The NFL Combine is the most notable combine for professional athletes when compared to the NBA, MLB, and NHL. As soon as the Super Bowl concludes in mid-February, this is the event all football fans look forward to. For the players participating, the NFL Combine is a weeklong experience filled with meetings, interviews, medical evaluations, and on-the-field drills and performance testing. The performance testing includes the 5-10-5 and three-cone drills to assess change of direction, the broad and vertical jumps to evaluate lower body power, the 225 bench press test for upper body strength/strength endurance, and everyone’s favorite: the 40-yard dash to measure speed.

We will dive into what the training is like in this process at Bommarito Performance Systems (BPS)—one of the premier training facilities for this process, led by Pete Bommarito. This past year was my fourth year assisting Pete with NFL Combine prep. I will look more specifically at one unidentified wide receiver (athlete E) who trained with us during this process and his results at the Combine.

I chose this athlete because he did a great job recording his weight on every set and rep in the weight room, never had any significant injuries that altered his training, and participated in the three major performance tests I wanted to discuss. (More performance tests take place at the Combine, but the six major ones I mentioned earlier are more popular and shared with the fans.)

Where It Begins

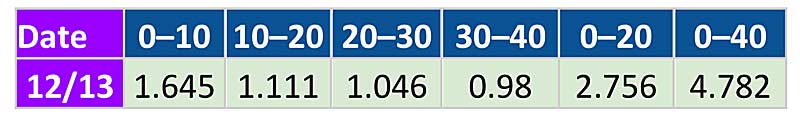

When athletes first show up to start training with us for the Combine, they are evaluated by the medical staff to ensure they are healthy and cleared for training. Athlete E was, so we tested him on all Combine performance tests.

