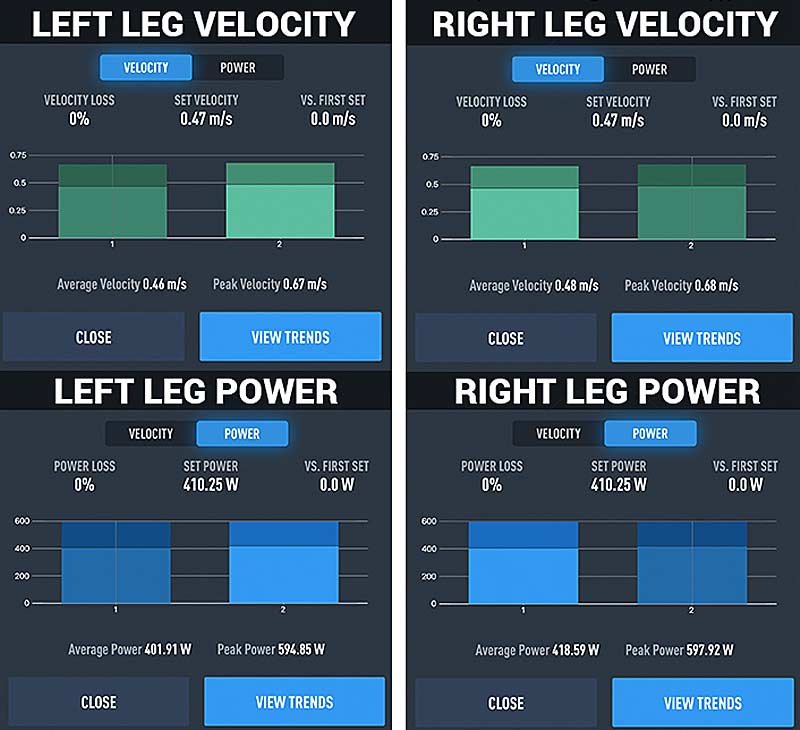

Aside from the 1080 Sprint, we use PUSH for our VBT training systems and also use it for some of our jump training and testing. I really like to see single leg broad jumps and single leg lateral jumps with the PUSH data to look into whether an athlete is favoring either side, and if so, which one. Again, we can’t expect anyone to be perfectly symmetrical, but having high-quality athleticism on either side of the body is essential for performance and health.

Video 7. Single leg lateral jumps performed with PUSH data.

A very drastic example (video 7) is the case of a pro basketball player who was coming off ACL surgery and completely cleared to play. He had finished rehab and was back active on the court. His lateral broad jump speed was .30 m/s apart between his surgically repaired leg and the healthy leg. After a 10-week strength and conditioning block with a heavy focus on unilateral work, he was able to improve his scores as a whole and also bring them within 0.01 m/s of each other.

This athlete was working up to a daily 1RM, testing out heavy singles until he reached an average set velocity of around .35 m/s or an RPE 8/10 (assuming his form looks solid).

Another benefit of having the VBT data is that you can see what movement speed and power look like from week to week, or even within a given amount of sets in a single training session. Of course, nothing is going to replace verbal coaching and feedback from athletes, but having technology point out something awry can lead the coach to inquire deeper and find an issue that may need to be addressed.

Overall, if you are equipped with the facility space and freedom to upgrade the SLRDL to a main lift, it’s well worth it for your athletes.

Since you’re here…

…we have a small favor to ask. More people are reading SimpliFaster than ever, and each week we bring you compelling content from coaches, sport scientists, and physiotherapists who are devoted to building better athletes. Please take a moment to share the articles on social media, engage the authors with questions and comments below, and link to articles when appropriate if you have a blog or participate on forums of related topics. — SF

Thanks for this interesting article. How many reps would you recommend for the SLRDL using a barbell?

Hi, would you say that the SL romanian deadlift could be used as the main lift for 1 REP max eventually?

as going heavier targets your fast twitch fibers better.

Thanks in advance.

“If an athlete can split squat 350 pounds on each leg, an equal stimulus would be a 700-pound two-legged squat” – You have a logical flaw in this argument. You just missed the bodyweight in the equation. With these high numbers it sounds about right but just perform a two-legged squat with 5 pounds and a split squat with 2.5 pounds. Is this two-legged squat equally difficult than this split squat? Obviously not. The single-legged version is way more difficult. You are not only squatting the weight on your back but also your bodyweight (at least partially).

True, but there are studies demonstrating that a *true* one legged squat with bodyweight is approximately the same load as bilateral squatting one’s bodyweight. Doesn’t apply to split squats though, given the distribution of load.