A coach should continually reflect, adapt, and innovate to develop, both as a professional and as an individual.3 Indeed, according to some authors, “it is the capacity of coaches to practice, reflect and then learn from their experience that is central to developing coaching effectiveness.”13

How can we implement reflective practice on a daily, weekly, monthly, or yearly basis? This article provides reflective tools that coaches can easily use in their daily practice along with examples from my work in Canadian university football.

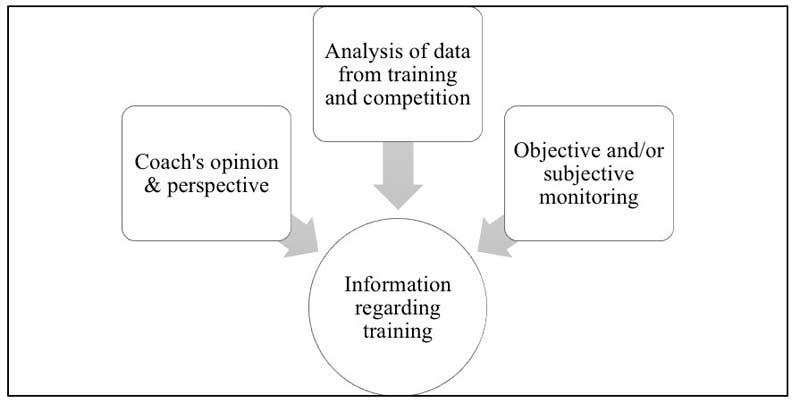

As an interesting starting point, we can combine the different sources of information that represent the constant change associated with sport and use the combined information to support the coach’s decision and training processes.12 Nowadays, data is required not only to evaluate and track improvements in training and competition but also to help coaches make training decisions.

Tools to Implement Reflective Practice

Using statistics, video analysis, and discussions with peers enables the coach to take a step back and evaluate an event.7 Different sports will generate different sets of game-related statistics. For example, in Canadian university football, we had a game-related key performance indicator (KPI) that characterized our defensive play. Per game, we wanted less than three explosive plays or plays where the opponent’s offensive unit completed a play of more than 20 yards. These statistics provided coaches with specific information regarding the game’s tactical aspect.

Reflective Cards

Reflective cards can be part of our data analysis either post-training or post-competition.4,5,10 As part of my Ph.D. thesis, we asked Canadian university football coaches to fill out post-competition reflective cards. The cards contained a few questions related to contextual variables (opponent, score, home or away, weather, etc.), game-performance KPI, and weaknesses they should address in the upcoming week of practice.

We also had coaches fill out reflective cards after each training session during the week, answering prompts such as:

- briefly describe the training session

- evaluate what went well and what went not so well

- explain why they went well and why they did not

- propose improvements for the next training session

Reflective cards, as opposed to a reflective journal, take a few minutes to complete, are straight to the point, and can provide valuable information that coaches can compile and review.

Video and Voice Recording

Time can be a limiting factor, however, when using a written form of reflective practice. Luckily easy access to technology gives us other tools to use such as video. As reported by Kidman,11 videotaping oneself while conducting a training session has gained popularity in coach education settings as a means to self-train. Another interesting method we can pair with video is the Thinking Aloud (TA) method where coaches are asked to verbalize their thoughts while performing a coaching task.

Using a Dictaphone or microphone, for example, they can then put into words their inner speech; encode and vocalize any scents, visual stimuli, or movement; and explain their thoughts, ideas, hypotheses, or motives regarding a specific task. TA shares some principles with Schön’s “reflection-in-action” by allowing “coaches to reflect-on their in-event reflections” when reviewing the recordings19 by themselves or with the help of a coach educator or mentor.

Obtaining Objective and Subjective Data

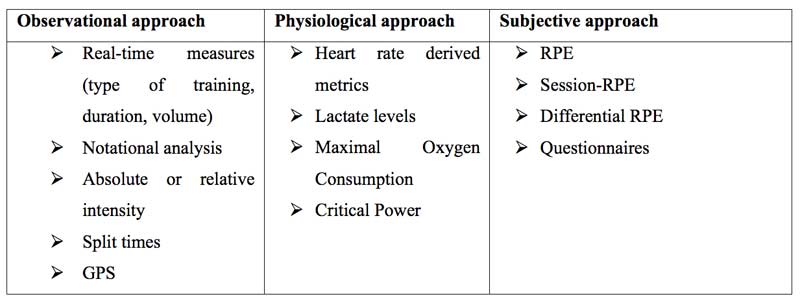

We can obtain objective and subjective data in a variety of ways. To gather information on external training loads (work completed by the athlete and measured independently of their internal characteristics) and internal training loads (the relative physiological and psychological stress imposed on the athlete), we can use three main approaches:18

- the observational approach

- the physiological approach

- the subjective approach

We could also add any neuromuscular assessments to these approaches, such as various jump tests.