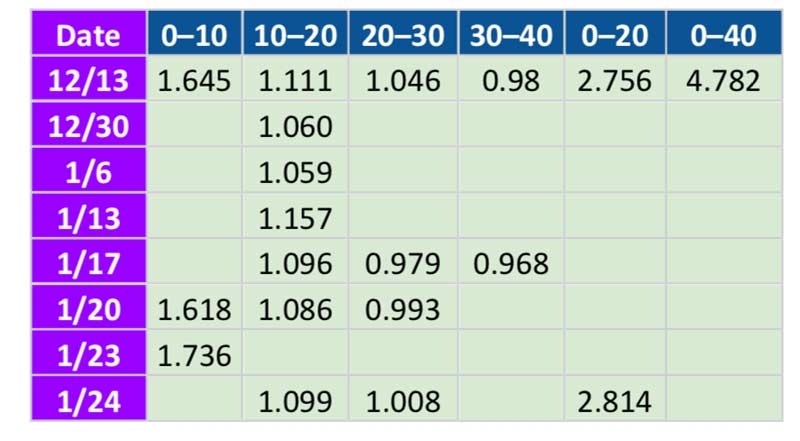

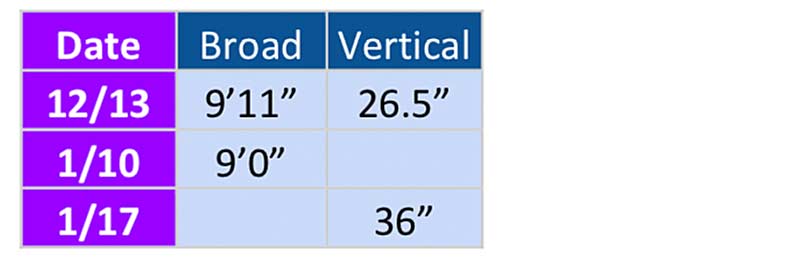

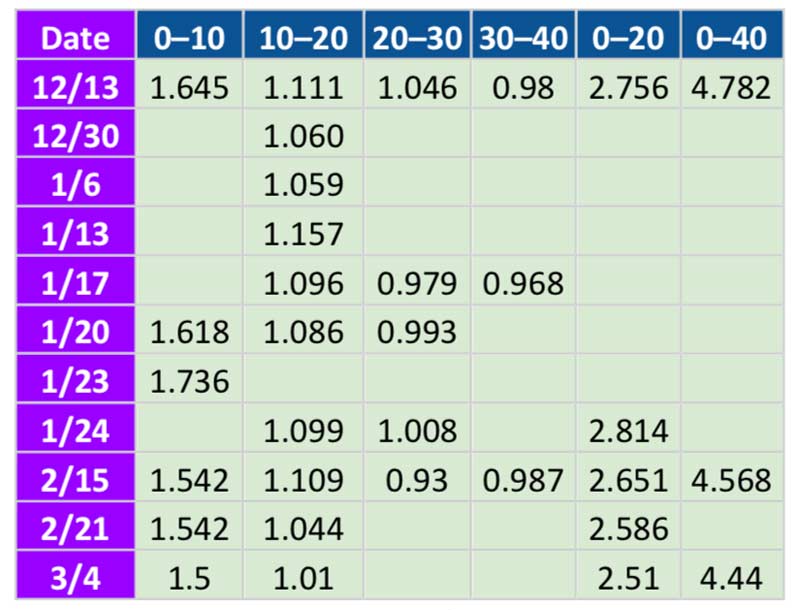

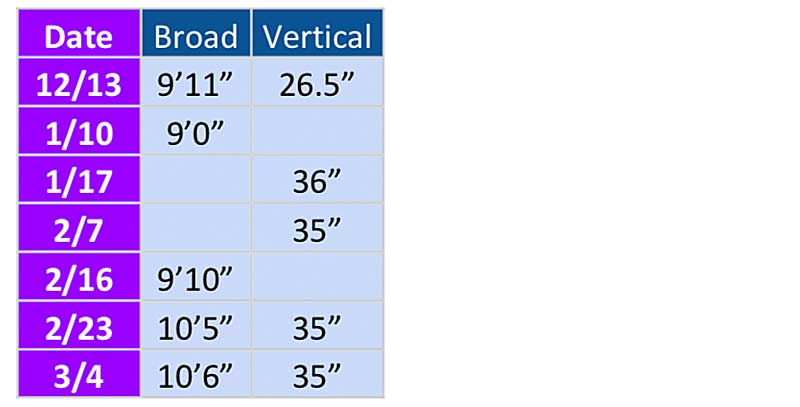

The pre-testing results can humble a lot of athletes: not everyone runs a 4.4 or jumps 32 inches as they think they will, especially after a football season, said @steve20haggerty. Share on XBefore looking at his pre-testing numbers, remember that he just finished a college football season in a Power 5 conference. He was not training for the 40-yard dash and vertical jump; he was playing the extremely physical sport of football. The pre-testing results can humble a lot of athletes: not everyone runs a 4.4 or jumps 32 inches as they think they will, especially after a football season. For playing wide receiver in the NFL at his size (6’3” and 235 pounds), we knew he needed to run in the 4.5 range and jump at least 10 feet in the broad jump and 32 inches in the vertical.

We will look into the training for the 40-yard dash, vertical jump, and broad jump. Athlete E trained speed two days a week and for the agility drills and position work two days per week. A typical schedule for athlete E on a speed day was:

- 6:30 a.m. – Arrive for breakfast

- 7–8 a.m. – Physical therapy, acupuncture, chiropractor, massage, etc.

