[mashshare]

I was lucky enough to meet Boris Sheiko in June of 2015. I was the head coach and Director of Strength and Conditioning at the gym where he presented his first seminar in the US. At the time, I didn’t know much about Boris or his coaching, just that he had coached many successful lifters in Russia, and I had seen his templates that were available on the internet.

After hours of listening to him speak and watching him coach, I was intrigued. Everything that he said made so much sense to me. I was just starting my journey into powerlifting, and I had my first meet coming up in October of the same year.

I’ve been competitive in everything that I’ve done in my life, and I wanted powerlifting to be the same. I was starting the sport later in life but still had some long-term goals laid out. I discussed these long-term goals with Boris and hired him as my coach. Little did I know the impact that decision would have on my coaching career. Over the next three years, I worked with Boris and ran his program as well as asked him many questions. This experience laid the foundation for my powerlifting club, Precision Powerlifting Systems.

Lifting as a Skill

For Boris, technique is the most important aspect of training; the Eastern European countries treat the lifts as skill development. Their major focus is neuromuscular coordination. A sticking point is not always due to weak muscles, it may be due to poor skill or neuromuscular coordination by the lifter.

Eastern Europeans treat lifts as skill development, focusing on neuromuscular coordination. Share on XWe want each repetition in training to look the same, which is how we build a stable movement pattern. If we do five repetitions that all look different, we’ve trained five different movement patterns. This type of training builds an unstable movement pattern that cannot be stressed maximally because it’s already broken. Increasing the skill level of performing the lifts requires practicing the lifts. Twenty percent of the total volume comes from the competition lifts themselves, 60% comes from what Boris calls his “special exercises,” and 20% from GPP.

The special exercises are variations of the competition lifts selected to fix technical errors—these variations are done with competition foot placement, bar placement, grip, and deadlift stance. The similarities to the competition lifts allow the athlete to carry over the skills practiced within the special exercises. The more similar the forces, angles, and speeds of the lifts, the more carry we get. This is the law of specificity.

Intensities and Volumes in the Sheiko System

The average intensity of the lifts is 70% of 1RM, plus or minus 2%, for all repetitions taken at 50% or higher. An existing body of Russian research indicates that anything under 50% does not increase muscle mass or strength.

Most of the sets have 3-6 repetitions. According to research, it’s not so much the number of reps we do, but the total volume. Also, research shows that strength is best achieved within the 3-6 rep range with 1-4 reps in reserve (RIR). This combination helps us build both muscle mass and strength.

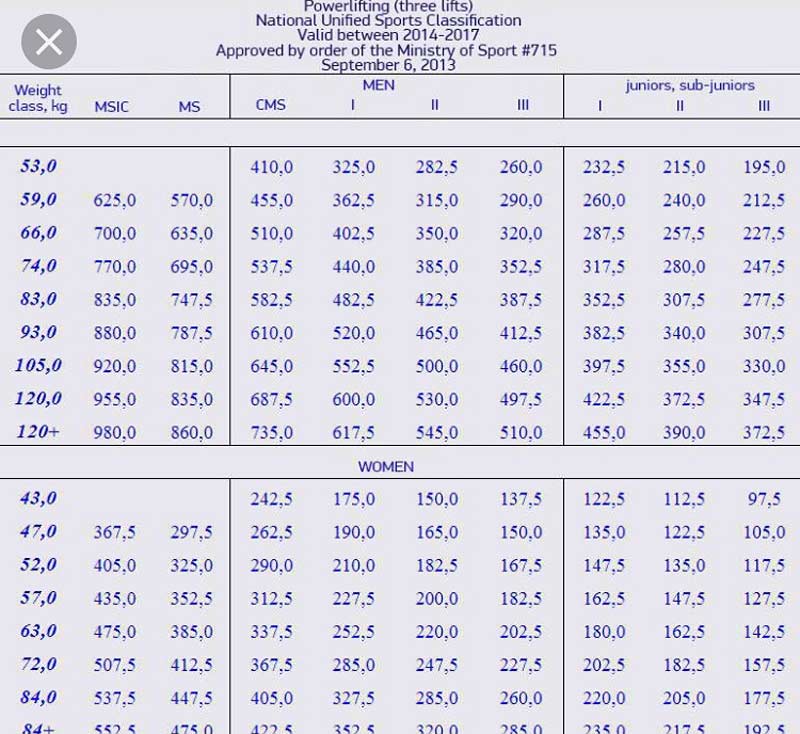

For beginner lifters, the average intensity will be slightly lower. There will be many repetitions of the lifts taken between 70% and 80% of 1RM to work on technique. The number of lifts is based on recommendations that coincide with the lifter’s classification within the Russian Classification Chart.

The chart categorizes lifters based on total, gender, and body weight. As the lifter grows within this chart, their total number of lifts grows with them, which ensures their long-term success. The chart allows the lifters to improve over time and keeps their current volumes in check. Increasing volumes too quickly can lead to a career cut short by peaking too early or by increasing injury risk.

