I’m sure all of you have gone through this before: Training sessions have been going as planned, and your squad is getting faster, stronger, and more explosive. Then, one day you walk in to greet your athletes and get the “So, this happened at practice…” scenario. A sprained ankle from going too hard during a small-sided game, beat-up shoulders from too many balls thrown or laps swam, or exhaustion from enduring the dreaded “extra conditioning” for disciplinary action.

Most of us understand in today’s multi-/year-round sport landscape, our plans and programs are at the mercy of any repercussions from practices and competitions. Share on XMost of us understand in today’s multi-/year-round sport landscape, our plans and programs are at the mercy of any repercussions from practices and competitions. If you work with developmental athletes, you can also add in the compounding kids will do stupid stuff and hurt themselves factor and then quickly learn what agile periodization looks like!

If you’re fortunate enough to get feedback from your coach on a regular basis, then planning for these instances will be a tad easier. You can now think ahead to adjustments you can make for lower body training on “flipper day” if you happen to get a handful of swimmers with sudden foot, knee, and ankle issues. If you find yourself having to negotiate an extensive “DON’T” list from ATCs, PTs, or the doctor, then you may have your work cut out for you.

In either case, you don’t have to let your squad succumb to getting “doctored” out of training. I get it: Pain is an inhibitor of movement, and a true injury is debilitating. But if they were still able to step foot into the room, then they still ought to do something effective. As coaches and facilitators of their success, we must never allow our kids to gravitate toward ease and shy away from the work.

Remember in the movie 300 when Dilios patched his eye?

King Leonidas: “Dilios, I trust that ‘scratch’ hasn’t made you useless.”

Dilios: “Hardly, my lord, it’s just an eye. The gods saw fit to grace me with a spare.”

An extreme example, I know—but are initiative, obligation, and effort not foundations of a formidable culture? Do we not want our athletes to learn about the value of finding ways to succeed despite setbacks? Or about upholding their commitment to the team and themselves? This can be a deeper discussion in and of itself, but I digress.

[adsanity align=’aligncenter’ id=9053]

Let’s also distinguish the scenario of injury versus acute restriction. As stated above, an injury would be physical damage to the body that prevents someone from performing a task. As we know, this can and DOES happen in practice and play. In this case, you most likely will receive communication of the incident, and the athlete may or may not be at the session. If you receive an athlete who is reporting the injury to you, it is your LEGAL, ETHICAL, and MORAL obligation to send them to the ATC office or require an outsourced appointment to a qualified physician for a diagnosis.

For those athletes not in this category but reporting an ache, pain, nick, or ding, we can consider them as having an acute restriction. Sound and legal practice calls for us to listen to the athlete about the issue and make the necessary change. In no way are we to apply any other type of intervention! So, without burdening yourself with the idea of, “what the hell do I do now?” I’ll explain how you can still deliver the goods to the athlete and not have to sacrifice the integrity of the program.

What We Can Progress, We Can Also Regress

Most of you are familiar with systems of progression and regression that may be based on these factors:

- Skill level—Does this athlete consistently perform the basic pattern in a flawless manner? If so, in what way can we challenge them further?

- Strength level—Has this exercise run its course with this athlete? Is it no longer driving progress?

- Readiness—Does it look right; does it fly right? If not, is this athlete ready for this today?

Data collection, the coach’s eye, and communicating with your athletes can all help you answer these questions. From there, having a system in place helps to rectify the problems.

Coach Ashley Jones developed a system based on the statistical concept of the bell curve. The mean exercise (middle of the curve) represented the lift/exercise “middle” that the majority of his athletes could do at the time. Progressions and regressions of the exercise are represented by standard deviations of +/-1 or 2 based on the movement pattern.

For example, if the barbell deadlift is the mean exercise, regressions can include a trap bar DL and RDL (-1/-2, respectively), and progressions may include power clean and power snatch (+1/+2, respectively). Essentially, individualization of training can be administered without sacrificing the integrity of the program. Coaches can use the tools above, tempered by the experienced coach’s eye, to keep their athletes moving forward even if it means taking a temporary step or two back.

