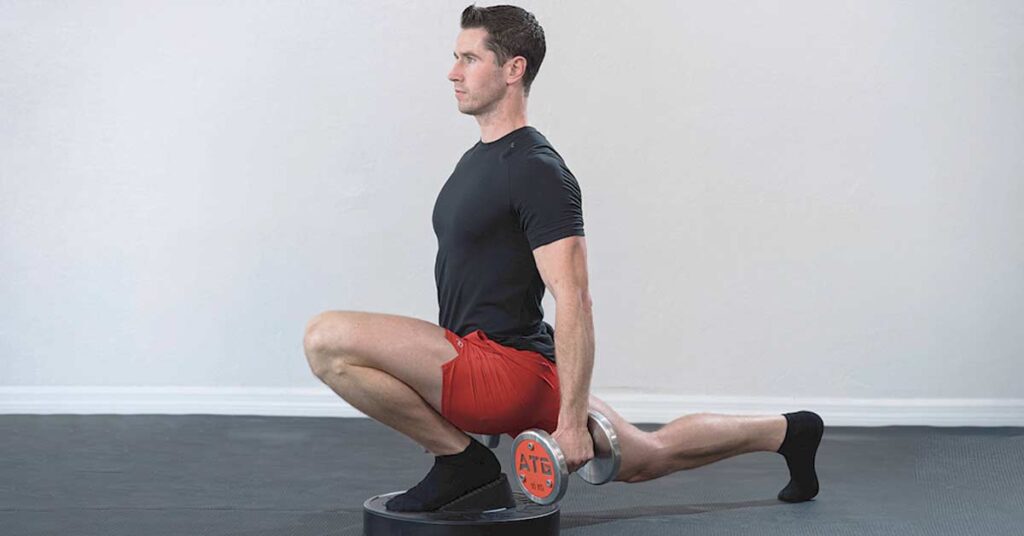

In the summer of 2016, videos began circulating of James Harrison out in the Arizona heat playing a grueling game of what looked like sand volleyball. The twist was that the four NFL players on the court weren’t bumping, setting, and passing a normal volleyball back and forth—they were catching and hurling a 12-pound medicine ball over the net. The game was called “Danney Ball” after its creator (and Harrison’s strength coach), Ian Danney.

James Harrison, the Super Bowl Champion and All-Pro linebacker, was gaining a great deal of attention in the off-season for his freakish feats of strength. Not only was the Danney Ball video circulating, but so were videos of Harrison doing 1,800-pound sled pushes, repping out 400-pound earthquake bar squats and 300-pound Duffalo bar bench presses, and making light work of hanging band technique Z presses. In the background of all these training videos was Ian Danney.

Make no mistake: the demonstrations of physical strength displayed by Harrison are incredibly impressive, but the insane amounts of weight being moved in the training videos weren’t what piqued my interest. I kept coming back to the game of Danney Ball, knowing there was something special there that I could use with my guys.

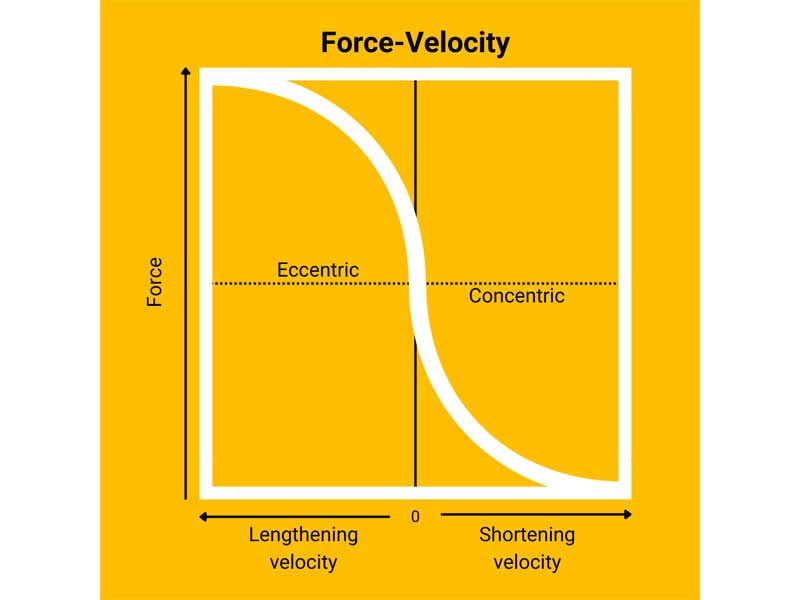

With Danney Ball, Ian Danney came up with one of the most competitive ways to surf the load-velocity curve using light loads in an intent-driven manner, says @CoachAlanBishop. Share on XThe load-velocity curve is an inverse relationship between the relative load (weight) used in an exercise and the effect that load has on the velocity (speed) of the exercise. A well-designed training program should, in the words of renowned strength coach Ben Prentiss, “surf the curve.” This means there should be time spent with heavy loads moving slow, light loads moving fast, and everything in-between. Competition and small-sided games have a unique way of positively influencing training intent, and in my opinion, Danney came up with one of the most competitive ways to surf the curve using light loads in an intent-driven manner.