- 8:15 a.m. – Speed session

- 10 a.m. – Boots or massage

- 11 a.m. – Lunch

- 12:30 p.m. – Film review

- 1:15 p.m. – Lower-body lift

- Ice bath

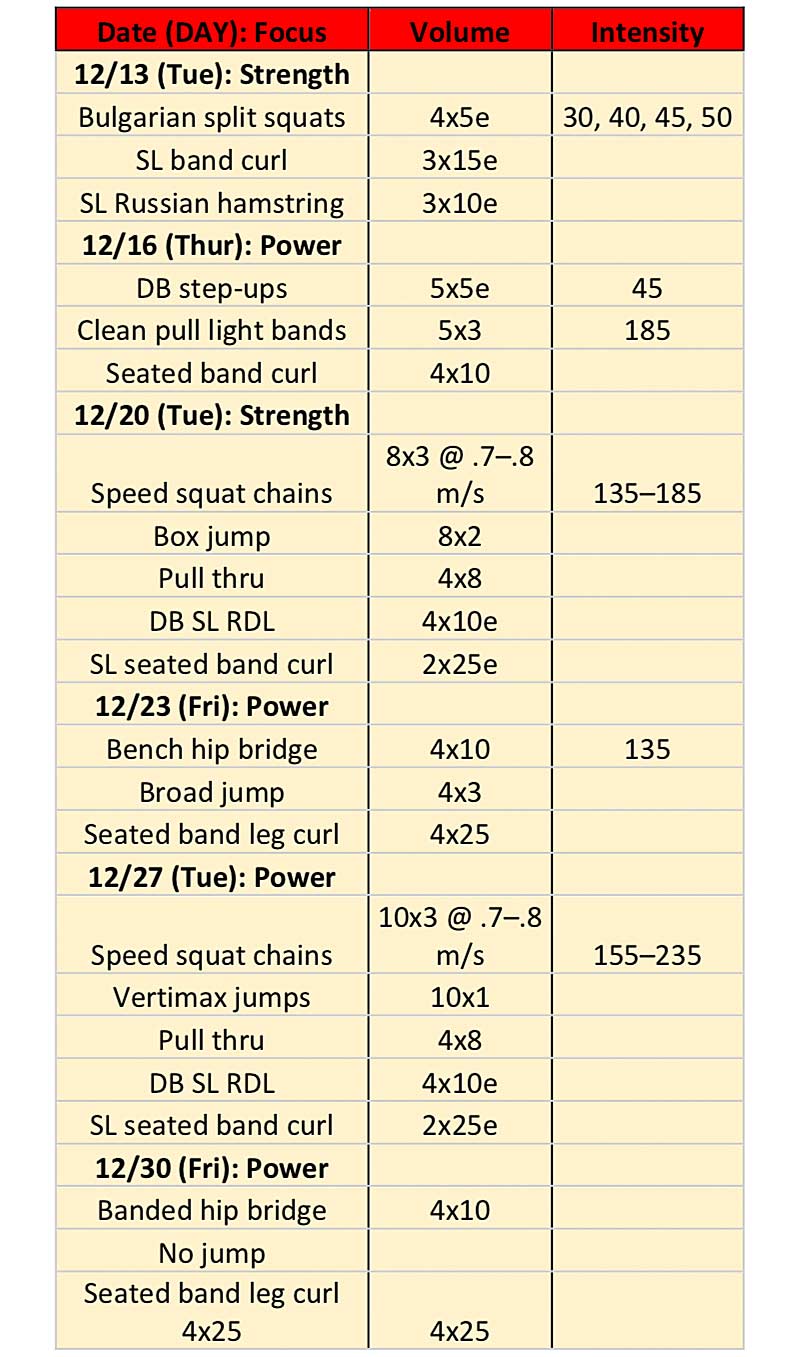

He arrived at the facility in mid-December. For athletes like E, Bommarito Performance serves as a second home, where they will eat, train, and sometimes sleep (naps) for the next two and a half months. Athlete E arrived two weeks earlier than most other players, giving him a head start on learning some of the movements and getting healthy from his football season.

His main focus in December was to get healthy and start building strength and power in the weight room. In the tables below, I include the workout date, the main movement or superset, and the hamstring accessory exercises. There were, of course, other exercises in the workout, but I only included the hamstring-dominant accessory movements. I also included each exercise’s volume and intensity (load, distance, height, etc.).