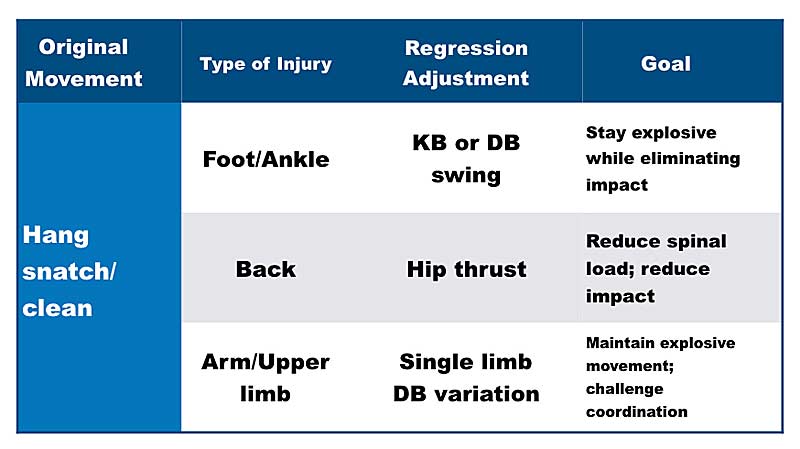

For coaches who have dealt with the M*A*S*H unit scenario, I understand how injuries can become a wrench in your day’s plan. Conceptually, we can borrow from Coach Jones’s system above to regress movements based on nicks, dings, and restrictions that day. I’ll list some examples I have encountered over the years, along with the reasons why. By no means is this an exhaustive or comprehensive list, but it does represent real-world adjustments I’ve had to make over the years.

Hinge-Based Movements

Given that Olympic lift variations involve an impact with the floor and more overall movement about the ankle, the kettlebell or dumbbell swing can serve as an ample replacement. Keeping the hips high (as in the high hang position) in this movement resembles a pure hinge, which reduces dorsiflexion of the ankle on the descent. The athletes with the ankle sprains or sore calf/Achilles can also preserve dynamic intent without the cost of impact.

If the back (lumbar) is irritated, then unloading this force becomes the call of the day. I have found that the classic hip thrust (loaded across hips) allows athletes to work through most back issues. Even though the dynamic nature of the movement may be compromised a bit, an explosive concentric action will mostly preserve the intent. This will allow those swimmers who had a heavy fly set to train around the issue for the time being.

I have found that the classic hip thrust (loaded across the hips) allows athletes to work through most back issues. Share on XFor your kids who have a “Don’t do anything with the arm” note from their doctor/ATC, fear not! Have them grab a dumbbell, and they can snatch and clean away (maybe even swing), for the gods were good enough to bless them with another! Mechanical loading may not be the same as a barbell, but the coordination challenge from this upper unilateral variation will be worth the sacrifice. As Bosch may suggest, the novelty of this new pattern will also serve as a bit of an overload.

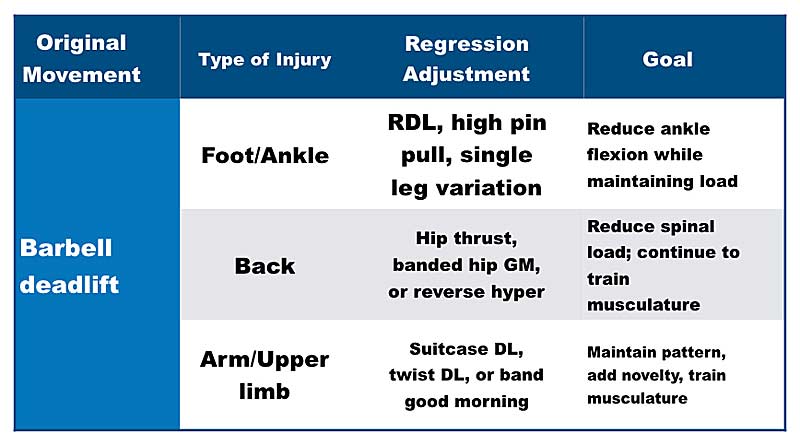

Deadlift-Based Movements

Video 1. Suitcase-style deadlift (SCDL) for athletes with an acute restriction in a single shoulder or arm.

