Speed, strength, power, and performance—these facets of sports are the foundation and root of athletic development. As a strength and conditioning coach, my goal is not only to make our athletes bigger, faster, and stronger, but to also make them better movers in time and space.

With many of the high school athletes I work with—predominantly football players—a common trend I see in sprint mechanics is the inability to reach triple extension during the acceleration phase. In order to become better movers, athletes need to learn and understand their own bodies: how what feels good and what does not will respond with their bodies. This concept was further emphasized in a podcast with a coach I respect, Cam Davidson (Director of Performance Enhancement at Penn State). He and Mark Watts from EliteFTS were discussing how Davidson’s approach to training athletes is based off making the athlete “feel” everything, such as feeling that weight at the bottom of a 3-second pause squat or feeling the eccentric load on a bench press.

In some capacity, we all coach our athletes to have a feel for the game. I believe we can apply that same concept in weightlifting that Davidson demonstrates in his training methodology.

In some capacity, we all coach our athletes to have a *feel for the game.* I believe we can apply that same concept in weightlifting, says @debadJuJu. Share on XTransfer to Performance

Whether jumping repeatedly for a rebound in basketball or taking that penultimate step into a spike in volleyball, athletes across different sports need to be explosive. The question becomes: what is the most effective way to train explosiveness in the weight room? The answer must keep in mind that what we do in the weight room also needs to translate to the athlete’s specific sport.

For high school athletes, many coaches use sprints, jumps, and throws to build explosiveness. While jumping, sprinting and throwing are all vital movements, I would argue that—done correctly—Olympic lifts can also play an effective role in improving a high school athlete’s peak force, rate of force production, and explosiveness.

Most young athletes do not begin Olympic Lifting until college, but the benefits are incomparable. At West Point, Coach Tim Caron (also co-founder of Allegiate Gym in Redondo Beach, CA) was my first collegiate Head Strength Coach. Coach Caron’s summer manual for incoming athletes at West Point included basic Olympic lifting movements, such as snatch pulls and block cleans. In 2013, the first time I saw Coach Caron’s manual, I told myself if you want to be great, you need to hone these skills.

In line with that affirmation, many of us on the Army football team who were great lifters also understood how to translate that power to the field. We had players snatch 250+ and clean 300+ with great form and technique, and I eventually became one of them. Coach Caron’s ability to create a self-correcting environment every time we hit the platform bred a team culture where we all continued to refine our lifting technique, which in turn made me a better Olympic lifter.

Relative to sport, Olympic lifting has the ability to train bracing ability and force development, while at the same time promoting neurological adaptations and creating novelty in programming, says @debadJuJu. Share on XRelative to sport, Olympic lifting has the ability to train bracing ability and force development, while at the same time promoting neurological adaptations and creating novelty in programming. All of these are avenues worth pursuing in developing high school athletes.

Bracing Ability

Bracing is one of the most important skills to hone in athletics. Knowing when to brace and when to relax through a lift or in sprint builds coordination within the body. Diaphragmic breathing is key when learning how to brace. The ability to fill the diaphragm and create tension within the body will stabilize it when handling heavy loads.

On the set up of a clean, for example, an athlete creates tension on the bar by filling their belly with air. Performing a clean requires the athlete to:

- Move from a tight position

- Gradually increase speed on the bar

- Explode and catch the bar in a front rack position

From the floor to the moment before the athlete performs the clean, the athlete is constantly tight while keeping tension within their body and contracting their muscles. The moment the athlete cleans, their body cannot be completely rigid and in a contracted state on the catch because the athlete:

- Will not have enough relaxation to catch the weight with heavier loads

- Will lose bar whip on preparation for the jerk

This is where, at the split-second the clean occurs, the athlete has to allow the body to relax in order to allow the body to give on the catch in the front squat position and then contract again when performing the front squat. The catch portion of the clean is where bracing development occurs, because the body has to be in a strong position to receive the weight of the barbell. The timing of the back and forth between contraction and relaxation during the clean makes those neurological connections of when to brace and when to relax.