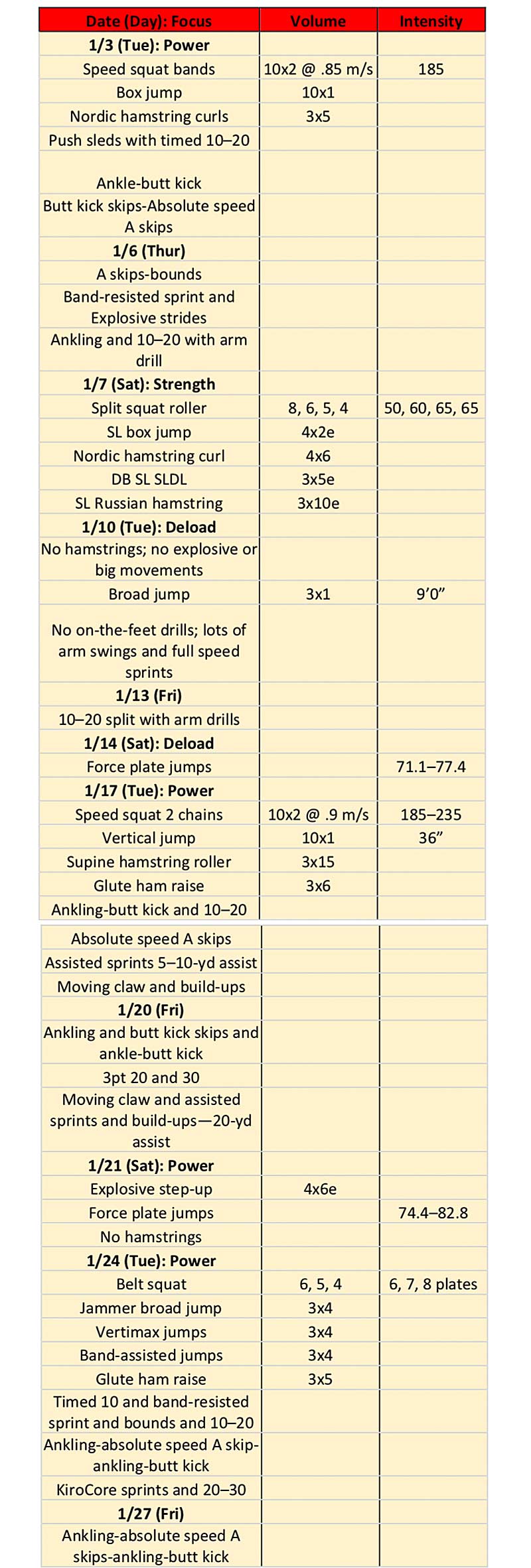

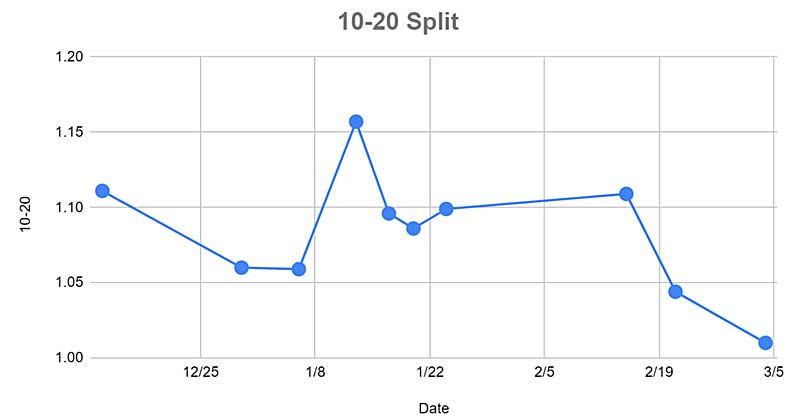

January Training

Once we got into January, athlete E was in a very good position health-wise—he already had had no major injuries, but now he was more or less completely recovered from the football season. Our focus in the weight room shifted more to explosive power. The speed training sessions consisted of more drills to build an overall training volume and capacity. We timed sprints six days in January; in three of them, we only sprinted up to 20 yards. The longer the sprint, the more stress put on the hamstring—which is the No. 1 injury everyone is worried about during this process.