Depending on the severity of the ankle restriction, we can again limit dorsiflexion by utilizing a more hinge-based deadlift from a knee-high pin or RDL variation. For your field athletes who may have suffered a slight tweak or endured many COD contacts at practice, this will reduce flexion of the ankle while maintaining loading. Even though a pin deadlift will allow for more loading, I suggest you stay with what is planned or even lighter.

For your field or court sport athletes with the “Don’t do ___” notes, we can use a single leg variation (on the good leg) with a single dumbbell in one hand, one dumbbell in each hand, or a barbell. In this case, novelty will create the coordination overload in place of mechanical load.

For our kids with sore backs, the replacements for the clean will suffice. We can also eliminate load altogether and perform the reverse hyper/hip extension using a dedicated machine (if you have it) or over a glute ham or an angled bench. For this case, we can still train the musculature given comfort tolerance, which is also a regression we can make if they are fried from a hard practice or contest.

For our one-armed bandits, using the good one allows us to continue training and adds novelty. We can employ the suitcase-style deadlift to offer a challenge to the trunk and proprioceptive work. The SCDL can be done with a kettlebell, dumbbell, or barbell. For more advanced movers, we can add a rotational component via the “twist deadlift.”

Video 2. The twist deadlift is best performed with a kettlebell, and this variation calls for a load to be place on the outside of the foot next to the pinky toe. From here, the athlete hinges (as in a normal deadlift) and reaches for the bell with the opposite hand by rotating axially. Maintain tension in the hamstrings before ascending to the standing position.

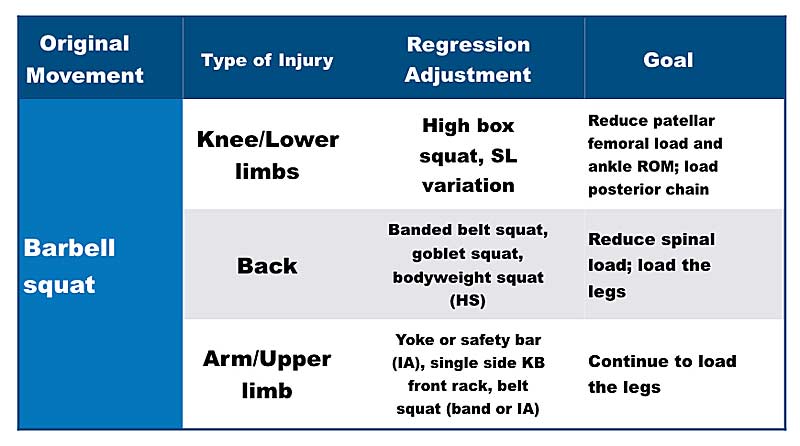

Squat-Based Movements

I’ve experienced a slightly different injury set with this one, mostly regarding the knee.

If an injury to the lower limb or knee still allows some weight bearing—but limited movement—we can apply the high box squat, focusing on keeping a vertical shin. For what we may lose in transfer, we will gain in loading the hips and adductors. This is a great alternative for those in this bucket: Keep loading 5–10% lighter or simply have them work with the load the limb can tolerate.

If the restriction is severe enough that it doesn’t allow bilateral load, then a single leg variation will become necessary. Be wary here, as hooking the bad leg on a bench or support with an achy knee may aggravate it. The “pistol” style squat or rear foot suspended single leg squat will have to do.

If the ankle isn’t having it, then certainly DON’T use the classic split squat or lunge, as the rear leg ankle will be under increased stress. You can add the RFESS to the arsenal above. Even though load and force may be compromised, the novelty of stimulus will serve these athletes well as they heal. Your football lineman and flipper-day swimmers will appreciate this adjustment!