The ability to rapidly undergo extension and flexion will allow athletes to improve their agility (which can be defined as the ability to accelerate and decelerate constantly). Athletes in cutting sports, such as football and basketball, often need to run to a spot at full speed and decelerate quickly to then move to the next spot. The same concept can be applied in a clean and a snatch. The transition from accelerating the bar from the floor to decelerating the bar on the catch, to then accelerating the bar on a jerk demands coordination from the brain to the body and the muscles needed to complete the lift. This coordination also emphasizes where exercises performed in the weight room translate to their actual athletic performance.

Force Development

Force is a factor in every sport, such as the amount of force an athlete can produce to hit another player on a football field or how much force they can produce to smack a baseball out of the park. One of the seven power development factors is rate of force development (RFD), which, according to Owen Walker, is a measure of explosive strength and how fast an athlete can produce force.

The ability to create force under load at rapid speeds allows for the athlete to improve the other abilities needed in their sport, says @debadJuJu. Share on XThe ability to create force under load at rapid speeds allows for the athlete to improve the other abilities needed in their sport. Most well-trained athletes that incorporate Olympic lifting into their programming yield better results on their jumps, sprints, and throws. Olympic lifting tends to create more explosive force in comparison to other bilateral lifts, such as a back squat or a deadlift due to the ballistic speed on the bar.

Now, as strength and conditioning coaches, we all know that building the perfect athlete is near impossible. It is our role to evaluate our athletes and then strengthen their strengths and correct their weaknesses so that they have the abilities needed to perform at a high level.

As an example of this process, I am going to use one of my athletes and some of the factors I considered to determine whether or not he was ready to learn how to snatch. Aidan is a 5’11”, 170 pound, 16-year-old soccer player at Don Bosco Prep. One of the first steps for his evaluation to see if he’s ready to snatch or clean is based off the same evaluation test USA Weightlifting uses, which is the ability to:

- Front Squat

- Overhead Squat

- Snatch Deadlift

- Overhead Press

When I first started training the athlete, he had little to no thoracic mobility in his upper back, which I knew would be an issue. Aiden did, however, naturally understand a skill that I believe is one of the most difficult patterns to teach a high school athlete: how to hinge. Hinging in the snatch is key to ensure not only explosiveness throughout the lift, but safety from injury. At first, I was not inclined to train him in Olympic lifting, but after doing specific work and corrective exercises to free his upper back, I slowly began teaching him how to snatch.

After an 8-week progression of snatching (along with other compound lifts), Aidan was able to comfortably power snatch 95 pounds without failure. That he can snatch is an accomplishment in itself, but more importantly, his sport coaches have noticed an increase in his burst and explosion during sprints. His ability to put force in the ground has directly translated from the platform to the soccer field.

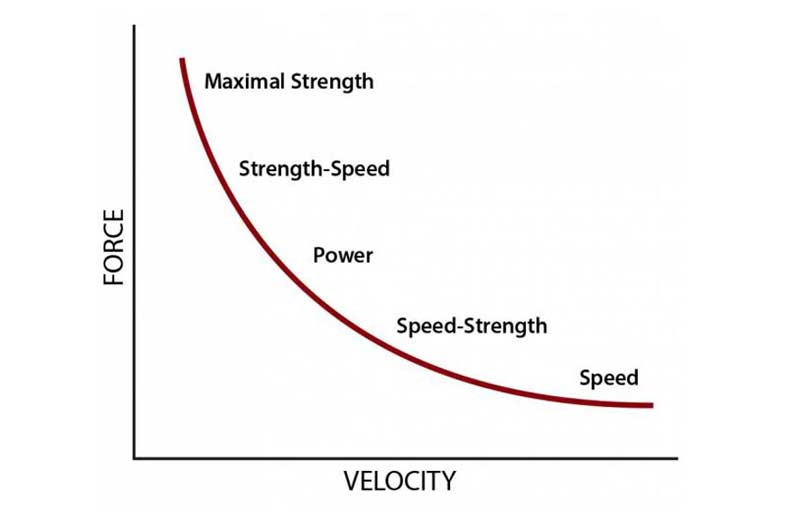

The force-velocity curve is a physical representation of the inverse relationship between force and velocity, and how both factors intertwine. When evaluating Olympic lifting and programming for high school athletes, the goal is to complement their movements with the exercise done in the weight room. For an outside linebacker in football, my mindset would be to program upwards on the strength-speed spectrum, whereas for a triple jumper I would program more with speed-strength in mind.