Again, this is a football player, not a track sprinter, so we typically are cautious with sprinting distance until later in the process. Athlete E was also invited to the Senior Bowl, so in the last few days of January, we really pulled back on his training volume just to ensure he felt fresh and recovered for the week of practices ahead.

Again, this is a football player, not a track sprinter, so we typically are cautious with sprinting distance until later in the process, said @steve20haggerty. Share on XAs you will see in both the speed workouts and the weight room lifts, athlete E utilized supersets or complexes in his training (many refer to this as post-activation potentiation). For example, a common approach in the weight room is to speed squat with accommodating resistance and then jump—whether on a box, using a Vertimax, or with something measurable like a Vertec. Our goal was to raise the muscle’s capacity to produce force and the nervous system’s ability to produce force quickly and then apply it in the fashion in which he would be tested, like a vertical jump.

In January, we utilized more weighted movements like squats and a higher volume of them. As we progress, the movements we utilize change to lighter/faster movements and lower volume. On the field for speed training, he would utilize a drill that we would program to improve the technical components of his sprint, then hit a timed sprint.

Athlete E is a strong and muscular athlete. We knew we needed to maximize the start (or first 10 yards) of his run and get his upper body to relax during the last 20 yards of the run. For this, we worked a lot on his starting stance, projecting out, and being very aggressive in his start. We utilized basic kneeling arm swing drills to teach him how to swing fast while keeping his hands, shoulders, and neck relaxed.

I always want to see if we can enhance sprinting mechanics with a drill and then get it to carry over to a full-speed sprint. In early January, we started with slower acceleration-based movements such as sled sprints. As February approached, athlete E spent more time doing max velocity-based drills, like overspeed bounds and sprints.

After doing a heavy sled push sprint, athlete E and everyone in the world will run slower on a timed sprint. That’s okay. Did we get the improved technical components to carry over to the sprint? That’s what we’re looking for.

