I am about to retire from teaching, which has a way of forcing you to look back on your career—which, for me, has included 35 years of coaching. As I reflect, I have been passionate in my pursuit of developing speed. As I reflect, I also wonder if I have the led the life of Captain Ahab in a self-destructive search for his white whale or that of Arthurian legend Perceval in his quest for the Holy Grail to save Camelot. My quest has taken me down many paths—some destructive, some enlightening.

Regardless of where I was on the journey—which still continues—I’ve always dealt with some form of strength and the kinds of strength that have been defined. We all know and love max strength. We can thank Supertraining and other Cold War-era literature for concepts like Speed Strength and Strength Speed, which really just define how fast a bar is moving in a weight room scenario. We can ask football coaches about Farmer Strength, which I guess is the ability to be explosive throwing things. I think I possess Old Man Strength which is the ability of an old guy to tap into his “muscle memory” and perform a feat of strength that wows younger people (the long-range result is the old guy then needs three visits to the chiropractor, but feels good emotionally that he still “has it”).

While all of those things are real and legitimate, I have always been searching for attributes that someone fast has and slow people don’t have: something I am calling Sprint Strength.

I have always been searching for attributes that someone fast HAS and slow people DON’T HAVE: something I am calling *Sprint Strength*, says @korfist. Share on XOne definition would be how fast you can be strong? Another might be how fast can you apply force into the ground? But it can also mean how does your body react with a large amount of force running through your body? What gets absorbed, what gets reused, what creates displacement of joints, and what turns to heat? That force can be what happens when your foot hits the ground, but it can also mean how it reacts to a limb that constantly stops, accelerates, and decelerates at a high velocity. My lifelong goal has been to find the Holy Grail strength that can turn 11.5 athletes into 10.3 speed demons. My white whale is Sprint Strength.

My Ahab moments would be a chronology of equipment acquisitions, most of which have ended up like the whale carcasses left behind The Pequod. The tools that have helped tremendously have been 1080 Motion equipment—not only in their training applications, but in the data I can mine from applying it. In addition to isolating specific movements that are vital to speed—like plantar flexion torque—I can also put higher amounts of force into a movement to see how the body will react. An example might include a leg getting pulled into flexion and the body responds with spinal flexion, either to lower the center of mass to not fall or use the spine to dissipate forces. Both initial reactions are neural in that safety and balance precede performance in every movement. Or, in more of a subjective assessment, athletes can feel other muscles jumping to help absorb the force, creating a muscular compensation pattern.

Fatigue can have the same impact. When performing an exercise forcing plantar flexion torque, after a few reps athletes with weak plantar flexion will note that they feel their hamstring start to fatigue. That is an indication that their plantar flexors lack endurance or strength to keep the movement going. Since the athlete has a rep target, their body resigns to help reach the target (more on plantar flexion later).

With access to weight room numbers, 1080 Sprint data, 1080 Synchro data, and video, I have started compiling various numbers and exercises that have carryover to sprinting fast. I think what surprised me the most was that it wasn’t about the highest maxes and big weight room numbers, but it was about thresholds—or, just the concept of being strong enough to go past the threshold or “speed barrier.” And once over that barrier, it will be enough to set up the next step. Speed is like a perfect story: one good step sets up another, until it doesn’t. And then we see how the body will solve the problem. So “call me Ishmael” and let’s see how this story unfolds.

Speed is like a perfect story: one good step sets up another, until it doesn’t. And then we see how the body will solve the problem, says @korfist. Share on XAhab Meets Inception: The Swing Leg

The story I have to tell here is not something I’m going to lay out in a chronological narrative. I want to be trendy and jump around to different moments of a sprint, ranging from a period of time in the cycle of the leg, to a different distance on the track, or even variables such as not running straight but curved. I promise I am not trying to be a fancy Christopher Nolan/ Quentin Tarantino type of writer—I am just collecting my thoughts as I prepare for my track season. To start this series, I want to look at the most important, undertrained aspect of running: the swing leg.

Research in the last 10 years has changed how we see sprinting. As we move further away from the 1980’s research that said the stronger the athlete, the faster the athlete, we start to look at other factors…because the strongest guy isn’t always the fastest. But since we have focused so much on strength, or Ground Reaction Force, we have forgotten the other vital aspect to all phases of a sprint… limb velocity.