The focus of this article is not to dive into the merits of med ball training, provide the latest training plans to surf the load-velocity curve, or debate weightlifting versus throws. My goal here is to recognize Ian Danney for his unique training method and provide a blueprint for other coaches to see how I’ve implemented the game with the athletes I train at the University of Houston.

Evolution of Danney Ball: Houston Basketball Style

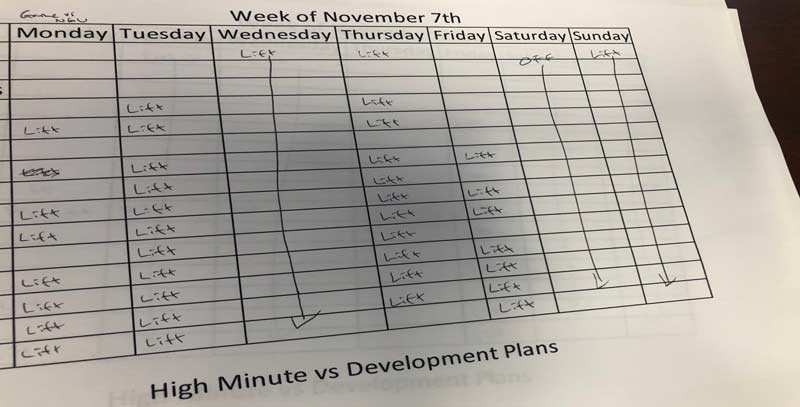

The NCAA permits Division 1 Men’s Basketball an eight-week summer calendar of off-season training. At the University of Houston, we follow the summer school academic calendar to get these eight weeks of training in. We split this time into four weeks of training in June and four weeks of training in July. I utilize these weeks for training dedicated to general physical preparation and the saturation of many physical attributes. We only have 32 training sessions during these eight weeks, and I don’t believe in wasting valuable days with nonsense training. These 32 sessions are pragmatically structured to try and elicit the greatest adaptations possible.

Danney Ball becomes an effective outlet to mix it up and have some fun but still get in a meaningful day of training, says @CoachAlanBishop. Share on XThat said, however, none of our players are here on a weightlifting scholarship. Make no mistake about it, we have a great training culture, and our guys work their butts off in the weight room. But they are there to play ball, and sometimes it’s nice to get out of the building for a change of scenery. This is where Danney Ball becomes an effective outlet to mix it up and have some fun but still get in a meaningful day of training.

Video 1. Danney Ball 2023, University of Houston Basketball.

What You Need and How to Play

Getting started is relatively easy. Here’s what you need to know.

Medicine Ball

I’ve used both heavier and lighter balls, but I’ve come to the conclusion that 12-pound medicine balls work best with my players.

Playing Surface

We play the game on a sand volleyball court. I’m a big believer in the potential benefits of sand pit training for the foot and ankle, but for the sake of this article, I won’t get into that. Inevitably, a game of Danney Ball turns on a strategy of making your opponents sprint all over the court to wear them out. When played on sand, you’ll see far more effort in sprinting and selling out to catch the ball.

No player wants to land face first on a wooden court diving for a med ball, and no coach wants to lose their job because the starting point guard fractured their wrist diving on wood to catch a med ball in the off-season. For the most competitive and safe games possible, play on sand.

Teams

Each team consists of two players. In a perfect world, one of those players is an upperclassman, and the other is an underclassman. In an even more perfect world, one of those players is a guard, and the other is a big.

I’ve seen videos posted of other coaches playing different variations of med ball volleyball with up to six kids on each team, but this ultimately defeats the purpose of the game. Having more than two players on each team shrinks the surface covered by each player during the game and reduces the number of throws each player executes. I won’t budge on this—no more than two players per team.

Having more than two players on a Danney Ball team ultimately defeats the purpose of the game, shrinking the surface covered by each player and reducing their number of throws, says @CoachAlanBishop. Share on X

Scoring

Each game is played to three points, “Rally Style.” This means a point is awarded every possession, keeping the speed of the games moving fast and making each throw/catch more meaningful. Once all games are played, we play a championship bracket with the championship game being played to five points.

Games

Teams compete in a round-robin tournament, with each team facing every other team one time. Once a team scores three points, they get the win. After all the round-robin games are played, the four teams with the best records play in a single elimination Final 4.

Round-robin schedule generators can be found online with a quick Google search.

Rules

Each serve is a backward underhand throw from outside the line.

After the initial serve, the ball is caught and immediately thrown back over the net. There is no passing to teammates. Whoever catches the ball must immediately stop where they catch it and throw the ball back over the net.

This is where some subjectivity comes into play. My rule is that players must make a best effort to stop immediately after the catch and immediately return the throw from where the ball was caught. This can get a little tricky as players start sprinting around the court—sometimes momentum carries them into an extra step after the catch. But as long as they make a legitimate effort to stop all momentum immediately and return the throw immediately, they’re fine.