Video 3. How to cinch and adjust the bands and perform banded squat movements.

If the back is a limiting factor, we can load the legs via a leg press or belt squat machine (if available). If we aren’t fortunate to have those options, we can use the goblet squat with a kettlebell or dumbbell or rig a belt squat with a dip belt or bands. The classic belt squat will allow us to preserve load, and using bands we can work explosively, while preserving the back. To eliminate external load altogether, we can apply the bodyweight squat or use the support of the hands to further deload the system. This isn’t the most ideal situation, but “intensity” can be preserved using higher reps, tempos, isometric holds, and so on.

This squat adjustment uses the Hatfield/safety yoke squat bar—a tremendous tool that allows for all the benefits of normal squatting without the shoulder stress of holding a barbell. Share on XFor our one-armed bandits, our squat adjustments call for using the Hatfield/safety yoke squat bar if we have one. This tremendous tool allows for all the benefits of normal squatting without the shoulder stress of holding a barbell. If we don’t have this tool at our disposal, we can use the belt squat example above without any compromises. If kettlebells are available, hold one with the good arm in the front rack. What we give up in loading with this variation, we gain in novelty with the offset load.

Upper Body

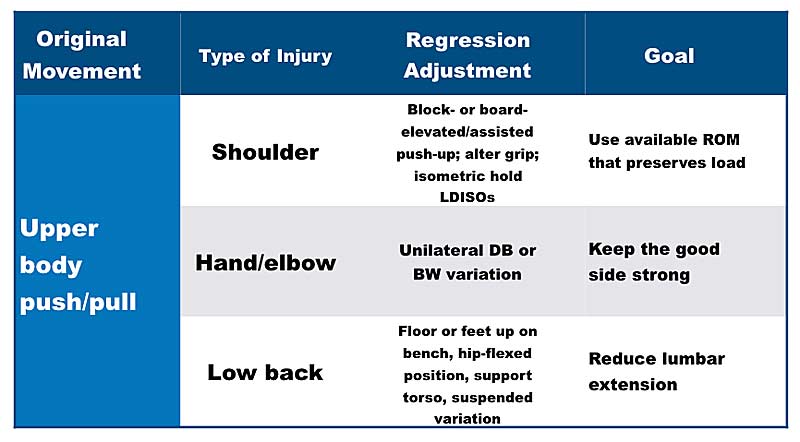

Our final category will encompass the entire upper body. Most of the adjustments will be universal for push and pull exercises, along with some issues you may have not thought of.

I’m not one of these “anti-overhead” coaches who is fearful that my athlete’s shoulders will explode if they train presses; in fact, I truly believe it’s the other way around. But I do find it good practice to avoid vertical pushing and pulling if shoulder issues arise. For that reason, the adjustments will refer to horizontal pushes and pulls.

Reducing full range of motion in a horizontal push (or pull) will do wonders for limiting compromised ROM and keeping the intensity as intended. For our front seven who are in season or have had a tough day of “inside run,” we can go to the board press for our press work. We can also use a board to limit the ROM for those doing push-ups that day. Further unloading for the push-up can be accomplished by elevating the push surface or using a supportive apparatus, such as a band rigged across a rack. This will fit for athletes “bridging the gap” in a return to play scenario or foundational athletes beginning their training. A veteran squad should be familiar with the regression.

Altering the grip of overhead throwers to palm-facing is not the panacea that some make it out to be and will only work as well as they can anchor their scapula. Share on XFor our overhead throwers (baseball, volleyball, quarterbacks, tennis), we can alter their grip to palm-facing (neutral grip) via a specialized bar or dumbbells. Be warned, though—this is not the panacea that some make it out to be and will only work as well as they can anchor their scapula. If the shoulders are shrugged up and their elbows are winging, then somehow you need to teach them better technique. Swimmers in the shoulder M*A*S*H unit may use a long-duration isometric (LDISO) row to allow for a low-cost but effective stimulus that aids in posture development. Use 15- to 30-second holds in the TRX, cable, or band row in the uncompromised range.