Ken Clark’s multiple research papers on limb velocity were the first times I came across it mentioned in research. When I started my deep dive, I discovered Chinese researchers have recognized the importance of limb velocity as far back as 2014, with Y. Sun’s paper “How Joint Torques Affect Hamstring Injury Risk in Sprinting Swing-Stance Transition” followed by Y. Zhong’s paper “Joint Torque and Mechanical Power of Lower Extremity and Its Relevance to Hamstring Strain During Sprint Running.” The latter paper emphasizes an equation that makes the most sense to me in determining speed.

NET= MUS+GRA+EXF+MDT

- NET is the sum torque acting on a joint. Torque is what gives an athlete the power to pull their body forward 60 degrees from touchdown.

- MUS is power generated by muscle contractions.

- GRA is gravitational forces acting at the center of mass.

- EXF is generated at joints by GRF acting on the foot.

- MDT is the mechanical interactions occurring between limb segments and is the sum of all interaction torques produced by segment movements, such as the angular velocity and angular acceleration of segments.

Muscle power is agonist and antagonist muscles, multiplied by the angular velocity of the joint.

Both of these equations make more sense to me to determine running speed. We have relied on just vertical force for too long—mainly because it’s something we can measure in the weight room. These equations, instead, account for the athlete who can’t squat twice his body weight but can still run. They can also account for the athlete who can squat the house but can’t run. Maybe his limbs have become too heavy to move fast enough to run fast? Or their body weight has surpassed the threshold of what of what it can absorb and hold up? We can use this formula to describe a variety of athletes.

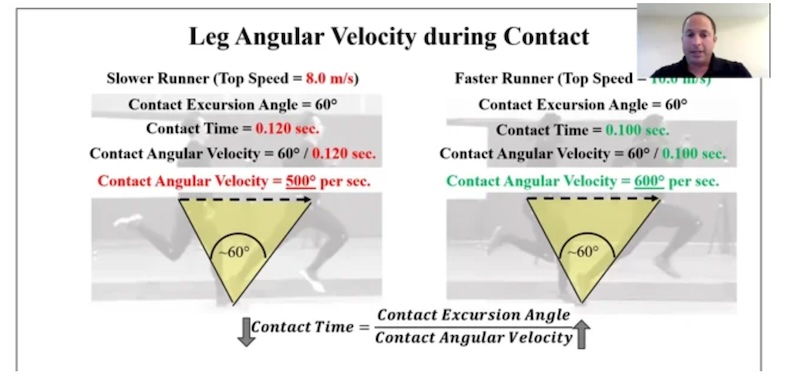

But in this article, we are looking at limb speed. Ken Clark showed in a brilliant YouTube and research paper that when our foot hits the ground, it has to pull our mass over a 60-degree range of motion. To pull your body over that range as quickly as possible, your hip has to create torque. Torque is a rotational element. Think of your body as a socket. Your foot is the actual socket and your leg is the lever that pulls it forward. The socket can go 360 degrees around—but we are stuck in a 60-degree range. We can create more torque by having a longer lever, which we can do to some extent by having a straighter leg on contact or by pushing the lever faster. In a real sense, that would mean bringing the leg faster down to the ground.

How do we train this?

A simple exercise is just a leg swing, but not like the one I see most teams warming up with. Our hip has to rotate or swing 60 degrees. When I see athletes swinging their leg, their torso rotates back and forth, so the range of motion is about half. I have my athletes support their torso by putting their hands on something fixed and focus on not moving their torso. And instead of swing for fun, have them swing with the intent of going as fast as possible. Because the power really comes in the reversal of the leg.

Video 1. Leg Swings.

But swinging a straight leg is not what happens when we run. Upon toe-off, we fold our lever (bend our knee) to reduce the drag (slow down) on our angular velocity (swing leg speed). We can train that too. Toe-off is the moment the foot comes off the ground at the end of the 60-degree range. Some of the speed of the toe-off comes from the energy created by the tension of the foot on the ground. More will come from a clean toe-off, meaning the ability of the foot to finish its rotation with the heel moving forward, not off to the side (see below).

From there, quite a bit of hip flexor activity brings the leg through. It starts with the iliopsoas complex and rectus femoris then takes over, reaching peak force when the swing leg knee is slightly in front of the stance leg. From that point, limb speed has to be reduced by 78% to prepare for the reversal of the limb, asking all the hamstrings to put on the breaks. This is why we try to find eccentric hamstring exercises to prevent strains, which occur at this point of the sprint cycle.

This concept may explain why high knee drills may not be helping your athlete get faster: the peak power, force, and velocity is at midpoint of the swing leg knee passing the stance knee. High knee, hip flexor drills accelerate vertically in an area where the limb is decelerating and reversing course in a sprint gait cycle.