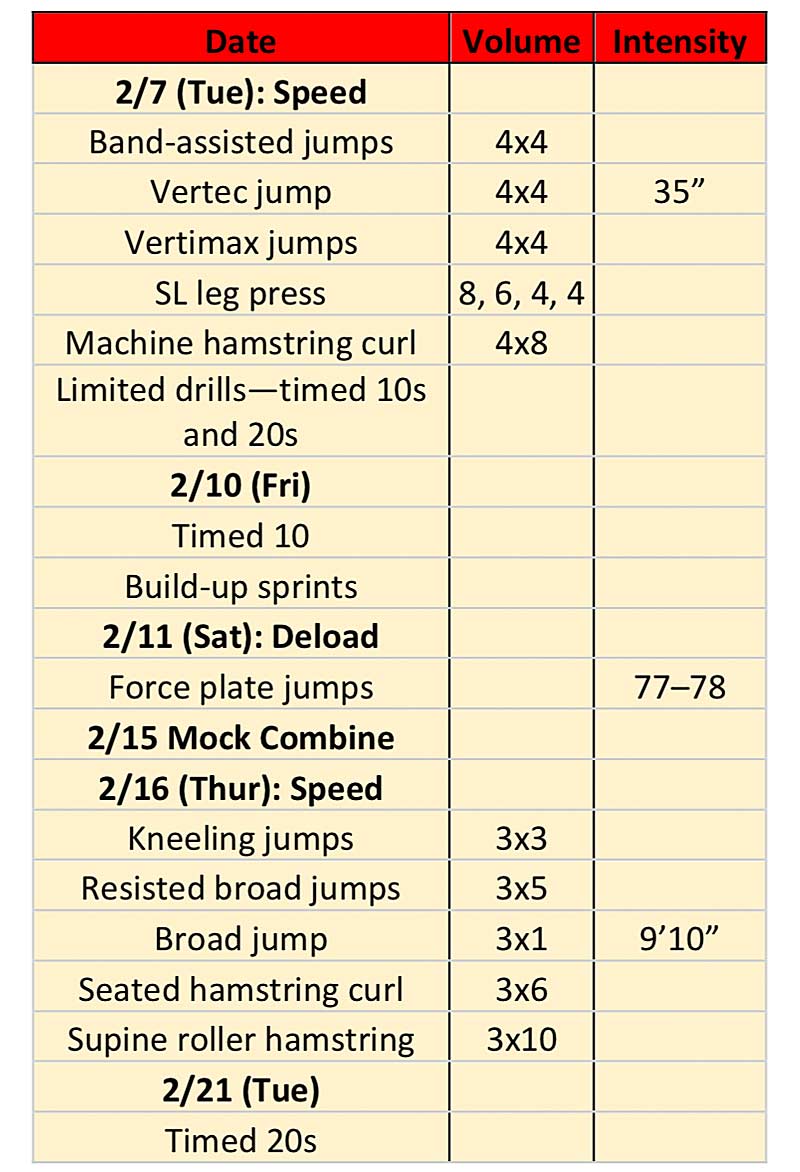

February Training

Once athlete E was back from the Senior Bowl, the focus was on getting him recovered and healthy from the week of intense practices and the game itself. The strength and power established in December and January set a good foundation for the peaking process needed in February. The weight room consisted of more jumps and less squatting, while the speed work consisted of fewer drills, less volume, more rest, and longer distance sprints.

Drop-Off in Performance

Measurable numbers will decline at some point—I have heard the coaches at Spellman Performance refer to this as “the valley”—it pretty much happens to everyone. Training for the NFL Combine is a long, tiring process, and athletes are rarely completely fresh and recovered, so we can’t expect them to break personal records every day. The biggest thing to look for during this time of decreased performance is their technical performance. When watching them run or reviewing film of the athletes running…are they running with the proper technique? If they are and their performance is down, they simply need to recover and for their legs to feel fresh again.

The biggest thing to look for during this time of decreased performance is their technical performance…are they running with the proper technique?, said @steve20haggerty. Share on XDuring training, when they are sprinting four times per week, plus working on agility drills twice a week, doing position work, and lifting four times per week, we expect decreased performance. Needless to say, athlete E was often sore, and his legs never felt great. If they are running technically sound—which to me is being in the proper positions to direct force into the ground in the proper direction—then there shouldn’t be anything to worry about. If his legs are sore as we still push him to improve his physical qualities, such as strength and power, once we begin to taper, that power can be expressed. Athlete E had performance drops at times, as we accepted.

Again, he was training intensely six days per week with multiple workouts per day—this is not ideal for breaking personal records daily. Yet he and all of our athletes want to see faster times every day, which does not always happen. That is a tough part of this process for many guys to understand. As a coach, it is my job to get him to understand that performance will sometimes decrease. When reviewing athlete E’s sprinting film with him, it was easier to show him how much he has improved technically and get him to understand that once he begins to taper, we would see significant time improvements.