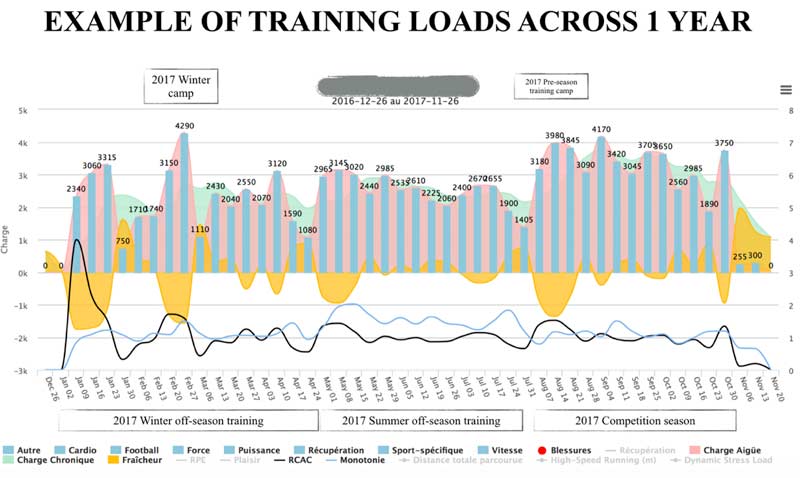

With Canadian university football players, we monitored internal training loads using the Session-RPE method (sRPE = duration of training x RPE) to gather information about training. Looking retrospectively at the data collected over the previous two years, we were able to adjust the training content to match the various demands of the student-athletes better.

For example, in the graph below, we can identify increased acute training load and decreased freshness levels at the beginning of the winter semester, during winter camp, at the beginning of summer training, and during the pre-season. Equipped with this information, the coach can adjust training and implement more recovery methods before or after these periods to facilitate recovery. The coach could also plan for lower training load at specific times in the academic calendar, such as the last two weeks of April when student-athletes have assignments to hand in and exams to prepare for.

Combining objective and subjective data such as training load with wellness questionnaires is a powerful way for coaches to optimize training and prevent overtraining. It also provides good feedback about how players are handling different stressors and sets the dialogue for good communication between the coach and the athletes.

Daily Introspection

Reflective practice requires a certain degree of introspection from the coach and should be a daily activity.15 One could use a reflective journal, reflective cards, video, shared reflections, or an oral approach such as TA to implement a reflective practice.

Writing down one’s actions and thoughts following an event or a day’s work in a journal or logbook quite often serves as an introduction to reflective practice. However, recent studies question this approach,2 especially the time it takes to sit down, pause, and reflect.14 Moreover, the entries in a coach’s reflective journal at first might look more like descriptions of the various events rather than a reflection on those events.

Critical reflection on events improves a coach's decisions and training processes, says @xrperformance. Share on XInstead, coaches can engage in a critical reflection. This requires coaches to not only question their thought-process but also question or review their beliefs and values regarding their experiences as well as the wider social context of their practice.6,8 This “self-induced momentary confusion” can be supported and guided by a coach educator or mentor, who can help motivate one to sustain a reflective practice.

Here’s a very good example of this support system as described by Gallimore.3 A struggling high school basketball coach implemented reflective practice after meeting and communicating over several years with legendary basketball coach John Wooden. The high school coach’s practice and coaching record improved over these years.

In the end, a reflective practice appears to benefit both professional and personal development in various fields, including coaching. Using reflective practice to improve one’s knowledge and coaching qualities, such as communication, also impacts the coach’s athletes. The coach-athlete-performance relationship would likely benefit from taking time to reflect. Fellow coaches are encouraged to triangulate the different sources of training decision-making information that best fits their own coaching context.