An important nuance to emphasize before the game starts is that “out of bounds” for Danney Ball is based on volleyball rules, not basketball rules. In basketball, the ball is dead when a player or the ball touches the line. In volleyball, the ball is still considered “in” if it touches the line, AND players can touch the ball when they are outside the lines. This means players might catch the ball inbounds, but momentum carries them a step over the line—in this case, the ball is still live and can be returned. If a ball is thrown over the net and hits the line, the throwing team gets the point.

Like the key rules with any small-sided game, if these out-of-bounds rules aren’t established prior to the start of tournament play, you’ve set yourself up to listen to everyone argue for the next 10 minutes. ESTABLISH THESE RULES BEFORE THE GAME STARTS.

Video 2. Danney Ball 2023, University of Houston Basketball.

Shout-Out to History: Hoover Ball

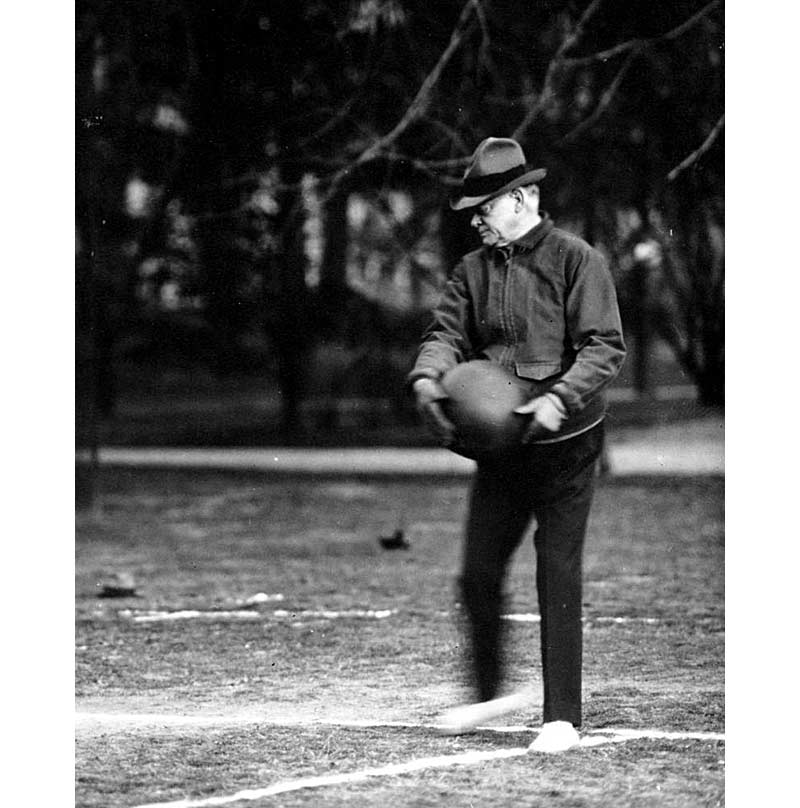

Even though this article is meant to provide clarity on how to execute Danney Ball in a team setting, it is fitting to include a shout-out to President Hoover and his physician, Joel T. Boone.

In 1928, Hoover and Boone were returning from a trip to South Africa aboard the battleship Utah when they witnessed the sailors exercising with a game of “bull in the ring” using a medicine ball. I’m not an expert in the rules of 1920s naval exercise games, but the gist of it was that the sailor in the middle of the ring tried to intercept the ball being passed by the sailors on the outside. This game led to the creation of “Hoover Ball.”

Hoover Ball was played on the White House lawn from 7:00–7:30 a.m. Monday thru Saturday, using a 6-pound medicine ball and an 8-foot net in a game with rules that have been described as a hybrid of volleyball and tennis. Teams consisted of 2–4 players. This was President Hoover’s preferred method of exercise, and by all accounts, he was extremely dedicated to his daily workout routine of 30 minutes of rigorous Hoover Ball.

I think it is fitting that this little bit of training history be included in the article to give credit to Hoover and Boone for their innovative approach to exercise. Including it also helps clarify that there are some subtle differences in how the games are played, which brings me to an important point. Whenever I post photos or videos of our guys throwing med balls on a sand volleyball court, the comments are always a combination of “young” coaches praising the game of Danney Ball and “old” coaches praising the game of Hoover Ball.

Whether you call it Danney Ball or Hoover Ball, the important thing is getting a great training session in, says @CoachAlanBishop. Share on XI learned about the game from videos of James Harrison being coached by Ian Danney, so I call it Danney Ball. If you learned it from the Hoover archives and call it Hoover Ball, more power to you. The important thing is getting a great training session in, whatever you call it.

Since you’re here…

…we have a small favor to ask. More people are reading SimpliFaster than ever, and each week we bring you compelling content from coaches, sport scientists, and physiotherapists who are devoted to building better athletes. Please take a moment to share the articles on social media, engage the authors with questions and comments below, and link to articles when appropriate if you have a blog or participate on forums of related topics. — SF