For the swimmer who endured a voluminous pull set, a tennis player with a cranky elbow, or the baseball catcher with a beat-up hand, the simple solution is we go full one-armed bandit. Just about any single arm push or pull variation will fit, sans those one arm rows where you use your off hand to support posture. In this case, use the classic “Pass Pro” two-point stance, anchoring the forearm to the thigh, or use a cable or band. Given most programs use pulling exercises as “grinding style” for moderate-to-high rep ranges, we will not lose much regressing to a cable or band.

Adjusting exercises for a sore back is typically ignored, but any time we can mitigate lumbar extension we should consider it. They may be able to press vertically by getting in a half kneel or seated position (on the floor). Loads will lighten but will help mitigate lumbar extension as in a standing press. For horizontal presses, we can regress to floor presses or have them put their feet up on the bench. Load may be compromised, but it’s worth the trade-off minimizing hip/lumbar extension.

Externally loaded horizontal pulls are best done in chest-supported fashion by lying prone on a flat bench, eliminating the use of the spinal erectors by placing the bulk of the stress on the posterior shoulder girdle. For vertical pulls, we can either anchor the hips down on a standard lat pull-down machine or, when doing chin-ups/pull-ups, have them support their legs in front of them (with 90-degree hip flexion) on a bar if you have a rack setup or with a teammate.

Making adjustments in every facet of life comes down to what’s “available.” In this case, “availability” relies on:

- Most importantly, current movement/loading restrictions based on aches, pains, or injuries from practice or competition.

- Secondly, the equipment you have available to render those adjustments.

After all, is it not our job to help prepare and prime these athletes for practice and play? Two important aspects of making training adjustments (based on pain or injury) are that it allows for the maintenance of a baseline level of preparedness and it allows for a systemic unloading. Pain is a signal that maybe we do need to pump the brakes a bit. In a way it’s good—if we’re hurt or aching, now we can rest, recover, and come back stronger when called upon.

[adsanity align=’aligncenter’ id=9082]

When Is It Time to Return to Normal?

This determination will be influenced by a range of factors, which (I hate to break it to you) will not be entirely up to us to decide but will be up to us to execute properly. Primarily, from a liability standpoint, we are at the mercy of clearance from a physician, PT, and/or training staff. Even for the acute restrictions, we are legally bound to follow the guidance of doctors and medical support staff. Whether we’re in the private sector or an academic setting, it behooves us to have good working relationships with these professionals, even if that simply means being available for a phone call consultation.

A range of factors determine when it is time for an athlete to return to normal. While it is not entirely up to us to decide, it is up to us to execute properly. Share on XOnce clearance is given, we must assess:

- How much time we have remaining to effect positive improvement. If our time with an athlete is not year-round, we will have more time to reintegrate our M*A*S*H units earlier in a training season. If we only have a few weeks left, we honestly can’t expect to influence much—still, providing them a remnant of where they once were may be good for their soul and future progress.

- The spirit of the athlete. This is a perfect opportunity for us to give our athletes “ownership” of their training. I prefer to give them a goal exercise to execute before they can return to their standard program—this way, they can approach the task with urgency or patience, regaining confidence at their own pace.

By no means is this an exhaustive list, nor are the regressions written in stone, but it should give you some pragmatic ideas and sound reasoning for adjusting your program on the fly. I can insert the classic cliché here, if you fail to plan, you plan to fail…but in all honesty, even our best-laid plans need “liquidity” to make slight or more drastic adjustments based on what’s available.

Since you’re here…

…we have a small favor to ask. More people are reading SimpliFaster than ever, and each week we bring you compelling content from coaches, sport scientists, and physiotherapists who are devoted to building better athletes. Please take a moment to share the articles on social media, engage the authors with questions and comments below, and link to articles when appropriate if you have a blog or participate on forums of related topics. — SF