References

- Borresen, J., & Lambert, M. I. (2009). The quantification of training load, the training response and the effect on performance. Sports medicine (Auckland, N.Z.), 39(9), 779‑ http://doi.org/10.2165/11317780-000000000-00000.

- Dixon, M., Lee, S., & Ghaye, T. (2013). Reflective practices for better sports coaches and coach education : shifting from a pedagogy of scarcity to abundance in the run-up to Rio 2016. Reflective Practice, 14(5), 585‑ http://doi.org/10.1080/14623943.2013.840573.

- Gallimore, R., Gilbert, W., & Nater, S. (2014). Reflective practice and ongoing learning: a coach’s 10-year journey. Reflective Practice, 15(2), 268‑ https://doi.org/10.1080/14623943.2013.868790.

- Ghaye, T. (2008). Putting reflection at the heart of good practice: The user guide. Reflective Learning-UK.

- Gilbert, W. (2017). Coaching Better Every Season : A Year-Round System for Athlete Development and Program Success. Windsor, Ontario: Human Kinetics.

- Gilbert, W., & Trudel, P. (2013a). The Role of Deliberate Practice in Becoming an Expert Coach : Part 3- Creating Optimal Settings. Olympic Coach Magazine, 24(2), 15‑

- Gilbert, W., & Trudel, P. (2013b). The Role of Deliberate Practice in Becoming an Expert Coach: Part 2 – Reflection. Olympic Coach Magazine, 24(1), 35‑

- Hickson, H. (2011). Critical reflection : reflecting on learning to be reflective. Reflective Practice, 12(6), 829‑ http://doi.org/10.1080/14623943.2011.616687.

- Hopkins, W. G. (1991). Quantification of training in competitive sports. Sports Medicine, 12(3), 161‑

- Hughes, C., Lee, S., & Chesterfield, G. (2009). Innovation in sports coaching: the implementation of reflective cards. Reflective Practice, 10(3), 367‑ http://doi.org/10.1080/14623940903034895.

- 11.Kidman, L. (2005). Athlete-centred coaching: Developing inspired and inspiring people. (T. Tremewan, Éd.). Christchurch, New Zealand: Innovative Print Communications Ltd.

- Kiely, J. (2012). Periodization paradigms in the 21st century: Evidence-led or tradition-driven? International Journal of Sports Physiology and Performance, 7(3), 242‑ https://doi.org/10.1123/ijspp.7.3.242.

- Knowles, Z., Borrie, A., & Telfer, H. (2005). Towards the reflective sports coach : issues of context, education and application. Ergonomics, 48(November), 1711‑ http://doi.org/10.1080/00140130500101288.

- Knowles, Z., Gilbourne, D., Borrie, A., & Nevill, A. (2001). Developing the Reflective Sports Coach : A study exploring the processes of reflective practice within a higher education coaching programme. Reflective Practice, 2(2), 185‑ http://doi.org/10.1080/14623940120071370.

- Lyle, J. (2002). Sports coaching concepts : A framework for coaches’ behaviour. London: Routledge.

- Robson-Ansley, P. J., Gleeson, M., & Ansley, L. (2009). Fatigue management in the preparation of Olympic athletes. Journal of sports sciences, 27(13), 1409‑ http://doi.org/10.1080/02640410802702186.

- Schön, D. A. (1983). The reflexive practioner: How professionals think in action. Basic Books Inc.

- Wallace, L. K., Slattery, K. M., & Coutts, A. J. (2009). The ecological validity and application of the session-RPE method for quantifying training loads in swimming. Journal of strength and conditioning research, 23(1), 33‑ https://doi.org/10.1519/JSC.0b013e3181874512.

- Whitehead, A., Cropley, B., Miles, A., Tabo, H., Quayle, L., & Knowles, Z. (2016). ‘Think Aloud’: Towards a framework to facilitate reflective practice amongst rugby league coaches. International Sport Coaching Journal, 3(3), 269‑

Since you’re here…

…we have a small favor to ask. More people are reading SimpliFaster than ever, and each week we bring you compelling content from coaches, sport scientists, and physiotherapists who are devoted to building better athletes. Please take a moment to share the articles on social media, engage the authors with questions and comments below, and link to articles when appropriate if you have a blog or participate on forums of related topics. — SF