Gaku Kakehata of the University of Tokyo has three great papers looking at this part of the running cycle. He creates two points in the gait cycle: a switch and a scissor.

- A switch has a Part A and a Part B. Part A would be the high knee action and Part B would be the toe-off to knees passing each other.

- A scissor is the relationship between the two legs.

Research showed that the Switch B is correlated with stride frequency. So, what can we do to get that leg to pull the toe off the ground and pull the thigh through faster? We can tap into reflexes. A stumble reflex is what prevents us from tripping. If the brain senses the foot is stuck, it will fire extra hard to get the foot down in time to prevent a trip or fall. We can access this quality in a couple ways. Simply, we can tap our foot into the ground and bring the knee forward as quickly as possible.

A stumble reflex is what prevents us from tripping. If the brain senses the foot is stuck, it will fire extra hard to get the foot down in time to prevent a trip or fall. We can access this quality in a couple ways, says @korfist. Share on X

Video 2. Tap and Go.

Or, we can take inspiration from Ayako Higashihara’s paper “Differences in the Recruitment Properties of the cortispinal pathway between the biceps femoris and rectus femoris muscles”—his research shows how the rectus femoris can “produce rapid increase in motor units” (or, have to turn on a lot faster to prevent a trip of fall). So, we need something to turn everything on faster. This coincides with Kakehata’s work showing that the faster the rec fem fires, the better the scenario for a good scissors and switch. Again, we can tap into a stumble reflex by putting our foot in an ankle cuff attached to a weight stack and let your leg go back 20 degrees. Give a little pull forward to create momentum in the stack, and let it drop for a moment to give the feeling of a trip, and then pull forward hard. In fancy terms, it is an oscillatory isometric for hip flexors.

Video 3. Slack and go.

Looking at how one limb functions by itself would be intralimb dynamics; or, in Kakehara’s paper, the rec fem and bicep femoris contract and reflex inside one limb. Looking at the relationship between the two limbs would be interlimb dynamics, or a scissor. Interlimb dynamics are what is required for us to move forward, but rarely developed or focused on in the weight room.

It starts with contact on the ground with one leg. If the contact is fast enough, it will help pull the hip of the swing leg forward 10 degrees. With the plant leg fixed on the ground, it forces the other half of the gluteus medius to do its other job, which is to rotate the hip forward once the knee is under the hip.

A simple way to understand this concept is to grab something heavy and try to do a biceps curl. If the weight is too heavy, it won’t move—but that won’t stop the contraction. The biceps will continue to fire, which is why your shoulder will roll forward. This concept would coincide with Marcus Pandy’s paper “How muscles maximize performance in accelerated sprinting” where the gluteus medius has an important role in acceleration. One end of the limb is locked on the ground, and as a result the other hip will rotate forward.

How can we train this? I like to do cable pulls with a cuff around the ankle. Usually, people will grab something to keep balance. It is an intralimb exercise because the hand supporting the body provides stability. If I take the hand off the support, now my opposite thigh has to support the hips to pull the leg through and it becomes an interlimb exercise. I like to add a step to excite my cross-crawl reflex.

Video 4. Step and go.

To add the hip rotation, I would do the same exercise, but block the opposite hip and allow the swing leg hip to rotate 10 degrees forward and back, forcing the plant leg glute med to do the work. There is some good research to show that the rotation of the hips is actually what improves our stride length.

To make it more interlimb, I would eliminate the block and use a step. I can attach my ankle or my thigh: ankle would be more rec fem and thigh would be more glute med. Regardless of my attachment point, I would want to step up to a box so I have an end target to really focus on my hip rotation.

Video 5. Hip Box

In terms of logistics for these exercises, I like a couple weeks of high force for 4-5 reps at a 3-5 sec contraction. 2-3 sets should be plenty. That’s followed by 2-3 weeks of some power movements for higher reps. A medium rubber band is an easy choice with the peak resistance at a point where the attached knee is passing the stance knee. I finish with really fast movements for reps of 20-30.

Since you’re here…

…we have a small favor to ask. More people are reading SimpliFaster than ever, and each week we bring you compelling content from coaches, sport scientists, and physiotherapists who are devoted to building better athletes. Please take a moment to share the articles on social media, engage the authors with questions and comments below, and link to articles when appropriate if you have a blog or participate on forums of related topics. — SF

Hi Chris, very interesting, detailed article. Thank you!!

Very interesting that most S&C coaches want the biggest squat when there athletes ankles aren’t robust enough to handle the violent nature of athletics. Great post and plently of information to pick out of from here which I thank you.