Load Management in a Sheiko Program

Load variability may be the most important aspect of programming in this system. I’ve taken this to heart and made it the foundation for our team programming. Load variability includes changing exercises, reps, and intensities. It also refers to alternating high, medium, and low-stress training days to keep the athlete progressing steadily while also keeping down the risk of injury. We never want to stray too far from baseline, either up or down.

Load variability may be the most important programming aspect of the Sheiko powerlifting system. Share on XI have found this to be true in my program over the past three years. The average weekly volume was always very close to my baseline. There were higher load, medium load, and low load weeks, but none of them got too far away from the baseline.

This is where the Acute: Chronic Work Ratio (ACWR) comes into play in my programming for my lifters. The ACWR is a tool for monitoring training loads that’s been primarily researched in a team sport setting, not powerlifting.

In the model that I use, the chronic workload is a running 4-week average of the athlete’s training volume. The acute workload is this current week’s training volume. We want the ratio of the acute workload and the chronic workload to be between 0.80-1.30 and 1.0 of the lifter’s baseline. This ensures we don’t get too low below baseline or too far above.

It also gives us a guideline for how quickly we can increase training loads. Increasing them too quickly comes with a risk, as does getting too far below the baseline. Doing too little does not leave the athlete prepared to handle larger loads.

In the research, there are internal and external factors that impact the ratio. External factors in powerlifting are the actual loads lifted in training. The internal factors are lifter’s feelings and effort. Upon entering the gym, the lifter rates how they feel on a 5-point scale:

- Fatigued

- Slightly fatigued

- Normal

- Slightly excited

- Excited

They also record the RPE for the last set of each competition lift or variation as follows:

- RPE 10—Maximal effort, no more reps left

- RPE 9.5—Could not do 1 more rep but could add weight

- RPE 9—Definitely could do 1 more rep

- RPE 8.5—Maybe could do 2 more reps

- RPE 8—Definitely could do 2 more reps

- RPE 7.5—Maybe could do 3 more reps

- RPE 7—Definitely could do 3 more reps

- RPE 6.5—Maybe could do 4 more reps

- RPE 6—Definitely could do 4 more reps

We don’t want the rating to be any lower than an RPE 6 or greater than an RPE 9. This way, technique stays consistent and the athlete can recover. Unlike in the research, I separate the external and internal load monitoring. This allows me to determine whether there’s an external load issue or an internal load issue when things are not going well. It also allows me to identify when I need to drop the external loads or when I can increase them.

Cultural Differences in Training Lifts

There are some important differences with my athletes compared to those in Russia—in Russia, athletes are raised with the sport. Athletes pursuing the discipline can attend a school that offers powerlifting, just like a college offers a major. By the time many lifters are 20 years old, they’ve been lifting for ten years or so. In contrast, this is the age when most Americans are starting their powerlifting careers.

We need to make some changes to the model to adapt it to our culture. No one will want to work on technique for ten years before starting to load it more. And because many lifters here start training at a later age, it’s harder to master the skill.

The Eastern Europeans also go through many years of GPP work to prepare for the high volume powerlifting programs they do later on. This strategy is also lost on American lifters. We need to find a way to get strong at many different angles to build a resilient athlete.

How to Modify the Sheiko System to Train American Powerlifters

The tweaks I’ve made to the program are in exercise selection; if a lifter has good technique in the lifts, we’ll vary the exercises a bit more than what I saw in my program with Sheiko. I’ll use different bar placements and foot placements on the squat, different grips and no-arch with the bench press, and opposite stance and different foot placements on the deadlift. We only do this when the lifter has demonstrated a good technique that holds up under heavier loads.

We've tweaked the Sheiko system to adapt to American powerlifting culture and training. Share on XIf the lifter still needs technical work, the variations will be very similar to the competition lifts until their skill level improves. Once we build technical proficiency, we want to build well-rounded athletes. They should be strong at the high bar and low bar, wide stance and close stance, all grips, and all deadlift stances. If we discover a weakness, we’ll continue to push that variation until it becomes a strength. This strategy is very different than what I did under Sheiko.

No matter the exercise selection, however, we follow the recommended volumes, number of lifts, and average intensities laid out by Sheiko. We still follow the belief that the technique is the most important aspect of training. We also keep volumes close to the baseline and alternate high, medium, and low load days to keep the athlete progressing forward while keeping them as healthy as possible.

Since you’re here…

…we have a small favor to ask. More people are reading SimpliFaster than ever, and each week we bring you compelling content from coaches, sport scientists, and physiotherapists who are devoted to building better athletes. Please take a moment to share the articles on social media, engage the authors with questions and comments below, and link to articles when appropriate if you have a blog or participate on forums of related topics. — SF

[mashshare]