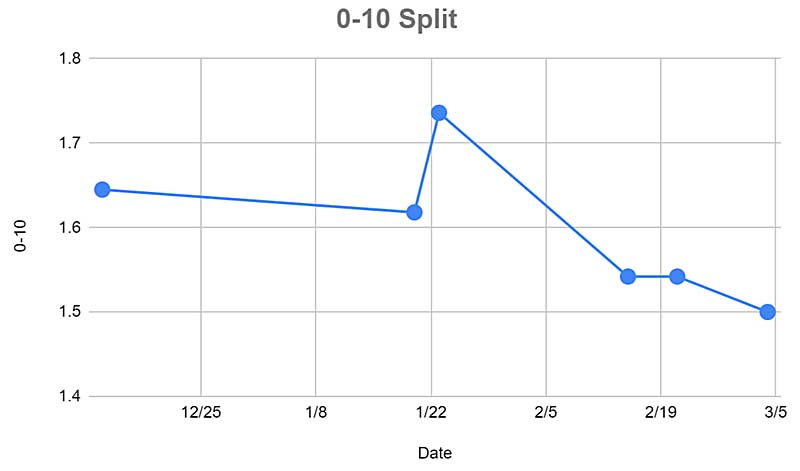

The biggest dips in sprint performance seemed to occur on January 13 and January 23, and the only drop in performance on jumps was on January 10. January 10 was a Tuesday, and January 13 was a Friday of the same week. This was athlete E’s deload week—he had been training hard for a few weeks prior, and it was time to pull back on overall training volume. A deload for athlete E on the field looked like almost no drills on the feet—no sled pushes, A-skips, or anything like that. He did some traditional arm swing drills from a kneeling position and still hit full-speed sprints, but less distance and fewer reps than the rest of his group.

Two things could have occurred here, or maybe even a combination of the two—he was slightly overreached or over-trained, which led to a decrease in performance, and we did a good job of giving him a deload week. Or what I have noticed with deload weeks is that guys tend to relax and let off the gas a bit. Some guys celebrate the deload week because they are constantly sore and want to feel fresh again. Athlete E is the type of guy who always wanted to do more and get extra work, so I don’t know if I saw him pull off the gas much. My guess is he was overreaching, which is a good thing—we want to push the athletes over the edge slightly and in a controlled manner. We want the super-compensation effect that comes with it.

The other date of decreased performance was on January 23 and even a little on January 24. This was a Monday and Tuesday of the week leading to him leaving for the Senior Bowl. Again, a couple of things could be at play here.

- On the previous Friday (January 20), only a few days prior to the decreased sprint times, athlete E had a higher training volume on the field of overspeed sprints and long-distance sprints that he had not completely recovered from. Overspeed sprints are the highest stress we place on the athletes from a central nervous system standpoint. It is very common for guys to feel sluggish the day after these.

- He may also have been feeling some stress and anxiety about the upcoming Senior Bowl. This is a week of intense practices, meetings, and interviews, and really getting in front of scouts and coaches for the first time. Many guys will ask us if they can do extra position work in the week leading up to their All-Star games or even do less in their weight room lifts in an attempt to avoid being sore.

I think it’s important to consider both the physical and mental factors that could lead to improved or decreased performance. My guess for athlete E for this drop in performance is that the overspeed sprints definitely played a factor (many others ran slower sprint times on January 23 and 24, whether they were going to the Senior Bowl or not), but the stress of the upcoming All-Star game may have had an impact as well.

The NFL Combine

I’m not sure how many readers are aware of this, but the 40-yard dash times you see on TV for the Combine are not connected to the laser timing lights on the field. Even when NFL.com publishes “official times,” those are not the times from the timing lights on the field. Why doesn’t the NFL release the actual times, as you see for the Olympic track events? I don’t know the answer.

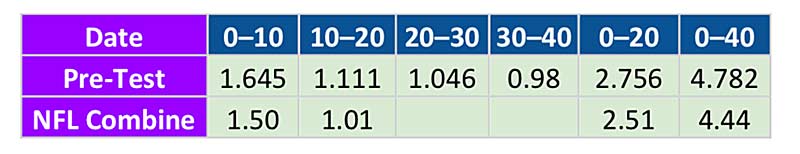

NFL teams receive an Official Combine Report about one week after the Combine concludes. This has the official measurements for all the performance tests, specifically the times for the 10, 20, and 40. I used the times from the Official Combine Report for this article.