Neurological Adaptations Through Timing

As I briefly mentioned earlier, the timing and technique portion of Olympic lifting requires a cognitive connection from the brain to the applied muscle groups. According to Joel Smith, the qualities of a fast athlete are to be strong, elastic, coordinated, twitchy, extensible, and fast-twitch dominant.

To build upon this, Olympic lifting allows for the development of powerful rhythm, which correlates to acceleration or jumping. In order to build the rhythm necessary to jump, sprint, or lift, athletes need to make the neurological connections within their body to allow for optimal performance. The ability to escalate force is critical in performing smooth, coordinated lifting movements. The timing built into performing a clean builds upon the aspect of developing the brain from the first pull, to the second pull, to the catch.

The timing built into performing a clean builds upon the aspect of developing the brain from the first pull, to the second pull, to the catch, says @debadJuJu. Share on XOne of my football athletes, Leo, began cleaning prior to when I started training him. The biggest issue Leo had was exploding from the hips and into the catch. Because his hip contact was too low, the bar would move away from him and he was not able to perform heavier cleans. To correct his timing issues, I had to go back to refine his technique by performing high hang clean pulls. By emphasizing the pulls, I was able to ingrain in Leo’s mind when to make contact with the bar to properly perform a clean. Once again, my goal is to translate weight room qualities to the field. Leo’s ability to refine his timing on a clean has helped him be more explosive as a defensive lineman, allowing him to explode through the hips and drive more force into the ground for a more powerful push versus his opponents.

What is the Point?

A lot of science, technical terms, and concepts have been thrown at you, and perhaps you are asking yourself what’s the point? Most high school athletes have never seen the inside of a weight room prior to their freshman year. They are at a very young training age, and to me, that is an amazing opportunity to develop good training habits to build upon.

I want to reiterate, I am not saying that Olympic lifting is the end all, be all and I truly believe in jumping, sprinting, and throwing. However, my case is that adding Olympic lifts into the training programs for high school athletes will improve their sports performance on the field.

Furthermore, I believe that exposure creates experience and to not shy away from the inevitable. Most high school athletes that move to the next level in their sport will, more likely than not, have to Olympic lift. Why not coach and train those movements and patterns at a young training age over the course of four years in high school to provide the best movements in our athletes? As coaches, we need to stop using the excuse that “it’s too time consuming” and “it’s too technical to teach” as pivotal points for not coaching Olympic lifts. We are strength and conditioning coaches, in this field by choice, and if there is a consideration to improve our athletes at the high school level, then we need to exercise that autonomy and use our knowledge to complement their programming by adding Olympic lifts.

Teaching a young athlete how to clean or snatch demonstrates your ability as a strength and conditioning coach to actually coach rather than be a drill coach and put your athletes through cone drills.

Final Thoughts

High school sports are arguably the best time in an athlete’s career to build proper habits. It makes sense to me as a coach to provide my athletes with the tools needed so that they are capable of being better movers on the field. I want to provide the athletes I coach with programs that build upon the basic levels of movement for their given sport, whether that is sprinting a 100m dash or breaking a cut for a touchdown. Athletes that incorporate a new stimulus and variety of lifting (Olympic lifting) will be able to build their athletic base to propel them for better performance in their jumps, sprints, and throws, which in turn will increase their overall performance.

Since you’re here…

…we have a small favor to ask. More people are reading SimpliFaster than ever, and each week we bring you compelling content from coaches, sport scientists, and physiotherapists who are devoted to building better athletes. Please take a moment to share the articles on social media, engage the authors with questions and comments below, and link to articles when appropriate if you have a blog or participate on forums of related topics. — SF

References

Ratelle, Will. “A Case for Training Olympic Lifts in College Athletics.” SimpliFaster.

Walker, Owen. “Olympic Weightlifting.” Science For Sport.

Smith, Joel. Speed Strength.

Larsen, Amber. “The Neurological Benefits of Clean and Snatch Complexes.” Breaking Muscle.