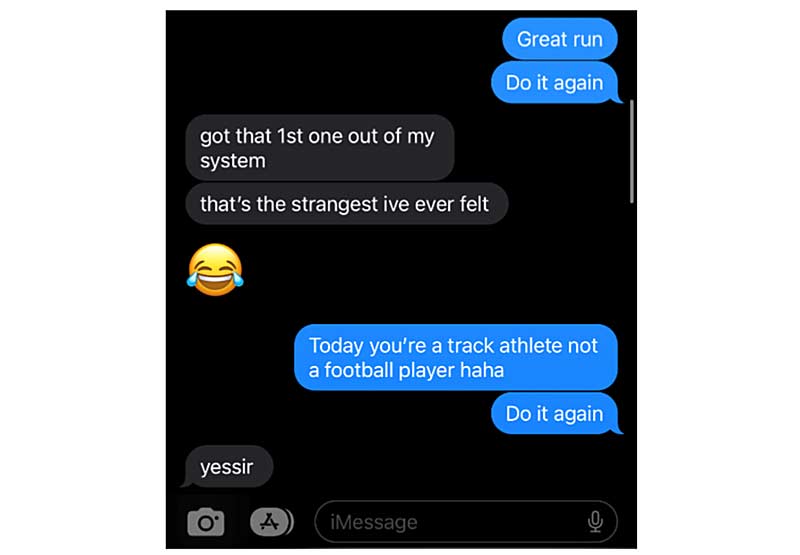

At the Combine, athletes get up to two 40-yard dash sprints with a long rest in between. I was texting athlete E at the time of his first sprint and during this rest as well, trying to keep him focused. Something interesting to note is that he mentioned how strange he felt, referring to sprinting in a dead silent stadium with everyone staring at and evaluating him. These football players are used to loud, intense, and chaotic environments. The Combine is intense, but there is not the same energy as a football game—yes, there is a crowd in one corner of the stadium, but rarely does any cheering occur. There is almost no noise.

He mentioned how strange he felt sprinting in a dead silent stadium with everyone staring at and evaluating him. These football players are used to loud, intense, and chaotic environments. Share on X

Takeaway

My biggest takeaway from the NFL Combine training this year was simply a reminder of the performance drop-offs that occur. As long as the technical mechanics of the sprint are improving, the power outputs in the weight room are improving, and you have the ability to assess the need for a deload week or much-needed recovery, there is nothing to worry about. This is all part of the process. Athlete E was able not only to hit all of the target numbers we looked at for the 40, broad jump, and vertical jump but surpass our goals.

Lead photo by Zach Bolinger/Icon Sportswire

Since you’re here…

…we have a small favor to ask. More people are reading SimpliFaster than ever, and each week we bring you compelling content from coaches, sport scientists, and physiotherapists who are devoted to building better athletes. Please take a moment to share the articles on social media, engage the authors with questions and comments below, and link to articles when appropriate if you have a blog or participate on forums of related topics. — SF

Great content Steve! A few comments/questions for you:

A statement that stood out while reading this: (Speaking on both the speed and lifting sessions) “Our goal was to raise the muscle’s capacity to produce force and the nervous system’s ability to produce force quickly and then apply it in the fashion in which he would be tested”. Simple, straight forward objective that 1. makes sense to the athlete and 2. obviously worked. Keep it simple.

How do elite athletes respond to drills that might seem “basic” (my main thought being arm swing drills, etc.). Do you guys ever get any push back or do they trust the results they’ve seen/heard about?

Lastly, what do you guys use to measure bar velocity?

These numbers are awesome. Great work and fantastic summary!

Hey Alex! Thank you for the comment and the questions.

The guys were not fans of doing the arm swinging drills. It wasn’t that they thought it was too basic or useless, but instead that it is just fatiguing. With all of the lower level drills that we implemented I can’t think of a time when I received any pushback (except the warm up, no one likes to warm up).

To track bar speed we use the PUSH system. We have used the Tendo in the past, but the PUSH is more affordable for the amount we need.

Hi Steve

I notice in the training you guys did not use any heavy squats such as 1rep max ,and also with speed squats with bands how much bar weight was use and band weight you guys used. Did you a box for the squats Thanks